字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/05/02 23:10:29瀏覽72|回應0|推薦0 | |

The slowing economyStimulus or not ?China tries to repeat the successes, without the mistakes, of the 2008 stimulusJun 2nd 2012 | HONG KONG | from the print edition DURING a trip to Hubei province in central China from May 18th to 20th China’s prime minister, Wen Jiabao, argued that the government should give “more priority to maintaining growth”. This was hardly a bombshell. His words nonetheless reassured investors who felt that the government had been late in reacting to the sharp slowdown in China’s economy revealed by a run of bad figures, including a drop in industrial growth to its most sluggish rate since mid-2009. A few days later the government began to back his words with deeds, speeding the approval of infrastructure projects, permitting three huge investments in steel plants, and increasing its financing for public housing. This came on top of 36 billion yuan ($5.7 billion) of subsidies for energy-saving household appliances and ongoing efforts to increase bank lending. The Ministry of Railways, for example, said it had secured a generous line of credit. This was a “mini-me” stimulus, according to Stephen Green of Standard Chartered, a diminutive clone of the November 2008 package unveiled in response to the global financial crisis. But this mini-stimulus still lacked something that distinguished the earlier package: a price tag. The 2008 stimulus was billed from the start as a 4 trillion yuan package ($586 billion at 2008 exchange rates), an enormous sum that amounted to about 13% of China’s GDP (although the stimulus was scheduled to last more than two years). No comparable total has yet been offered for China’s piecemeal efforts this month. In this section This omission is not just a statistical oversight. It provides a clue to the government’s deep ambivalence as it considers how to respond to worries at home and abroad. The 4 trillion yuan sum in 2008 showed that the government was prepared to go to almost any lengths to revive growth. That commitment helped to lift the spirits of entrepreneurs, officials and consumers, encouraging them to keep spending too. The message sent was as important as the amount spent. In retrospect, that message was heard too loudly and clearly. Local governments and banks rushed to take advantage of the central authorities’ indulgence while it lasted. The surge in spending and lending succeeded in rescuing China’s economy from the crisis. But it left an awkward legacy of stubborn inflation, messy local-government finances and skewed investment. The central government does not want to repeat that mistake. It has therefore refrained from advertising the scope of its commitment to growth. But investors abhor a vacuum. In the absence of any official estimate of the size of the stimulus, market-watchers looked for an unofficial figure to fill the gap. In a research note on May 28th Dong Tao of Credit Suisse, a bank, calculated that the extra investment orchestrated by the government might amount to 2 trillion yuan, although he cautioned that it was “too early to come up with a precise quantification”. His estimate nonetheless suggested that the “mini-me” stimulus of 2012 might not be so mini after all. The figure was seized on by the media, stirring a modest rally in Asian shares. If the government was concerned only with growth, it might have been happy with this immediate revival of animal spirits. Instead it chose to quash it. A report from Xinhua, the official Chinese news agency, pointed out on May 29th that “there won’t be any massive stimulus plan to achieve high growth”. That was enough to undo the stockmarket rally. The central government thus seems keen to dispel any suggestion that its 2012 stimulus efforts might entail the same loss of discipline as in 2008. The mini-me stimulus will be both smaller and better behaved. from the print edition | China Stimulus or not ?Jun 7th 2012, 16:49

The worry about slowing economies of BRICs is increasing. The present prediction of Brazil’s economy is 3.3%, Russia’s is 3.5%, India’s is 7.1%, China’s is 8.3% and South Africa is 2.8%. India is nearly to be said that there will be no high economic growth (above 7%) afterwards. And China, succeeding in 2008’s “Holding Eight”, is facing the decline of numerous kinds of index. China cannot directly surrender to the fate of moon-sun circle; instead, Bejing’s centre may monitor the several items closely and carefully. For both inside and outside China, China’s number of economic growth is needed to keep high enough to push forward or to become a hopeful solution to European debt crisis.

After last week’s special report, the Economist released this article as well as Jin Li-qun’s prediction. Basically, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is the key to China’s recent 30-year prosperity. In addition to Taiwanese capital, the capital’s inflow of foreign investment, especially Japanese and South Korean, donates to Chinese economy for growing GDP along with young Chinese entrepreneurs, who becomes world’s top wealth at a rate of logarithm. Surfing the postwar history of Japan, Taiwan and South Korean economic development, they cultivate their own unique kinds of business for export after a period of hardworking manufacturers. But there is a note that you may pay attention to - China’s affair always has its unique formula to evaluate.

In pessimistic aspect, experiencing industrial structure changes - including the decline of FDIs acceleration, unsteady CPI and the cost of manufacturers - some Chinese region become market rather than industrial parks. Last month, Xinhua reported Beijing “has no plan for large-scale stimulus” as 2008’s measles injection of market manipulation. In other words, Beijing may respect the mechanism of free market instead of market intervention. Seemingly, there are many bloggers saying China should hold high economic growth anyway. But this year is a good start of advanced trial of free market, isn’t it? Many theories or formula around the world cannot suit China’s affair, even leading to an error in such this discussion. One should be careful of talks about China, giving encouragement rather than despicable attitude.

Being taken unstably social harassment and the discrepancy of poor-rich and inner west - eastern coast into consideration, China have been choosing a way of high risk with high benefit and high status of world’s generator. Conspicuously, some financial institution reach the previous expectation of international conglomerate with Beijing’s long-term fiscal expansionary measures, which includes massive adjustment of financial system. Last October, Beijing’s latest reorganization of financial supervision demonstrated the next fiscal reconstruction, a kind of strategic adjustment of the restructuring. As the disclosure of fifth-generation top leaders to me, Beijing wants the vision of China’s farther sustainable development and tries to keep 7% high economic growth even over 2030. These big heads intends to make market freer with efficient management of planned market economy for a longer way to go.

Before the per capita of GDP More promotion of FDI and more measurement of exciting transition from small-medium into world-class business, which both prime minister - the present Wen Jia-bao and next Li Ke-qiang emphasize may continue to process extensively. Today, Beijing cut interest rates for first time since 2008 due to the intention of capital inflow into market. The details contain the drop of one-year lending rate to 6.31 percent from 6.56 percent and the fall of one-year deposit rate to 3.25 percent from 3.5 percent. In the following months before the takeover of CCP’s next generation, a series of reform on financial system is unavoidably due to be carried out while both pessimist and optimist still argue for a while. Don’t do too much reform while adjusting Chinese economy until the money is enough to be a reasonable buyer helping the world do more re-allocation.

Compared with other BRICs or rising economy like ASEAN, China is a place inclined to get more fortune and memory, although you take high risk. China assumes leadership of developed nation about economic growth; furthermore, China already play a globally major role, difficult to be outsider of this world anymore. The last week’s issue referred to a bike in 19th century’s China to rationalize the contemporary China’s economy. Through the rapid development of China for more than one generation, Katie Melua’s “9 million bicycle in Beijing” and Yoko Kanno’s “the reform on openness of Chinese 1.2 bn” reflect foreigner common thoughts. Very soon, these bicycle turn to luxurious automobile and super high railway. The outsiders still be welcomed if showing the willingness of making friends with China but some prejudice may affect the whole vision or say “Heavy Rotation”, by Japan’s AKB48, and moreover Chinese destiny.

Recommended 5 Report Permalink 這篇是隨著時序如夏,2012年時中國的經濟也轉熱。溫家寶總理一連串彈性的經濟寬鬆措施,使得中國經濟在短期內尚能維持高成長,但在長期較缺乏政策和國際觀的佈局,而國營事業的投資受到了舉債的限度,同時又無法對內部進行改革,鋪張浪費或當時有人傳言薄熙來為主的系統貪汙疑雲。是直到了習近平提出一帶一路政策,又果然周永康和令計劃的一連串醜聞風暴於一年多後,作為整頓中共黨政的殷鑑。相較於同時期其他新興經濟體BRICS的四國及東南亞、非洲各國,中國還是值得歐美日外資投資的。 這篇討論起是否刺激經濟有其限度,大部份是問說可否再稍大幅度,又稍回憶起2008年萊曼兄弟重創中國經濟的問題,經濟學者雜誌編輯擔心中國經濟結構無法承受再下一波的不景氣。又要趕緊攢錢又要不能過劇改變而壞了結構,或說是中國政府不好控制而不利計畫型的國家資本主義的運作。 筆者寫作上述此篇回文提意見時曾經存檔資料文章,看過下文、Daily Chart對中國經濟的掌握及預期,與附在本篇最末即回文中所提的Special Report前一周的數篇雜誌專題報導第1、3、4、5、9部份內容並附上圖表。這兩年的經濟學者雜誌很喜歡回顧中國三十多年改革開放的經濟起步剪影。筆者就呼應了這個風潮,拿再十年前的縮影,2000年之際的Katie Melua 的 9 million bicycle in Beijing共襄盛舉。 Resilient ChinaHow strong is China’s economy?Despite a recent slowdown, the world’s second-biggest economy is more resilient than its critics thinkMay 26th 2012 | from the print edition

CHINA’S weight in the global economy means that it commands the world’s attention. When its industrial production, house building and electricity output slow sharply, as they did in the year to April, the news weighs on global stockmarkets and commodity prices. When its central bank eases monetary policy, as it did this month, it creates almost as big a stir as a decision by America’s Federal Reserve. And when China’s prime minister, Wen Jiabao, stresses the need to maintain growth, as he did last weekend, his words carry more weight with the markets than similar homages to growth from Europe’s leaders. No previous industrial revolution has been so widely watched. But rapid development can look messy close up, as our special report this week explains; and there is much that is going wrong with China’s economy. It is surprisingly inefficient, and it is not as fair as it should be. But outsiders’ principal concern—that its growth will collapse if it suffers a serious blow, such as the collapse of the euro—is not justified. For the moment, it is likely to prove more resilient than its detractors fear. Its difficulties, and they are considerable, will emerge later on. In this section · »How strong is China’s economy? Unfair, but not unstable Outsiders tend to regard China as a paragon of export-led efficiency. But that is not the whole story. Investment spending on machinery, buildings and infrastructure accounted for over half of China’s growth last year; net exports contributed none of it. Too much of this investment is undertaken by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which benefit from implicit subsidies, sheltered markets and politically encouraged loans. Examples of waste abound, from a ghost city on China’s northern steppe to decadent resorts on its southern shores. China’s economic model is also unfair on its people. Regulated interest rates enable banks to rip off savers, by underpaying them for their deposits. Barriers to competition allow the SOEs to overcharge consumers for their products. China’s household-registration system denies equal access to public services for rural migrants, who work in the cities but are registered in the villages. Arbitrary land laws allow local governments to cheat farmers, by underpaying them for the agricultural plots they buy off them for development. And many of the proceeds end up in the pockets of officials. This cronyism and profligacy leads critics to liken China to other fast-growing economies that subsequently suffered a spectacular downfall. One recent comparison is with the Asian tigers before their financial comeuppance in 1997-98. The tigers’ high investment rates powered growth for a while, but they also fostered a financial fragility that was cruelly exposed when exports slowed, investment faltered and foreign capital fled. Critics point out that not only is China investing at a faster rate than the tigers ever did, but its banks and other lenders have also been on an astonishing lending binge, with credit jumping from 122% of GDP in 2008 to 171% in 2010, as the government engineered a bout of “stimulus lending”. Yet the very unfairness of China’s system gives it an unusual resilience. Unlike the tigers, China relies very little on foreign borrowing. Its growth is financed from resources extracted from its own population, not from fickle foreigners free to flee, as happened in South-East Asia (and is happening again in parts of the euro zone). China’s saving rate, at 51% of GDP, is even higher than its investment rate. And the repressive state-dominated financial system those savings are kept in is actually well placed to deal with repayment delays and defaults. Most obviously, China’s banks are highly liquid. Their deposit-taking more than matches their loan-making, and they keep a fifth of their deposits in reserve at the central bank. That gives the banks some scope to roll over troublesome loans that may be repaid at a later date, or written off at a more convenient time. But there is also the backstop of the central government, which has formal debts amounting to only about 25% of GDP. Local-government debts might double that proportion, but China plainly has enough fiscal space to recapitalise any bank threatened with insolvency. That space also gives the government room to stimulate growth again, should exports to Europe fall off a cliff. China’s government spent a lot on infrastructure when the credit crunch struck its customers in the West. But there is no shortage of other things it could finance. It could redouble its efforts to expand rural health care, for example. China still has only one family doctor for every 22,000 people. If ordinary Chinese knew that their health would be looked after in their old age, they would save less and spend more. Household consumption accounts for little more than a third of the economy. Time is on my side That underlines the longer-term problem China faces. The same quirks and unfairnesses that would help it withstand a shock in the next few years will, over time, work against the country. China’s phenomenal saving rate will start falling, as the population ages and workers become more expensive. Capital is also already becoming less captive. Fed up with the miserable returns on their deposits, savers are demanding alternatives. Some are also finding ways to take their money out of the country, contributing to unusual downward pressure on the currency. China’s bank deposits grew at their slowest rate on record in the year to April. So China will have to learn how to use its capital more wisely. That will require it to lift barriers to private investment in lucrative markets still dominated by wasteful SOEs. It will also require a less cosseted banking system and a better social-security net, never mind the political and social reforms that will be needed in the coming decade. China’s reformers have a big job ahead, but they also have some time. Pessimists compare it to Japan, which like China was a creditor nation when its bubble burst in 1991. But Japan did not blow up until its income per head was 120% of America’s (at market exchange rates). If China’s income per head were to reach that level, its economy would be five times as big as America’s. That is a long way off. from the print edition | Leaders

Pedalling prosperityChina’s economy is not as precarious as it looks, says Simon Cox. But it still needs to changeMay 26th 2012 | from the print edition

IN 1886 THOMAS STEVENS, a British adventurer (pictured), set off on an unusual bicycle trip. He pedalled from the flower boats of Guangzhou in China’s south to the pagodas of Jiujiang about 1,000km (620 miles) to the north. He was disarmed by the scenery (the countryside outside Guangzhou was a “marvellous field-garden”) and disgusted by the squalor (the inhabitants of one town were “scrofulous, sore-eyed, and mangy”). His passage aroused equally strong reactions from the locals: fascination, fear and occasional fury. In one spot a “soul-harrowing” mob pelted him with stones, bruising his body and breaking a couple of his bicycle’s spokes. A century later the bike was no longer alien to China; it had become symbolic of it. The “bicycle kingdom” had more two-wheelers than any other country on Earth. Many of those bikes have since been replaced by cars—one obvious sign of China’s rapid development. But even today the bicycle looms large in the battle for China’s soul. In this special report

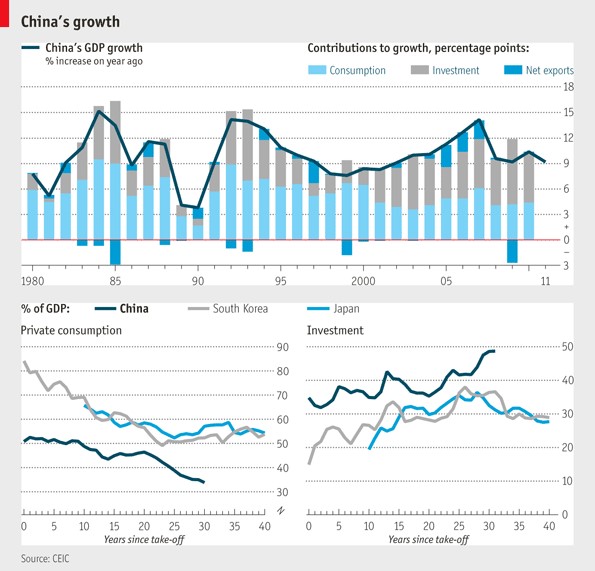

Sources & acknowledgementsReprints Related topics For China’s fast-diminishing population of poor people, bikes remain an important beast of burden, piled high with recycled junk. For China’s fast-expanding population of city slickers, the bicycle represents everything they want to leave behind. “I’d rather cry in the back of your BMW than laugh on the back of your bicycle,” as China’s material girls say. Some dreamers in government see a return to the bike as an answer to China’s growing problems of prosperity—pollution, traffic and flab. The country’s National Development and Reform Commission wants government officials to cycle to work one day a week, though only if the distance is less than 3km. Even if it is a fading symbol of Chinese society, the bicycle remains a tempting metaphor for its economy. Bikes—especially when heavily laden—are stable only as long as they keep moving. The same is sometimes said about China’s economy. If it loses momentum, it will crash. And since growth is the only source of legitimacy for the ruling party, the economy would not be the only thing to wobble. From 1990 to 2008 China’s workforce swelled by about 145m people, many of them making the long journey from its rural backwaters to its coastal workshops. Over the same period the productivity of the workforce increased by over 9% a year, according to the Asian Productivity Organisation (APO). Output that used to take 100 people in 1990 required fewer than 20 in 2008. All this meant that growth of 8-10% a year was not a luxury but a necessity. But the pressure is easing. Last year the ranks of working-age Chinese fell as a percentage of the population. Soon their number will begin to shrink. The minority who remain in China’s villages are older and less mobile. Because of this loss of demographic momentum, China no longer needs to grow quite so quickly to keep up. Even the government no longer sees 8% annual growth as an imperative. In March it set a target of 7.5% for this year, consistent with an average of 7% over the course of the five-year plan that ends in 2015. China has been in the habit of surpassing these “targets”, which represent a floor not a ceiling to its aspirations. Nonetheless the lower figure was a sign that the central leadership now sees heedless double-digit growth as a threat to stability, not a guarantee of it. The penny-farthing theory Stevens’s 1886 journey across south-east China was remarkable not only for the route he took but also for the bike he rode: a “high-wheeler” or “penny-farthing”, with an oversized wheel at the front and a diminutive one at the rear. The contraption is not widely known in China. That is a pity, because it provides the most apt metaphor for China’s high-wheeling economy. The large circumference of the penny-farthing’s front wheel carried it farther and faster than anything that preceded it, much as China’s economy has grown faster for longer than its predecessors. Asked to name the big wheel that keeps China’s economy moving, many foreign commentators would say exports. Outside China, people see only the Chinese goods that appear on their shelves and the factory jobs that disappear from their shores; they do not see the cities China builds or the shopping aisles it fills at home. But the contribution of foreign demand to China’s growth has always been exaggerated, and it is now shrinking. It is investment, not exports, that leads China’s economy. Spending on plant, machinery, buildings and infrastructure accounted for about 48% of China’s GDP in 2011. Household consumption, supposedly the sole end and purpose of economic activity, accounts for only about a third of GDP (see chart 1). It is like the small farthing wheel bringing up the rear.

A disproportionate share of China’s investment is made by state-owned enterprises and, in recent years, by infrastructure ventures under the control of provincial or municipal authorities but not on their balance sheets. This investment has often been clumsy. In the 1880s, according to Stevens, China showed a “scrupulous respect for individual rights and the economy of the soil”. The road he pedalled took many wearisome twists and turns to avoid impinging on any private property or fertile plot. These days China’s roads run straight. Between 2006 and 2010 local authorities opened up 22,000 sq km of rural land, an area the size of New Jersey, to new development. China’s cities have grown faster in area than in population. This rapid urbanisation is a big part of the country’s economic success. But it has come at a heavy price in depleted natural resources, a damaged environment and scrupulously disrespected property rights.

The imbalance between investment and consumption makes China’s economy look precarious. A cartoon from the 1880s unearthed by Amir Moghaddass Esfehani, a Sinologist, shows a Chinese rider losing control of a penny-farthing and falling flat on his face. A vocal minority of commentators believe that China’s economy is heading for a crash. In April industrial output grew at its slowest pace since 2009. Homebuilding was only 4% up on a year earlier. Things are looking wobbly. But China’s economy will not crash. Like the high-wheeled penny-farthing, which rolled serenely over bumps in the road, it is good at absorbing the jolts in the path of any developing country. The state’s influence over the allocation of capital is the source of much waste, but it helps keep investment up when private confidence is down. And although China’s repressed banking system is inefficient, it is also resilient because most of its vast pool of depositors have nowhere else to go. Not so fast The penny-farthing eventually became obsolete, superseded by the more familiar kind of bicycle. The leap was made possible by the invention of the chain-drive, which generated more oomph for every pedal push. China’s high-wheeling growth model will also become obsolete in due course. As the country’s workforce shrinks and capital accumulates, its saving rate will fall and new investment opportunities will become more elusive. China will have to get more oomph out of its inputs, raising the productivity of capital in particular. That will require a more sophisticated financial system, based on a more complex set of links between savers and investors. Other innovations will also be needed. China’s state-owned enterprises emerged stronger—too strong—from the downsizing of the 1990s, but the country’s social safety net never recovered. Thus even as the state invests less in industrial capacity, it will need to spend more on social security, including health care, pensions, housing and poverty relief. That will help boost consumer spending by offering rainy-day protection.

Keep those wheels turning

The chain-drive was not the only invention required to move beyond the penny-farthing. The new smaller wheels also needed pneumatic tyres to give cyclists a smoother ride. In the absence of strong investment to keep employment up and social unrest down, China’s state will also need a new way to protect its citizens from bumps in the road ahead.

from the print edition | Special report InvestmentPrudence without a purposeMisinvestment is a bigger problem than overinvestmentMay 26th 2012 | from the print edition

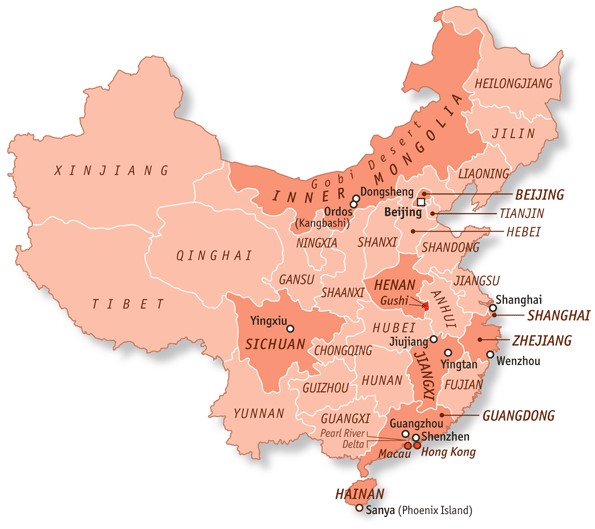

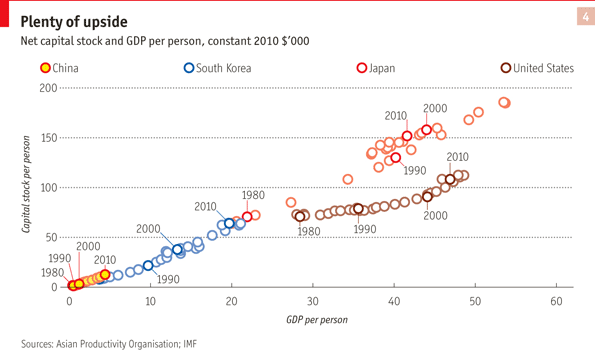

GENGHIS KHAN SQUARE in Kangbashi, a new city in the northern province of Inner Mongolia, is as big as Tiananmen Square in Beijing. But unlike Tiananmen Square, it has only one woman to sweep it. It takes her six hours, she says, though longer after the sandstorms that sweep in from the Gobi desert. Kangbashi, or “new Ordos”, as it is known, is easy to clean because it is all but empty. China’s most famous “ghost city”, it has attracted a lot of journalists eager to illustrate China’s overinvestment, but not many residents. Ordos was one of the prime exhibits in an infamous presentation by Jim Chanos, a well-known short-seller, at the London School of Economics in January 2010. Mr Chanos argued that China’s growth was predicated on an unsustainable mobilisation of capital—investment that provides only for further investment. China, he quipped, was “Dubai times 1,000”. In this special report · The retreat of the monster surplus · »Prudence without a purpose His tongue-in-cheek reference to the bling-swept, debt-drenched emirate caused a stir. But not everywhere in China shrinks from the comparison. One property development that actively courts it is Phoenix Island, off the coast of tropical Sanya, China’s southernmost city. It is a largely man-made islet, much like Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah. Its centrepiece will be a curvaceous seven-star hotel, rather like Dubai’s Burj Al Arab, only shaped like a wishbone not a sail. The five pod-like buildings already up resemble the unopened buds of some strange flower. Coated in light-emitting diodes, they erupt into a lightshow at night, featuring adverts for Chanel and Louis Vuitton. After a visit to Ordos or Sanya, it is tempting to agree with Mr Chanos that China has overinvested from its northern steppe to its southern shores. But what exactly does it mean for a country to “overinvest”? One clear sign would be investment that was running well ahead of saving, requiring heavy foreign borrowing and buying. The result could be a currency crisis, like the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. Some veterans of that episode worry about China’s reckless investment in tasteless property. But although China invests more of its GDP than those crisis-struck economies ever did, it also saves far more. It is a net exporter of capital, as its controversial current-account surplus attests. Indeed, for every critic bashing China for reckless investment spending there is another accusing it of depressing world demand through excessive thrift. China is in the odd position of being cast as both miser and wanton. Even an extravagance like Kangbashi is best understood as an attempt to soak up saving. The Ordos prefecture, to which it belongs, is home to a sixth of China’s coal reserves and a third of its natural gas (not to mention its rare earths and soft goat’s wool). According to Ting Lu of Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Kangbashi is an attempt to prevent Ordos’s commodity earnings from disappearing to other parts of the country. China as a whole saved an extraordinary 51% of its GDP last year. Until China’s investment rate exceeds that share, there is no cause for concern, says Qu Hongbin of HSBC. Anything China fails to invest at home must be invested overseas. “The most wasteful investment China now has is US Treasuries,” he adds. When talking about thrift, economists sometimes draw on a parable of prudence written three centuries ago by Daniel Defoe. In that novel the resourceful Robinson Crusoe, shipwrecked on a remote island, saves and replants four quarts of barley. The reward for his thrift is a harvest of 80 quarts, a return of 1,900%. Castaway capital Investment is made out of saving, which requires consumption to be deferred. The returns to investment must be set against the disadvantage of having to wait. In Robinson Crusoe, thesaving and the investing are both done by the same Englishman, alone on his island. In a more complicated economy, households must save so that entrepreneurs can invest. In most economies their saving is voluntary, but China has found ways of imposing the patience its high investment rate requires. Michael Pettis of Guanghua School of Management at Peking University argues that the Chinese government suppresses consumption in favour of producers, many of them state-owned. It keeps the currency undervalued, which makes imports expensive and exports cheap, thereby discouraging the consumption of foreign goods and encouraging production for foreign customers. It caps interest rates on bank deposits, depriving households of interest income and transferring it to corporate borrowers. And because some of China’s markets remain largely sheltered from competition, a few incumbent firms can extract high prices and reinvest the profits. The government has, in effect, confiscated quarts of barley from the people who might want to eat them, making them available as seedcorn instead. What has China got in return? Investment, unlike consumption, is cumulative; it leaves behind a stock of machinery, buildings and infrastructure. If China’s capital stock were already too big for its needs, further thrift would indeed be pointless. In fact, though, the country’s overall capital stock is still small relative to its population and medium-sized relative to its economy. In 2010, its capital stock per person was only 7% of America’s (converted at market exchange rates), according to Andrew Batson and Janet Zhang of GK Dragonomics, a consultancy in Beijing. Even measured at purchasing-power parity, China has only about a fifth of America’s capital stock per person, depending on how its PPP rate is calculated.

China needs to “produce lots more of almost everything”, argues Scott Sumner of Bentley University, even if it does not produce “everything in the right order”. Its furious homebuilding, for example, has unnerved the government and cast a shadow over its banks, which worry about defaults on property loans. But it still needs more places for people to live. In 2010 it had 140m-150m urban homes, according to Rosealea Yao of GK Dragonomics, 85m short of the number of urban households. About three-quarters of China’s migrant workers are squeezed into rented housing or dormitories provided by their employer. Nor is China’s capital stock conspicuously large relative to the size of its economy. It amounted to about 2.5 times China’s GDP in 2008, according to the APO. That was the same as America’s figure and much lower than Japan’s. Thanks to China’s stimulus-driven investment spree, the ratio increased to 2.9 in 2010, but that still does not look wildly out of line. Malinvestors of great wealth In Defoe’s tale, Robinson Crusoe spends five months making a canoe for himself, felling a cedar-tree, paring away its branches and chiselling out its innards. Only after this “inexpressible labour” does he find that the canoe is too heavy to be pushed the 100 yards to the shore. That is not an example of overinvestment (Crusoe did need a canoe), but “malinvestment”. Crusoe devoted his energy to the wrong enterprise in the wrong place. It is surprisingly hard to show that China has overinvested, but easier to show that it has invested unwisely. Of China’s misguided canoe-builders, two are worth singling out: its local governments (see article) and its state-owned enterprises (SOEs). China’s SOEs endured a dramatic downsizing and restructuring in the 1990s. Thousands of them were allowed to go bankrupt, yet those that survived this cull remain a prominent feature of Chinese capitalism. Even in the retail, wholesale and restaurant businesses there are over 20,000 of them, according to Zhang Wenkui of China’s Development Research Centre. SOEs are responsible for about 35% of the fixed-asset investments made by Chinese firms. They can invest so much because they have become immensely profitable. The 120 or so big enterprises owned by the central government last year earned net profits of 917 billion yuan ($142 billion), according to their supervisor, the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC). It cites their profitability as evidence of their efficiency. But even now, returns on equity among SOEs are substantially lower than among private firms. Nor do SOEs really “earn” their returns. The markets they occupy tend to be uncompetitive, as the OECD has shown, and their inputs of land, energy and credit are artificially cheap. Researchers at Unirule, a Beijing think-tank, have shown that the SOEs’ profits from 2001 to 2008 would have turned into big losses had they paid the market rate for their loans and land. Even if the SOEs deserved their large profits, they would not be able to reinvest them if they paid proper dividends to their shareholders, principally the state. Since a 2007 reform, dividends have increased to 5-15% of profits, depending on the industry. But in other countries state enterprises typically pay out half, according to the World Bank. Moreover, SOE dividends are not handed over to the finance ministry to spend as it sees fit but paid into a special budget reserved for financing state enterprises. SOE dividends, in other words, are divided among SOEs. The wrong sort of investment Loren Brandt and Zhu Xiaodong of the University of Toronto argue that China’s worst imbalance is not between investment and consumption but between SOE investment and private investment. According to their calculations, if state capitalists had not enjoyed privileged access to capital, China could have achieved the same growth between 1978 and 2007 with an investment rate of only 21% of GDP, about half its actual rate. A similar conclusion was reached by David Dollar, now at America’s Treasury, and Shang-Jin Wei of Columbia Business School. They reckon that two-thirds of the capital employed by the SOEs should have been invested by private firms instead. Karl Marx made his case for collective ownership of the means of production in “Das Kapital”. Messrs Dollar and Wei called their riposte “Das (Wasted) Kapital”. Perhaps the best that can be said of China’s SOEs is that they give the country’s ruling party a direct stake in the economy’s prosperity. Li-Wen Lin and Curtis Milhaupt of Columbia University argue that the networks linking the party to the SOEs, and the SOEs to each other, help to forge an “encompassing” coalition, a concept they draw from Mancur Olson, a political scientist. The members of such a coalition “own so much of the society that they have an important incentive to be actively concerned about how productive it is”. China’s rulers not only own large swathes of industry, they have also installed their sons and daughters in senior positions at the big firms. The SOEs provide some reassurance that the government will remain committed to economic growth, according to Mr Milhaupt and another co-author, Ronald Gilson. The party officials embedded in them are like “hostages” to economic fortune, “the children of the monarch placed in the hands of those who need to rely upon the monarch”. That gives private entrepreneurs confidence, because the growth thus guaranteed will eventually benefit them as well—although they will have to work harder for their rewards. What are the implications of China’s malinvestment for its economic progress? At its worst, China’s growth model adds insult to injury. It suppresses consumption and forces saving, then misinvests the proceeds in speculative assets or excess capacity. It is as if Crusoe were forced to scatter more than half hisbarley on the soil, then leave part of the harvest to rot. The rot may not become apparent at once. Goods for which there is no demand at home can be sold abroad. And surplus plant and machinery can be kept busy making capital goods for another round of investment that will only add to the problem. But when the building dust settles, a number of consequences become clear. First, consumption is lower than it could be, because of the extra saving. GDP, properly measured, is also lower than it appears, because so much of it is investment, and some of that investment is ultimately valueless. It follows that the capital stock, properly measured, is also smaller than it seems, because a lot of it is rotten. That would make for a very different kind of island parable, a tale of needless austerity and squandered effort. Fortunately there is another side to China’s story. It has not only accumulated physical capital but also acquired more know-how, better technology and cleverer techniques. That is why foreign multinationals in the country rely on local suppliers—and also why they fear local rivals. A Chinese motorbike-maker studied by John Strauss of the University of Southern California and his co-authors started out producing the metal casings for exhaust pipes. Then it learnt how to make the whole pipe. Next it mastered the pistons. Eventually it made the entire bike. China “bears” like Mr Chanos sometimes neglect this side of the country’s progress. In his 2010 presentation he compared China to the Soviet Union, another empire in the east that enjoyed a stretch of beguiling economic growth. Like the Soviet command economy, China is good at marshalling inputs of capital and labour, he pointed out, but China has failed to generate growth in output per input, just as the Soviet Union failed before it. Yet this analogy with the Soviet Union is preposterous. Economists refer to a rise in output per input of capital and labour as a gain in “total factor productivity”. Such gains have many sources. One textile boss got 20% more out of his seamstresses by playing background music in his factory, recalls Arnold Harberger of the University of California at Los Angeles. The striking thing about the growth in China’s total factor productivity is not its absence but its speed: the fastest in the world over the past decade. Between 2000 and 2008 it contributed 43% of the country’s economic growth, according to the APO. That is just as big a contribution as the brute accumulation of capital, which accounted for 44% (excluding information technology). Thus even if some of China’s recent investment has in fact been wasted, China’s progress cannot be written off.

And even if some of China’s past investment has been futile, adding nothing worthwhile to the capital stock, there is a consolation: it will leave more scope to invest later, suggesting that the country’s potential for growth is even larger than the optimists think. The right kind of investment can still generate high returns. But what if the mistaken investments of the past disrupt the financial system, preventing resources from being deployed more effectively in the future? from the print edition | Special report The ballad of Mr GuoWhat makes local-government officials tickMay 26th 2012 | from the print edition SINGING KARAOKE WITH Taiwanese investors, smearing birthday cake on the cheeks of an American factory owner, knocking back baijiu, a Chinese spirit, with property developers: Guo Yongchang would do anything to attract investment to Gushi, a county of 1.6m people in Henan province, where he served as party secretary. His antics are recorded in “The Transition Period”, a remarkable fly-on-the-wall documentary about his last months in office, filmed by Zhou Hao. Mr Guo persuades one developer to raise the price of his flats because Gushi people are interested only in the priciest properties. After a boozy dinner he drapes himself over the developer’s shoulder and extracts a promise from him to add more storeys to his tower to outdo the one in the neighbouring city. The one-upmanship exemplified by Mr Guo has generated great economic dynamism, but also great inefficiency. When the central government tries to stop economic overheating, local governments resist. Conversely, when the government urged the banks to support its 2008 stimulus effort, local governments scrambled to claim an outsized share of the lending. The result is a local-government debt burden worth over a fifth of China’s 2011 GDP. In this special report · The retreat of the monster surplus · »The ballad of Mr Guo The worst abuses, however, involve land. Local officials can convert collectively owned rural plots into land for private development. Since farmers cannot sell their land directly to developers, they have to accept what the government is willing to pay. Often that is not very much. Such perverse incentives have caused China’s towns and cities to grow faster in area than they have grown in population. Their outward ripple has engulfed some rural communities without quite erasing them. The perimeter of Wenzhou city in Zhejiang province, to take one example, now encompasses clutches of farmhouses, complete with vegetable plots, quacking ducks and free-range children. This results in some incongruous sights. Parked outside one farmhouse are an Audi, a Mercedes and a Porsche. Alas, they do not belong to the locals but to city slickers who want their hub caps repainted. Oddly, where electoral reforms have given Chinese villagers a bigger say in local government, growth tends to slow, according to Monica Martinez-Bravo of Johns Hopkins University and her colleagues. This is partly because elected local officials shift their efforts from expanding the economy to providing public goods, such as safe water. But it is also because a scattered electorate cannot monitor them as closely as their party superiors can. Fear of their bosses and hunger for revenues keep local officials on their toes. Mr Guo, star of “The Transition Period”, was eventually convicted of bribery. He was not entirely honest in the performance of his duties, and not always sober either. But with all the parties, banquets and karaoke, no one could accuse him of being lazy. from the print edition | Special report FinanceBending not breakingChina’sfinancial system looks quake-proof, but for how long?May 26th 2012 | from the print edition

The school that became a shrine

VISITORS TO SICHUAN’S atmospheric mountains, home to both Tibetan and Qiang minorities, used to skip Yingxiu village on their way to more scenic spots higher up. But the devastating earthquake that struck the area in May 2008 has turned the village into an unlikely tourist attraction. The earthquake killed 6,566 people in the village, over 40% of its population. Its five-storey middle school collapsed, killing 55 people. Nineteen students and two teachers remain buried in the rubble. Four years on, the crumpled school remains. It has been preserved as a memorial to the disaster, but almost every other sign of the quake has been erased. The village is full of new homes with friezes painted in strong Tibetan colours. Other buildings are topped with flat roof terraces, a white concrete triangle in each corner, echoing the white stones that adorn traditional Qiang architecture. The new homes look a little like Qiang stone houses on the outside, one villager concedes. “But inside they are all Han.” In this special report · The retreat of the monster surplus · »Bending not breaking Yingxiu is an example of “outstanding reconstruction”, according to a billboard en route. Outside this showcase village, people have rebuilt their lives with less government help. But there is no denying that China set about reconstructing the earthquake zone with a speed and determination few other countries would be able to match. A propaganda poster shows Hu Jintao, China’s president, bullhorn in hand, declaring that “Nothing Can Stop the Chinese”. The earthquake did great damage to the region’s property and infrastructure. But although it left the local economy worse off, the pace of economic activity picked up in the wake of the disaster. There was much to do precisely because so much had been lost. Even today the mountain road is lined with lorries. Some economists worry that China may soon suffer a different kind of economic disaster: a financial tremor of unknown magnitude. Pivot Capital Management, a hedge fund in Monaco, argues that China’s recent investment spree was driven by a “credit frenzy” which will turn into a painful “credit bust”. Lending jumped from 122% of GDP in 2008 to 171% just two years later, according to Charlene Chu of Fitch, a ratings agency, who counts some items (such as credit from lightly regulated “trust” companies) that do not show up in the official figures. This surge in credit is reminiscent of the run-up to America’s financial crisis in 2008, Japan’s in 1991 and South Korea’s a few years later (see chart 5), Ms Chu argues. When Fitch plugged China’s figures into its disaster warning system (the “macroprudential risk indicator”), the model suggested a 60% chance of a banking crisis by the middle of next year. China’s frenzied loan-making has traditionally been matched by equally impressive deposit-taking. Even now, most households have few alternative havens for their money. This captive source of cheap deposits leaves China’s banks largely shock-proof. They make a lot of mistakes, but they also have a big margin for error. That will help them withstand any impending tremors. But this traditional source of strength will not last for ever. China’s richest depositors are becoming restless, demanding better returns and seeking ways around China’s regulated interest rates. The government will eventually have to liberalise rates. That will make China’s banks more efficient but also less resilient. There remains great uncertainty about China’s financial exposure. Not all of the country’s “malinvestment” will result in bad loans. Some of its outlandish property developments, including the empty flats of Ordos, were bought by debt-free investors with money to burn. By the same token, not all of China’s “bad” loans represent malinvestment. Rural infrastructure projects, to take one example, are often “unbankable”, failing to generate enough income from fees, charges and tolls to service their financial obligations. But the infrastructure may still contribute more to the wider economy than it cost to provide. That is especially likely for stimulus projects, which employed labour and materials that would otherwise have gone to waste. But suppose a financial quake does strike China: how will its economy respond? Financial disasters, like natural ones, destroy wealth, sometimes on a colossal scale. But as China’s earthquake showed, a one-off loss of wealth need not necessarily cause prolonged disruption to economic activity as measured by GDP. Yingxiu suffered a calamitous loss of people and property, but this was followed by a conspicuous upswing in output (especially construction) and employment. If this seems counterintuitive, that is because GDP is easily misunderstood. It is not a measure of wealth or well-being, both of which are directly damaged by disasters. Rather, it measures the pace of economic activity, which in turn determines employment and income. Financial distress will damage China’s wealth and welfare, almost by definition. The interesting question is whether it will also lead to a pronounced slowdown in activity and employment—the much-predicted “hard landing”. To put it in Mr Hu’s terms, can a financial quake stop the Chinese? If the banking system as a whole had to write off more than 16% of its loans, its equity would be wiped out. But the state would intervene long before that happened. Despite the excesses of China’s local authorities, its central government still has the fiscal firepower to prevent loans going bad, or to recapitalise the banks if they do. Its official debt is about 26% of GDP (including bonds issued by the Ministry of Railways and other bits and pieces). If it took on all local-government liabilities, that ratio would remain below 60%. Alternatively, it could recapitalise a wiped-out banking system at a cost of less than 20% of GDP. Even if many loans do eventually sour, banks do not have to recognise these losses all at once. No loan is bad until someone demands repayment, as the saying goes. In March the government released details of a long-rumoured plan to roll over loans to local governments. Many of these loans were due to mature before the project they financed was meant to be completed. If the project is worth finishing, this kind of evergreening is an efficient use of resources. And some projects, once under way, are worth finishing even if they were not worth starting. Loan rollovers give banks time to earn their way out of trouble, setting aside profits from good loans before they recognise losses on bad ones. This task is easier in China than in other countries because its financial system remains “repressed”. Banks can force their depositors to bear some of their losses by paying them less than the market rate of interest. Indeed, deposit rates are often below the rate of inflation, making them negative in real terms. A bank’s depositors, in effect, pay the bank to borrow their money from them. Chinese banks can get away with this because deposit rates are capped by the government, preventing rival banks from offering higher rates. China’s capital controls also make it hard for depositors to escape this implicit tax by taking their money abroad. As a consequence, Chinese banks luxuriate in a vast pool of cheap deposits, worth 42% more than their loans at the end of 2011. This cash float gives Chinese banks a lot of room for error. In 2011 new deposits amounted to 9.3 trillion yuan, according to official figures, more than enough to cover fresh loans of 7.3 trillion yuan. Although deposit growth is slowing, these inflows give banks a cash buffer, allowing them to keep lending, even if their maturing loans are not always repaid in full and on time. A chronic complaint So China’s financial strains will not result in the sort of acute disaster suffered so recently by the West. Instead, they will remain a chronic affliction which the state and its banks will try to ameliorate over time with a combination of government-orchestrated rollovers, repression and repayment. Such a combination is unfair to taxpayers and depositors, but it is also stable. According to Guonan Ma of the Bank for International Settlements, bank depositors and borrowers ended up paying roughly 270 billion yuan ($33 billion) towards the cost of China’s most recent round of bank restructuring, which stretched over a decade from 1998. However, some commentators think that China will find it harder to repeat the trick in the future. Depositors are not as docile as they were. In fits and starts, resistance to China’s financial repression seems to be growing. “Let’s be frank. Our banks earn profits too easily,” Wen Jiabao, China’s prime minister, admitted on national radio in April. He is right. The ceiling on deposit rates and the floor under lending rates guarantee banks a fat margin, preventing competition for deposits and allowing big banks to maintain vast pools of money cheaply. If the deposit ceiling were lifted, small banks would offer juicier rates to take market share from incumbents. Conversely, the big banks would trim their deposit bases as they became more expensive. Households would be better rewarded for their saving, and China’s banking “monopoly” would be broken, as Mr Wen professes to want. In fact, though, the government is still dragging its feet on rate liberalisation. Its hesitancy may reflect the political clout of the state-owned banks. It may also reflect the government’s own fears. Most developing countries (and some developed ones too) that freed up their financial systems suffered some kind of crisis afterwards. Upstart firms can poach the incumbents’ best customers, threatening their viability but at the same time overextending themselves. Even in America, rate liberalisation in the early 1980s allowed hundreds of Savings and Loan Associations to throw their balance sheets out of joint, offering higher returns to depositors even though their assets were producing low fixed returns. In a 2009 paper, Tarhan Feyzioglu of the IMF and his colleagues strongly endorsed Chinese rate liberalisation. But they also acknowledged that it can be mishandled, citing America’s S&L crisis as well as even worse debacles in South Korea, Turkey, Finland, Norway and Sweden. The most famous study of these risks was written more than 25 years ago. Its sobering title was “Goodbye Financial Repression, Hello Financial Crash”. The risks of repression These are good reasons for caution, but not for procrastination. Repressed rates have their own dangers. To avoid them, savers have overpaid for alternative assets such as property, contributing to China’s worrying speculative bubble. In places like Wenzhou, a city in Zhejiang province, rate ceilings have encouraged firms and rich individuals to make informal loans to each other, bypassing the regulated banking system in favour of unsafe, unprotected intermediation in the shadows (see article). The patience of the public at large is also wearing thin. At a central-bank press conference in April, a journalist (from Xinhua, the official mouthpiece, no less) refused to let go of the microphone until her complaint about negative deposit rates was heard. A growing number of depositors are looking for ways to circumvent the ceiling. Those with lots of money to park are driving the demand for “wealth-management products”, short-term savings instruments backed by a mix of assets that offer better returns than deposit accounts. By the end of the first quarter of 2012 these products amounted to 10.4 trillion yuan, according to Ms Chu of Fitch. That is equivalent to over 12% of deposits. Most had short maturities, leaving buyers free to shop around from month to month. Banks accustomed to sitting on docile deposits may struggle to match the timing of cash pay-outs and inflows, Ms Chu frets. The banking regulator may also be worried. It has now banned maturities of less than a month. To avoid repressed interest rates, savers have overpaid for alternative assets such as property, contributing to China’s worrying speculative bubble The recent proliferation of wealth-management products amounts to a de-facto liberalisation of interest rates, Ms Chu argues. The growing competition for deposits is showing up in other ways too. When the finance ministry auctions its own six-month deposits, banks are now willing to offer rates as high as 6.8%, more than twice the maximum they are able to offer to ordinary depositors. The government may seek to formalise this de facto liberalisation, gradually allowing banks more freedom to set rates on large long-term deposits—the kind that will otherwise disappear from banks’ books. Net corporate deposits, for example, did not grow at all in 2011. Higher rates would help attract them back. That would also raise banks’ costs of funding, forcing China to become more efficient in its allocation of capital. At the moment the system is segregated between big enterprises, which enjoy relatively low borrowing costs, and credit-starved private firms that could potentially earn much higher returns on investment. In a freer financial system, competition would begin to close this gap. If interest rates went up to match the return on capital, Chinese investment would fall by 3% of GDP, according to a study by Nan Geng and Papa N’Diaye of the IMF. More flexible interest rates would also raise Chinese consumption, says Nick Lardy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. He calculates that if banks paid something resembling a market interest rate on their vast deposits, household income would increase by 2% of GDP. Higher incomes, he argues, would cause their spending to rise and their saving rate to fall. The ideathat higher rates will make people save less is unorthodox, but Mr Lardy argues that the higher income from saving will have a bigger effect than the higher reward offered for it. Chinese households save towards a goal, he suggests, such as the down-payment on a house or the cost of a potential medical emergency. Lower the return to saving, and they will just save even harder to achieve their goal. Research by Malhar Nabar of the IMF suggests that higher interest rates would indeed bring down saving rates, but the effects would be modest. If the real rate on one-year deposits rose from roughly 0% today to a more reasonable 3%, it would lower household saving by only about 0.5% of GDP, he calculates. But if higher interest rates alone will not liberate Chinese consumption, what will? from the print edition | Special report · Recommended · 11 The next chapterBeyond growthChina will have to learn to use its resources more judiciouslyMay 26th 2012 | from the print edition

Still plenty of room to grow

THE POLICYMAKERS WHO will determine China’s future are trained at the Central Party School, a spacious oasis of scholarly tranquillity in north-west Beijing. The campus looks like an Ivy League school with Chinese characteristics. The grounds are dotted with stiff bamboo as well as pendulous willows, pagodas as well as ducks. The school remains largely closed to outsiders. In the past it did not even appear on maps. But it is opening up. The campus signpost, for example, is sponsored by Peugeot Citroën. The school has over 1,500 students and almost as many professors, many of whom are much younger than their students. It teaches economics, public finance and human-resource management as well as communist doctrine, such as Marx’s labour theory of value. It takes only three or four classes to teach Deng Xiaoping Theory, the party dogma that legitimised China’s economic reforms and still guides its Politburo. But if even that is too much, three famous clauses may suffice: “Our country must develop. If we do not develop then we will be bullied. Development is the only hard truth.” In this special report · The retreat of the monster surplus · »Beyond growth Deng said these words 20 years ago, not at a portentous party conference in Beijing but on his “southern tour” of the workshops of the Pearl River Delta. He was inspired by practice, not theory, having just visited a refrigerator factory in the delta that had expanded 16-fold in seven years. Even the word he used for truth (daoli, which is often translated as reason or rule) is more colloquial than the loftier term, zhenli, reserved for high truths like Marxism-Leninism. Giants playing catch-up Thanks to a sevenfold rise in its output since then, China is well past the point of being bullied. Its dollar GDP, measured at purchasing-power parity, may have already overtaken America’s, according to economists such as Hu Angang of Tsinghua University or Arvind Subramanian of the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Converted at market exchange rates, it is still much smaller than America’s. But even by that measure, China may catch up sooner than many people currently expect. To draw level with America by 2020, China’s dollar GDP would have to grow at only about three-quarters of the average rate it recorded over the past decade. Now that China has become too important to be bullied, development may be less of an imperative. Indeed, in some quarters of society there is an increasing distaste for the unwelcome side-effects of China’s growth model, which depletes the country’s natural assets at the same time as it expands its physical ones, and which builds lots of property but often bulldozes property rights. Some party elites and vested interests may also have grown complacent, worrying more about how to divide the economic spoils than how to enlarge them. But at least in their rhetoric, leaders do not appear to be resting on their laurels. Asked about China’s prospects of becoming the world’s number one economy, Li Wei, head of the Development Research Centre, which advises China’s cabinet, saw no reason to celebrate. The country’s income per person still ranks around number 90 in the world. And even if its GDP overtakes America’s by the end of the decade, China will remain as poor as Brazil or Poland are today, by one estimate. Hubris may be less of a danger than its opposite, a kind of economic diffidence. If China is still poor in the minds of policymakers, they may conclude that the economy is not yet ready for reforms that are in fact overdue. They may feel that a poor developing country does not need a more sophisticated financial system, cannot cope with a more flexible exchange rate and cannot afford to let its rural masses settle in the cities with their families. As long as the demand for investment remains strong and the supply of saving captive, China’s policymakers can feel confident that their country’s economy will continue to enjoy rapid growth and stability. But the faster that China expands, the sooner it will outgrow the development model that has served it so well for so long. Japan began to change its growth model back in the mid-1970s. By some measures China has already reached a similar stage of development, and yet its reforms remain tardy and timid. School rules There are at least three schools of thought on China’s economic prospects over the next few years. The first sees few dangers ahead. China has expanded quickly, always beating forecasts, and will continue to do so for the time being. It is a huge, fast-developing country with plenty of room yet to grow. It invests a lot—and so it should. These investments might not always generate good returns for the bankers that lent the money. But they will contribute more to the economy than they cost. The second school of thought argues that China’s imbalances could overwhelm it. It cannot sustain its current high rate of investment, but there is nothing else to replace this as a source of demand. Much of the credit extended by banks and shadow banks to keep growth going will sour. A government that owes its legitimacy entirely to growth will find it hard to contain the disappointment that a slowdown will entail. This special report subscribes to a third school of thought. It argues that China does face significant problems, but nothing it cannot handle. It has not obviously overinvested, but it has often invested unwisely. That is imposing real losses on Chinese developers, depositors and taxpayers. However, China’s financial system is better equipped than many others to ride out these losses. It may be inefficient in its allocation of capital, but it is quite stable. Indeed, it is resilient for some of the same reasons that it is inefficient. “Our country must develop. If we do not develop then we will be bullied. Development is the only hard truth” Until recently most economists believed that China was heavily dependent on exports. But it has carried on growing even as its current-account surplus has shrunk, and trade has subtracted from growth, not added to it. The country is undoubtedly investment-dependent, but its biggest problem is malinvestment not overinvestment. Most people believe that its past malinvestment will impede future growth. This special report has raised doubts about that. Clearly China would be better off had it not wasted so much capital. But if the capital stock is not as good as it should be, that gives the country all the more room for improvement. If the investment rate does fall, China will need another source of demand. The obvious place to look is household consumption, but consumers may not rise to the challenge. This special report has argued that a much higher rate of government consumption would be equally desirable—and perhaps more feasible. As China’s capital accumulates, its population ages and its villages empty, saving will grow less abundant and good investment opportunities will become scarcer. China will then need to use its resources more judiciously. That will require it to free up its financial system, introducing more efficiency even at some cost to stability. China is a vastly more prosperous and expansive country than it was 20 years ago. It has broader horizons and can afford a wider range of concerns. Development is no longer China’s only truth. But it is still hard. from the print edition | Special report Daily chartChina in your handMay 25th 2012, 13:10 by The Economist online A brief guide to why China grows so fast OUTSIDE China, people tend to assume that the countrys impressive economic growth is due to exports. As the chart below, drawn from our special report on Chinas economy, shows, this notion has always been exaggerated and is now plain false. China grows thanks to high levels of investment—far higher than those seen in previous Asian miracles such as South Korea and Japan. The corollary of this is low levels of private consumption. Some argue that this must lead to imbalances that one day will send Chinas economy off a cliff. We disagree.

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |