字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

||

| 2018/05/05 23:01:59瀏覽237|回應0|推薦0 | ||

Tiananmen after 23 years Unfair and unjust things Jun 5th 2012, 5:32 by T.P. | BEIJING

I WAS in Beijing on June 4th 1989, when the People’s Liberation Army stormed into the city to end student-led demonstrations. They used tanks and automatic weapons and left many dead. And I have lived here ever since. Like most foreign reporters, in the years that followed I marked each June 4th anniversary with a story about how people remembered the bloody denouement that ended those weeks of tumult, mass protest and high political drama; about how, in subtle ways, they sought to commemorate those events publicly; and about how, in not-so-subtle ways, the government sought to stop them. In 1996, I started thinking that observance of the June 4th anniversary story was no longer obligatory. It was a remark made by a student I interviewed at Beijing University, one of the key incubators of the 1989 protest movement, that changed my mind. “We have other things to worry about. I need to concentrate on my studies and think about where I will be seven years from now, not about what happened seven years ago,” she said. Since that time, the approach and passage of the anniversary has generally been less fraught and less tense. Round-number anniversaries in 1999 and 2009 attracted more attention, and the event has always been commemorated with vigils in Hong Kong. And of course a relentless core group of mainland activists has persisted in their underdog’s campaign for remembrance, accountability and redress. Foremost among these are the Tiananmen Mothers, a group of relatives of those who were injured or killed in the 1989 crackdown. But to a surprising degree, the official campaign to shove 1989 down the memory hole has succeeded. Through their near-monopoly control of the media and educational materials, and their intimidation and suppression of those who would challenge the official version of events, authorities have made the story fade, faster than its advancing years would seem to allow. So far as I have gauged it, I’ve found the forced forgetfulness to be distressing. With this year’s anniversary however comes evidence that the ministers of propaganda have not succeeded in making “6-4” disappear entirely. Though it has not been one of those attention-getting round-numbered ones, the 23rd anniversary has seen an uptick in June 4th-related news and remembrance. The Hong Kong vigil attracted scores of thousands, and smaller-scale attempts to commemorate the killings were mounted (and quickly broken up) in cities on the mainland. For days leading up to the anniversary, internet-speeds slowed as filtering and monitoring were stepped up. The police presence was heavy not only in Tiananmen square itself, but also farther afield. I passed through two police checkpoints on Sunday, while driving back to Beijing from neighbouring Tianjin. I also saw police nervously standing guard by a crowd that had gathered around some street musicians on Monday—some 15km away from Tiananmen. In one especially bizarre episode, yesterday officials blocked internet searches on the term “Shanghai Composite Index”. As it happened, China’s leading stock exchange had reported a drop of 64.89 points for the day. The odd correlation of those digits, to June 4th, 1989 (ie “6/4/89”) surely marks a wild coincidence, if not an instance of extremely clever caper. Those who think it was mischief point out that the index was reported to have opened for the day at 2346.98, an improbable-seeming combination of all the day’s most sensitive digits. In a more solemn development, in late May the Tiananmen Mothers announced that one of its members, a 73-year-old man named Ya Weilin, had hanged himself in an underground car park. He died in despair over the lack of redress for death of his 22-year-old son, Ya Aiguo, who was shot in 1989. According to the group, the elder Mr Ya was a retired government employee in good health who “ended his life in such a resolute way to protest the government’s brutality.” And on June 1st one of the key officials who had been in power during the events of 1989 went public with a drastic rewrite of the story. Chen Xitong was mayor of Beijing at the time and, as much as anyone, became the public face of the official argument: that the protests were the result of a counter-revolutionary conspiracy orchestrated by a few foreign-backed “black hands”; and the government’s response was correct and unavoidable. Mr Chen was removed from power in 1995 in a spectacular corruption scandal, having nothing to do with Tiananmen in 1989. In a new book published in Hong Kong he says that June 4th was a tragedy that could have and should have been avoided. While he acknowledges that it was handled improperly, he says that he had little to do with the decision-making. Less than one month after the violence, he had been the one to read aloud the government’s report. In these newly published interviews he insists that every word of that statement—indeed every mark of punctuation—was written by others, and that he had no choice but to read it. The explanation for this year’s somewhat tetchier-than-usual observance of the June 4th anniversary may well be connected to the sort of elite-level political discord that is on display in Mr Chen’s interviews. He now appears to confirm what had seemed obvious at the time: that the turbulence on the streets of Beijing was tied to turbulence in the corridors of power. Events, Mr Chen said, “stemmed from the internal struggle at the top level and led to a tragedy nobody wanted to see.” As for today, Mr Chen points to continued divisions within the highest leadership over the history of 1989. His account is of course highly self-serving and impossible to verify. Even so, intimations of this sort must be especially unwelcome to his colleagues now. China is poised for its once-a-decade leadership transition later this year, and the boat has already been rocked by the spectacular fall from grace of Bo Xilai. Mr Bo had been a top contender for a spot in the new leadership but now finds himself in political and legal limbo, with a wife accused of murder and a senior deputy suspected of having made a desperate, treasonous dash to an American consulate. Further infighting over the history of Tiananmen would seem to be the last thing party leaders want to grapple with. But if Mr Chen is to be believed, they shall have to sooner or later. It “is only a matter of time” before the government declassifies information about 1989, and provides a clearer account of the roles played by different leaders, he predicts. “Unfair and unjust things will be readdressed one day,” in his words. (Picture credit: AFP) Remembering TiananmenResolute to the endThe 23rd anniversary of the massacre brings some unusual commemorationsJun 9th 2012 | BEIJING | from the print edition CHINA’S government dislikes discussing the protests in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and their violent end. But, when forced, it is quick to repeat its line of 23 years: counter-revolutionary “black hands” caused turmoil, and troops took resolute action to end it, paving the way for China’s subsequent advances. Each year the topic comes up around June 4th, the day in 1989 when that resolute—and bloody—action occurred. Each year, authorities play cat and mouse with anyone challenging its line. So too this year. Security was beefed up, as were controls on the internet, where most attempts at remembrance now occur. Banned search terms included obvious ones like “June 4th” (or “6.4.89”), but also less likely ones, including “Shanghai composite index”. In a strange coincidence (or a brazen stunt by a hacker) the Shanghai stock index reported an opening figure of 2346.98 on June 4th, and fell by 64.89 points during the day. Both figures include combinations of the forbidden digits, with the larger one including the number of years since 1989. In this section Hong Kong, as usual, provided further grist to the June 4th mill. In a book published there on June 1st, Chen Xitong, who was mayor of Beijing in 1989 and a forceful advocate of the official line, changed his story. In an account that is self-serving and still impossible to verify,Mr Chen says others ran the show. His previous defence of the crackdown, he claims, was scripted for him, and it is “only a matter of time” before Beijing declassifies files showing who was responsible. “Unfair and unjust things will be readdressed one day,” he predicts. That will be too late for Li Wangyang, a labour activist jailed for two decades after Tiananmen, who reportedly hanged himself on June 6th. His relatives call his death suspicious. Too late also for Ya Weilin, aged 73, who hanged himself in Beijing in late May. His son was shot and killed in 1989. Friends said his suicide was “to protest against the government’s brutality”. They called his act “resolute”. from the print edition | China Resolute to the end Jun 15th 2012, 17:05

The “June-4th” Incident was an impediment to China’s economic growth and politics evolution. This incident also had China’s Communist Party (CCP) mask shades of grey. About 1990, China had few formal diplomatic ties in truth with foreign nation - except for United States (medium level) and Japan. Former President Jiang Ze-min was keeping the balance between the principle of Deng’s CCP and foreign nation, with ensuring China’s constant growth in many fields.

For several decades, many researchers or figures about the incident published reflection or criticism while CCP still says very few about this incident because the oppression, for CCP’s 3rd or 4th generation, is an essential means of maintaining “the Republic” (from Jiang) in case of possibly tumult. Most of them intend to focus on two points - one is whether this incident might have been avoided and another is how China and Chinese may be affected in the future direction of political system or the potential anti-Beijing activists.

In recent years, some mask has gradually been unveiled by many released writings such as James Lilley’s (Lee Jie-min) Chapter 19-20 of “China Hands”, Bao Pu’s Part 1 of “Prisoner of the States” and Ezra F. Vogel’s Chapter 20-21 of “Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China”, besides Chen Xi-tong’s release.

From the angle of power, Deng was the utmost head of CCP’s core from 1976 to his death while Zhao, on the surface, kept a role of party secretary. The party’s principle depends on the only - de facto head - that owns the order of People’s Liberation Army (PLA). On one hand, Zhao kept silence and held optimism towards students, led by Wang Dan, Chai Ling and Wuer Kaixi. On the other, Deng and Li Peng had wanted Zhao’s power to be eclipsed for not short time, especially after 13th Party Congress when Zhao was warned by Deng for learning Western-style democracy. The core finally discarded any peaceful treat to the students and did away with Zhao and them.

After the start of the students’ commemoration of the death of Hu Yao-bang, or the rally gathering, Deng listened to some thoughts of younger CCP’s member and had a discussion about the “stability” with Chen Yun, Li Peng and Qiao Shi. Compared with observative Chen Xi-tong’s sayings, these released document, in common, referred to the visit of Mikhail Gorbachev as a mark separating impossible and possible - or say unavoidable - massacre. In the last week before Zhao was kicked out, people in that square became waning with some slogan and so-called “Democratic Statue”. Then, some of them were executed or serving sentences with Li Peng’s demand of Marx-Lenin examination, leaving a questionable photo of “For every student, I come too late. Please go back home quickly.” with his then secretary Wen Jia-bao.

On June 4th every year, some Chinese held the memorial ritual for the death. This year, Hong Kong people, about 180,000 taking part as the organizer said, held a candlelight vigil to mark the 23rd anniversary of the crackdown in Tienanmen Square. The number of this time’s join broke the historic record owing to Chen Guang-cheng case. At the same day, Taiwan’s organizer held similar kind of Tienanmen commemoration, consisting of 600 people, by showing a film of the incident and inviting silent prayers for the victims. Wuer Kaixi, former Kuomintang’s central member of committee, gave a speech on that day’s importance.

