字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/04/13 08:10:25瀏覽46|回應0|推薦0 | |

The Bo Xilai caseShattering the façadeApr 14th 2012 | BEIJING AND CHONGQING| from the print edition

WHEN the axe fell, it was sharper than expected. Ever since the unexplained dismissal last month of the Communist Party chief of Chongqing, Bo Xilai, rumours had swirled about his family’s alleged wrongdoings. On April 10th the government broke its silence, accusing Mr Bo of “serious”, though still unspecified, wrongdoing and, more startling, making Mr Bo’s wife a suspect in the murder of a British businessman. The political career of Mr Bo, one of China’s most prominent politicians, appears to be over. The risk of further political turbulence in China is not. Mr Bo’s case has created the most damaging split in the party leadership since the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. The allegations against him and his wife appear to have given other leaders resentful of his ambition and populist approach the pretext they had long sought to bring him down. The government’s announcement declared that Mr Bo had been suspended from his membership of the ruling Politburo and the party’s Central Committee. It said the party would investigate his suspected “discipline violations”. In this section · »Shattering the façade Since Tiananmen, the party has jailed two other politicians who had served as Politburo members: one in 1998 and the other a decade later, both on corruption charges. But Mr Bo has a high profile, charisma and popularity (especially inChongqing) as well as family pedigree (his father was a notable revolutionary) and powerful allies. That is why this struggle was so exceptional. Even after his dismissal from his post in Chongqing on March 15th, some believed Mr Bo might retain his Politburo seat until a shuffle of the top leadership at the end of the year, or possibly longer. That the party kept silent for four weeks before delivering any explanation of Mr Bo’s sacking suggests that leaders were divided over how to handle him. It remains unclear whether criminal proceedings will be launched against Mr Bo himself. But the government says that his wife, Gu Kailai, and a family employee, Zhang Xiaojun, have been detained for the suspected murder of Neil Heywood, a British businessman who died in Chongqing in November. Ms Gu and the Bos’ son, Bo Guagua, the government alleges, had been on “good terms” with Mr Heywood, but fell out over unspecified “economic interests”. The younger Mr Bo is studying at Harvard University, one of many details of the Bo family’s privileged lifestyle that China’s internet users have been picking over with horror and glee since the scandal first broke (the 24-year-old also chugged around Beijing in a Ferrari). The alleged connections between Mr Heywood’s death and the Bo family surfaced in the foreign media in late March. It is now clear that Wang Lijun, once deputy mayor and police chief of Chongqing, had suspicions when he fled to the American consulate in the south-western city of Chengdu on February 6th. During his 30 hours inside the consulate, Mr Wang told the Americans that he had been dismissed as police chief after confronting Mr Bo with his suspicions of a link between his boss’s family and Mr Heywood’s death, and that he feared for his own life. Although Mr Wang sought the protection of the Americans, it was made clear to him that passage to the United States and potential asylum there were out of the question. Huang Qifan, the mayor of Chongqing, who has kept his job throughout the scandal, was allowed into the consulate for a private meeting with Mr Wang, who later walked out on his own into custody. Mr Wang’s flight to a foreign mission was extraordinary for somebody of his celebrity (as a fighter of organised crime) and rank (equivalent to that of a deputy provincial governor). The episode spurred its own investigation by Beijing. Some analysts doubt if Mr Wang would have dared to take the issue of Mr Heywood’s death up with Mr Bo unless other circumstances had compelled him. Either way, the authorities’ unusual handling of the death (which the Chongqing police initially ascribed to overdrinking) may, some say, be a sign of high-level struggles. Mr Bo’s opponents (presumably led by President Hu Jintao and the prime minister, Wen Jiabao) have shown unexpected strength by purging Mr Bo so thoroughly. But their battle is not over. Mr Bo was much loved by a “new left” force in Chinese politics which admired his big spending on public welfare, especially social housing, and his fondness for state-owned enterprises. On April 3rd Mr Wen expressed unusual frustration with the state’s grip on the financial system, saying the state banks were a “monopoly” that must be broken. Progress, however, will be tortuous, notwithstanding the battering the left has suffered as a result of Mr Bo’s fall. Powerful interests, especially state firms, remain an obstacle. Political reform, which Mr Wen has repeatedly called for, is even less likely to make headway in the months ahead. Officials are fearful of any adjustment that might upset stability before this year’s leadership changes. Much mess is left to be cleared up in Chongqing. Mr Bo’s crackdown on crime, although widely admired by ordinary Chinese, created suspicions among private businesspeople. They thought that he was looking for ways to seize their assets so as to use them for more public spending. One property now in the Chongqing government’s hands is a 20-hectare (50-acre) villa and golf-course development, with a near-finished Hilton hotel. Its former owner (as well as of another Hilton in central Chongqing), Peng Zhimin, was jailed for life last year for various offences, including bribery and prostitution. It remains unclear how the government will dispose of this vast, confiscated wealth. Mr Bo’s enemies will be relieved that, so far, his demise has not stirred a public backlash. Hundreds of riot police were deployed on April 10th-11th to put an end to violent demonstrations by citizens protesting against the merger of two Chongqing districts, but the unrest appeared to be unrelated to Mr Bo’s departure. A lawyer in Chongqing says two elderly people displayed a slogan last month expressing support for Mr Bo, but were whisked away by police (and later released). On April 6th the authorities in Beijing shut down some pro-left websites that had been publishing articles supporting him. In a commentary on the Bo case, couched in old-time Leninist rhetoric, the party’s main mouthpiece, the People’s Daily,called on citizens to maintain a “high level of ideological unity” with the party and with Mr Hu. Mr Bo’s critics often accuse him of having tried to crush any who opposed him. Those who now have the upper hand in the struggle appear to be brooking no dissent either. from the print edition | China 筆者寫上述文章的回文並且參考了這兩篇 Bo Xilais political demise Downfall, part twoApr 11th 2012, 3:03 by T.P. | BEIJING

WITH plot twistsworthy of a Chinese version of Macbeth, Communist Party officials announced late Tuesday night that disgraced politician Bo Xilai had been suspended from all his political duties, and named his wife as a suspect in the murder last year of a Briton living in China. Mr Bo “is suspected of being involved in serious discipline violations” and will be formally investigated, according to a terse report released around 11pm by multiple state- and party-run media outlets. The Communist Party Central Committee had decided to “suspend” Mr Bo’s membership in that body, and in the more elite Political Bureau. A month ago, Mr Bo was removed from his post as party boss in Chongqing, a province-level municipality in south-western China. A separate and more detailed announcement carried at the same time said that Mr Bo’s wife, Gu Kailai, together with a household staffer, was “highly suspected... of intentional homicide” in the death in Chongqing of British businessman Neil Heywood. When Mr Heywood was found dead in a Chongqing hotel last November, authorities initially determined the cause to be an alcohol overdose. But yesterday’s announcement said that after a “reinvestigation” the case has been deemed a homicide. The report said that both Gu Kailai and the couple’s son were on “good terms” with Mr Heywood, but that conflicts over economic interests had intensified. Ms Gu and the household staffer, named as Zhang Xiaojun, had already been transferred to judicial authorities, the report said. The couple’s son, Bo Guagua, is currently enrolled as a university student in America and is thought to be there now. He had previously studied in Britain at some of the nation’s most prestigious private schools. Until this year, Mr Bo, the son of a revered early Communist revolutionary, seemed on track for advancement to the highest levels of leadership. Before taking up his post in Chongqing, Mr Bo had served in a variety of senior jobs, including Minister of Commerce and governor of Liaoning Province. He was among the most colourful of senior Chinese leaders, openly cultivating public support. He also spearheaded controversial and high-profile political campaigns against corruption and organised crime, and in favour of old-line Maoist slogans, songs and sensibilities. The first public sign of high drama surrounding Mr Bo and his family emerged in February, when his close deputy, Wang Lijun, entered the American consulate in Chengdu, the capital of neighbouring Sichuan province, in what appeared to be an attempt at gaining asylum. He spent a full day there before being taken into custody by central-government authorities. Tight-lipped American officials would only say that he left the consulate "voluntarily". In March, at the close of the annual session of China’s National People’s Congress, Mr Bo was the recipient of public and thinly veiled criticism from the prime minister, Wen Jiabao. A day later, he was removed from his post as leader of Chongqing. The drama has raised important questions about what the case might mean for the delicate equilibrium between the multiple factions at the top tier of Chinese politics. It has been six years since a leader of Mr Bo’s stature has been suspended, and the precedents established over the past 30 years suggest Mr Bo has no viable path to any kind of political rehabilitation. But he does retain a substantial following, both among the public and within political circles. Beyond his more flamboyant politicking, Mr Bo was appreciated as a provider of social welfare benefits to the masses who have found themselves on the losing end of China’s market reforms, and the reaction of his supporters to the latest developments will be something to watch. The timing is especially sensitive because of the once-a-decade leadership transition scheduled for later this year. Ever fixated on maintaining stability—or at the very least the appearance of stability—the Communist Party had hoped that the transition process would play out more smoothly than this. (Photo credit: AFP) Models of developmentChongqing rolls onA city’s deposed leader had tried to be different. But was he?Apr 28th 2012 | CHONGQING | from the print edition

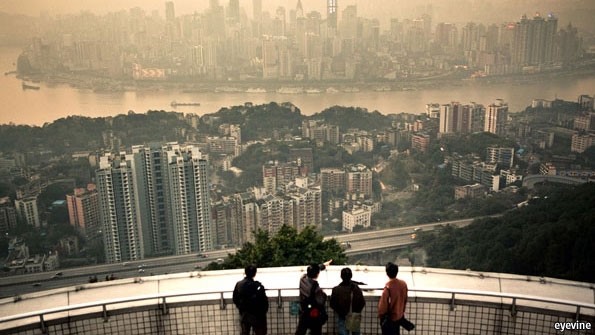

LIKE many local governments in China, Chongqing’s has an exhibition hall devoted to its dreams. Its scale models show an urban core sprawling outwards with thickets of new apartment blocks: cheap housing for the masses built at vast government expense. Bo Xilai, who governed the region’s 30m people, 5m of them in Chongqing city, made big spending on public works his hallmark. His purge was seen in some quarters as the result of a struggle between two competing models of governance: the “Guangdong model”, in which economic liberalism is matched with pragmatic decision-making, and the “Chongqing model”, emphasising the importance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and traditional socialist values. But the Chongqing model trumpeted by Mr Bo’s supporters was by no means unique to Chongqing. Nor is it dead. In closed-door meetings and in veiled attacks in the media, Communist Party officials have been heaping opprobrium on Mr Bo and members of his family. Their aim, it appears, is to make allegations stick that the Bos were corrupt and that his wife was complicit in the murder of a British businessman. A New York Times report claiming that Mr Bo wiretapped phonecalls between China’s president Hu Jintao and senior officials visiting Chongqing reiterated the fact that Mr Bo is now politically finished. But many of his economic policies, though the subject of a bitter dispute between the two ideological camps, will probably prove resilient, for they are more in line with party doctrine, or at least common practice, than either camp admits. In this section · »Chongqing rolls on Related topics · China Mr Bo and his officials avoided using the term “Chongqing model” to describe the south-western region’s formula for securing such accolades as one of the fastest-growing provinces or provincial-level regions in the country (at 16.4% last year) and, more controversially, one of China’s happiest places (in some state-media surveys). But even after Mr Bo’s sacking on March 15th, government-owned bookshops in Chongqing continued to stock books that discuss the model and Mr Bo’s role in implementing it. Liberal scholars in China have delighted in picking apart Mr Bo’s policies, which they characterise as a lurch back towards Maoism. Their harshest attacks have been on his attempts to revive “red culture” by encouraging the singing of revolutionary songs and on the brutal methods (if not the aims) of his crackdown on organised crime. But state-controlled media have shown far more restraint. This might reflect differences among Chinese leaders over how to assess Mr Bo and his leadership of Chongqing. But it is also likely that even Mr Bo’s enemies in Beijing worry about launching an assault on his policies, for fear that it might encourage criticism of the central leadership’s own economic strategy. Much of Mr Bo’s approach took root under the leadership of his predecessor, Wang Yang, who went on to become party chief of Guangdong province (and champion of the Guangdong model). Mr Wang is widely expected to join the Standing Committee of the Politburo later this year (a spot Mr Bo coveted). Mr Bo’s chief economic strategist, Chongqing’s mayor Huang Qifan, was a strategist in both administrations. He remains in office and seems still to be engaged in policymaking. Mr Bo’s strongest supporters are diehard Maoists and members of the so-called “new left” who believe that China has strayed too far towards Dickensian capitalism. But this group has projected onto Chongqing an image of communist rectitude that does not fit the reality of the region’s development nor Mr Bo’s own proclivities. As one foreign businessman put it, Mr Bo would “signal left but turn right”. Jiang Weiping, a Chinese journalist who was jailed for five years after writing articles critical of Mr Bo, and is now living in Canada, calls him an “opportunist”.

Take, for example, his much-touted admiration for SOEs. Mr Bo was quoted in 2010 by state media as saying that China should not import Western-style ways of doing business based on pure private ownership. “We need to have things that are state-owned,” he said. Mr Huang, the mayor, has boasted of a sixfold increase in the net value of state assets in Chongqing between 2003 and 2009. But the private sector has grown vigorously too. Its share of Chongqing’s GDP rose from about half in 2005 to more than 60% five years later, roughly the same as the national level. One of Mr Huang’s strategies has been to lean on SOEs to boost the region’s coffers. Chongqing officials say local state firms have given 15-20% of profits to the government in the past five years, and that this will increase to 30% by 2015. Mr Huang has described the rate of contribution of SOEs to government revenue in Chongqing as the highest anywhere in China. Officials say this has enabled Chongqing to keep its business tax at 15%, compared with 25% elsewhere, and spend more on “people’s livelihood”. Though liberal economists in Beijing wince at Chongqing’s embrace of SOEs, they too have been calling for much higher payouts from them as a way of boosting funds for welfare. Some Chinese economists wonder how long Chongqing can continue spending as much as it does without piling up crippling debts. The planning exhibition showcases Chongqing’s “ten big cultural facilities” (begun before the arrival of Mr Bo): lavish buildings of Pyongyang-style pomposity, including a “grand theatre” second only in size to Beijing’s. These have cost Chongqing a total of more than $1.5 billion so far. That is small beer, though, compared with the $7.6 billion spent by Mr Bo on a “Green Chongqing” campaign that has included mass tree-planting, in which some trees have ended up dead, locals say, because of the unsuitable climate. But Chongqing’s spending is nothing unique. China is littered with wasteful “image projects” built by local chiefs. Central leaders may condemn some of Mr Bo’s extravagance, but they will tread carefully when it comes to his most conspicuous outlay: $15 billion for 800,000 apartments to be rented out cheaply to the poor. Chongqing’s rapid implementation of this colossal undertaking, beginning in 2010, led the central leadership to argue for similar projects nationwide. This was seen not just as a way of keeping the poor happy, but of shoring up China’s economy during the global downturn. The scheme’s shortcomings are obvious in Chongqing, just as they are elsewhere. In one newly built cluster of apartment blocks a resident complains that a trip to the city centre takes two hours by bus. There are few shops, and many of the apartments are still empty, he says. At another new development, farmers nearby say they had to surrender their farmland to make way for construction and were not properly compensated. Mr Bo may have talked like a leftist, but his tactics for getting work done fast and keeping the money rolling in would be familiar across much of China. He has bent over backward to court foreign investors. He offended his leftist allies by approving a multi-billion dollar chemical project involving BASF, a German firm. Much of Mr Bo’s economic strategy has been explicitly encouraged by the central leadership. In the end, in a party that prides itself on consensual, colourless leadership, it was Mr Bo’s highly visible efforts to boost his public image that hastened his undoing. Chongqing itself will carry on. from the print edition | China

提到這個越來越淡忘的事件,最近因為幾件人事案及習近平是否算有對於下一代領導人作部署而又被人提及。薄的左右手,王立軍的另一位,劉偉,被調回北京而重慶市長即將可能由唐良智,習近平可能的親家接任。重慶從1999年升格至直轄市已經換了至少五批政治領導了。今天(2019/04/21)離這篇一開始貼這篇有近一年,想起來回憶一番。今次過年後不久求證過這是可靠的消息,唐良智就是三立新聞主播曾鈴媛的表舅,很有趣,她說綽號湯圓的的諧音第一個字是她母親的姓。 薄熙來的暗殺外國前記者及商人的醜聞是在2011年11月14日,牽扯到的有該死者英國人Neil Heywood,薄谷開來和薄瓜瓜,以及跑至美國駐重慶總領事館過的王立軍。這個刑案是造成隔年三月後,曾一度被稱作「中國的馬英九」的薄熙來直接被中共中央雙開的原因。這次的政治鬥爭不同於以往從高崗還是王洪文、陳希同的政治路線之爭、派系傾軋的被批鬥,是就政治現代化來說的必要之惡。當年中央是全體無異議通過,並且嚴查、公開審理,之後的周永康的瑯鐺入獄,和令計畫的叛逃問題,都是薄案的延伸。 這件事確立了習李二元體制,也穩定了太子黨的統治基礎。太子黨是從江澤民由鄧小平和李鵬確定權威後,在作接班人選定時,原先不希望由黨內的功業或政績來評比,覺得比較不認識不放心,遂由心腹曾慶紅,在鄧小平有決定第四代領導是胡錦濤、溫家寶之後,第五代的順位是考慮對台的政治作戰,給了習近平和李克強作領導,習的班底是習在浙江、福建近二十年的工作的「之江新軍」、他父親的舊識,及在國務院國防部任職所認識的軍官或官員。曾經有所謂「新太子黨」說法,是指胡和溫的附近的官員的下一代,以其子胡海峰為首的安徽幫的紅二代地方官為主。本來以為就是一直是習和附近的官員作升遷,在孫政才被捕後,曾經被認為的陳敏爾或是胡春華在修憲後的政治地位也沒有人作多加揣測。幾乎沒有認為習會在有生之年決定接班人選,直到最近從北京的官媒傳出胡海峰的地方政績作討論,並被認為在趙樂際的趙家軍在陝西有涉貪舞弊後,要接任西安市委書記,一般說來是回到了接近中央官員的升遷路上,又起了一波對習近平接班人的熱議。 筆者當年回答於經濟學者的討論區如下文 Shattering the façade Apr 17th 2012, 16:52 This bomb exploded shortly before Xi Jin-Ping’s foreign visit about two months ago. Already, Bo nowadays becomes “has-been” instead of his actively dominant role among China’s Communist Party (CCP) for past several years. Bo leaves endless sorrow with international media’s camera, especially Time Magazine which has seen as the mainstream in CCP’s fifth generation with Xi, the successor as president in 2013.

I, an affiliation of CCP’s Youth League (CCYL), just coldly watched this war on another side of river from the start to the presence. What lets Bo terminate his ambition is the decision made by a discipline committee, which results from Wang Li-Jun’s geek behaviour. In my opinion, Wang Li-Jun was so sensitive that he mistook the occurrence of “knockdown”. Last November when I talked with Bo, Bo expressed the willing to promotion. So I feel that clumsy Wang followed the wrong boss only to have me send Buddhist “O-Mi-Tuo-Fou” to Wang Li-Jun and Bo Xi-lai’s couple. Until now, rumors has it that Bo wants to become the strongest in China. More scandal let out about Bo’s wife, Gu Kai-lai, an Englishman and housekeeper; moreover, I heard of many strange things entangled, letting me see Bo’s faction as gay-like gangsters, when Wang Yang told me these miserable cause. Oh! Bo’s followers are “The Full Monty”!

In fact, there are several well-known figures, classified as princeling party for discussion, including vice premier Wang Qi-Shan, vice foreign minister Wang Guang-Ya, Taiwan Affair’s Wang Yin, State Council’s Dai Bing-Guo and General Liu Ya-Zhou. Except for Wang Yin, I knew these officers along with Xi and Bo very much. There are the similar ones joining politics in Taiwan, like Taipei mayor How Long-Bin, a son of former premier How Bou-Tsuan, and Chen Chi-Chong, a son of former president Chen Shui-Bian and a Jaguar’s fan as Bo.

As I once replied on Economist last June, I never think that Bo could enter into the core while involving Taiwan affairs under Beijing’s leadership for last decade. I knew many frenzy interior and foreign fans, full of fantastical image, who supported Bo for kicking out the corruption and his hard work in development of Mao’s value, but this kind of fans showed too much ecstatic applause to Bo. For nearly four years, some foreigner officers, from Portugal and some Europe’s, had written “optimistic” praise for “Chongqing Experience”. Furthermore, Taiwan’s some Kuomintang members saw Bo as “China’s Ma Ying-Jeou”.

I don’t mean that these fans had no reason for supporting Bo. Yeah, a decade ago, I was a fan of Chen Shui-Bian in Taiwan while I support one-China principle under CCYL’s Li Ke-Qiang. (Yes, there was once a buffer of my political thoughts.) Well, Bo had strong public charisma in China. At the first decade of Bo’s career in Liaoning, Bo often conflicted with his colleagues in fighting. But his aggression got Jiang Ze-Min’s admiration so that he won promotion to Liaoning’s governor with reputation.

As a whole, Bo pushed many economics dictation, emphasizing the mixation of multiparty system by Mao’s logic and fair economic surroundings with his good use of master degree of journalism. Furthermore, Bo’s dictation sounds splendid for China’s politics, but Bo, hard to put forward a constructive plan, lacked the notion of a clear definition in addition to the alienation of fifth-generation CCYL (just a bit serious for us). Also, as I once posted on Economist, Hu Jing-Tao criticized Bo who offended Hu’s principle of “scientifically practising politics” and, many times, claimed Bo’s “awfully weird” behaviour would hinder the progress of society as well as endanger the safety of CCP and nation’s politics. Finally, Hu took this chance to cross out Bo from Polituburo.

Actually, some CCYL’s figures, who features in China’s contemporary politics, do more excellent than princeling party. Bo’s dictation and ability can be substituted for Wang Yang and Li Ke-Qiang’s ability to organize the bureaucracy. Wang is now supported by massive Chinese blogger and trying to hold moderate election in Guangdong - “Guangdong Model” - while Li got some idea of democratic notion from Taiwan’s Chen Shui-Bian and respected Li’s colleagues’ profession including mine. Really, I can even disclose that People’s Liberation Army intends to support these two. Both indeed need international focuses and occupation in newspapers for their better performance than Bo and Xi’s. Alas, I feel pity for unfair international media due to the wrong message really except for you, The Economist, that I am really grateful to.

Needless to say, as many media reported, there’s a great unity and solidarity in CCP’s core after “optimizing”. With the song “clover”, sang by Avex’s hiro, I feel fortunate when nothing inauspicious falls foul of me and CCYL these months, thanks to dropping number of princeling party and recovery of CCYL. I, mimicking Doctor Black Jack, assist with Beijing for being world’s superpower.

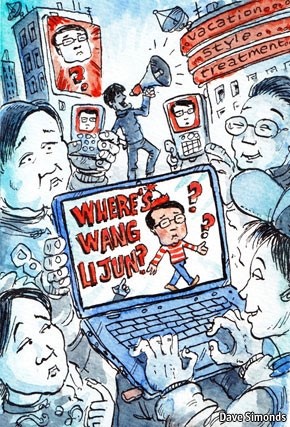

Recommended 5 Report Permalink *附王立軍出逃事件第一週經濟學者的二月報導兩篇: Reporting Chinese politicsHidden newsThe rumour mill goes into overdriveFeb 11th 2012 | BEIJING | from the print edition

IN AN earlier era, it would have been the sort of scurrilous rumour picked up by scandal sheets in Hong Kong but only whispered in Beijing: the high-profile right-hand man of a prominent Politburo member gets wind that he is about to be cashiered by the authorities and flees to an American consulate seeking protection (fate unknown). Even 15 years ago, most of mainland China would have heard nothing and Chinese officialdom could have remained comfortably silent. Today such rumours, scurrilous or not, are not so much whispered as bruited by megaphone by Chinese citizens themselves, via websites and microblogs. Chinese-language news outlets and websites based in America and Hong Kong, many of them notoriously unreliable, now have a potential audience of hundreds of millions for their political gossip, and just as many possible sources. More than 300m Chinese internet users have at least one microblog account, and some use virtual private networks (VPNs) to get around the infamous “great firewall” of China. The Chinese government is being dragged, click by click, out of its cone of silence. In this section · »Hidden news So it is with the drama of Wang Lijun, once celebrated as the mob-busting police chief of the south-western metropolis of Chongqing. Mr Wang also serves as a deputy mayor under the city’s ambitious party boss, Bo Xilai, who may join the all-powerful standing committee of the Politburo this year. On February 1st Mr Wang was shuffled to other duties in Chongqing. The next day Mingjing News, a website in New York which trades in gossip about the Chinese leadership, reported that Mr Wang was under investigation for corruption. The report initially drew only minor notice among China-watchers. That changed on the night of February 7th, when netizens reported, via Sina Weibo, a Twitter-like microblog service, a heavy police presence outside the American consulate in the nearby city of Chengdu. From this thin reed of fact came a thicket of online rumours that Mr Wang had fled to the consulate to seek asylum. It turns out he did go to the consulate, meeting officials “in his capacity as vice mayor”, according to America’s State Department. He walked out of his own accord. On February 8th the Chongqing authorities chose to speak up. Mr Wang, they said on their microblog, had health problems, and was receiving “vacation-style treatment”. The statement was retweeted more than 30,000 times within an hour. One person who seized on the phrase was Li Zhuang, a lawyer who served 18 months in prison after defending a gangland boss arrested in a crackdown orchestrated by Mr Wang. “I would like to offer free legal advice to all the ‘sick people’ who are having vacation-style treatments,” he tweeted. Censors seemed unable or unwilling to block the flood of joking and commentary. Ho Pin, who publishes Mingjing News, thinks the flood is unstoppable. “There’s unprecedented support for exposing the rich and powerful,” he says, which means watching Chinese politics may become more enjoyable—unless you are an official. What really happened at the American consulate in Chengdu? And what has become of Mr Wang? In the absence of a detailed official statement, many will be keeping an eye on another China-watching website, Duowei Newsbased in America. It was founded by Mr Ho but is now under new management. In July Duowei was first to debunk a report that Jiang Zemin, a former Chinese president, had died. China’s official news service, Xinhua, quashed the rumour the following day. Gathering news about Chinese leaders remains a risky business, especially if the news is accurate, when it is open to the catch-all charge of “revealing state secrets”. No surprise perhaps that the office inside a vast office complex on the outskirts of Beijing that apparently houses Duowei’s China bureau has no brass plate in the lobby; the man inside refused to greet The Economist. The Hong Kong media mogul who owns the website, Yu Pun-hoi, also declined to be interviewed, saying that Duoweiis “a very small business”. Its business—the news of Chinese politics—is, however, only going to get bigger. from the print edition | China China’s princelingsGrappling in the darkA cloud descends over the Communist Party’s succession plansFeb 18th 2012 | BEIJING| from the print edition

ON HIS visit to America this week China’s vice-president, Xi Jinping, serenely played the role his aides had scripted for him as the country’s leader-in-waiting, charming his hosts but revealing little (see Lexington). At home, however, the Communist Party’s plans for a sweeping shuffle of its hierarchy later this year were beginning to appear less orderly. There remains little doubt that Mr Xi will take over from Hu Jintao as party chief at a five-yearly congress to be held sometime in the autumn. But the prospects of another aspirant to top office, Bo Xilai (pictured above), have been overshadowed. On February 6th his one-time right-hand man, Wang Lijun, fled to the American consulate in the city of Chengdu. Mr Wang stayed inside for a day before walking out into the hands of Chinese security officials, who are believed to have taken him to Beijing. In this section · »Grappling in the dark Little is known about what prompted Mr Wang to make the 340km (210 mile) drive to Chengdu from Chongqing, a province-sized municipality where Mr Bo, known as an urbane populist, is party chief and the dour Mr Wang is a deputy mayor. Most analysts believe that Mr Wang’s removal from his other post as police chief five days earlier signalled a falling-out between the two men. One popular explanation for this is that Mr Bo wanted to distance himself from Mr Wang, who—rumour has it—was being investigated for corruption. So far, Mr Bo has appeared unruffled. He attended a scheduled meeting on February 11th with Canada’s visiting prime minister, Stephen Harper, as well as gatherings of senior officials. But if, as is possible, Mr Wang tries to defend his actions by claiming persecution and by levelling accusations against Mr Bo, or if Mr Wang turns out not to be the superhero policeman of his public image, the case would have big political ramifications. Mr Bo is a former minister of commerce and considered to be one of China’s more charismatic senior leaders. Before last week, he was thought likely to be promoted to the Politburo’s nine-member standing committee in the autumn. His failure to gain a seat would be a blow to two influential political camps. One is a group made up of the “old left” who lament the passing of Maoism, and the “new left”, who want to restore some of Mao’s more worker-friendly policies. This group extols Chongqing as a model of the way the country should be run. It admires Mr Bo for his heavy spending on social housing and on education and health care for migrants. The old left likes Mr Bo’s attempts to revive “red culture”, including the singing of old revolutionary songs, and his fierce campaign (carried out by Mr Wang) against corruption and organised crime. The other, more disparate, camp is that of “second-generation reds”, as the offspring of old revolutionaries are often called. Mr Bo is one of the most prominent and charismatic of these “princelings”, as they are more disparagingly known. (Mr Xi also belongs to this group, though it is unlikely that Mr Bo’s troubles would affect him.) Kenneth Lieberthal of the Brookings Institution, an American think-tank, says it is possible that leaders at the top are trying to rein in Mr Bo because they do not like his very public grandstanding. Liberals in China are crowing over Mr Bo’s plight because of what they see as his trampling on legal procedures during his anti-mafia campaign, as well as the chilling reminders his “red songs” convey of Mao’s totalitarianism. But party leaders in Beijing will have to tread carefully. They do not want wider questioning of the princelings’ right to rule. And they do not want to precipitate unrest. Mr Bo is popular in Chongqing, and more broadly elsewhere among the urban poor. The old left command loyal, if scattered, followings among workers laid off from state-owned enterprises in many cities. Maoist websites in China have been fuming about what they describe as attacks by unnamed “treacherous officials” on Mr Bo and Mr Wang. Chinese leaders have another good reason to keep the lid on their differences. The last succession process a decade ago was the first orderly one in the history of Communist Party rule in China. The party is eager to convince the world that power transfers have become a smooth ten-yearly routine. It has dismissed Mr Wang’s bizarre dash to the consulate as an “isolated” incident. Officials are doubtless relieved that their American counterparts are keeping quiet about what they learned during Mr Wang’s visit. from the print edition | China

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |