Arendt’s Insights Echo Around a Troubled World

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/09/arts/09conn.html

By EDWARD ROTHSTEIN

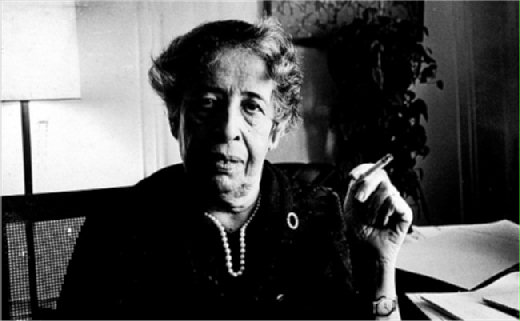

Hannah Arendt was a philosopher of the exceptional. But as the centennial of her birth approaches on Saturday, she can seem more like a philosopher of the typical.

After she saw her native Germany nightmarishly reconstitute itself into something monstrous, she tried to comprehend what had happened with the rise of Nazism and the parallel rise of Stalinism. These phenomena were, she said, unprecedented. In “The Origins of Totalitarianism” (1951) she cataloged their characteristics: sweeping ideologies, death and concentration camps, vengeance against imagined conspiracies, imperviousness to political challenge. Together, she wrote, these characteristics “exploded” the familiar concepts of politics and government: “the alternative between lawful and lawless government, between arbitrary and legitimate power.” The lawless was made lawful; the arbitrary became legitimate. All categories were broken down; new ones needed formation. In the future the exception would shape a new rule.

And, to a great extent, with varied and vexing consequences, it has. Whether the world itself has changed (as she proposed), or our interpretation of it has, or both, it is no longer possible to discuss political life without in some way invoking those phenomena that once seemed so exceptional, without forming analogies to them, and without considering Arendt’s concepts that developed around them.

The Arendt centennial is now being celebrated with conferences and lectures in locations ranging from Germany to South Korea, from Kosovo to Australia (information: hannaharendt.org/conferences/conferences.html), and one theme keeps recurring. When Arendt analyzed totalitarianism, introduced the idea of the “banality of evil,” emphasized distinctions between private and public life and tried to articulate a new philosophy that would reconsider the nature of thinking and judging after both had become scarce, she could just as well have been speaking to us of our time, addressing contemporary debates.

So it is no accident that in discussing Arendt’s importance more than 30 years after her death, Iraq and terrorism are often mentioned alongside her views of power and violence, statelessness and totalitarianism; her most solemn assessments of the traumatic past become warnings for the imminent future. That is part of the polemical point of a new book, “Why Arendt Matters” (Yale University Press), by Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, the author of an Arendt biography; she will lecture on the subject Thursday at the CUNY Graduate Center in Manhattan.

Beginning on Oct. 27 at Bard College (where both Arendt and her husband, Heinrich Blücher, are buried), a three-day conference, “Thinking in Dark Times: The Legacy of Hannah Arendt,” is to feature two keynote speakers about that legacy whose contemporary analogies may differ: the political journalists Christopher Hitchens and Mark Danner. (Information: www.bard.edu/arendt/overview.) And just over a week ago, at Yale University, a conference on Arendt alluded to current controversies in its title, “Crises of Our Republics,” with many speakers amplifying the allusion.

But something strange can happen in the midst of these comparisons. The exceptional provides the analogy for the present. The extreme becomes a model for understanding what is less extreme. The unprecedented remains ever-present, serving as a recurring admonition and an insistent demonstration, a guidepost for understanding politics itself. Even today when there is horror enough in the world, even when varieties of totalitarianism and genocide can be plainly found, the analogy insistently seeps into all cracks and distinctions dissolve. Societal flaws or flawed policies of democratic nations can start to seem as flagrant as the practices of totalitarian systems, because they provide glimpses of what might yet come to be.

This is a perspective Arendt occasionally fell prey to as well. She worried, for example, over incipient totalitarianism in the United States if Senator Joseph R. McCarthy became president in 1956, an unrealistic worry not unrelated to personal fears over her husband’s Communist past in Germany and her own experience of displacement and exile. Ultimately her sense of the democratic resilience of the United States was restored, but for Arendt, as for many of her readers on the political left, a crucial lesson of her anatomy of totalitarianism was that it could indeed happen here.

This may also have been one of the subterranean implications of Arendt’s most controversial book, “Eichmann in Jerusalem,” in which she introduced the idea of the “banality of evil,” giving a portrait of Adolf Eichmann as a Nazi bureaucrat without startling personal qualities, passions or hatreds, whose paper-pushing sent millions to their deaths. There were numerous problems with Arendt’s portrait (and with the concept as well) but it had the impact of a morality tale. Listen, she seemed to say, if radical evil is found in a banal bureaucrat, then why couldn’t it happen anywhere? Particularly if, as was the case in 1963 when Arendt was writing, even Western bureaucratic life had started to be seen by writers as intrinsically tainted?

That possibility was also a recurring motif for many speakers at the Yale conference. Of course there are serious questions to be asked about how Arendt’s categories can be applied to the contemporary scene, and as Samantha Power, who teaches at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, pointed out, the experience of statelessness and powerlessness is now part of the modern condition. It is no wonder Arendt’s ideas are widely cited. But how far should they be taken and where should they be applied? The political scientist Benjamin R. Barber, for example, dismissed the idea that Islamist fundamentalism was in any way totalitarian but suggested that given the current administration in the United States, an “American Eichmann is not altogether impossible.”

“I feel the American Republic is in the deepest crisis of my lifetime,” said the writer Jonathan Schell, fearing that though Arendt’s “checklist” for totalitarianism is only partly satisfied by current conditions in the United States, “we are on the edge of that abyss.” The philosopher Susan Neiman, the author of a subtle book, “Evil in Modern Thought,” interpolated her discussion of the crimes of Hitler and Stalin with wonder about whether more guilt should be ascribed to Dick Cheney or Paul Wolfowitz for the war in Iraq. The political scientist George Kateb, after giving a supple discussion of Arendt’s views of morality, turned angry when applying her ideas to the current scene, seeing “the rudiments of a police state” here, and finding evidence of the worst constitutional crisis since the Civil War.

But when the extreme becomes the frame of reference, as it often does in our post-Arendtian world, any resemblance to it — however intermittent and fragmentary — is seen in its harsh light. Democracy’s failings warn of totalitarianism. Why, though, even if the critics’ diagnoses are correct, do failings indicate an incipient apocalypse any more than virtues herald a utopian paradise? Such an approach turns the exceptional into the typical. Arendt sometimes did something similar yet was also wary of the consequences. But that is the temptation that haunts the many Arendt commemorations now taking place.

http://www.gmw.cn/01ds/2006-10/11/content_490897.htm

本報記者康慨報導 10月14日是已故著名德裔美國政治思想家漢娜·阿倫特(Hannah Arendt,1906-1975)誕辰100周年的紀念日,遍及世界各地的追思活動提醒人們,這位死去已有31年的女哲,在21世紀混亂的今天,仍然具有非同尋常的重大意義。

據總部設在紐約的非營利組織“漢娜·阿倫特協會”(Hannah Arendt Organization)統計,德國、法國、瑞士、瑞典、美國、澳大利亞,乃至秘魯、韓國和科索沃等地,都將舉辦相關的紀念活動。

所有這些活動都不脫一個共同的主題,即阿倫特對當下世界的意義。今年12月將在紐約舉辦的一次研討會的名稱,再恰當不過地說明了這一主題:“漢娜·阿倫特此時此刻”(Hannah Arendt Right Now)。剛剛在耶魯大學結束的一次學術座談,也以“我們共和政體的呼號”(Crises of Our Republics)為題。阿倫特生前的女弟子和其傳記作者伊莉莎白·揚-布魯艾爾(Elisabeth Young-Bruehl)的新著《為何阿倫特至關重要》(Why Arendt Matters),也於本月由耶魯大學出版社出版。

這一切都在告訴我們,阿倫特仍然是解讀當代世界的重要思想工具。

她飄蕩在別處

漢娜·阿倫特1905年10月14日生於德國漢諾威一個俄國猶太移民家庭,在柯尼斯堡長大,此地乃康德故鄉。她後來師從海德格爾和雅斯貝爾斯,1928年獲頒海德堡大學哲學博士,納粹上臺後流亡巴黎,二戰期間移民美國,長期任教於紐約社會研究學院。

阿倫特的主要著作有《極權主義的起源》、《艾希曼在耶路撒冷》、《人類的狀況》(一譯《人的條件》)和《論暴力》等。

今年,阿倫特的兩本著作——《精神生活》和《黑暗時代的人們》在中國內地出版。此二書雖非她最廣為人知的代表作,卻有助於我們拋棄過去不見原著,只談她與海德格爾不倫私情的大量庸俗文章,並有機會深入其思想深處。已經開始的系統譯介,也算對她百年誕辰的一份好的紀念。

阿倫特具有一種“讓哲學充滿生機並使它完成預定目標的能力,”耶魯大學教授塞拉·本哈比(Seyla Benhabib)10月4日對《紐約太陽報》說。她作為召集人,主持了前述“我們共和政體的呼號”研討會。

不過,即便在西方,對阿倫特的誤解也是長期存在的。正如前文所說,阿倫特難以為主流接納,且多爭議。

“你不能用左派或右派來給她歸類,”多倫多大學教授貝納爾(Ronald Beiner)說,阿倫特既非左,亦非右,“她飄蕩在別處。”

美國將成為警察國家嗎?

《紐約時報》10月9日的報導說,阿倫特生前是非主流的哲學家,如今卻更像我們時代的典型哲人。在她死後30餘年,人們之所以還在如此談論其重要性,是因為伊拉克和恐怖主義總是能與她筆下的主題——權力和暴力,以及無國家狀態(statelessness)和極權主義聯繫在一起。

美國會變成極權國家嗎?在很多人看來,這是個荒誕的問題,但阿倫特的確有過這種擔憂——她一度為麥卡錫會在1956年當選美國總統的前景而焦慮。現在,左派知識份子舊事重提,以此警告人們當心布希的濫權。

更應警惕的是阿倫特在《艾希曼在耶路撒冷》一書中所提出的“惡之平庸”(banality of evil)的概念:一個納粹體制內平平常常的小小官僚,沒有理論熱情,亦無明顯的愛憎,這樣的公文機器,卻將數百萬猶太人送入死亡的絕地。她的言下之意是,這平庸的大惡可以在任何一地生發。

“9·11事件”後,布什政府以反恐為名不斷加強警察化進程,削弱公民個人權利的立法衝動,已經在美國知識份子中引發了深刻擔憂。

“我感到美國的共和政體正處在我所經歷的最深重危機之中,”作家喬納森·謝爾(Jonathan Schell)對《紐約時報》說,“我們已經到了(極權主義)深淵的邊緣。”

字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大