Actually, CCP’s structure still remains solid while there is some voice of the incident’s pity. In an interview with NHK (June 8th), a veteran Zhang Shi-jun told media that PLA could do nothing but listened to party’s willing, pardoning them by visiting here again. This incident affected the arrangement of CCP’s core in future. Deng, who abruptly ordered Jiang and Zhu Rong-ji’s succession, tended to consider Hu Jing-tao in 1992, who did good for Deng in 1989’s Lhasa case and “correct way” of learning western politics, as the 4th-generation top. In other words, the next later than Jiang must have the ability to do both oppressive and attention with care.

With the passing time, this past memories already blurs. Wang Dan, the only I contact in the incident, told me thoughts on 2009’s that day while I was listening to his interview by Financial Times. Wang pointed at Xi Jin-ping and Li Ke-qiang’s possible future, giving me some tips. As the few that know the truth of power in my opinion, Wang has moderate attitude toward China’s contemporary but almost of the others cannot. I disclosed Wang’s thoughts to Wen, who later talked of political reform in CNN, and Li, the next prime minister. Wen just said very few were remembered. As Li Peng’s sayings (before that day), any “demo-” can be said only with the economic growth ensured. Taiwan’s Chen Shui-bian exclaimed Li’s visit to Taiwan in 2005 by “(We can) Enjoy democracy in wonder but no need to wait so long.” Yeah, Li’s clear principle of law with fervent belief can bring China into “New China 2.0”.

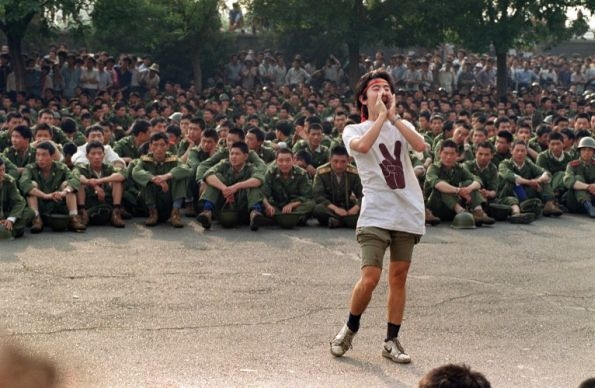

Recommended 6 Report Permalink 筆者在寫下去前,先提供一聯結錄自NHKWorld 英語版:「Asia Insight - Tiananmen No More/洞悉亞洲 - 天安門不再 [HD]」https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XmT7JSEopA8 這張照片是正在發號施令或是帶團康的都算是,就是現在年輕一輩情感比較生疏一些的王丹,當時他僅20歲,就讀北京大學歷史系中國史專業。有關王丹小時候的情形,他的父親王凌雲先生有作了一本傳記說明,「歲月蒼茫:我與兒子王丹」2010年5月由明報出版社發行。王丹在2012年10月由時報出版社「歷史與現場」系列增添一本「王丹回憶錄:從六四到流亡」以及2013年6月由渠成文化「獄中回憶錄」,均可說是完整的自述生平,由此可一窺中國民主化的因果演進及和北京共黨政府的對抗和維權想法等問題。在其後王丹為聯經出版的「中華人民共和國史十五講」(2016年6月17日二版)以西方邏輯來說也很具權威分析觀點。王丹就台灣和香港年輕人來說有點陌生,不過網路上其臉書王丹網站(https://www.facebook.com/%E7%8E%8B%E4%B8%B9%E7%BD%91%E7%AB%99-Wang-Dans-Page-105759983026/)很有聲有色,並且在自由時報副刊和蘋果時報社論有王丹專欄,最近二月才看到一篇「家有小狗」很有感觸。提這些對現在台灣人有點淡忘,好像是真的,若說到東森電視新近人氣的兼職主播李樺仙和她哥裡面的攝影大哥李軍的母親是王丹的親戚,而樺仙的姨婆就是筆者在2014年9月外語導遊受訓時的「台灣地方小吃特色及中國菜系簡介」的李梅仙老師。看看上面那張照片中的王丹怎麼互動來理(或不理)軍隊和北京市民,不知道是否有人會說這逢甲大學國際貿易學系雙主修政治系,現在就讀政治大學EMBA專班的校花的確正的很有道理呢?

至於八九學運的六月三日深夜,現場的北京共和衛隊的連長王建平就是東森電視有名的氣象主播王淑麗的叔公的兒子,這是信中所指出的,帶著32人持衝鋒槍開始進行「平亂」,後來升至副參謀長及武警司令。照片的王佳婉主播是當天臨時上任的江澤民的夫人王冶坪家裡的千金媽媽。 原雜誌作者認為這場事件屬於不公不義之事,的確在這之前中國政府並沒有因文化大革命而被要求檢討及譴責。除了這篇之外,之後筆者曾有數篇繼續寫對六四天安門(或稱八九學運)的看法。除了王丹的傳記和省思外,就是李潔明在「China Hands(中國之手)」第19、20章的所提為老布希總統的駐北京大使的描寫。Ezra F. Vogel 傅高義的「Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China(鄧小平及轉變中的中國)」第20-21章的其1988-89年的生平事略。這本的參考價值在於傅氏訪問江澤民先生過,江曾評論對鄧小平生平的看法。 鮑彤的自1989年4月15日胡耀邦過世寫起的「Prisoner of the States (國家的囚徒:趙紫陽口述密錄)」第一部份,筆者在此及之後曾判定當5月16日趙紫陽會見蘇聯總統戈巴契夫前,似乎鄧小平就已有定見,包括囚禁當時人大常委長萬里,使中國中共的憲法有十天是完全空白的。中央在態度上的顯見及其後的「收拾」,則見於時任總理李鵬(2010年6月由美國西點出版社出版「李鵬六四日記」內也有說明)和在5月10日時任上海市委書記的江澤民在4月30日見面後(趙剛結束訪問北朝鮮行程),第二度因學生集會問題找了趙提案想緩和局勢。在這本書中見到,其實李鵬和時任國家主席楊尚昆(在第一章趙回憶起這兩位,這兩位多少透露一些鄧的態度)本來履次說明領導的位置及名份次序不會變,p23有李鵬要求加緊以柔和態度結束「事情」,甚有p26之中「admirable」和「approval」等字樣「讚賞」學生愛國行為及反貪汙呼聲,所以黨中央在當年組織上不一定反對學生運動,六四事件是時任中共軍委主席鄧小平一意孤行的結果,而李鵬內心兩邊拔河,不太為難又說要重經濟全局而不反對鄧「平亂」,筆者甚至冒險猜鄧於那日有所定見後,自行作共和衛隊突襲以「維穩」的決定。p33-34趙提三大疑點:「屬於反黨、反社會主義之有計畫陰謀」、「改正缺點等於推翻黨及國(的領導)」、「學生罷課聚會是反革命混亂禍源」,這是指說有黑手在推嗎?有哪位如此能耐和有誰說通貨膨脹導致?還有這群集會不是很守秩序嗎? 今年的中共決議可無限期延長國家主席的任期,及更嚴密以黨的思想驅動經濟的決議。上月外媒傳出胡耀邦的遺族有受更嚴密的監視,這和三四年前習近平曾經和這群人合影的態度差了很大。六四至今(2018年)已經過了29年,2009年時筆者記得王丹接受英國金融時報Jamil Anderlini的電話專訪(附錄該記者訪問鮑彤的回憶,如5月28日被送往政治犯集中的秦城監獄),在八九學運時曾任趙紫陽的祕書的溫家寶那天正在第二任的總理位置上,而和胡耀邦同一陣線的前國家副主席習仲勛先生之子正在中國最高領導,而且快要超越毛澤東的權勢。那張黑白相片有溫家寶的相片真是感慨,「我們來得太晚了」。溫家寶在台灣有個親戚,就是東森新聞的鴕鳥主播組長溫淑梅,實在值得玩味。

筆者有在經濟學者之後近六年的討論區有數次提到這場事件的後續,NHKWorld當年報導吾爾開希是不只第一年,以中國國民黨前任中常委的身份在二二八和平公園舉行追思會,後來又曾經數次闖香港進中國本地的海關履次被驅逐(所以筆者不知道為什麼李凈瑜和李明哲基於有不良紀錄又為什麼很順利進得了關),和履次有學者從方勵之夫婦到劉曉波、胡平和胡佳的被聲援也或多或少獲海內外人士的關注,但仍沒有起決定性的影響,他們在內地的組織能力有限,及習近平上任後的強烈維穩措施及新一波紅色教育政策的推行讓他們這群當年八九學運(或所謂零八憲章等延伸)的聲音很難是輿論的主流。現今的中國大陸民眾既希望經濟安定繁榮,也在多元化社會發展同時要政府知道市場和民眾社群的需求。因此如果真有反政府執政當局能力者,這種領導比較是產生於罷工抗議中匯集的人群,根據日經新聞的雜誌版Nikkei Asian Review的報導,四月時各省市黨部領導共同提交給中共中央的報告即提出這些人群的日益劇烈,讓他們也很難服從黨中央的領導。 中國民主化一直是口號甚至仍然就大部份民眾來說是謠言風一陣。大部份的民眾並不是特別會聚集起來想擁立從魏京生到王丹、柴玲、吾爾開希、曹長青、袁紅冰或甚至李洪志、伊力哈木·土赫提、達賴喇嘛成為國家領導,或是胡佳、浦志強或偏好到最近日益使情勢惡化的的在四川或湖南省的工運的領導及基層幹部等人,更不是台北當局或還在台灣覺得自己是中國一部份的車輪牌。李方平是最近反對陣營中還在進行業務而人身自由及中國法定公民權尚算完整的最有名例子,及筆者視為目前法律容許的民間有聲望領導,曾在去年八月底習近平召開的的維權律師座談會曾經以首席露面。 在中國的都市化歷程中,民眾會以自身需求和對群類認同感的培養,大部份是自覺的、以自己所經歷的社會化語言來提及,與之有一些矛盾的中共動員力量仍然很強,但還沒匯集成為有力的違背黨繼續執政的反撲,充其量是對政治、政策和行政措施冷漠。基本上所謂知識份子的串連,至今沒有一次會有成功影響中共當局的執政能力。中國的中產階級正在擴張,但沒有伸張,大部份是庸庸祿祿的一群,而比如有號稱兩百多萬的網路稽查員、公安的大媽和黨的特工和臨時雇員仍然以嚴密的網路控制中國的龐大社群及商務網站。如果有發生阿拉伯之春的類似場面,領導局面的叛軍應該是從原來的社會階層稍具優勢,約中高級白領幹部及基層官員所集結才會起決定性影響,而非所謂知釋份子。因此觀察這兩群的忠誠度與動態便很重要。習近平的人事升遷在兩、三年前均大部份任用「之江新軍」,大多為他在浙江時認識的幹部、鄰近福建的數代習家人之舊識,以及家鄉陝北的原鄉部隊所通稱。數年後一旦省及國務院的部委大多由這些人扶起,被動的派系不滿情緒上升,之江新軍的升遷有的是補原職務前任貪汙所遺留的位置,如果原來的慣例如從共青團考核的機制被忽視甚至取消,政治資源的壟斷令人惴慄不安,這時動亂才會有稍持久、大規模而且稍有「組織」的形成。其他的相關回應筆者在貼出相關文章後會繼續討論。也可透過筆者在首頁提的網頁點選尋找在這之後數年的文章,也有數篇遺留已封閉的討論區過。(https://www.economist.com/user/2791934/comments) 這年引起中國國內外注目的亮點是北京曾經有一名當時參與共和衛隊的張姓幹部,寫信致國務院要求要作平反八九學運和自己後悔的意見書一封,並且乘昇平之時能夠促進社會和諧一次。筆者最後一段寫到陳前總統當著在2005年九月時李克強來台灣的民進黨造勢場子上提及,「不必等到2008年,就能享受自由民主的美好」,這驚鴻一瞥稍寬慰了擔心當時兩岸緊張的人士,在包機直航開放了兩岸的天空後,陳前總統雖不情願但開放包容的想法,隔年宣佈終止國統綱領讓中華民國法律上偏統一的狀態暫停,這之間不少妥協和爭取民眾利益也是民主化的一種表現。 *附2009年八九學運20週年紀念,英國金融時報專題報導訪問鮑彤一文(https://www.ft.com/content/19be8a24-4bdf-11de-b827-00144feabdc0) Jamil Anderlini May 29, 2009

When China’s ubiquitous state security agents want to intimidate a dissident or political activist for the first time, they usually come knocking in the middle of the night with an invitation for “a cup of tea”. Once the tea is served in some secret location, the agents explain that if their guest continues publicly to criticise Communist party rule, the likely consequences range from unemployment to long prison sentences or even “disappearance” for them, their family and friends.

So it seems somehow fitting that Bao Tong, the most senior Communist party official to be jailed as a consequence of the 1989 Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests, should have invited me to tea at his apartment in the west of Beijing.

It was 20 years ago next week, on June 3 and 4 1989, that the People’s Liberation Army opened fire on unarmed demonstrators, killing hundreds, perhaps thousands, of peaceful student protesters and bystanders. As the anniversary of the bloody crackdown approaches, Bao, now 77, remains under house arrest, his apartment watched around the clock and his movements tightly restricted by state security officers. I’d originally invited him for lunch at a restaurant but, as he patiently explained, under the terms of his house arrest it would be more convenient to meet in his home.

He greets me at the door with a wry smile, jet-black hair and a lithe frame wrapped in a Princeton University sweatshirt. It is hard to believe that he spent six years of his life doing hard labour during the Cultural Revolution and then, from 1989, another seven years in solitary confinement in the notorious Qincheng political prison. When I mention the sinister-looking men at the entrance to his apartment block who asked me to explain why I’ve come to see him, his face cracks into a sly grin.

“I’m contributing to the country by stimulating domestic demand, increasing employment and helping solve the financial crisis,” he says. He speaks Mandarin with the soft consonants of a southerner and the confidence characteristic of a senior party cadre. “You only saw three people down there but if I want to go out I’m followed by three groups – one on foot, one in cars and one on motorbikes. Just think – it takes more than 30 people to keep an eye on me so if the government decided to monitor all 1.3bn people in China we could solve the unemployment problem for the whole world!”

While this kind of gallows humour and the satirical use of communist propaganda slogans is common on the anonymous internet, I have never heard a senior Chinese official, even a retired one, talk like this in public.

Bao Tong was born in 1932 in Shanghai, where his father was a clerk in an enamel factory. The young Bao was influenced by two uncles, prominent left-wing intellectuals: one became a professor at Oxford University; the other became famous for a hunger strike aimed at convincing the government of the day to fight the Japanese.

At high school in Shanghai, Bao met his future wife, Jiang Zongcao, an active member of the communist underground who was kicked out of a string of schools for organising demonstrations. She convinced him to join the Communist party in 1949, the year it came to power following a bloody civil war. Comrade Bao quickly worked his way up through the communist bureaucracy, but then in 1969, during the Cultural Revolution, he was denounced and sent to do hard labour at a re-education farm in Manchuria.

After the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, many previously persecuted officials were politically rehabilitated and Bao was assigned to senior government positions. During the 1980s, he worked as a top aide to premier Zhao Ziyang, a liberal reformer who helped usher in a period of political and economic openness in the 1980s, and in 1987 was appointed to the Communist party’s central committee. He served as the minister in charge of political reform and as political secretary to the standing committee of the Politburo, the five-man group that ran the country at that time.

One of the first things I notice in his spartan, dimly lit apartment is a large photograph on his bookshelf of Zhao. Only two weeks ago, Zhao’s secret memoir, Prisoner of the State, was published in Hong Kong – a rare first-hand account of Chinese elite politics. Over the next hour, Bao gives me his own blow-by-blow account of the secret and increasingly intense power struggle that raged during the seven weeks of upheaval that ended with tanks rolling down the Avenue of Eternal Peace in Beijing.

He begins with his verdict: the man who bears full and sole responsibility for ordering the People’s Liberation Army to turn their guns on the people is Deng Xiaoping, the Communist party elder who controlled the leadership from behind the scenes until his death in 1997. Most historians regard Deng as the father of modern China: the architect of its economic reform and opening to the world. But in 1989 his only official title was chairman of the Central Military Commission.

“Most of the students weren’t trying to depose Deng Xiaoping; they were hoping he would carry out reforms,” Bao says. “The problem was Deng felt threatened and he called in the troops. This is how the tragedy happened, a true tragedy in Chinese history.” Zhao, explains Bao, felt the students’ demands for democracy and an end to corruption were exactly what the Communist party itself claimed to stand for, and that a conciliatory approach would be the best way to end the protests.

This difference of approach ultimately proved critical. But Zhao’s struggle to avoid sending in the troops ended on May 17 1989 when, after a state visit to China by then Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, Zhao’s colleagues in the Politburo forced him to resign. In the middle of the night on May 18, Zhao made his final, tearful, public appearance in Tiananmen Square, urging students to give up their struggle and return to class.

In a famous photograph from that night, Wen Jiabao, now premier of China, can be seen standing next to Zhao as he addresses the demonstrators. Bao won’t be drawn on whether Wen was a Zhao sympathiser, as some historians suggest. “Who knows if he supported Zhao? Only he knows.”

His caution reminds me that every word we’re speaking is being recorded and I glance around the room involuntarily, as if I might be able to spot one of the bugs. This line of questioning is not going to do me or my host any good, so I return to 1989 and the days after Zhao’s resignation.

“Many people thought Zhao Ziyang was conspiring to launch a coup against Deng Xiaoping,” Bao says. “In fact, he and I did hatch a ‘conspiracy’ [on the day Zhao was forced to resign], which was to sing the praises of Deng Xiaoping.” Zhao believed he could avert a massacre by appealing for calm, explaining to the masses why Deng was in charge, despite holding no formal government or Communist party positions.

Bao was implicated – and later punished – for his alliance with the discredited Zhao. I ask if he regrets not having tried to plot a real coup with Zhao at that point. “Some people said Zhao Ziyang could copy Yeltsin and climb up on to a tank, but that,” says Bao, “was impossible: no single soldier would listen to Zhao, they didn’t know him at all. They listened to their officers, the officers listened to the generals and the generals listened to Deng Xiaoping.” As Mao Zedong famously said, political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.

Bao describes the night the old men, women and children of Beijing took thermos flasks to the soldiers and begged them not to enter the city; how ordinary citizens built barricades in the streets to protect the students and how the tanks and troops stormed the city. “The tanks were roaring and the bullets were flying into people’s homes. In my building, the son-in-law of a government minister was killed as he was pouring a cup of tea in his living room.”

I look down at the untouched porcelain teacup on the table in front of me. I’ve been so engrossed I haven’t taken one sip and now I’m not sure if it’s my cup or his. Bao’s vivid description belies the fact he was not in Beijing that night and was not able to piece together the whole story until years later, with the help of smuggled western media cuttings.

On May 28 1989, Bao himself was arrested and taken to Qincheng, China’s main political prison since the 1950s. There he became number 8901 – the first prisoner to enter Qincheng in the year 1989 – and was put in a 6m by 6m cement cell with only a stiff wooden board propped on two saw horses for a bed. “I lay down on the board and went to sleep. People ask me why I wasn’t terrified. Before that moment I didn’t know when they would come for me, but now I didn’t need to worry any more.”

There was no door to his cell but a guard sat at a table propped across the entrance; two soldiers stood to attention behind him. The seated guard’s job was to record the prisoner’s every action in a notebook 24 hours a day, one entry a minute, for seven years. Bao chuckles at the frustrating boredom of the job assigned to his captors – “20.00 hours – prisoner 8901 sleeping; 20.01 hours – prisoner 8901 sleeping; 20.02 hours – prisoner 8901 sleeping and so on.”

In 1996 Bao was finally released from prison and placed under house arrest. His jaw tightens slightly as he describes the hardships his family has endured as a result of their relationship. His Princeton-educated son Bao Pu, 42, is a US citizen and the publisher of Zhao’s memoirs in Hong Kong. He is barred from entering China to visit his elderly parents.

But it is Bao Tong’s wife who has suffered the most. He describes the day Zhao Ziyang died in 2005. He and his wife wanted to pay their respects, but were blocked by people guarding the door of the lift in their apartment block, threatening them not to go out. “I explained that it was illegal for them to stop me from going.” The men instead shoved his elderly wife to the ground, breaking her hip. She spent more than two months in hospital. “The Chinese Communist party is just like the Mafia,” says Bao. “If the Mafia boss thinks you might betray him, he will just kill you or throw you into prison for as long as he likes. This is not how a political party or a government should behave.”

For all he and his family have endured, Bao considers himself lucky, compared to those even now imprisoned for supposed crimes related to the 1989 demonstrations, or to those who died in the crackdown or in the brutal witch-hunt that followed.

According to Bao, his tormentors’ niggling fear is that one day this old revolutionary insider might either be rehabilitated and return as a top Communist official or become a figurehead for a new wave of activism. Bao says he still receives a measure of protection from old friends in senior government positions. “I should count myself lucky and express my thanks with the popular slogan: ‘My eternal gratitude to the Communist party and to Chairman Mao!’”

It is in this ironic humour that one senses the real threat to the current leaders in China, even two decades after the Tiananmen massacre and 12 years after the death of Deng Xiaoping. Bao mocks their slogans and denigrates their demigods, but he is, after all, one of them. If he were to be allowed to air his views, they fear the whole authoritarian edifice could start to crumble.

“China has almost erased the memory of Tiananmen by making it illegal to talk about what happened. But there are miniature Tiananmens in China every day, in counties and villages where people try to show their discontent and the government sends 500 policemen to put them down. This is democracy and law with Chinese characteristics.

“The first sentence of the Chinese national anthem goes like this: ‘Arise! All those who refuse to be slaves.’ I believe there will be real democracy in China sooner or later, as long as there are people who want to be treated equally and have their rights respected.

“It will rely on our own efforts, it will depend on when we, the Chinese people, are willing to stand up and protect our own rights.”

The tea is now cold and the table has been set for lunch. Bao’s family is waiting in the other room for me to leave. Even shaking the hand of a foreign journalist could expose them to criticism from the authorities and, after all they’ve been through, I don’t want to be another source of inconvenience. As I leave the lift, I turn my video camera on the security agent sitting at the desk in the lobby. He yells at me to turn it off and I leave the compound in a hurry, 30 pairs of eyes boring a hole in my back.

A few days after this interview, Bao Tong was invited on a tour of a scenic reserve in southern China by the Public Security Ministry. According to his son, he left of his own volition in the company of his security agent entourage last Monday and will not return until June 7, when the sensitive anniversary has passed.

Jamil Anderlini is the FT’s Beijing correspondent

Bao Tong’s apartment West Beijing, China

Tea No charge

Key players in the bloody confrontation of 1989

Li Peng was the hardline premier of China in 1989 and Zhao Ziyang’s main opponent. Often referred to in the aftermath of the crackdown as the “Butcher of Beijing”, he was seen as instrumental in convincing Deng Xiaoping that the student demonstrators posed a threat to the Communist leadership and to Deng himself, writes Jamil Anderlini. Li retained his position as one of the most powerful leaders in China until retirement in 2002. He lives in western Beijing, not far from Bao Tong’s home.

Chen Xitong was mayor of Beijing in 1989 and also supported the military crackdown. In 1995 he was removed from office and sentenced to 16 years in Qincheng prison on charges of corruption – a result of what many political observers believe was a power grab by rivals. He was granted medical parole in 2006.

Liu Xiaobo was one of the most prominent intellectuals to support the student movement in 1989. He helped negotiate with the People’s Liberation Army to allow the last group of students left in Tiananmen Square to leave alive. He has spent the past 20 years in and out of jail for his human rights work and for criticising the Communist party. Last year he was detained for his part in organising “Charter 08”, a blueprint for introducing democracy and rule of law to China.

Wang Dan was a 20-year-old student at Peking University in 1989 and one of the most visible pro-democracy student leaders. He went into hiding after the crackdown but was caught and spent most of the next eight years in prison. In 1998 he was freed on medical parole and exiled to the US, where he gained his PhD in East Asian history last year from Harvard. He is barred from entering China.

In 1989, Wuer Kaixi, then 21, was a student at Beijing Normal University. He earned fame as the hunger striker who rebuked Li Peng on national television. After the crackdown, he was second on the government’s most wanted list but he escaped via Hong Kong to Paris with the help of Operation Yellow Bird, an exercise run jointly by the CIA, Hong Kong democracy groups and Chinese triad gangs. He later studied at Harvard and is a radio presenter in Taiwan.

Chai Ling was a 23-year-old graduate of Peking University. As a student protest leader, she controversially argued that bloodshed was necessary in order to unite China behind the democracy movement, and organised “dare to die” suicide squads. She later escaped to Paris with the help of Operation Yellow Bird. On reaching the US, she attended Princeton and received an MBA from Harvard before setting up her own internet software company. She remains a controversial figure in the Chinese dissident community. 趙紫陽六四前曾說一句話 江澤民稱如雷轟耳 紐約時間: 2016-06-03 12:26 PM

【新唐人2016年06月03日訊】(新唐人記者唐迪綜合報導)「六四事件」是中共二十多年來揮之不去的政治夢魘。2010年6月,六四事件決策者之一李鵬的《六四日記》幾經周折,於中國大陸境外面世。這些日記比較翔實地記錄了這段風雲變幻的中國曆史中,發生的一些鮮為人知的政治事件。其中六四前時任中共總書記的趙紫陽對江澤民整頓上海《導報》,把事態擴大的做法非常不滿,當時對趙紫陽說的一句話,江澤民稱如雷轟耳。 廣告

“六四”28周年的 悼念 —— 悼念“天安門母親”成員徐玨 作者:嚴家祺

今年四月二十四日,“天安門母親”成員徐玨因病去世。二十八年前的六月三日,徐玨的兒子吳向東在一九八九年在北京木樨地被軍警擊中頸部身亡。徐玨生前是中國地質科學院研究員,曾發表過有關六四事件內幕的文章,二十八年來,徐玨沒有一天不是活在傷痛中。

“天安門母親”發言人尤維潔說,自去年有一百三十一名死難者家屬要求平反六四事件以來,已有五人過世,他(她)們是孫恆堯、田淑玲、石峰、王桂榮和徐玨。二十八年來,已有四十六名“六四” 死難者家屬離世。

每到“六四”,我們許多人就會想起丁子霖和天安門母親,想起成千上萬“六四”受難者,想起一個個當年遭難的同事和朋友,他們的後半生無一不在痛苦中煎熬。

與“六四”受難者境況成為對比的是“六四”受益者。“六四”的第二十八年還沒有走過一半,兩位“六四”受益者受到了中國和世界華人社會的關注。一是“六四”當年擔任北京大學學生會主席的肖建華,二是“六四”時三十六歲、後任武警司令、中央軍委聯合參謀部副參謀長的王建平上將,今年四月二十三日在北京沙河總政看守所用一根筷子戳進頸動脈自殺,這是罪有應得。

一九八九年,當年肖建華的立場與他的同學王丹相反,他先後投靠陳希同、江澤民,促成了他二十八年來從一個“無產者”轉變為擁有上千億元資產的金融巨鱷。據報導,二十八年前的六月三日二十三時,王建平所在的部隊從京郊駐地沙河機場出發,沿東直門橋、東壩河、酒仙橋、三元橋、農展館竄進,沿途人山人海,軍車寸步難行,王建平組織了“防暴突擊隊”,發射紅色信號彈和煙幕罐,集中三十二支衝鋒槍集體封空點射,一時槍聲震天,子彈火花四射,人群被驅散,該軍這才於六月四日淩晨趕到天安門廣場。事後王建平立三等功,先後升任副旅長、旅長、師長、武警部隊副參謀長,在周永康任武警部隊第一政委期間,王建平又升任武警部隊司令、中共十七屆中央候補委員、委員、十八屆中央委員。

“六四”受難者也包括許多香港人,香港黃雀行動的參與者羅海星,成功救助多名民運人士逃亡,在營救王軍濤時失手被捕,被判五年監禁,他和他夫人周密密也是“天安門事件”的受難者。黃雀行動歷時九個月,救助一百三十三人逃亡,失去弟兄四名,兩人是快艇完成救人任務返航時大霧中撞上水泥船,當場死亡,兩人是快艇救人遇上中國巡邏船,高速逃亡,失控翻沉,遇溺而亡。這四位都是黃雀行動的實際總指揮陳達鉦的弟兄。

“六四”受難者一年又一年發出呼聲,中國的執政者始終置若罔聞。一個國家如果連光天化日發生的、成千上萬人見證的大屠殺,二十八年不能在大地上恢復真相,這個國家的人心是不可能平的。上世紀中國的改革開放是“天安門事件”翻案、中國恢復了正義的的結果。只要屠殺人民不受追究,不論以“人民的名義”貪污,還是以“人民的名義”反腐,周永康、郭伯雄、王建平和肖建華就會不斷產生,普遍性的貪污腐敗和法制黑暗就不可能消除。

天安門事件有兩次,一次是一九七六年,另一次是一九八九年。這兩次天安門事件事件,都是自發的、和平的抗議運動,反映的是民意,與文化大革命的“奉旨造反”絕然不同。第一次“天安門事件”的翻案,把鄧小平推上了台,第二次天安門事件,卻遭到了鄧小平一意孤行、慘無人道的大屠殺。“六四”不翻案,中國就永遠不會有正義。周永康、郭伯雄、王建平、肖建華和大大小小的貪官污吏正是“六四屠殺”的產物。中國大地上照不到正義的陽光,每到“六四”,相隔大海大洋,總聽到遠方中國傳來的苦難哭泣聲。二十八年來,中國政府沒有做一點撫平“六四”傷痛的事,只是在後來企圖淡化“六四”。“六四”不翻案,傷痛難撫平 。“六四”翻案,也只能減緩無盡的傷痛。

我不相信,這一愈來愈沉重、悲哀、痛苦的聲音,不會撼動中國,不會改變中國!

(寫於“六四”二十八周年前夕,2017-6-1《前哨》月刊) 廣告 |

||

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |