字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/04/13 08:43:42瀏覽71|回應0|推薦0 | |

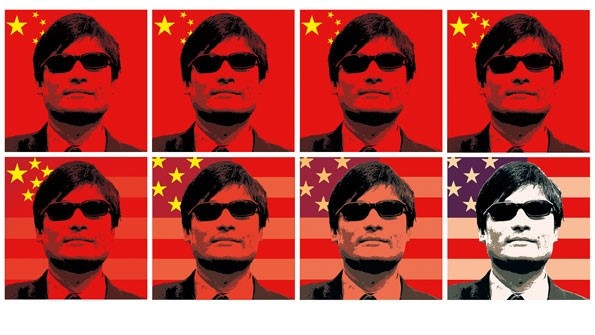

Human rights Blind justiceAn activist’s fate overshadows a vital relationshipMay 5th 2012 | BEIJING | from the print edition

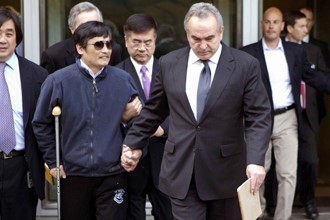

THE story of how Chen Guangcheng, a 40-year-old blind villager, escaped through the prison-like cordon surrounding his home and ended up hundreds of kilometres away in Beijing under American protection will long be recounted as one of the most dramatic episodes in America’s dealings with China over human rights. After six days at the American embassy, Mr Chen left on May 2nd for medical treatment, with an assurance from China that he would be safe. Within hours, Mr Chen was pleading for America to help him and his family leave the country. Mr Chen’s case became a huge and unexpected embarrassment for both countries just as they were preparing for their annual Strategic and Economic Dialogue, a two-day event in Beijing that began on May 3rd. Neither the American side, led by the secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, and the treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, nor even less the Chinese, wanted the talks to be soured by a squabble over the treatment of a rights activist. As both sides saw it, there were far bigger issues on the table, ranging from the possibility of an imminent nuclear test by North Korea to the fragility of the global economy. In this section · »Blind justice · At sea But as the talks began, a deal that the two sides appeared to have stitched together in frantic days of secret negotiations over Mr Chen was beginning to look ragged. The agreement, hailed by Mrs Clinton as reflecting “his choices and our values”, involvedMr Chen checking into a hospital (pictured above) for a foot injury sustained during his escape and being reunited there with his family. An American official said Mr Chen would be allowed to study at a university in China in a “safe environment”, implying that China had agreed to end years of relentless persecution. The official also said that China had agreed to investigate alleged abuses by the authorities in Mr Chen’s home province of Shandong. These appeared to be modest concessions as well as a sign of unusual willingness by China to negotiate with a foreign power over the welfare of one of its citizens—even if no guarantees were involved. In theory, Mr Chen and his family should be free to go anywhere in China and do as they please. No criminal charges or other legal restrictions are pending against them. (Their house arrest for the previous 19 months had been entirely illegal.) But the Chinese negotiators did appear to be saying that somehow they would protect Mr Chen from Shandong’s snatch squads. Local police in China frequently roam far beyond their jurisdictions, often without legal pretext, to seize citizens suspected of causing political embarrassment to their hometown governments. The authorities in Beijing had not previously hinted that officials in Shandong might have erred. Having gained admission to a Beijing hospital, however, an increasingly uneasy Mr Chen appeared to change his mind. In interviews with foreign journalists the activist and his wife spoke of a threat hanging over what had earlier seemed a joyful departure from the embassy. They said Chinese officials had previously given warning that unless Mr Chen left the American embassy, his family would be sent back to their village of Dongshigu in Shandong, more than 500km (310 miles) south-east of Beijing, where they had been confined since Mr Chen’s release at the end of a four-year jail term in 2010. A State Department spokeswoman said that “at no time” had any American official spoken to Mr Chen about physical or legal threats by China, nor had Chinese officials conveyed such threats to the Americans. But she did confirm that China had said the family would be returned to Shandong if Mr Chen stayed in the embassy. Given the family’s sufferings in Dongshigu, it is hardly surprising that Mr Chen now says he regarded this as a threat. From the hospital where he remained as The Economistwent to press, he has appealed through journalists for the Americans to help him and his family to leave the country. He told one that he would like to leave on Mrs Clinton’s plane. Mr Chen’s wife, Yuan Weijing, told The Economist, “The Americans did not do what they said they would do.” America’s ambassador to China, Gary Locke, insists Mr Chen was not pressured to leave the embassy. The request for more American assistance could foment a diplomatic crisis. China has already made its anger at America’s involvement in Mr Chen’s case very clear. After Mr Chen left the embassy, a foreign ministry spokesman accused the Americans of interfering in China’s internal affairs and demanded an apology. He said the embassy’s behaviour had been “utterly unacceptable” and called on America to “deal with” those responsible, apparently meaning diplomats who had helped Mr Chen. The spokesman also demanded a guarantee that there would be no such cases again. The Americans hope there will not be. One official described Mr Chen’s as an “extraordinary case involving exceptional circumstances”, which he said America did not expect to be repeated. Don’t go there Despite widespread complaints by Chinese people about human-rights abuses, there has only been one other known example of a prominent dissident being given protective custody by a foreign diplomatic mission in Communist-ruled China. That was in 1989, when Fang Lizhi, an astrophysicist accused by China of stirring up the Tiananmen Square unrest that year, was admitted with his wife to the American ambassador’s residence. Arrangements for their safe passage to America, where Mr Fang died last month, took more than a year. Since then Chinese dissidents have generally shunned the notion of seeking similar refuge, not least because of concerns that they might be labelled as pawns of the West. If Mr Chen and his family are able to persuade the Americans to use diplomatic muscle to get them out of the country, others might be tempted to try. And if America helps them, a relationship already marred by mistrust and occasional acrimony could turn into one perennially strained by squabbles over human rights. Mr Chen was the second prominent Chinese citizen to enter an American diplomatic mission for protection within three months. In February Wang Lijun, an official with the rank of deputy provincial governor, fled to the American consulate in the city of Chengdu. He walked out into central government custody a day later, reportedly of his own volition, having told the Americans about the murder of a British businessman allegedly involving the wife of Bo Xilai, the party chief of nearby Chongqing. Mr Bo has since been fired and his wife has been detained. Their case continues to roil Chinese politics.

President Barack Obama has faced some criticism at home for allegedly failing to do more to protect Mr Wang (a former police chief widely accused of riding roughshod over the law). Failing to help Mr Chen leave the country would give his opponents in an election year much more powerful ammunition. Unlike Mr Wang, Mr Chen is regarded by many Chinese, intellectuals and ordinary people alike, as a hero for his campaigning on behalf of victims of local injustice. The story of Mr Chen’s flight to the American embassy is likely to bolster public admiration for him, in China and abroad. Hu Jia, a Beijing-based activist who met Mr Chen after his escape, says that during the night of April 22nd Mr Chen climbed over the two-metre high concrete wall built by the government to seal off his house. (It was normally floodlit by his guards, who also jammed mobile-phone signals.) For some 20 hours, says Mr Hu, Mr Chen struggled on his own, falling down “more than 200 times” before meeting another activist who drove him to Beijing. Mr Hu says that a trembling Mr Chen held his hand and wept, repeating the words “brother, brother”, as the two men embraced for the first time in seven years. It was an extraordinary feat given the lengths that officials in his home prefecture of Linyi had gone to in order to silence him. Mr Chen had particularly angered the Linyi authorities by exposing forced sterilisations and abortions involving thousands of women in connection with China’s one-child policy. Officials deployed dozens of civilians to keep visitors away and the Chens in their home. Many who tried to reach the family, including diplomats and journalists, were roughly turned back. After a Hollywood actor, Christian Bale, was violently blocked from entering the village in December, a foreign ministry spokesman said Mr Bale should be “embarrassed” for his attempt to “create news”. It was clear the Linyi government’s behaviour enjoyed high-level backing. Where to now? Mr Chen’s fears of further persecution appear well justified. Many activists believe the central government’s security apparatus, led by a powerful member of the Politburo’s standing committee, Zhou Yongkang, has given active support to the Linyi authorities. After Mr Chen’s escape, several activists who helped him, including Mr Hu in Beijing, were taken in for questioning by police about how he achieved it. Since Mr Chen’s emergence from the embassy, others have reported tighter surveillance. Mr Zhou may have suffered a political setback with the purge of his ally, Mr Bo, in Chongqing. But he has retained a high profile. The treatment of other activists as well as the continued deployment of goons in Mr Chen’s village (Mr Chen said they tied his wife to a chair for two days after he fled) suggests little change of heart within the police force. It is likely that officials had no intention of giving Mr Chen completely free rein. China’s loosely worded state-security laws give them leeway to seize him should he be deemed a threat to the party. In November, after Mrs Clinton expressed concern about Mr Chen’s treatment, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman retorted that the Chinese government “protects the rights and interests of Chinese citizens”. But the thuggery in Mr Chen’s village continued unabated. from the print edition | China · Recommended Want more? Subscribe to The Economist and get the week's most relevant news and analysis.

筆者回文曾參考多方意見而寫 Blind justice May 6th 2012, 03:50

I first heard of Chen Guang-cheng’s thoughts from 2006’s Washington Post and Time Magazine when Chen got 4-year prison on “damaged property and disrupted traffic”. I remember the judgement was so strange because the cause of arrest, “a protest at inhumanely forced abortions and sterilizations”, didn’t accord with the judgement. Chen is the few Chinese activists who still abide by the law and principle of China’s Communist Party (CCP). It is only Tienanmen June-4th incident’s Wang Dang that can be talked with Chen because of their good brain.

Basically, most of dissidents - such as Fang Li-zhi, Liu Xiao-bo and Ai Wei-wei - cannot get any their so-called goal of “success”. Instead, the well-organized system is the key to know whether these dissidents really threaten CCP. Therefore, I have no idea of why Liu was qualified as Noble Laureate, and the reason why Ai gets widespread support. I have surfed Ai’s book in Taipei, but I just watch the geek “things” and murmur about his so-called thoughts. And Liu’s relative reports few appeared in newspaper (I just glanced at Washington Post once in 2009).

I don’t say that it is unacceptable or impractical for China to carry out the democratic reform or enjoy the freedom of public speech. I heard of sayings of so many so-called heroes, but their supporters just stayed under ideological condition while lacking of the persuasive contention. Having been living in Taipei for a long time, I support the figures in 1979’s Kaohsiung Incident, including Taiwan’s former outstanding President Chen Shui-bian. I have chatted with Tsaou Chun-ching, one of Chinese dissident, as well.

In reality and recently, both cross-Taiwan strait sides of government have some problem for weeks. On one hand, Hu Jing-tao and Wen Jia-bao sometimes loosen the control of local or provincial government so that fourth-generation CCP are less effeicient than third-generation Jiang Ze-min and Zhu Rong-ji. During Jiang’s tenure, there are few embarrassment except for Falun Gong. On the other hand, the unreasonably raising taxes of public water and electricity put Ma Ying-jeou on a collision course which results in the possible suspension from Hsieh Chung-ting’s (Frank Hsieh) rally. Besides, Chen Shui-bian suffers unreasonably quirky crime only to lead Ma to be stinky in Taiwan.

I never mean that there should be a brand-new nation building in China. In other words, I don’t think that this word “China” is equal to evil or devil concerned. Seemingly, there is some short-circuit. For several years, I work for the fifth-generation CCP, mainly Xi Jin-ping and Li Ke-qiang, who owns better well-organized proficiency and who will take Beijing’s power over from the fourth ones in less than one year. Xi and Li may continue political reform, which Wen once disclosed on CNN’s interview in 2010 for the first time. Basically, CCP is working hard on projects for clear law system and rational allocation. However, a regrettable fallacy still emerge in Chen’s case.

On May 3, Chinese Foreign Minister’s spokesman, Liu Wei-min, said that Chen can be seen as other Chinese citizen who enjoys the freedom of studying abroad. This statement infers a few compromise between CCP’s power and foreigner sounds. Moreover, Chen’s case may affect the thoughts and re-shuffle territory of CCP's political pedigree. As Li Ke-qiang told me several days ago, the governing team seems to concede defeat. Meanwhile, because Chen “sued” the officers for the corruption and “indicated” the improper judgement by local court according to his video’s sayings. Chen blatantly stated one sentence after another. Beijing’s authority, led by “vice-party secretary” Zhou Yong-kang, is impossible to have nothing to do with Chen’s affairs - whether Chen wants to go abroad or not. In reality with anger, Li and I never think that to practise house arrest can bring any advantage for China. Also, after I understand something about Chen’s surroundings of hometown, these policemen, or supervisors, indeed looks like Kuomintang’s “special man” during White horror, when social deprivation and corruption was everywhere. By logic, Chen has no choice but to leave for the safer location to appeal to Beijing’s core since Apr. 22 - although there is flaw in the process of party’s principle.

Afterwards, Chen is inclined to go to America rather than stay in China. On May 4th, New York University decided to invite Chen to be a visiting scholar. China is reluctant to make sino-American relationship return to the circumstance Tienanmen incident in the process of economic transformation. Therefore, Chen’s case may follow Fang Li-zhi’s in 1989. Fang had lived in US embassy for 13 months and then left for US by chance of US July-4th celebration under James Lilley’s control. Well, more bloggers raise the tone similar to Henry Miller’s “The blind lead the blind. It’s the democratic way.” And more echoes of Chen’s appeal for individual self-respect and fair expand in the near future.

Recommended 13 Report Permalink ---------------------------------------- 筆者第一次聽過陳光誠這位名字是和2006年8月24日的判決有關,在Washington Post 華盛頓郵報的報導中所看到他的事蹟一則,就是維護因一胎化政策受波及的婦女和弱勢團體主要是殘障同胞的權益。順帶一提,筆者每月會上華盛頓郵報的網站及相關主題蒐集,此後至今日筆者會在電腦資訊工程方面的重要指引,就是當時供應華郵科技新聞,作為其科技類伙伴PCWorld雜誌社來的(不是PC Magazine!)。筆者在陳先生跑到時任美國駐中大使Gary Locke駱家輝的美國大使館後,除了回文所提之外,補充一些:聽過一方面的前因後果的問題。是因為前一兩年時,在「政治檢查」的黨紀人員作被處以軟禁的「人員訪視」時,山東省黨組部出勤紀錄是全國各省市最後一名,有稍嚴重的紀錄問題,根本「答非所問」曾被提出討論,因此派在前一年因金融紀律位居所有行政官員課責首位(政績最好的那位)的郭述清先生任山東省委書記,曾經問過陳先生狀況,但一線人員沒有按照守則及上級要求處理,比如思想考核筆記不落實,而是用私刑,還是在一年內出了大問題。所以當時中共中央偏以大事化小的態度處理,就是認賠啦,很快的同意發護照給陳先生並且沉默。 當時聽過會比照李潔明發給方厲之夫婦護照的模式處理並不予評論,之後陳光誠便就在紐約大學當訪問學者,2013年曾經訪問台灣和時任民進黨代主席蘇貞昌及前副總統呂秀蓮公開會面。前年曾經在訪問日本時又公開呼籲各界推翻共產黨統治,備受爭議。其它方面就不在此延伸贅述。 這篇筆者辯護個問題就是當然一堆網友不會覺得溫家寶總理在CNN說的政治改革方案有任何進展,雖然路過閱讀者不少,就被轟個滿頭包來,另外這篇附近起的討論比起前幾月會更嚴謹,主要是東海南海軍事衝突問題、經濟發展、薄熙來案和陳光誠的事件發展。中國問題在本年三至五月成為國際間最大的討論問題。 --------------------------------------- *BBC中文網2012年4月27日: 陳光誠向溫家寶提三要求(錄音記錄) 圖片版權 online Image caption 陳光誠據稱目前在北京的一個安全地點遭中國當局軟禁的盲人維權律師陳光誠已被救出山東,到達安全地點。他周五(27日)在網上露面,通過視頻向總理溫家寶提出三點要求,希望溫家寶能徹查有關問題。 陳光誠這段視頻全長15分鐘10秒。以下是根據他的視頻講話完成的文字記錄稿。 敬愛的溫總理,好不容易我逃出來了,網上所有的流傳,以及對我實施暴行的指控,我作為當事人,在這裏向大家證明一下這都是事實,有些發生的比網上流傳的有過之而無不及。 溫總理,我正式向您提出如下三點要求:第一點,對這件事情您親自過問,指派調查組展開徹底調查實真相,對於是誰下命令,命令縣公安、黨政幹部 其它十人到我家裏入室搶打加傷害,而且不出示任何法律手續,沒有一個人穿制服,打傷了不讓就醫,誰做出的這樣的決定,要展開徹底調查,並依法作出處理,因 為這件事情實在太慘無人道了,有損我們黨的形像。 他們闖入我家裏,十幾個男人對我愛人大打出手,把我愛人摁在地上,用被子蒙起來,拳打腳踢長達數個小時,對我也同樣實施暴力毆打,像XX,像縣公安的很多人都認識,像XX,像XXX,像在我出獄前後多次打我愛人的XXX,XXX,XXX等這些人員要做出嚴肅處理,還有一個姓X的我不知道名字,我以當事人的身份對所有這些違法犯罪的人作出如下指證。 他們在入室搶打的過程中,像XX他是我們雙戶鎮,分管政法的副書記,多次揚言說「我們就是不用管法律,就是不用管法律怎麼規定的,不用任何法律手續,你能怎麼著?」,他多次帶人到我家裏去對我家 實施搶劫,對我家裏人實施毆打,像XXX是在我們那長期領著20多個人對我實施非法拘禁的,他是第一組長,這個人對我愛人多次實施毆打,曾經追到半道把我 愛人從車上拖下來實施毆打,而且對我母親也是大打出手,兇惡無比! 還有像XXX,在去年的18號下午把我愛人打倒在地,他是我們鄉鎮的司法所的工作人員或 所長,當時把我愛人的左臂嚴重打傷,在我們村口打貝爾那個人據我所知叫XXX,就是網民所說的軍大衣,他在去年的2月份還像CNN扔過石頭,就是他,沒 錯!這個我知道的! 我聽說還有很多網民被很多女看守打,當時我還不知道雇女看守,後來我一了解才知道,這些所謂的女匪都是從各村調來婦女主任,也有是這些 組長們的親戚,但絕大部分都是婦女主任們構成,還有像XXX,還有很多不知名的人員,但我知道他們都是公安系統,雖然他們不穿任何制服,雖然他們沒有任何 法律手續,但他們自己竟然揚言說我們現在不是公安,我問他們是什麼,他們說我們現在是黨教我們來為黨辦事的,這我就不詳細說了,他頂多是為黨內某一個不法幹部辦事的。 從各方面信息顯示,除了這些鄉鎮幹部每個組裏8個人以外,最少的時候也每個組過來20多個人,他們一個3個組,七八十人,那麼在今年在善良的 網友不斷的猜測關注下,最多的時候他們達幾百人,對我們實施整體的封鎖,大體的結構就是以我家為中心,然後我家裏有一個組,我家外面一個組,家外面一個組 就是分散在我家周圍,四個角上,路上,再往外就是以我家為中心,所有的路口都有人,從我家向四面八方不斷的分散開來,一直到村口,最嚴重的時候一直到鄰村,在鄰村的橋上,也坐著七八個人。 然後這些不法幹部,利用手中權力,命令鄰村的幹部在那陪著,然後還有過來的一批人開著車不斷的巡邏,在巡邏的範圍可達我村以外5公里甚至還要多,那這樣的層層的看守,在我村裏最少有七八層,而且把我們村周圍所有進村的路口都編上號,據我所知我這編成28號路,到時候他們上班的時候,誰誰到28號路,真是三步一崗、五步一哨,草木皆兵啊,據我所知,參與對我實施迫害的光縣公安、刑警,以及縣、雙後鎮黨鎮幹部就有 90-100人左右,他們數次對我實施非法的迫害,要求展開徹底的調查。 我雖然自由了,但我的擔心隨之而來,因為我的家人、我的母親、我 的愛人、我的孩子還在他們魔爪之中,長期以來他們一直對他們實施這種迫害,可能因為我的離開,他們會對他們實施瘋狂的報復,這種報復可能會更加的肆無忌 彈,我愛人左眼的髖骨曾經被他們打的骨折了,到現在還能摸得出來,腰部被他們蒙著棉被被他們拳打腳踢,到現在為止很明顯的突起,左側第十第十二肋明顯還能摸到上面有疙瘩,而且慘無人道的不讓就醫。 做為老母親,在生日那天,被一個鄉鎮的黨員幹部,掐著胳膊推倒在地,仰面朝天,頭撞在東屋的門上,害得母親大哭一場,而且母親在向他們指揮說「仗著你們年輕,你們行……」,這些人還恬不知恥的說「對啊, 年輕行這是真事啊,你老了就是打不過我」,何等的無恥,何等的慘無人道,何等的天理不容啊!!! 對我幾歲的孩子,每天上學都三個人跟著,每天都要進行搜 查,對所有的書包裏的東西拿出來,書本挨頁去翻,在學校裏看著也不讓出門,一回家就關在家裏不讓出大門!還有就是我整個家的處境,從去年7月29號斷電一 直到12月14號才給恢復,從去年2月份不讓我進出買菜,讓我們生活極度困難,所以我對此非常感謝網友不斷的關注,加大關注力度,以了解他們的安全情況, 以了解他們中國政府本著法律尊嚴,維護人民利益的角度去保證我們家人的安全,否則他們的安全沒有保障,如果我的家人出任何的問題,我都會持續的追討下 去!!! 那麼第三點,大家可能會有一些疑問,為什麼這些事情持續了數年始終沒能解決呢,地方上,不管是決策者還是執行者,他們根本不想解 決這個問題,作為決策者是怕自己罪行暴露所以不想解決,而作為執行者,這裏面有大量的腐敗,我記得(去年)八月份,他們在對我進行文革式的批斗的時候,曾 經說「你還在視頻裏說花了三千多萬,你知不知道這三千多萬是08年的數字了,現在兩個三千多萬都不止了,你知道吧?就這還不包括到北京到上層賄賂官員的錢!你有本事你在網絡上說吧!」他們當時曾經說過這樣的事情,還有很多過來人說「我們才拿多少點錢,大頭都讓人家給剝盡了」這的確是他們發財的一個很好的機會。 據我所知,鄉里剝掉的錢都到組長的手裏,每雇一個人一天是100塊錢,那麼這些組長再去找人的時候,就明確的告訴他,說是一天100塊錢的工資,但我一天只給你90,那10塊是我的,那麼在當地每天勞動一天也只有五六十塊錢,做這樣的事情又不需要付出很大的勞動,又很安全,又一天三頓管著吃,他們當 然都願意幹,90塊錢也願意幹,可是這一個組20多個人對組長來講一天就是200多塊的收入,那這個腐敗是何等的厲害!另外據我所知,我在被關押期間 (***沒聽清楚),他們的組長就在家裏把土地拿出來(應該是光誠家的土地)全部種上菜,然後種點食用菜的時候,他們自己買自己賣、謀取利益,這些事情民 眾都知道,一點兒沒有辦法。 據我所知,維穩經費,他們有一次告訴我,縣裏一次性就能給鄉里撥幾百萬,而且他們說「我們能拿多少點,大頭都 讓人家拿了,我們頂多就喝點湯」。可見這裏面的腐敗是何等的嚴峻,這種金錢、權利是何等的被亂用,因此對這種腐敗行為要求溫總理調查處理,我們老百姓納稅 的錢不能就這樣白白的讓地方的不法幹部拿去害人,去害我們黨的形像,他在做這些所有的見不得人的事情的時候,都是打著黨的旗號在做的,都說黨讓你做的! 溫總理,這一切不法的行為,很多人都不解,究竟是地方黨委幹部違法亂紀、胡作非為、還是受中央指使?我想不久就應該給民眾一個明確的答覆,如果咱們對此展開徹查,把事實真相告訴公眾,那麼,其結果是不言而喻的,如果您繼續這樣不理不睬,你想民眾會怎麼想? 有參考的經濟學人文章及一篇中國海外華人媒體文章均予以列在後面 *第一篇相當於快訊JUST-IN的雜誌編輯貼文: Chen Guangcheng slips loose Postcard from an undisclosed locationApr 27th 2012, 12:02 by T.P. | BEIJING THE lawyer and rights-activist Chen Guangcheng has apparently escaped from the extra-legal house arrest under which he has been held since September 2010, effectively imprisoning him in his hometown in rural Shandong province. At this point his physical whereabouts are unknown, but on Friday he emerged on the internet, in the form of a bold video appeal to China’s premier, Wen Jiabao. “Dear Premier Wen. With great difficulty, I have escaped,” Mr Chen said at the beginning of his 15-minute statement. In a polite but assertive tone, Mr Chen went on to make three specific demands: stern punishment for the local officials who, he said, have illegally tormented him and his family; an assurance of safety for his relatives; and a broad effort on the part of the government to rein in corruption. Other rights activists, both in China and abroad, tell reporters that they have spoken to Mr Chen since his escape. They say he slipped away from his heavily guarded home, outside the city of Linyi, on Sunday—and that he has left Shandong. Some reports have suggested that he may have found refuge in a foreign diplomatic mission in Beijing, but this could not be confirmed. Blind since childhood, Mr Chen educated himself in the law. Early in his career he earned official praise for his work on behalf of disabled people living in rural districts. Later he antagonised the authorities by advocating on behalf of clients who claimed they were forced into having abortions or sterilisation procedures, in the service of China’s strict population-control policy. In 2006, Mr Chen was convicted on vague charges of damaging property and disrupting traffic. He served a 51-month sentence after which he was confined to his home and kept under heavy guard, with what seems to have been no legal justification whatsoever. He has attracted admiring attention ever since. Many ordinary Chinese have sought to demonstrate their support by trying to visit him. Foreigners have done likewise, including diplomats, journalists and entertainers. In most cases Mr Chen’s would-be visitors have been turned away crudely; in some cases, violently. According to Human Rights in China, a pressure group based in America, Mr Chen’s older brother and nephew went missing after authorities discovered his escape. The episode has the potential to embarrass some officials acutely, at both the local level where they failed to stop Mr Chen’s escape, and at the central level. China’s top leaders seldom suffer the indignity of having demands put to them in such public and adversarial fashion. 而Human Rights in China 聯結那篇如下: https://www.hrichina.org/en/content/5991 Blind Lawyer Chen Guangcheng Reported Missing, Brother Taken Away, Nephew Fears for His Own LifeCase Update 2012-04-26 According to Chen Kegui (陈克贵), a nephew of blind rights defense lawyer Chen Guangcheng (陈光诚), who has been under house arrest since September 2010, is now missing from his home. Chen Kegui also told Human Rights in China (HRIC) that Chen Guangfu (陈光福)– Chen Kegui’s father and Chen Guangcheng’s older brother – had been taken away sometime in the late evening of April 26. He does not know who took his father as he did not witness it occur. Chen reported that on April 26, his mother overheard one of the guards watching Chen Guangcheng’s home say on the phone, “Chen Guangcheng is no longer here.” Chen Guangcheng’s home is about 200 meters from Chen Kegui and his parents’ home in Dongshigu Village, Shuanghou Township, Linyi, Shangdong Province. Chen Kegui said that in the early morning of April 27, he was awoken by footsteps outside his home and heard his mother shouting, “What do you want?” He grabbed two kitchen knives for self-defense. Then he saw several people in his front yard, including Shuanghou Township head Zhang Jian (张健)who is in charge of enforcing his uncle’s house arrest. When Zhang saw Chen Kegui holding the knives, he ordered the men to beat Chen with wooden sticks, so Chen fought back in self-defense. He did not know how many people he injured, but said that all of the men fled. He then called the police to report the incident, but no police showed up. Chen said that he is now in hiding and fears that Zhang Jian will return to kill him. Chen Guangcheng’s case has attracted wide international attention. He was imprisoned for four years and three months after he helped villagers resist forced abortions. After his release in September 2010, he and his wife, Yuan Weijing (袁伟静), were forbidden to leave their home. The couple subsequently detailed their experiences and abuses under house arrest on videotapes that were distributed on the Internet in February 2011. They were reportedly subjected to even harsher treatment afterwards. In December 2011, American actor Christian Bale was punched by men guarding the village when he tried to visit Chen. Chen GuangchengThe great escapeMay 2nd 2012, 12:26 by J.M. | BEIJING THE STORY of how Chen Guangcheng, a 40-year-old blind villager, escaped through the prison-like security cordon surrounding his home and ended up hundreds of miles away in Beijing under American diplomatic protection will long be recounted as one of the most dramatic episodes in America’s dealings with China over human rights. After six days at the American Embassy, Mr Chen left “of his own accord”, the two governments said, to receive medical treatment in a Beijing hospital. Mr Chen will stay in China and be allowed to attend university. Despite ubiquitous complaints by Chinese about human-rights abuses, there has only been one other known example of a dissident being granted protective custody by a foreign diplomatic mission in Communist-ruled China. That was in 1989, when Fang Lizhi, an astrophysicist accused by China of stirring up the Tiananmen Square unrest that year, was admitted with his wife to the American ambassador’s residence. Arrangements for their safe passage to America, where Mr Fang died last month, took more than a year. China is now a much stronger country and America far more anxious not to displease it. The announcement on May 2nd that Mr Chen had left the embassy (he checked into a hospital, accompanied by America’s ambassador, Gary Locke) appeared to signal at least a temporary compromise. But China also demanded an apology from America for taking Mr Chen into the embassy and gave no public guarantee of his safety. Both countries were anxious that Mr Chen’s flight should not spoil their annual high-level “strategic and economic dialogue”, a two-day event which began in Beijing on May 3rd as The Economistwent to press. They are being led on the American side by the secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, and the treasury secretary, Timothy Geithner, neither of whom want a human-rights case to overshadow discussions about issues ranging from a possibly imminent nuclear test by North Korea to global economic rebalancing. The timing was especially bad for China, which was already under enormous political stress following the flight of a senior provincial official to an American consulate in Chengdu in February and the dismissal it led to of a Politburo member, Bo Xilai. Mr Chen’s journey began in the village of Dongshigu in Shandong Province, more than 500 km (300 miles) south-east of Beijing, where he had been kept under house arrest since his release at the end of a four-year jail term in 2010. Local officials have long been determined to silence Mr Chen, a self-taught legal worker who became widely known for championing victims of local injustice. Mr Chen particularly angered the authorities by exposing forced sterilisations and abortions involving thousands of women in connection with China’s one-child policy. No legal basis was ever produced for keeping Mr Chen confined to his home, nor for deploying dozens of thugs to keep visitors away, sometimes with violence. The goons appeared to enjoy backing from at least some leaders in Beijing. Hu Jia, a Beijing-based activist who met Mr Chen after his escape, says that during the night Mr Chen climbed over the two-metre high concrete wall built by the government to seal off his house. (The house was normally floodlit by his guards, who also jammed mobile-phone signals.) For some 20 hours, says Mr Hu, Mr Chen struggled on his own, navigating “eight lines of defence” and falling down “more than 200 times” before meeting another activist, He Peirong, who drove him to Beijing. Mr Hu says that Mr Chen wept and said repeatedly, “brother, brother”, as the two men embraced for the first time in seven years. Mr Chen’s hand trembled constantly as it gripped Mr Hu’s. Mr Chen’s problems were not yet over, however. Before he was finally delivered into American protection Mr Chen was followed in Beijing by what appeared to be secret police. Mr Hu says he does not know whether the police were aware they were tailing Mr Chen, or whether they were merely conducting routine surveillance of his dissident escort. Both countries kept quiet about Mr Chen’s escape and his sojourn at the embassy until after he left. China then made its anger clear, accusing America of interfering in China’s internal affairs. It said this was “utterly unacceptable” and called on America to “deal with” those responsible, apparently meaning diplomats who helped him. Some of this could be posturing, aimed at defusing criticism of the leadership by hardliners resentful of any kind of negotiation with America over the fate of a Chinese citizen. Hardliners are a powerful force in China’s security apparatus. Since Mr Chen’s flight, several activists who helped or met Mr Chen after his escape, including Mr Hu, have been called in by police in Beijing and elsewhere for interrogations about how he achieved the feat. Ms He, who drove him to Beijing, remains missing. Mr Chen’s wife and two children have been escorted by officials to join him in Beijing. But even if America has secured a way of ensuring their safety, others like them can still expect short shrift. Chen GuangchengChen, China and AmericaThe disputed story of a blind activist raises difficult questions for both superpowersMay 5th 2012 | from the print edition

AT RARE moments the future of a nation, even one teeming with 1.3 billion souls, can be bound up in the fate of a single person. Just possibly China is living through one of those moments and Chen Guangcheng is that person. A blind activist from Shandong province, Mr Chen emerged from poverty, fought for justice and paid the price with his own liberty. Last month he made a bid for freedom and became ensnared in the impersonal machinery of superpower politics. What now befalls him and his family raises questions about Sino-American relations and the character of Chinese power. In many ways, Mr Chen is the best of modern China. Blind since childhood, poorly educated until adulthood and then self-taught, he became a lawyer, never a safe career in a country where might is right. As a peasant activist fighting local battles—which makes him a much more potent force in China than politicised members of the urban elite such as the artist Ai Weiwei (see article)—he was praised for years by the local government for advocating the rights of disabled people. Then he crossed the line by taking on the local party over the abortions and sterilisations it enforced as part of China’s strict one-child policy. After four years in jail on spurious charges, Mr Chen was kept prisoner in his own home for 19 months. In this section · »Chen, China and America On April 22nd he fled to the American embassy in Beijing, where Hillary Clinton, America’s secretary of state, was due to arrive for her country’s annual Strategic and Economic Dialogue with China. What happened next is disputed (see article). American diplomats say they became close to Mr Chen, even holding his hand when they spoke. They say that, after six days inside, Mr Chen willingly left the embassy for hospital, accompanied by the ambassador, to be reunited with his family. He had received assurances from the Chinese government that he would be treated well and allowed to study law at university. However, from his hospital bed, a weary, browbeaten Mr Chen suddenly began to complain that American diplomats had “lobbied” him to leave, that they had not let him confer with his friends and that Chinese officials had threatened his wife. He was “very disappointed” in the American government and said he wanted to leave China. For their part, Chinese officials acknowledge no deal—but they have sternly demanded an apology from America. The Beijing switch With luck the dispute will calm down. Perhaps Mr Chen will be spirited away to America, or find a way to live normally in China. But the incident raises three questions. Most immediately, did America’s best diplomats let a brave man down? With Mr Chen out of their care, they now have little bargaining power. If they were duped by their Chinese counterparts, or too ready to accept their assurances, they will be taken as fools. If they struck a deal in haste, calculating that currencies and tariffs should eclipse the rights of an inconvenient blind man, they will be taken as knaves. Mrs Clinton boasted that Mr Chen left the embassy “in a way that reflected his choices and our values”. Her words will undoubtedly be scrutinised in this year’s election. Yet the plight of Mr Chen raises two deeper questions about his own country. The first is whether China still feels it must put its relations with America before anything else. In past disputes, notably the aerial collision of a Chinese fighter and an American spyplane in 2001, China has tended eventually to put America first—as the source of trade and wealth and the policeman for the global commons. But China is stronger now, its economy is bigger, it can defend its own shores and it expects to carry weight in the world—especially as, in the view of some triumphalists in Beijing, America has been dragged down by the financial crash and its vicious partisan politics. If Mr Chen is now punished and Barack Obama is humiliated, that will signal a troubling shift in the terms of the superpowers’ relations. A wounded, suspicious America and a rampant China, bent on winning the respect it thinks its due, set the stage for dysfunction at best and conflict at worst. It would be a terrible outcome for both superpowers and for the world. They should strive to patch things up. The power shift The other question—and one that will preoccupy China in a year when power shifts to the next generation of leaders—is how the country is run. The blind lawyer in dark glasses is just one of millions of ordinary people smarting under arbitrary rule. For a long time—first when China shed Maoism and then as its economy surged—most Chinese people cared less about the niceties of the law than their fast-rising living standards. Even then the weak, the disabled, the unemployed and the poor were ignored, sidelined and sometimes trampled in the rush for wealth. Now, a slowing economy, corruption, rural anger and urban freedoms all mean that the party isunder pressure to enforce the rule of law—especially in order to curtail the impunity of local officials. The Communist Party recognises that it must start to be more accountable and give people a legal outlet for their grievances. Faced with an insurrection in Wukan, after villagers protested about local officials’ profiteering from the sale of land, Beijing ended up siding with the villagers. The party has been keen to depict the sacking of Bo Xilai, who ran the south-western region of Chongqing, as proof that China is a country of laws. Wen Jiabao, China’s prime minister, has argued that corruption will not be tolerated. Try as it might, the party cannot altogether control the country’s 250m microbloggers who follow each drama live and continue to confound the censors. The dilemma is that although the party needs the law to govern, it cannot submit to the law without losing power and giving up privileges. At the moment the party still wants to have it both ways. More than any other incident so far, the disturbing case of Mr Chen raises doubts about whether it can. It is a heavy burden to be resting on the frail shoulders of a man lying in a Beijing hospital bed as the diplomats and politicians dine together a few blocks away. But it matters enormously to China’s future. from the print edition | Leaders Chen GuangchengA pat on our backMay 6th 2012, 0:05 by M.S.

JUST up the street from me at the moment, on the corner of the Bernauerstrasse, is a massive photo-mural depicting the same street corner on an August day in 1961: a snapshot of Hans Conrad Schumann, an East German soldier, hurdling the barbed wire on top of the still-under-construction Berlin Wall to get to the West, and freedom. In those days, the stakes that led communist regimes to construct obstacles to emigration were clear: they were afraid that combined envy of the West's prosperity and, to a lesser extent, its intellectual and religious freedom would lead huge masses of their citizens to flee abroad. That, obviously, is not an anxiety that affects today's Chinese Communist regime. The fact that China does not fear that any sign of openness will lead large numbers of its citizens to emigrate is one background factor behind Beijing's apparent willingness to reach a face-saving agreement to allow dissident lawyer Chen Guangcheng to apply to "study" in the United States. The thing that has surprised me from the beginning of the drama is that it could possibly take place. We still don't know how Mr Chen managed to get from his village to the American embassy, but it seems extraordinary that the Chinese could have allowed a high-profile dissident to escape, could have lost track of him after his escape, or could have allowed him to approach the embassy to ask for asylum. On a couple of occasions during the time I spent in Vietnam, dissidents made surprise, unauthorised contact with American personnel at the embassy or ambassador's residence, but secret police stationed on the street nearby intervened extremely rapidly. In general, police seemed to know beforehand when dissidents were likely to stage such moves. That knowledge turned the relationship between dissidents, the regime, and the US government into a sort of choreographed dance, with limits drawn and signals sent based on mutual interest in avoiding embarrassment over declared positions. So it's not surprising that the result of the Chen Guangcheng drama looks likely to be one that allows America to maintain it has been true to its commitment to defending freedom of conscience, and also allows China to maintain it has not allowed Mr Chen to flee and claim political asylum. That's not that different from the way things operated in the old days. The relationship between communist states and America around dissidents has always been a bit of a dance. What's changed is that America's interest in protecting dissidents is no longer a matter of either economic or strategic self-interest. China is not a military foe, or an enemy of capitalism; it's our largest trading partner. And now I'm going to go out on a limb and say something rather gushy and perhaps obnoxiously self-congratulatory: The fact that China is not our enemy makes our continued commitment to defending freedom of conscience for Chinese citizens all the more laudable. We really have nothing to gain from protecting Chen Guangcheng, except that it lets us give ourselves a pat on the back and walk down the street feeling all free and democratic. So let's! Sure, as William Dobson points out, China is probably just as interested in getting rid of Mr Chen as we are in protecting him. And sure, immigrants these days tend to come more because they're tired, poor and hungry than because they're yearning to breathe free, and Chinese citizens these days are less interested in coming to America precisely because the path to middle-class security probably leads through Guangdong rather than Los Angeles. Still, when that rare individual comes along who really considers the freedom thing more important than the wealth thing, we apparently still feel honour-bound to do something for him. And that's a nice thing. (Photo credit: AFP) *補充:陳光誠妻子袁偉靜致胡溫二人求助信。原文引自阿波羅新聞網http://tw.aboluowang.com/2007/1123/64434.html

Bo Xilai v Chen GuangchengWho is the mightier?May 16th 2012, 9:54 by R.G.

THE two biggest personality-driven stories of the season, those swirling around Bo Xilai of the Politburo and Chen Guangcheng of Dongshigu village, have provided not only two extraordinary tranches of grist for the journalism-mill but also two very different sorts of vision for the future of China. Whose story matters more? Bo Xilai, in a man, represents the nexus of power and wealth that runs contemporary China. He was the high-flying princeling, a son of one of Chairman Mao’s revolutionary comrades, who hoped to become one of the top nine figures at the Communist Party Congress to be held this autumn. Now he has been purged from officialdom, his wife detained in connection with the alleged murder of a British businessman, and he himself stands likely to be prosecuted. In many respects Chen Guangcheng can be seen as his polar opposite. Born into a poor rural family, blind since childhood, Mr Chen is a self-taught lawyer who has spent years trying to represent the interests of poor peasants in his native Shandong province. He is one of hundreds of millions born to Chinese farms, without privilege of any kind, whose hope of a better life is driving them to fight for their rights. For the past three decades (and, arguably, for three millennia before that), the likes of Mr Bo mattered most. Though they have stayed largely anonymous, in their dark, boring suits and with their interchangeable titles, the revolutionaries and engineers behind the controls of the People’s Republic have built an extraordinary engine for growth, enough to persuade much of the world that China’s rise was inevitable. China’s leaders have indeed done amazing things for the country economically. Never mind that Mr Bo’s leadership in Chongqing appeared to present a different economic and social model—with its emphasis on the state’s involvement in the economy, a return to socialist moralising and a dash of populist personal style. In fact it exemplified the time-honoured way of Chinese imperial power: rule from the top down. But China is changing in a fundamental way. The story illustrated by Mr Chen, in his unwillingness to give up fighting for the little guy, his perseverance in the face of insuperable top-down power, represents the many forces that are now pushing up from the bottom. Blind men who teach themselves the law and then take on the Communist Party are still rare. But workers in factories seeking greater representation are not. And neither are house-church Christians pushing for more religious freedom. When the villagers of Wukan succeeded in ousting their corrupt local officials last year theirs, was just one of countless battles fought across the countryside. Peasants are becoming ever more willing to challenge corruption and poor governance. Wukan was not alone in persuading the party to listen, and back down. The new middle classes too, while still not wanting to rock the boat too much—they have benefited from the current set-up after all—are anxious to have their voices heard. Economists who analyse the link between economic development and political change note that few non-oil producing countries manage to sustain one-party rule once GDP per person passes $6,000 in terms of purchasing-power parity (PPP). The IMF says Chinese GDP per person is now more than $8,300 by PPP. Many of those new middle classes are looking for an independent legal framework to protect their newly-earned property and wealth. They too will take to the streets in protest, on issues such as pollution (eg, for the closure of a petrochemical plant in Dalian last year) and public safety (eg, in the case of the Wenzhou rail crash last year—and against the attempts to cover it up). The middle classes have long had something to say and now, in the form of the Twitter-like microblogs known as weibo, they have a platform to say it. Cracks are appearing even in the façade of the Communist Party’s control over the media. After four major newspapers ran an editorial strongly condemning Chen Guangcheng’s flight to the American embassy in April, the microblog of one of them, the Beijing News, posted a late-night tweet with the photo of a sad clown beside the words “In the deep still of night, we take off our mask of insincerity, and say to our true selves, ‘we are sorry’.” More criticism on the popular microblogs was levelled at the papers that ran the editorial than at Mr Chen himself. Despite all this, top-down power is still the deciding factor in China; the 18th Party Congress will be crucially important for the country’s future. With Mr Bo out of the way, it will probably look like a smooth transition of power to the “fifth generation” of Communist Party leaders, allowing for nervousness among Mr Bo’s erstwhile allies, and the usual horsetrading. But that smooth pliability does not go all the way down to the grass-roots. While the party can still imprison men like Mr Chen at will, it cannot squash the sense of engagement that comes naturally to a more mobile, prosperous and wired society. As the costs of success—financial, social and environmental—become clearer, and the fault lines beneath China’s rise are exposed, people like Mr Chen are starting to propel China’s future from the bottom up in a way that has never before happened. That is why his case (if only as an emblem, for now) says more about China’s future than Mr Bo’s. Those who might wish to change their country, though, must contend not just with the Communist Party’s brute force, such as subdues people in Mr Chen’s role. They must also find a way to grapple with the vested interests of those who profit so handsomely from the Party’s current state. It is hard to verify whether reports of Mr Bo and his family’s wealth are exaggerated. What is clear is that Chinese political leaders at all levels use their power to become extremely wealthy, and have created a sort of comprador class that will be very hard to challenge. Mr Bo played the game, lost and has been swept aside. But there are many more families like his among the princelings, the army and the heads of state-owned enterprises. They are well-entrenched, integrated parts of a regime that has no interest in letting go. They stand on a collision course with the pressures pushing from the bottom up. For 20 years, it has been more dangerous for the Communist Party to start political reform than it has been to put it off. The tipping point, when the reverse becomes true, may be at hand. Mr Chen would symbolise that shift. China has made extraordinary progress and does not always receive the credit it deserves for it from its watchers in the West. But the time has come now for leaders to lay out their vision for the next ten years. Their vision for China needs to be about more than roads and buildings and high-speed railways; it needs to concentrate more on people. Inherent tensions are starting to throw the inevitability of China’s rise into question. For all their success in building an increasingly modern country, China’s leaders have no broader vision for what they want their country and its people to be. Chen Guangcheng is just one peasant-activist. He may never have intended to get involved with high politics. It is no small irony that, when it comes to defining a society in which the government obeys the laws and individuals’ lives are to be respected, it is the blind man who has the clearest vision.

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |