字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2009/06/04 05:00:27瀏覽1083|回應2|推薦5 | |

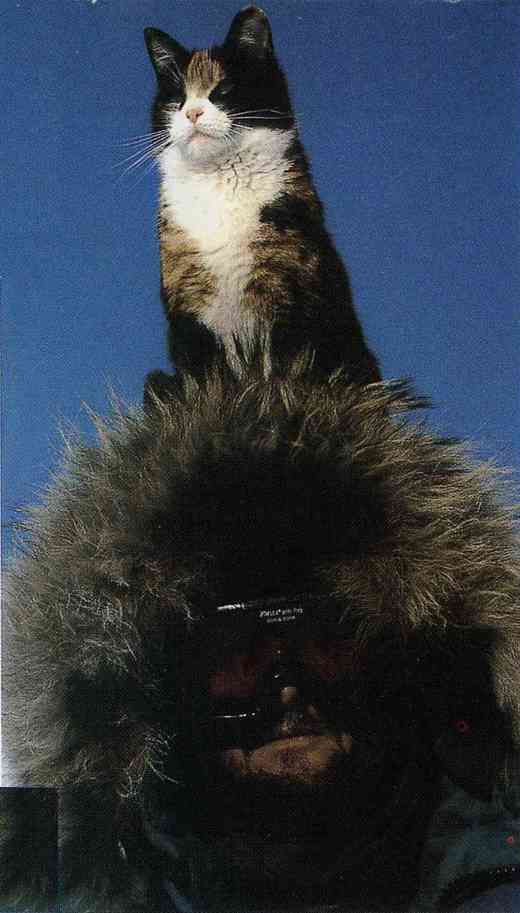

幾年前, 讀了一本書 “北航向永夜”(North to the Night); 書裡的情節人物如今一片模糊, 只有這張相片裡的小野貓永遠也不會忘。 一隻隨主人到北極一年的小花貓, 依天生有的野性加上點小頑皮, 竟磨練出探險家的氣質 - 好奇, 冷靜, 機智, 勇敢, 堅毅。 It's SO impressive。 動物世界比人想像的要複雜太多。 Halifax, 是個人物。 在 Alvah 的筆下, 活靈活現的。 Halifax 跳上跳下, 輕功了得, 像一片柔軟輕盈的羽毛(Alvah 語)。 能跳竄於兇猛的北極雪橇犬之間, 游刃有餘, 還興奮刺激地吱吱發噱, 洋洋得意。 能與北極狐, 雙目對峙, 嘶嘶作響; 勇於向前, 主控場面, 大聲警告, 直到北極狐夾著尾巴回頭, 還窮追不捨。之後, 愈玩愈大, 玩到北極熊的頭上。 不時地捉弄 Alvah, 玩 hide and seek。 一付“你過來啊, 你敢就給我追過來啊。” 撒尿在 Alvah 的枕頭上, 是她給的見面禮。 當然, 也有玩過頭的時候。 左耳凍掉了一半, 應聲而斷, 另一半可憐巴巴地 掛在眼前。 哈哈。 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Couple years ago, checked out an book about expedition, named "North to the Night", from the local public library. The story line and main characters in the book, now, turn into a blurry image, but this several month old calico kitten. The author Alvah and his wife Diana purchase the calico kitten in the market of Halifax port, Canada, before departing to North Pole, for the purpose of the bed warmer and polar bear detector, then name her Halifax. After a year stay with Alvah in the North Pole, the wild mischievous cat Halifax grows and becomes an expeditioner herself with the disposition of curiosity, coolness, wits, courage, endurance. It's SO impressive. In this expedition with Alvah, Halifax is really something. "Heavy Winds Howl off the Inussuakuk Glacier, whipping Tay Bay into a winter tantrum, trying to huff and puff andblow my house down. How long has this blizzard blown—two, three days now? What does it matter? The sun vanished months ago, leaving this wasteland cloaked in blackness and lifesucking cold. An hour, a day, a week, they all feel the same to me, huddled in this sleeping bag, sealed in my solo tomb.When the sound becomes muffled, I know our ice-trapped yacht, the Roger Henry, has disappeared completely beneath the drifting snows. If I can, I'll dig my way out when the winds abate. If I cannot ... well, that takes care of itself. The nerve-shattering shriek of those winds is now only a dull groan. If I could vocalize my aching loneliness, it would sound exactly like that. I have tried so hard to adjust to the darkness and solitude. I even triumphed momentarily, but in the end it was futile. Light and laughter are the core fuels of the human spirit. Halifax, my calico kitten and only companion, is buried deep beneath my feet. I listen to her breathing, grateful for her company but concerned for her survival...." page. 3 "We'd stopped in Halifax to relax and relish our final days of hot water, films, and fine meals. We would be forgoing these luxuries for a year at least, and if severely trapped in the ice . . . well, we weren't talking about that. Never give your worst fears the breath of life. We went to a flea market early on Sunday morning in search of the odd bits of this and that. I saw Diana looking into a cardboard box, and her serene smile left no doubt as to the contents. I looked in the box; one kitten was beautiful, mewing contentedly, a precious little peach. The other, a little female, was motley and mean. She spat, hissed, and tried to tear great hunks out of any hand offered. Diana could not decide, so I told the woman to give us the wild one. On the long walk back to the boat, with scratched and bleeding hands, we settled on the name Halifax. Due to limited space on a yacht, every piece of equipment must serve at least two functions: she would be our bed warmer and polar bear detector. Months later, when I needed one like at no other time in my life, she was also my friend. Having said that, we got off to a rocky start. Halifax took to shred-ding my charts, scrambling across my computer keyboard precisely when critical weather facsimiles were being received, and most infuriating, peeing on my pillow. She took an obvious delight in tormenting me, waiting until I was watching and then letting fly. She might have walked the plank had she not quickly learned that only she could slip under the inverted dinghy on the foredeck. " Page. 46 "Here is a relationship best understood when compared to others. The horse extended the range, speed, and cargo capacity at which Europeans, Asians, and much later the Native Americans traveled. But horses require much water. Thus, in the deserts of Africa and the Middle East, the camel was indispensable. At the high altitudes of the Andes, llamas and alpacas shouldered the loads. Each environment demanded that its people tame a beast before taming their surroundings. In the case of the sled dog, the word tame is only marginally useful, for they are fierce, and their wildness cannot be beaten out of them. They often fight to the death in establishing their working order. The Inuit stand back, having always understood the process of natural selection. They admire and encourage this ningaq (fighting spirit), knowing that this spirit, once harnessed, finds outlet in the dog's will to pull beyond natural limits. Ningaq has its risks, too. Every so often an infant wanders within the range of a chained dog pack and is torn to pieces. A man is judged by the dogs he drives. The processes of breeding and training have become cultural rites of passage into manhood. I watched a woman pulling a miniature sled. A boy, no more than three years old, slid behind, cracking his whip on the ground, authoritatively shouting "Ili, ili, [right], iu, iu, [left]." When she stopped acting the dog and tried to act the mother by wiping his nose, he gave her a stern tongue lashing. She smiled, satisfied that neither dog nor woman would ever dominate her son. Cats are a rarity, for they would be torn into tufts before you could say Halifax of the North. As we pushed quickly up the coast, in spite of our best efforts, at each port Halifax made her escape onto the town dock where dog packs roamed freely. I was a nervous wreck, having grown inordinately fond of the little beast, but she seemed to enjoy the titillation of narrow escape. That training was to come in handy later. In one port, we invited a man and his daughter on board. The little girl was fascinated, and even after holding and petting Halifax for some time, she had to ask, "Papa, is it real?" Page. 62 "As we passed the mouth of Melville Bay, we tucked in behind a small island and anchored for some much needed sleep. I tossed and turned in my berth, knowing there would be no real rest until we made the big decision: go or no go. At low tide the icebergs in the bay grounded, so they posed no immediate threat to the boat and wouldn't pin down the anchor. I asked Diana to go ashore with me for a climb up a high hill where we could assess the ice conditions in the bay. We rowed toward a black stone beach with Halifax sitting in the bow, quivering in anticipation. In an impressive but ill-timed leap, she fell just short of land. Very hot and very cold feel much the same; she shot out of the sea as if scalded. We dried her off with clothes from the emergency shore box, and then the three of us bounded uphill over the rocky tundra. .......................................................................................... Diana withdrew into herself, wrestling with her fears. When the chilly late-August winds pierced our clothing, we hiked back down the hill. Halifax understood perfectly that to get in the dinghy meant going back to a boat void of nice stinky scat and carcasses. She backed into a small cave created by two lichen-stained boulders. " Page. 70-71 "After three days the storm vented its rage, and conditions abated a little. Relieved, I thought our ordeal would soon be over. By chance I looked back and, heading out over the last ice pan, skipped a happy Halifax. Our thoughts were of survival, hers of freedom. Philosophically, she outranked us, but I was plenty mad just the same. We raced back. I scrambled over the treacherous ice while Diana fought to control the vessel. The more frantic I became, the louder I shouted, the farther Halifax fled. Finally, I sat on the ice as if it was a quiet day in the park. Halifax ran back to me, enticing me back into the chase. I pounced on her and pressed her back into onboard service." Page. 81-82 "I was alone again, and given their news about the stir in Pond Inlet, I dearly wished I would stay that way. For three days worry churned my stomach. I monitored the southern skies for invaders and practiced my speech, designed to shame a low-level functionary into inaction. Days passed, and when a real ripsnorter blizzard began to blow, I knew I was out of the woods. I had kept a strong and confident face for them. "Look me right in the eye." Did I really say that? What could I do, tell them the truth? "I agree, gentlemen. This is just not safe. You should see what's already happening in my head." The nightmares began almost from the outset. Denied emotional outlet through the solitude of the day, I found that every otherwise in-significant insecurity or conflict flared up into a full-scale, cross-border war between reality and my subconscious. I kick down the door and throw my hands around the throat of the bastard in bed with Diana. I squeeze past the pain of his punches, past his pitiful little thrashings, past his bug-eyed plea for mercy. I'm screaming, "You fuck with my life? Fight, you big son of a bitch. Don't just die! Fight me!" Diana is pummeling my back with her fists, screaming, "Stop! Stop! That's why I hate you. You're an animal!" She is scratching me, she is Halifax, Halifax is scratching me. That's pain. Am I awake? Oh God, God, it's only Halifax. I'm thrashing, and she's just trying to get out of the sleeping bag. I'm sorry, Halifax; I'm sorry, Di; I just lost my temper. I'm not an animal. Forgive me. I reach up to open the ice-encrusted porthole on the wall of my aft cabin cave. I punch a tunnel through the snow, and Halifax springs up and out into the cockpit. The boat acts as a guitar, and her footsteps in the dry snow reverberate through the cabin, sounding like a bear's. Thick air flows over my face like the River Styx. It freezes my sweat and shocks my lungs with my panicky panting. I remember other dreams: The boat was crushed; a bear was pulling out my intestines and I had to grab the slippery tube like a rope in a deadly tug of war. But I never once dreamt that I was cold." Page. 129 "Feeling cold meant I was awake. The heater was out again. Snow must have drifted over the flue pipe. Even though the end of my nose felt wooden with frostbite, I couldn't bear to pull my head back into the sleeping bag just yet. It was no darker inside than out, but the bag was shaped like a coffin. I pulled on my Darth Vader facemask and wondered if my eyes were open. My ears sucked in signals—Halifax was back. I let the shivering cat into the sleeping bag and lay awake until the rose-petal light of late dawn seeped into the boat. " Page. 130 "standing on the ice is a danger, but one lying on the ice is dinner. Halifax crawled into my parka hood, clearly respecting the danger the large carnivorous bird posed. We remained still as the bird lit on an iceberg just above us. I recalled Steven Young's To the Arctic: "Omnipresent scavengers, predators, and observers of the Arctic environment, the raven is considered the most intelligent of all birds. It figures prominently in the mythology of northern peoples." .............................................. The raven is perhaps the Arctic's keenest judge of probable outcome. This lone bird had chosen not to fly south for the winter, and I thought I understood what that meant. I said out loud, "Listen to me, Raven, I'm going to live through this. If it's food you're after, then you better follow that sun south now, because there's no hope for you here. Halifax is smart, and I'm stubborn." ................................................ Still lying on the ice, I said out loud, "Halifax, I've been thinking. I'm already screwing up big time." To the Inuit, to lose your temper is to lose your dignity, and they have little else. They contain and control anger, as if letting the heat out allows the cold to creep in. The Bush-men of the Kalahari call whites "The Angry People." I wondered, What is all this anger in me, all this emotion? The Arctic won't kill us—I will, with these impulsive outbursts, tantrums, and careless behavior. This will not be forgiven up here, not up here. In perfect control, I might just make it. Out of control, I'm as good as dead. .................................................... I picked myself up off the ice and trundled back toward the boat. Halifax followed like a dog. At regular intervals she clawed her way up my back to thaw her paws. She leapt down to entice me to chase her around a small berg, then ran ahead to hide in the snow, and pounced on me as I passed. She was having fun, and that was no small thing. I might learn from her animal version of The Unbearable Lightness of Being. She stopped with her lips curled back, sucking up a cornucopia of odors from a big piece of frozen scat and yellow block of urine. She looked at the maze of tracks around us and then at me as if to say, "We're surrounded!" She loved those hikes. She lived for them. And soon, so did I. " Page. 132-133 "I went below and pulled up a floorboard, exposing the ice-choked bilges. I chipped free a plastic bag of old rigging wire. Unwinding the fine wire's kinky plaits, I planned to splice them into a hundred-foot length. To keep my fingers warm and functioning, I had to do the splicing below, in spite of the limited space. The spiraling wire spread about the cabin in tumbleweeds, the loops and whorls just far enough apart to prevent them from contacting one another—that is, until Halifax waded in. With two or three quick sorties, she tangled the wire into a rat's nest that overwhelmed the cabin. The more I tried to untangle it, the more entangled I became, like a cheap science-fiction plot. I spent the better part of the day taming the wire. (I was less successful taming the cat.) After many long splices, the wire was finally at one with itself. " Page. 137 "I often sat in the dark for a couple days to save up energy and then really splurged by lighting two lanterns, perhaps even a candle. The light was glorious. It cheered the atmosphere and warmed my soul. But most importantly, I could read, exercising my eyes and mind. Compared to the continuous blizzards and average outside temperature of minus thirty-five degrees, I found my refuge acceptable. Halifax disagreed. Mostly, she huddled deep in the sleeping bag, emerging only if her keen ears detected the sounds specific to me thawing out her block of milk. When one sleeps in a heavy hat, gloves, and thick clothing inside a tightly tapered sleeping bag, space is at a premium. We often had territorial disputes. She usually won, for she was better equipped to dig in when push came to shove. If I tried to force her out of the way, she would curl her lip, flex her claws, and give me a "go ahead, make my day" stare. One day, as she walked from the bag bottom over the length of my body to get out for some fresh air, I noticed that she felt surprisingly light. I had not stocked much cat food, thinking that she could eat what we ate, but no matter her hunger, she would not touch the smoked meats. I turned on an electric light and saw that she was alarmingly thin. In the energy-demanding Arctic, one can starve to death almost as quickly as one can die of thirst. I searched for the best medium with which to convey fat into her little stomach. For the baking of bread, the Joy of Cooking told me to "let dough rise at room temperature for two hours." I took one look at the thermometer and devised Plan B. I took the full mixing bowl into the sleeping bag, hoping to use my cocoon and body heat as a proofing oven. It was a slow process. I fell asleep, rolled over, and spread the gooey mess everywhere. I woke to Halifax licking the slop off my face. For my next attempt, I wrapped the dough bowl and a hot-water bottle in a woolen blanket. Maybe I checked its progress too often, because the result was a loaf with the texture of oak through which even feline fangs could not cut. The effect of the gas blowtorch on the next globule was equally discouraging. ...................................................... I economically produced some handsome loaves of white, wheat, oat, cornmeal, onion flake, and combinations thereof. Halifax did not offer up a purr easily through those dark days, but a bowl of warm diced bread saturated with butter and oily tuna evoked at least a hint of grateful rumble." Page. 158-160 "The days flowed by seamlessly, emotionally some good, some bad, physically all dark and difficult. Normally only two national holidays hold any meaning for me—Thanksgiving and Martin Luther King's birthday—but I was looking for excuses. I would have celebrated National Hemorrhoid Awareness Day. On Thanksgiving Day, I cooked up a sumptuous feast. Halifax knew something was up, so she hung on my shoulder like a fur collar to watch my every move. I mashed canned turkey with dried vegetables and made a meatloaf shaped like a bird, surrounding it with mashed potatoes with gravy and soaked, dried cranberries. I baked pumpkin tarts and poured my last can of cream over them. Halifax ate two, then curled up contentedly on my chest. " Page. 163 "I got up and went through the cumbersome exercise of dressing for the minus-forty-degree cold outside. With a kerosene lantern in hand, I crawled out onto the buried deck. Fox prints covered the snow. Halifax followed me, her tail puffed up like a raccoon's. She was mad at me; after all, a deal is a deal. It was my job to fend off the foxes and bears so she could take her daily constitution. She dug a hole in the cockpit snow, squatted over it, very smartly did her thing, and dove below. ............................................................................ In my dreams, I find Jon alive. A tall, athletic man catches a Frisbee in a park, and I know it is him because I know how he moves and I recognize his unique handsomeness. I dreamed he faked his death to avoid the draft or be-cause he was gay or HIV-positive and could not tell his wife and family. In each dream I create another reason. In each, when I call to him, he tries to run. I catch him and we wrestle. Jon was always bigger, stronger, and faster than me, but he could never beat me in a fight because he was the nicer man. In the dream, I always punch him hard, just once, for the pain he caused me, then I hug him with all my soul. Then I wake up and can't tell where I am or if the dream is true or not. Then I feel the cold, and I know, and I cry. It is not just me going crazy; Halifax's behavior is altering noticeably. The snow leopard is well suited to the cold but lives near the equator, so it never has to face extended darkness. Felines are not natural Arctic dwellers. Why wouldn't Halifax go as crazy as me? She has the classic symptoms of cabin fever. She whines and wails all the time. She is broody and petulant. How can you quarrel with a cat? But I do. She waits for me to watch, then she destroys things with obvious rage. She'd rather risk my wrath than be ignored. It is a dangerous game she is playing, because my temper is terrible, uncontrollable, and I don't know why. She was determined to lure me out of my bag by tearing up the foil on the backside of the forepeak door. I was determined this would be the last time. I had to teach her once and for all. I lit into her with the blind fury of a baby shaker. I could not believe that it was I doing this. I love animals. I have never been a cruel man. For the next two days, every time I tried to pet her, she bit me. " Page. 178-179 “Halifax charged straight for the fox. I was too slow and would play no part in the outcome. The fox sat still until Halifax was upon it, then it whirled around and ran for its life with Halifax hot on its tail. They disappeared over the snow dunes. After an agonizing hour's wait, Halifax reappeared in camp, clearly pleased with her performance. Diana and I were below when Halifax came streaking down the steep stairs and dove into the forepeak. I jokingly asked her if she was being chased by a bear. The next morning I did my round of the boat and was shocked to see her little adventure written in the snow—Halifax's footprints moving ahead of a bear's, at first close together at a walk, then spaced widely on a run, then the last of her prints leaving the snow in a great arcing leap for the boat, and the bear sitting down a full three strides away, no doubt pondering the strategic sight.” Page.182-183 "IT WAS CHRISTMAS DAY, but a blizzard howled outside, leaving little peace on this piece of earth. ...... I gave Halifax a whole can of tuna, unadulterated. I let her eat it up on the normally verboten galley counter as a treat. She slurped up the oil until the can shone in the candlelight. A month earlier I had found a gift from Diana marked, "Do not open till Christmas." I opened it now to find a small box of Fig Newtons, a special treat for me. I taped her card next to the radio and read it a hundred times. It said, "I love you. Diana." ................................................................ The wind howled outside, the boat shuddered, Halifax purred. I thought about my family at home, together, perhaps sitting down right then to a home-cooked meal, and my mind created before me the feast. My mother's honey-clove ham steamed at the head of the table, my sister's garlic-herb mashed potatoes were piled high on the heavy china plate being passed. The aroma of hot pecan pie wafted in from the kitchen. Everyone was laughing, even though it was the exact same story being told as was told last year and the year before. ...................................................................... I had a good Christmas, sober and reflective—perhaps a Christmas as they used to be, before we counted the shopping days leading to the blessed event. As I scratched all this into my diary, Halifax, who had escaped the sleeping bag, had scratched her thoughts into the soft spruce wood-work and waited in mischievous anticipation of my charge. In the holiday spirit of goodwill, I switched tactics. She is an intelligent animal. When she wanted a drink and could not lure me from my bag to thaw her dish, she unscrewed the large lid on the water barrel. Her little paws pushed the cap counterclockwise until it was loose. Then she shoved the lid to the floor. She stuck her head down in the barrel for a chilly slurp. This became habit, and I have collaborating eyewitnesses to prove it true, although when I told Peter Semotiuk, who knows cats well, he demanded photographic proof. If she is this damn smart, I reasoned, she should understand at least the intonations of this little poem I have just written in her honor. She stared at me as I read it aloud to her with dramatic flair: "Halifax, my cat, was furry and fat. Oh, a finer companion could not be. I was trapped in the Arctic, My life was so stark it Had no other warm company. And so side by side,the dark months we did bide, Huddled as bleak blizzards blew. And when the food ran out, At eight pounds thereabout,she made a fine and filling meat stew." The day after the Christmas blizzard, Halifax and I were huddled below when we heard the sound of footfalls approaching the boat. From their volume, I assumed they belonged to something very big—a thousand-pound bear, at least. Halifax puffed up like a porcupine. Right over our heads paced a tremendous crunching, as both our heads swept back and forth like radar tracking enemy sounds above. What-ever was up there had our undivided attention. I waited for the beast to rip the hatch away. Then I noticed that the footsteps were rapid, unlike those of a lumbering bear. I swore, realizing we were the victims of an Arctic audio illusion. I crawled out of the bag, got dressed, and poked my head out the companionway. Standing perfectly still in the cockpit, two feet from my face, was my belated Christmas present—a personal visit from an arctic fox. He did not run, but stared directly into my eyes with an intense inquisitiveness. His eyes reflected emerald green in the light of my head-lamp. He looked like the fox from my dreams—pure white, fluffy, keenly intelligent. ...................... For the next two days he visited the boat often. Halifax began wailing; she had to get out to do her business but dare not as long as I let this intruder hang about. When Halifax hissed, I knew the fox was visiting. It was a beautiful animal, but full of fast fangs and driven by extreme hunger. I had also been warned about a high incidence of rabies in the arctic fox population. I imagined the progression: He gives it to Halifax, she gives it to me, I foam about the mouth more than usual and die in agony. I knew what I had to do............................................... ON NEW YEAR'S EVE I threw a party, and everybody came. I baked a pizza, turned on the lights, cranked up the stereo, and cracked the bottle of brandy. I chased Halifax around the cabin, teased her with a raven feather, and let her tear up one of my charts. She careened off the walls and whirled in mock battle, clearly having a wonderful time. She passed out under my knees and purred so loudly it woke me. For a terrible moment I thought a helicopter was coming. Why can't they leave us alone? Then I knew it couldn't be—they do not dare fly in the inky, Arctic night—and I felt happy. " Page. 187-192 "Halifax woke me two days later, persistently pushing her paws into my face. I was so used to waking to total darkness that, for a moment, I forgot about my problem. Then I bolted upright and grabbed for a flashlight. I passed the beam over my eyes. It hurt like hell, but I could see! I had to ease my way back to the sighted world; every time I tried to read for even a minute, that terrible wave of nausea washed over me. Fear persisted in spite of my relief. Reading and writing had become my only anchors in the turbulent ocean of time. To cast those away would set me dangerously adrift. " Page. 199 "Once more I sank into a black funk and could not shake the negative thoughts chasing each other around my brain. The chatter was driving me mad and I had to hike it off, no matter the forty-five-below cold. I kitted up and set out through the moonlight with Halifax on my heels. We had hiked before at these temperatures, and she loved it. I couldn't understand why this time she lagged behind, whining. "Come on, Puss. Come on!" I urged as I hiked toward the shoreline. I looked back, and she remained far behind. When I called, she came halfway and then sat down in my tracks. Angry, I shouted, "You wimp!" and stomped off up the hill to Thinking Rock. She hated to be caught out too far from me, so normally if I outpaced her early she turned back to the boat. But we were past her point of no return, and I was sure she would follow. Halfway up the long hill I looked back through the dim lunar light. She was a little black speck in the snow, immobile. I knew something was terribly wrong. I ran down the hill to her. She sat stiffly, staring at me, seemingly half-frozen to death. I picked her up and tried to push her into my coat. Her right ear cracked in half and hung down on her cheek. My God! What have I done? I ran all the way back to the boat. I took her below, put her in the sleeping bag, and lit the heater. I tried to get her to drink some warmed milk. She lay stupidly still. I pulled her ear back together while she still had no feeling in it. As she warmed, the pain started; she howled in agony, and my heart broke with pain and guilt. Just when I think I am doing so well, I do something so stupid! What is wrong with me, shouting at a cat that she is a wimp? How can a cat be a wimp? The signs were there. The wind freeze-dried her ears, you fool. That's why there are only dogs up here—cats can't drop their ears. She tried to tell me, but I wouldn't listen. I hugged her in the bag. Please, Halifax just heal, and I will take care of you for the rest of your natural life. I'm not like this normally. It's being out here. You get scrambled, you make mistakes. Forgive me. Her pain grew worse as the days passed. Her ears puffed up, wept, and finally scabbed over. The broken ear seemed to be growing back together, although with a permanent droop. She shook her head as if she was crazy and furiously tried to scratch off her ears. I had to hold her little paws while we slept. Those were long days for us both. When she fully healed, her jet black ear tips had turned a permanent, snowy white. To this day, they act as a reminder to me that, in nature, all I need to know is there if I simply look and listen. " Page. 200-201 "I closed the diary and turned my thoughts to Halifax. If I died, she would wither away or be forced out to forage and fall prey to foxes. It was an unbearable thought. Next to Diana, she was my best friend on this earth. We had come so far together. What could I do? I thought hard, then I smeared a dab of honey on my stomach, which she licked off. I smeared again; she licked again. If I could get her to associate my stomach with food, she had a chance. I would die in the bag with her curled up next to me. Her own heat would keep that part of my corpse thawed. She could then get at my soft underbelly for a lasting supply of food. Still, I knew her chances would be slim. Once my body was discovered and the truth of her survival obvious, she would be shot in disgust. How could they understand? They were not locked in our realities. Halifax, Raven, and me—we understood. " Page. 203 "In the dark, Halifax offered a little mew as if to say, "Pull yourself together, man!" That struck me as so funny that I laughed even harder. I howled, then sobbed, and finally quieted to pitiful whimpers. I lay on the floor, cold, exhausted, and as ashamed as if caught masturbating. I made my way to the bag and crawled inside. The episode was over but not forgotten, for I never fully regained my previous confidence. I was always on the alert for some snap in my behavior, always fearing a tail-spin into delirium. " Page. 206 "My heart pounded through the agonizingly long commercials. I grabbed the chart of Baffin Island and, with parallel rulers, marked off the miles separating us—a mere seven hundred as the Raven flies. Winston welcomed Diana to the studio, explaining to the audience that he had heard of her return and met her at the airport in the hopes of a live interview. She had some layover time and agreed, provided he wouldn't mind first swinging past a grocery store for thirty-five pounds of cat food, the last item on her shopping list. Halifax of the North was a big hit, and Winston made good humor about her being the Canadian representative in the expedition. He asked Diana to describe our purpose, journey, and the events that had separated us. She did so with no embellishment or hype. Her beautiful voice brightened the cabin like a light. Halifax sat on my shoulder, staring at the radio, her little head cocked in question. First commenting on how fast news travels in the North, Winston said that everyone who had heard about our situation had expressed grave concerns. He asked if Diana thought our adventure was too risky, perhaps even reckless. She said that, in fact, she was proud of ....." Page. 223 "Halifax hiked beside me, mile after mile. We wondered over a rotten seal flipper two miles inland, and we squatted over a bear track two hand-spreads long. We sniffed the air and looked around carefully, then back at each other. I wondered what this experience had meant to her. Why had I even once thought of myself as being alone? Every five minutes Halifax leapt on my shoulder to warm her paws and hitch a short ride, then something spectacular like a feather or fox track would lure her down." Page. 226 "on the southern slope. I heard nothing, but I had faith enough in her superior senses to ski across the sea-ice, through the broken ice boulders, past the sheets heaved upon the shore, and then strap climbing skins on the skis to trudge up the tundra to the cliffs above the inlet. I turned my hood south and sat silently. I hear Raven . . . a ptarmigan . the usual pings, pongs, and cracks of ice movement ... but nothing else ... Yes, there! A faint sound like an insect, but my eyes could not stretch as far as my ears. I could see nothing but ice and snow for miles. Halifax bounded up beside me. I followed her gaze to an ice-boulder field three miles down Navy Board Inlet and well across the other side. "No way, Halifax—why would they be way over there?" I trained the binoculars on that spot. Around a block of ice I saw a small speck creeping forward. It seemed too small to be a snowmobile and sled. But it was just that the ice block was so large. I paced the snow-covered tundra in excitement, watching them wind their way through this unfathomable scale and fantasizing our reunion a dozen ways until I settled on one I liked. Then I realized that if I did not head back to the boat quickly, they might beat me there to find an empty camp. I raced hard down the slope through the broken shore ice, tumbling head over heels. I sorted out the tangle and skied hard, but my skis felt glued to the ice. They were—I had forgotten to take off the climbing skins. I ripped them off and set out again, working up a real sweat, thinking, How very un-Inuit of me. Well, today is special. Halifax, lithe and light as a feather, passed me in a flash, streaked for the boat, and dove below.” Page. 232 “Sleep did not come as easily for me. I could hardly stand all the excitement, the people, and the talk. After that wore off, Halifax kept everybody awake by scratching the foil until I got up and let her out. Then I worried she would not understand the extreme danger those fifteen canine beasts posed. Should she wander near them, they would tear her to pieces. I felt nauseous at the thought, so I dressed and slipped out. Halifax stood just out of their range, engaged in a silent staring contest. When I picked her up, she purred with delight over her exciting game. “ Page. 251 “Hemmy cached two dead seals deep in the snow as a food supply for a dogsled team expected this way in the coming weeks. The Arctic was awakening, and the word was out: Our home was open to all. Inuit hunters felt free to drop in for a hot meal, a soft bed, and to see the now-famous Halifax, an animal strange and exotic to them. We would become a rendezvous point and forward base camp for the spring hunting season.” Page. 256 “As I SCRATCH THE LAST LINES of this long work, Halifax scratches at the front door of our rented home on the wooded shores of Penobscot Bay. She is full grown now—perhaps too full grown, for we cannot deny her a single treat after all we put her through.” Page. 323

|

|

| ( 在地生活|北美 ) |