About Fernando Botero

“I am the most Columbian of the Columbian artists.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fernando_Botero

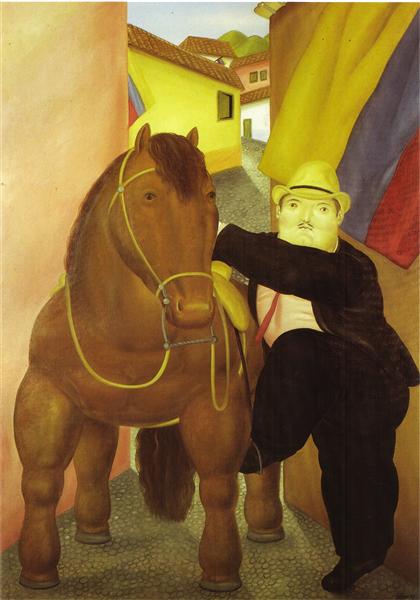

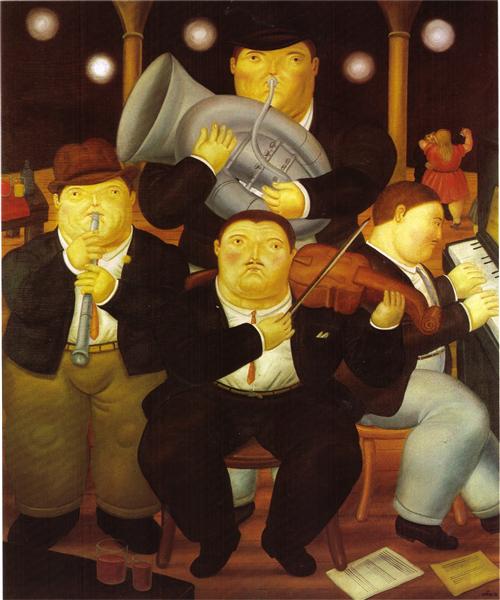

Fernando Botero Angulo (born 19 April 1932) is a figurative artist and sculptor from Medellín, Colombia. His signature style, also known as "Boterismo", depicts people and figures in large, exaggerated volume, which can represent political criticism or humor, depending on the piece. He is considered the most recognized and quoted living artist from Latin America, and his art can be found in highly visible places around the world, such as Park Avenue in New York City and the Champs-Élysées in Paris.

Self-titled "the most Colombian of Colombian artists" early on, he came to national prominence when he won the first prize at the Salón de Artistas Colombianos in 1958. Working most of the year in Paris, in the last three decades he has achieved international recognition for his paintings, drawings and sculpture, with exhibitions across the world. His art is collected by many major international museums, corporations, and private collectors. In 2012, he received the International Sculpture Center's Lifetime Achievement in Contemporary Sculpture Award.

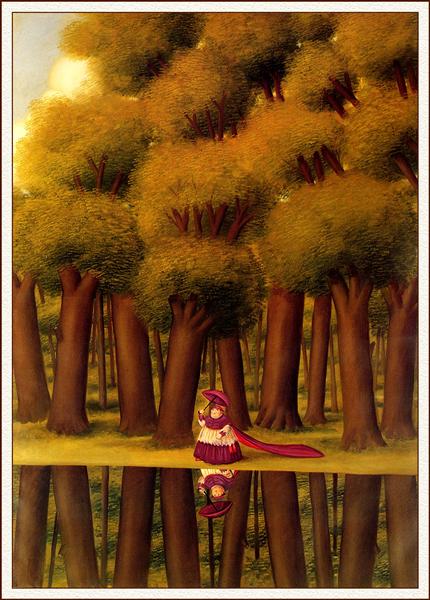

一直對於 Botero 的畫作很感興趣,較為大家所熟知的模仿名畫的一些作品,像是達文西的〈蒙娜麗莎〉、波納德的〈浴缸的女子〉或是凡‧艾克的〈阿諾菲尼的婚禮〉等,所謂的「圓滾」風格很容易讓人印象深刻;事實上,他的畫作不管是肖像畫、靜物畫,或是風景畫都能一以貫之。

從圖書館借到這本 1992 年 Prestel 出版的畫冊,其中收藏了 1986 年 Botero 在慕尼黑的一場訪談 (conducted by Peter Stepan),有些問題很直白,甚至尖銳,但從 Botero 的應答內容可以知道他絕非泛泛之輩。更重要的,關於 Botero 的創作理念及其作品欣賞之道,從這些問答之中,我們應該可以領略一二。

【Selected Paintings】

【Excerpt of the Interview】

Could you define the message behind your work?

Actually, there is no message. For me, painting means creating a poetic work from a particular stylistic standpoint. That’s the way it’s always been done. All the great artists of the past were able to create the illusion of something that exists, from a quite specific stylistic standpoint.

But the results are not purely aesthetic; they have resonances, they convey something.

Well, yes, but my chief concern is with the so-called decorative aspects of painting. Of course, expressive elements enter my work, but they result from the decision to do a good painting-and my main intention is to adopt a clear stylistic position and do just that. My work is not a commentary on reality

So you regard yourself purely as a painter; you’re not a philosopher making statements about the world. Does that mean you view painting exclusively as handicraft?

No, it’s more than that, because subconscious things enter one’s work in a completely natural way. When you start with the intention of painting an aesthetically, a stylistically clear work, everything follows naturally because it’s all there in yourself. But I am nor trying to comment on reality. Most people think my aims are satirical, but that’s not true.

Do you think your work could be described as a latter-day, South American development of the Baroque style?

No, not really. “Baroque” is not the right word to describe my paintings. I think the Baroque is centrifugal-look at the forces at play in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century sculpture. My work is the opposite. It is centripetal: its forces are quiet, looking for the centers of things in order to stay close to them. It’s not baroque, it’s abundant. Many things go into my paintings, but their relationship to one another is quiet-not baroque.

You have been one of the most consistent exponents of figurative painting, and were so at a time when it was the last thing in demand. Do you have a sense of continuity with the past, a sense of developing, perhaps perfecting, the centuries-old tradition of figurative art? Or is your work governed by a conscious return to figuration after the periods of abstraction in our century?

The kind of figurative work I do derives in a way from the experience of abstraction: it’s not the same kind of figurative art as that practiced before abstraction. My compositions are based on the requirements of color and form, so I often have to turn a painting upside down in order to view it as an abstract work. Abstraction has taught us to arrange colors and forms in a self-sufficient manner, so I need complete freedom in matters of proportion and, up to a point, in color as well. For example, if I need a small form somewhere in a painting, I can reduce the size of a figure. In doing so, I’m proceeding rather like an abstract painter. If I had to respect proportion and color I’d be robbed of this freedom, which is the most important thing for a figurative painter today.

Do you think the experience of abstraction gives you an advantage over earlier artists? Have you progressed beyond the stage represented by, say, Mantegna or Velázquez?

An artist is always a critic of earlier artists. It is a very strange mixture of admiration and criticism. You think you must, and can, improve on earlier ages. Of course, you don’t but the belief that you can is what keeps you working-it’s the curiosity to see if your idea works. And you naturally fail all the time-that’s what makes it so exciting. So you start all over again. Each day you think you’re got it right-and you continue to fail. You just keep on trying. Sometimes you’re better, sometimes worse-but you’re never actually right. You must have this critical attitude to art of the past, because you’re not here just to do nice paintings, but to attempt to arrive at absolute painting, using every means at your disposal to find optimum solutions to, say, the problem of plasticity.

Then there’s the matter of sensibility. Our sensibility is different from that of earlier times. Most people are more susceptible to the art of today than to that of the past because it belongs to the present-day world. An artist is able to let people experience the past with the feeling of the present. In a way, you’re saying: “I’ll do it better; I’ll do the art of today.” Of course, it’s not the art of the past. You can’t escape from your own time, so you’re creating something that belongs to the present moment-because once art has gone through an experience it never returns to its previous position. That’s why it impossible to fake Quattrocento or nineteenth-century paintings-they’ll always be twentieth-century paintings.

When it’s said that you turn to the past for inspiration, then in a sense that’s not true, for, to you, the past vas for a long time the present. Having grown up in the Baroque, as it were, your position is not really that of a twentieth-century painter referring back to seventeenth-century motifs and techniques because, for a Colombian artist, the two are much closer than that.

In a way, yes. We were very backward. Our mentality was completely different. We lived in isolation. Of course, I’m not saying that we didn’t have any books-we did! But geographical factors are immensely important. The Andes are one long chain of mountains, running from Patagonia to Colombia. Between the Andes and the sea lie the valleys of Chile and Peru. These countries are open to the world; they’re not separated from it by mountains. When the Andes reach Colombia they divide into three, creating valleys and plateaus. And that’s where the towns are-isolated. For instance, going from Bogotá to Medellin takes twenty minutes by plane, but if you go by car it takes twelve hours because you have to cross the Andes. They make communications very difficult. And roads were expensive to build. When I was a child, the roads went about twenty miles out of town and then you had to get on a horse. I’ll always remember seeing the horses at these points. How can you paint abstract pictures if you have to ride a horse all the time?

You’ve given many interviews, and in all of them have been asked about the voluminosity of the figures in your pictures. Does this corpulence express the mental or spiritual state of the people depicted? I’m convinced you’ll tell me that it’s a formal problem!

Every interviewer has to ask that question. It can’t be avoided because it touches on something absolutely central. An artist is attracted to certain kinds of form without knowing why. You adopt a position intuitively; only later do you attempt to rationalize, or even justify, it. I’m attracted to painters of the Trecento and Quattrocento-Giotto, Masaccio, Uccello, Piero della Francesca-and to such later artists as Rubens and Ingres. They all depict figures of a certain fullness; they paint what is referred to as “fat people.” You’re attracted instinctively to a certain kind of art and your work takes a similar direction. Then you start reading books. Bernard Berenson’s Italian Painters of the Renaissance, for instance, helped me a lot, because he proposes a scale of values in art based on the capacity to produce what he calls “tactile values.” He’s right when he says, for example, that composition and color had existed for centuries, but that it was Giotto who lent them three-dimensionality.

Giotto gave the viewer the feeling that he or she could touch the things in his paintings. He created a genuine sense of space in his images and thus, in a way, initiated what we now call the Italian Renaissance. If you look at the mosaics in the Baptistery in Florence you see that Berenson was right: the compositions are those used by Giotto, but he imbued them with tactile values.

Berenson attached great importance to the ability to create volume and space. Reading his book confirmed in rational terms the things I’d felt instinctively. I realized the importance of plastic values. The book came as a revelation to me, but it described in words something that had already existed inside me.

Does it ever happen that a painting turns out so completely differently from your initial concept that you’re forced to relinquish that concept?

No, never. When you start, you’re clear in your mind about perhaps twenty percent of the painting. In a way you know everything about it without knowing anything, because you know what you’re going to paint but not where it’s going to lead you. You just get on the train and let it take you. The rules, or logic, of painting oblige you to do certain things. You have to follow without preconceived ideas.

Let mc give you an example of what I mean. A few years ago I went to a Picasso exhibition and saw this wonderful blue-deep ultramarine blue with just a touch of white. Now, I’d banished ultramarine from my palette twenty-five years before. I’d always used cobalt blue because it’s cooler. By mixing it with a little red you can arrive at a color similar to ultramarine. From red you can’t go to green, but you can go from green to red: if you add red to green it becomes red. But you cannot take the red out of ultramarine. That’s why I like cobalt blue. Anyway, I was so in love with Picasso’s blue that I wanted to use ultramarine again; I couldn’t wait to put it in my pictures. I did so, and the results were catastrophic. I had to remove all the blue. Everything became so complicated; I had to change this, I had to change that, and so on.

And all because I didn’t follow my natural path, but had this preconceived idea of using ultramarine. It’s far better not to know anything about the colors you’re going to use.

Your pictures show an intact world: families, children, toys-snakes!-all coexist in the kind of perfect harmony that one associates with naive art.

There’s a difference between naive painting and mine. The naive painter works in the way he does because his knowledge is limited. His world of images consists exclusively of what he sees, and his technique is so elementary that the results are genuinely naive. In other kinds of painting the artist knows exactly what he’s doing. The fact that he or she happens to do figurative pictures doesn’t mean that these are naive. My subject matter is naive-that kind of paradisiac reality is naive-but my approach to it is governed by a high degree of consciousness.

字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大