字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/04/13 08:06:57瀏覽36|回應0|推薦0 | |

The dragon’s new teethA rare look inside the world’s biggest military expansionApr 7th 2012 | BEIJING | from the print edition

AT A meeting of South-East Asian nations in 2010, China’s foreign minister Yang Jiechi, facing a barrage of complaints about his country’s behaviour in the region, blurted out the sort of thing polite leaders usually prefer to leave unsaid. “China is a big country,” he pointed out, “and other countries are small countries and that is just a fact.” Indeed it is, and China is big not merely in terms of territory and population, but also military might. Its Communist Party is presiding over the world’s largest military build-up. And that is just a fact, too—one which the rest of the world is having to come to terms with.

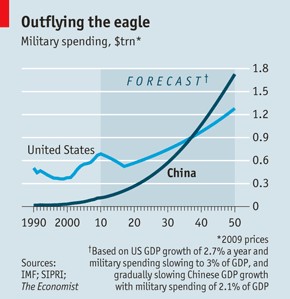

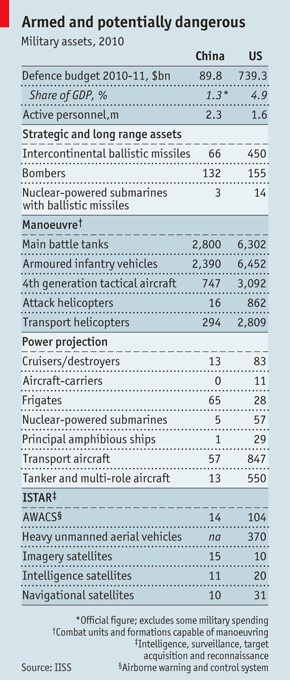

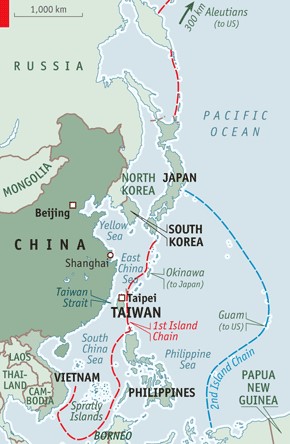

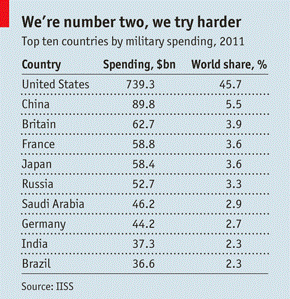

That China is rapidly modernising its armed forces is not in doubt, though there is disagreement about what the true spending figure is. China’s defence budget has almost certainly experienced double digit growth for two decades. According to SIPRI, a research institute, annual defence spending rose from over $30 billion in 2000 to almost $120 billion in 2010.SIPRI usually adds about 50% to the official figure that China gives for its defence spending, because even basic military items such as research and development are kept off budget. Including those items would imply total military spending in 2012, based on the latest announcement from Beijing, will be around $160 billion. America still spends four-and-a-half times as much on defence, but on present trends China’s defence spending could overtake America’s after 2035 (see chart). All that money is changing what the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) can do. Twenty years ago, China’s military might lay primarily in the enormous numbers of people under arms; their main task was to fight an enemy face-to-face or occupy territory. The PLA is still the largest army in the world, with an active force of 2.3m. But China’s real military strength increasingly lies elsewhere. The Pentagon’s planners think China is intent on acquiring what is called in the jargon A2/AD, or “anti-access/area denial” capabilities. The idea is to use pinpoint ground attack and anti-ship missiles, a growing fleet of modern submarines and cyber and anti-satellite weapons to destroy or disable another nation’s military assets from afar. In the western Pacific, that would mean targeting or putting in jeopardy America’s aircraft-carrier groups and its air-force bases in Okinawa, South Korea and even Guam. The aim would be to render American power projection in Asia riskier and more costly, so that America’s allies would no longer be able to rely on it to deter aggression or to combat subtler forms of coercion. It would also enable China to carry out its repeated threat to take over Taiwan if the island were ever to declare formal independence. China’s military build-up is ringing alarm bells in Asia and has already caused a pivot in America’s defence policy. The new “strategic guidance” issued in January by Barack Obama and his defence secretary, Leon Panetta, confirmed what everyone in Washington already knew: that a switch in priorities towards Asia was overdue and under way. The document says that “While the US military will continue to contribute to security globally, we will of necessity rebalance towards the Asia-Pacific region.” America is planning roughly $500 billion of cuts in planned defence spending over the next ten years. But, says the document, “to credibly deter potential adversaries and to prevent them from achieving their objectives, the United States must maintain its ability to project power in areas in which our access and freedom to operate are challenged.” It is pretty obvious what that means. Distracted by campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, America has neglected the most economically dynamic region of the world. In particular, it has responded inadequately to China’s growing military power and political assertiveness. According to senior American diplomats, China has the ambition—and increasingly the power—to become a regional hegemon; it is engaged in a determined effort to lock America out of a region that has been declared a vital security interest by every administration since Teddy Roosevelt’s; and it is pulling countries in South-East Asia into its orbit of influence “by default”. America has to respond. As an early sign of that response, Mr Obama announced in November 2011 that 2,500 US Marines would soon be stationed in Australia. Talks about an increased American military presence in the Philippines began in February this year. The uncertainty principle China worries the rest of the world not only because of the scale of its military build-up, but also because of the lack of information about how it might use its new forces and even who is really in charge of them. The American strategic-guidance document spells out the concern. “The growth of China’s military power”, it says, “must be accompanied by greater clarity of its strategic intentions in order to avoid causing friction in the region.” Officially, China is committed to what it called, in the words of an old slogan, a “peaceful rise”. Its foreign-policy experts stress their commitment to a rules-based multipolar world. They shake their heads in disbelief at suggestions that China sees itself as a “near peer” military competitor with America.

In the South and East China Seas, though, things look different. In the past 18 months, there have been clashes between Chinese vessels and ships from Japan, Vietnam, South Korea and the Philippines over territorial rights in the resource-rich waters. A pugnacious editorial in the state-run Global Timeslast October gave warning: “If these countries don’t want to change their ways with China, they will need to prepare for the sounds of cannons. We need to be ready for that, as it may be the only way for the disputes in the sea to be resolved.” This was not a government pronouncement, but it seems the censors permit plenty of press freedom when it comes to blowing off nationalistic steam. Smooth-talking foreign-ministry officials may cringe with embarrassment at Global Times—China’s equivalent of Fox News—but its views are not so far removed from the gung-ho leadership of the rapidly expanding navy. Moreover, in a statement of doctrine published in 2005, the PLA’s Science of Military Strategydid not mince its words. Although “active defence is the essential feature of China’s military strategy,” it said, if “an enemy offends our national interests it means that the enemy has already fired the first shot,” in which case the PLA’s mission is “to do all we can to dominate the enemy by striking first”. Making things more alarming is a lack of transparency over who really controls the guns and ships. China is unique among great powers in that the PLA is not formally part of the state. It is responsible to the Communist Party, and is run by the party’s Central Military Commission, not the ministry of defence. Although party and government are obviously very close in China, the party is even more opaque, which complicates outsiders’ understanding of where the PLA’s loyalties and priorities lie. A better military-to-military relationship between America and China would cast some light into this dark corner. But the PLA often suspends “mil-mil” relations as a “punishment” whenever tension rises with America over Taiwan. The PLA is also paranoid about what America might gain if the relationship between the two countries’ armed forces went deeper. The upshot of these various uncertainties is that even if outsiders believe that China’s intentions are largely benign—and it is clear that some of them do not—they can hardly make plans based on that assumption alone. As the influential American think-tank, the Centre for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) points out, the intentions of an authoritarian regime can change very quickly. The nature and size of the capabilities that China has built up also count. History boys The build-up has gone in fits and starts. It began in the early 1950s when the Soviet Union was China’s most important ally and arms supplier, but abruptly ceased when Mao Zedong launched his decade-long Cultural Revolution in the mid-1960s. The two countries came close to war over their disputed border and China carried out its first nuclear test. The second phase of modernisation began in the 1980s, under Deng Xiaoping. Deng was seeking to reform the whole country and the army was no exception. But he told the PLA that his priority was the economy; the generals must be patient and live within a budget of less than 1.5% of GDP. A third phase began in the early 1990s. Shaken by the destructive impact of the West’s high-tech weaponry on the Iraqi army, the PLA realised that its huge ground forces were militarily obsolete. PLA scholars at the Academy of Military Science in Beijing began learning all they could from American think-tanks about the so-called “revolution in military affairs” (RMA), a change in strategy and weaponry made possible by exponentially greater computer-processing power. In a meeting with The Economist at the Academy, General Chen Zhou, the main author of the four most recent defence white papers, said: “We studied RMA exhaustively. Our great hero was Andy Marshall in the Pentagon [the powerful head of the Office of Net Assessment who was known as the Pentagon’s futurist-in-chief]. We translated every word he wrote.”

China’s soldiers come in from the cold

In 1993 the general-secretary of the Communist Party, Jiang Zemin, put RMA at the heart of China’s military strategy. Now, the PLA had to turn itself into a force capable of winning what the strategy called “local wars under high-tech conditions”. Campaigns would be short, decisive and limited in geographic scope and political goals. The big investments would henceforth go to the air force, the navy and the Second Artillery Force, which operates China’s nuclear and conventionally armed missiles. Further shifts came in 2002 and 2004. High-tech weapons on their own were not enough; what mattered was the ability to knit everything together on the battlefield through what the Chinese called “informatisation” and what is known in the West as “unified C4ISR”. (The four Cs are command, control, communications, and computers; ISR stands for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; the Pentagon loves its abbreviations).

Just another corner of the network

General Chen describes the period up to 2010 as “laying the foundations of modernised forces”. The next decade should see the roll-out of what is called mechanisation (the deployment of advanced military platforms) and informatisation (bringing them together as a network). The two processes should be completed in terms of equipment, integration and training by 2020. But General Chen reckons China will not achieve full informatisation until well after that. “A major difficulty”, he says, “is that we are still only partially mechanised. We do not always know how to make our investments when technology is both overlapping and leapfrogging.” Whereas the West was able to accomplish its military transformation by taking the two processes in sequence, China is trying to do both together. Still, that has not slowed down big investments which are designed to defeat even technologically advanced foes by making “the best use of our strong points to attack the enemy’s weak points”. In 2010 the CSBA identified the essential military components that China, on current trends, will be able to deploy within ten years. Among them: satellites and reconnaissance drones; thousands of surface-to-surface and anti-ship missiles; more than 60 stealthy conventional submarines and at least six nuclear attack submarines; stealthy manned and unmanned combat aircraft; and space and cyber warfare capabilities. In addition, the navy has to decide whether to make the (extremely expensive) transition to a force dominated by aircraft-carriers, like America. Aircraft-carriers would be an unmistakable declaration of an ambition eventually to project power far from home. Deploying them would also match the expected actions of Japan and India in the near future. China may well have three small carriers within five to ten years, though military analysts think it would take much longer for the Chinese to learn how to use them well. A new gunboat diplomacy This promises to be a formidable array of assets. They are, for the most part, “asymmetric”, that is, designed not to match American military power in the western Pacific directly but rather to exploit its vulnerabilities. So, how might they be used?

Taiwan is the main spur for China’s military modernisation. In 1996 America reacted to Chinese ballistic-missile tests carried out near Taiwanese ports by sending two aircraft-carrier groups into the Taiwan Strait. Since 2002 China’s strategy has been largely built around the possibility of a cross-Strait armed conflict in which China’s forces would not only have to overcome opposition from Taiwan but also to deter, delay or defeat an American attempt to intervene. According to recent reports by CSBA and RAND, another American think-tank, China is well on its way to having the means, by 2020, to deter American aircraft-carriers and aircraft from operating within what is known as the “first island chain”—a perimeter running from the Aleutians in the north to Taiwan, the Philippines and Borneo (see map). In 2005 China passed the Taiwan Anti-Secession Law, which commits it to a military response should Taiwan ever declare independence or even if the government in Beijing thinks all possibility of peaceful unification has been lost. Jia Xiudong of the China Institute of International Studies (the foreign ministry’s main think-tank) says: “The first priority is Taiwan. The mainland is patient, but independence is not the future for Taiwan. China’s military forces should be ready to repel any force of intervention. The US likes to maintain what it calls ‘strategic ambiguity’ over what it would do in the event of a conflict arising from secession. We don’t have any ambiguity. We will use whatever means we have to prevent it happening.” If Taiwan policy has been the immediate focus of China’s military planning, the sheer breadth of capabilities the country is acquiring gives it other options—and temptations. In 2004 Hu Jintao, China’s president, said the PLA should be able to undertake “new historic missions”. Some of these involve UN peacekeeping. In recent years China has been the biggest contributor of peacekeeping troops among the permanent five members of the Security Council. But the responsibility for most of these new missions has fallen on the navy. In addition to its primary job of denying China’s enemies access to sea lanes, it is increasingly being asked to project power in the neighbourhood and farther afield. The navy appears to see itself as the guardian of China’s ever-expanding economic interests. These range from supporting the country’s sovereignty claims (for example, its insistence on seeing most of the South China Sea as an exclusive economic zone) to protecting the huge weight of Chinese shipping, preserving the country’s access to energy and raw materials supplies, and safeguarding the soaring numbers of Chinese citizens who work abroad (about 5m today, but expected to rise to 100m by 2020). The navy’s growing fleet of powerful destroyers, stealthy frigates and guided-missile-carrying catamarans enables it to carry out extended “green water” operations (ie, regional, not just coastal tasks). It is also developing longer-range “blue water” capabilities. In early 2009 the navy began anti-piracy patrols off the Gulf of Aden with three ships. Last year, one of those vessels was sent to the Mediterranean to assist in evacuating 35,000 Chinese workers from Libya—an impressive logistical exercise carried out with the Chinese air force.

Just practising

Power grows out of the barrel of a gun It is hardly surprising that China’s neighbours and the West in general should worry about these developments. The range of forces marshalled against Taiwan plus China’s “A2/AD” potential to push the forces of other countries over the horizon have already eroded the confidence of America’s Asian allies that the guarantor of their security will always be there for them. Mr Obama’s rebalancing towards Asia may go some way towards easing those doubts. America’s allies are also going to have to do more for themselves, including developing their own A2/AD capabilities. But the longer-term trends in defence spending are in China’s favour. China can focus entirely on Asia, whereas America will continue to have global responsibilities. Asian concerns about the dragon will not disappear.

That said, the threat from China should not be exaggerated. There are three limiting factors. First, unlike the former Soviet Union, China has a vital national interest in the stability of the global economic system. Its military leaders constantly stress that the development of what is still only a middle-income country with a lot of very poor people takes precedence over military ambition. The increase in military spending reflects the growth of the economy, rather than an expanding share of national income. For many years China has spentthe same proportion of GDP on defence (a bit over 2%, whereas America spends about 4.7%). The real test of China’s willingness to keep military spending constant will come when China’s headlong economic growth starts to slow further. But on past form, China’s leaders will continue to worry more about internal threats to their control than external ones. Last year spending on internal security outstripped military spending for the first time. With a rapidly ageing population, it is also a good bet that meeting the demand for better health care will become a higher priority than maintaining military spending. Like all the other great powers, China faces a choice of guns or walking sticks. Second, as some pragmatic American policymakers concede, it is not a matter for surprise or shock that a country of China’s importance and history should have a sense of its place in the world and want armed forces which reflect that. Indeed, the West is occasionally contradictory about Chinese power, both fretting about it and asking China to accept greater responsibility for global order. As General Yao Yunzhu of the Academy of Military Science says: “We are criticised if we do more and criticised if we do less. The West should decide what it wants. The international military order is US-led—NATO and Asian bilateral alliances—there is nothing like the WTO for China to get into.” Third, the PLA may not be quite as formidable as it seems on paper. China’s military technology has suffered from the Western arms embargo imposed after the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. It struggles to produce high-performance jet engines, for example. Western defence firms believe that is why they are often on the receiving end of cyber-attacks that appear to come from China. China’s defence industry may be improving but it remains scattered, inefficient and over-dependent on high-tech imports from Russia, which is happy to sell the same stuff to China’s local rivals, India and Vietnam. The PLA also has little recent combat experience. The last time it fought a real enemy was in the war against Vietnam in 1979, when it got a bloody nose. In contrast, a decade of conflict has honed American forces to a new pitch of professionalism. There must be some doubt that the PLA could put into practice the complex joint operations it is being increasingly called upon to perform. General Yao says the gap between American and Chinese forces is “at least 30, maybe 50, years”. “China”, she says, “has no need to be a military peer of the US. But perhaps by the time we do become a peer competitor the leadership of both countries will have the wisdom to deal with the problem.” The global security of the next few decades will depend on her hope being realised. from the print edition | Briefing The dragon’s new teeth Apr 13th 2012, 10:26

After 1949, Mao Ze-Dong - who declared “Democratic Unity” as Time’s one of cover story - put foward PLA’s 3 defensible lines of ocean from “the coast guard” and “near-sea active defense” to “far-seas operations”. The thoughts relied on the conflict between both sides of Taiwan Strait under cold war.

Geopolitically speaking, PLA’s expansion in the world start conflicting apparently with US Army from 1990s after then China’s President Jiang Ze-Min launched the plan to modernize PLA. During 1995’s missile crisis across Taiwan Strait, PLA showed the prominent strategy for provoking the neighbors and signifying the first direct friction with another military power, US. Then, China’s military spending is concentrated by neighbors and US every year until now. More attentively, a glance at hierarchical central military commission (CMC) is another way to see the potential development in the future.

In geographic aspect, there are two main processes of PLA’s development, which includes Taiwan issue and the confrontation with Japan and America. And when it comes to CMC’s membership, the background and the demand results in the level and direction of PLA’s modernization, which processes four steps since 1990 and is scheduled to finish by 2020. Besides, rumor has it that CMC would interfere with the discipline China’s foreign policy. (Yang Jie-Chi and I are friends, but it doesn’t mean the rumor is truth? Ha, I don’t know.)

According to “Chinese civil-military relations in the post-Deng era” in U.S. Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies, Jiang’s membership of CMC, mainly Zhang Wan-Nian, almost experienced Korean War, inclining to hold traditional thoughts and obviously aiming at Taiwan and other interior defense. Jiang’s economical allocation let Jiang have almost of PLA’s loyalty. The good relation among each and every rank lasted through Jiang’s and incumbent Hu Jing-Tao’s tenure. With Hu engrossing the economic progress, PLA spends more than ever, especially air force, and lower risk of Taiwan Strait’s possible war partly because of Taiwan Ma Ying-Jeou’s anti-independent declaration (nothing happens recently). Last April, the remark on the first aircraft’s gain indicated the second step’s finish. That is to say, PLA can achieve “near-sea active defense” which inferred PLA’s ability to expand into the second island chain. No wonder Japan’s former secretary of cabinet Yukio Edano had a short temper to China (uh, including me) last April.

In 2012, Beijing’s fifth-generation leading core will adjust the list of CMC. An analysis, posted by Financial Times’ Kathrin Hille last September, unveiled the next year (2012) CMC’s structure with release of Pentagon. The core of CMC contains about 10 people, listed while talking about the civil-military relationship which Robert Gates worries about very much. In fact, the population of PLA plus PLA’s police is over nearly 3 million but occupy 20.6% newly-elected 42 seats (this time 204 people in total 370 seats) in 17th Central committee of Communist Party.

Another attentive side is the figures, who will get the CMC’s position and practise the duty. Liu Ya-Chou, Wu Sheng-Li, Wang Xi-Hsin may take the control of CMC with Xi Jin-Ping, the next China’s President. Wu Sheng-Li, emphasized by Kathrin’s analysis, has sophisticated experience of sea measuring and mapping in navy life. Wu once tole me his ambition to conquer Taiwan; moreover, Wang Xi-Hsin, who owns No.1 ground force in Asia, has experiences in Sino-Vietnam War and 1989’s Lhasa incident and researches the high-tech application in war field. Both may play a major role in Taiwan affairs.

Taiwan, at a critical Sino-US military crossroad, cannot be conceded in any form and cannot continue its independence from Beijing. Although the peaceful negotiation processes, there is no possibilities of no expiration in Taiwan issue. International media likes reporting Chen Yun-lin and Jiang Bing-quan’s meetings, but this kind isn’t seen as Beijing’s officially final decision. As the recent years’ updated missiles, loaded from 2007 at least 1000, and warship, PLA has the ability to spend less than a week annexing Taiwan in addition to Taipei’s declining defense force.

By the way, Jia Xiudong’s sayings (Yang few takes the opinion) doesn’t flourish as ever; instead, Chinese neighbors’ cooperative military training with US - like East Asia’s South Korea, Japan, and surrounding South China Sea’s nation - will be taken into consideration by China rather than Taiwan affairs. Nowadays, PLA’s oversea activities also contains some international mission in Africa, owing to the close economic tie and gross interest.

The growing fear of Chinese military is filled with a question of “the autocracy faces the democracy” in the world. If China wants to be the real power after America, PLA has to establish the order of principle and scientific evaluation with modernization. History repeats itself - another superpower rises unavoidably.

Recommended 10 Report Permalink 這篇原來的經濟學者文章是Briefing的專題報導,很前瞻性的從歷史回顧、訪問、蒐集資料到分析及圖表解說,以中國的利益及中國軍隊的進化作主觀立場來看中美軍事的平衡,很一流的預測了至少有五年內的西太平洋第一及第二島鏈的局勢。這篇可以說是問起從江澤民時代的「軍務改革」(RMA)後,中國軍隊現代化的中繼站點,當時開始有國際輿論和日本及南海各國的官方及民間社團對於中國海權的疑慮,而時至今日到了筆者要回顧之時,已經近了當年的中共曾經許下的2020年的第三代中國現代化軍隊達成時刻(詳見History Boys乙段)。之後的第四代也已經著手,除了習近平以軍隊組織面及心理層面,對外是航太方面、極地方面及一次多層面全球化作戰能力。 這篇細分,為對於中國軍隊演化的方向如空戰、海戰上的發展優勢與缺點,如反潛作戰、空對空作戰及現代化的海軍(應該是高科技能力)來猜測軍事平衡與否。另一項是軍事預算上的比較作分析。根據BBC去年的報導統計(就是下段這篇2018年2月13日的文章),中國政府在國防預算在2007年至16年之間增長了近120%。 有關的中國軍隊國際化,筆者有看過一篇BBC的報導The globalisation of Chinas military power, Jonathan Marcus(https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-43036302)其中兩段: Chinas progress and technical abilities are remarkable - from ultra-long-range conventional ballistic missiles to fifth generation fighter jets. Last year the first hull of Chinas latest warship - the Type 55 cruiser - was put into the water. Its capabilities would give any Nato navy pause for thought. China is working on its second aircraft carrier. It is revamping its military command structure to give genuine joint headquarters involving all the key services. In terms of artillery, air defence and land attack it has weapons that out-range anything the US can deploy. 想起來當天花了要一個禮拜理解中國的常備兵有230萬左右,加武警及民兵就接近500萬的地球最大規模組織,和目前2018年仍然是世界最大預算的美國山姆叔叔隊,已經是老數據了。當時還看了看殲已經到了要20代了,還要看東風幾代了,對了筆者正在寫的這裡不知是不是極右藍營(好煩,除了聯合報沒有什麼可以寫的部落格了)有的講侯佩岑之後還有邱沁宜還是謝祖武(幽默一下應付udn的某些知名部落客),筆者記得日本有要採購法國的F-2之後的F-4,韓國想買美國洛克希德的F-22到沒幾年後有F-32甚至首批有匿縱功能的F-35,這就說到台北的小英總統也想買的就是F-35,看她去年稅收新台幣一億都可以買個三十幾架來玩了,但她先買戰車汰換。現在看來中國的空軍不弱但聽說出事率還沒下降,而海軍雖然有一艘航空母艦但是仍不足以有規模的戰隊形成,所以和日本、美國相比還有些問題,不能硬碰硬。 當要由中共第五代領導接班時,胡錦濤所中意的將領現在大部份屆齡退休,要不就是捲入貪污疑雲,真不知哪時誰還認得筆者。筆者在回文中提到的有主導這波現代化部隊的劉亞洲、王西欣、章沁生、吳勝利的軍事思想(另外筆者其他篇有提過前國防部長梁光烈和常萬全),亦可見於楊中美博士,時報出版,歷史與現場198-中國即將發生政變,解析政變前夜的九大關鍵人物,書中也有他們顯赫的事蹟及作戰經驗描術,比如王西欣受胡錦濤重用的有中越戰爭及1987-89平定拉薩藏民暴動等。 有關東海和南海海權的爭議,在這年的4月22日,及八、九月時因更嚴峻的局勢,即台灣有保釣人士使野田佳彥被媒體於首相官邸門口圍住來問的那附近時間,之時的問題曾經稍微加劇過,而經濟學者雜誌在那兩三個月有較密集而多種角度的探討。筆者在進行對那兩、三個月文章的回顧這兩海域方面,會繼續寫出筆者的立場。另外亦可先進入筆者回覆經濟學者的報導的My comment: https://www.economist.com/user/2791934/comments 「My nationalism, and don’t you forget it, Jul 30th 2016, 11:03」有當海牙的國際法院的仲裁法庭宣判由菲律賓提案的南海海權問題的筆者個人見解。 (未完成) *筆者同時參考前一週的經濟學者雜誌leader欄評論 Asias balance of powerChina’s military riseThere are ways to reduce the threat to stability that an emerging superpower posesApr 7th 2012 | from the print edition

NO MATTER how often China has emphasised the idea of a peaceful rise, the pace and nature of its military modernisation inevitably cause alarm. As America and the big European powers reduce their defence spending, China looks likely to maintain the past decade’s increases of about 12% a year. Even though its defence budget is less than a quarter the size of America’s today, China’s generals are ambitious. The country is on course to become the world’s largest military spender in just 20 years or so (see article). Much of its effort is aimed at deterring America from intervening in a future crisis over Taiwan. China is investing heavily in “asymmetric capabilities” designed to blunt America’s once-overwhelming capacity to project power in the region. This “anti-access/area denial” approach includes thousands of accurate land-based ballistic and cruise missiles, modern jets with anti-ship missiles, a fleet of submarines (both conventionally and nuclear-powered), long-range radars and surveillance satellites, and cyber and space weapons intended to “blind” American forces. Most talked about is a new ballistic missile said to be able to put a manoeuvrable warhead onto the deck of an aircraft-carrier 2,700km (1,700 miles) out at sea. In this section · »China’s military rise Related topics · Taiwan · Asia · China China says all this is defensive, but its tactical doctrines emphasise striking first if it must. Accordingly, China aims to be able to launch disabling attacks on American bases in the western Pacific and push America’s carrier groups beyond what it calls the “first island chain”, sealing off the Yellow Sea, South China Sea and East China Sea inside an arc running from the Aleutians in the north to Borneo in the south. Were Taiwan to attempt formal secession from the mainland, China could launch a series of pre-emptive strikes to delay American intervention and raise its cost prohibitively. This has already had an effect on China’s neighbours, who fear that it will draw them into its sphere of influence. Japan, South Korea, India and even Australia are quietly spending more on defence, especially on their navies. Barack Obama’s new “pivot” towards Asia includes a clear signal that America will still guarantee its allies’ security. This week a contingent of 200 US marines arrived in Darwin, while India took formal charge of a nuclear submarine, leased from Russia. En garde The prospect of an Asian arms race is genuinely frightening, but prudent concern about China’s build-up must not lapse into hysteria. For the moment at least, China is far less formidable than hawks on both sides claim. Its armed forces have had no real combat experience for more than 30 years, whereas America’s have been fighting, and learning, constantly. The capacity of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) for complex joint operations in a hostile environment is untested. China’s formidable missile and submarine forces would pose a threat to American carrier groups near its coast, but not farther out to sea for some time at least. Blue-water operations for China’s navy are limited to anti-piracy patrolling in the Indian Ocean and the rescue of Chinese workers from war-torn Libya. Two or three small aircraft-carriers may soon be deployed, but learning to use them will take many years. Nobody knows if the “carrier-killer” missile can be made to work.

As for China’s longer-term intentions, the West should acknowledge that it is hardly unnatural for a rising power to aspire to have armed forces that reflect its growing economic clout. China consistently devotes a bit over 2% of GDP to defence—about the same as Britain and France and half of what America spends. That share may fall if Chinese growth slows or the government faces demands for more social spending. China might well use force to stop Taiwan from formally seceding. Yet, apart from claims over the virtually uninhabited Spratly and Paracel Islands, China is not expansionist: it already has its empire. Its policy of non-interference in the affairs of other states constrains what it can do itself. The trouble is that China’s intentions are so unpredictable. On the one hand China is increasingly willing to engage with global institutions. Unlike the old Soviet Union, it has a stake in the liberal world economic order, and no interest in exporting a competing ideology. The Communist Party’s legitimacy depends on being able to honour its promise of prosperity. A cold war with the West would undermine that. On the other hand, China engages with the rest of the world on its own terms, suspicious of institutions it believes are run to serve Western interests. And its assertiveness, particularly in maritime territorial disputes, has grown with its might. The dangers of military miscalculation are too high for comfort. How to avoid accidents It is in China’s interests to build confidence with its neighbours, reduce mutual strategic distrust with America and demonstrate its willingness to abide by global norms. A good start would be to submit territorial disputes over islands in the East and South China Seas to international arbitration. Another step would be to strengthen promising regional bodies such as the East Asian Summit and ASEAN Plus Three. Above all, Chinese generals should talk far more with American ones. At present, despite much Pentagon prompting, contacts between the two armed forces are limited, tightly controlled by the PLA and ritually frozen by politicians whenever they want to “punish” America—usually because of a tiff over Taiwan. America’s response should mix military strength with diplomatic subtlety. It must retain the ability to project force in Asia: to do otherwise would feed Chinese hawks’ belief that America is a declining power which can be shouldered aside. But it can do more to counter China’s paranoia. To his credit, Mr Obama has sought to lower tensions over Taiwan and made it clear that he does not want to contain China (far less encircle it as Chinese nationalists fear). America must resist the temptation to make every security issue a test of China’s good faith. There are bound to be disagreements between the superpowers; and if China cannot pursue its own interests within the liberal world order, it will become more awkward and potentially belligerent. That is when things could get nasty. from the print edition | Leaders *附一篇過幾天後的相關雜誌編輯評論 Arms sales to TaiwanFighter-fleet responseMay 1st 2012, 13:18 by J.R. | TAIPEI

JUST as everything was becoming as clear as mud, America has unexpectedly raised the possibility that it might sell Taiwan the F-16 C/D fighter jets that it has been requesting since 2006. The move would infuriate China. Officials in Beijing have in the past voiced strenuous opposition to the sale of F-16 C/Ds, marking it as a line in the sand, of the kind that can’t be crossed. As it stands, the gesture was remarkably blunt. Days before the arrival of Hillary Clinton, America’s secretary of state, and smack dab in the middle of confusions to do with the custody of Chen Guangcheng, the boffins in charge of America’s foreign affairs have made things much tougher than they might have done, had they tarried for some weeks or months. It was on Friday that the White House said, seemingly out of the blue, that it is “mindful of...Taiwan’s growing shortfall in fighter aircraft” and “committed to assisting Taiwan in addressing the disparity in numbers of aircraft through our work with Taiwan’s defence ministry.” Saying this would be a “high priority” for its new assistant secretary of defence, the administration has set out to decide on a near-term course of action for addressing Taiwan’s so-called fighter gap, “including through the sale to Taiwan of an undetermined number of new U.S.-made fighter aircraft.” These comments represent a departure from the American government’s previous declarations. The line had been that upgrades to Taiwan’s existing F-16 A/B jets, part of a $5.85 billion weaponry package from last year, would suffice to meet Taiwan’s defence needs. Even on Friday the White House did not specify which the kind of fighter aircraft it might entertain selling. In the recent past Taiwan has expressed interest in purchasing the even-newer F-35 fighters, for their vertical-landing capability (helpful if China’s missiles take out Taiwan’s runways). But military experts in Taiwan say given the current conditions of America’s weapons market, the White House could only be referring to F-16 C/Ds. No one in Taiwan doubts that the island needs new jets. China has 2,300 military aircraft in service, to Taiwan’s 490. Of those 490, around 60 are elderly F-5 jets that were sold to Taiwan during the Reagan administration. Another 50-odd are French-made Mirage fighters which are scheduled for retirement over the next several years; their maintenance and spare parts have become too expensive. The U.S.-Taiwan Business Council, a lobby group which represents American defence companies, among others, estimates that Taiwan will have as few as 75 usable modern fighters at its disposal from 2016 to 2022, while the F-16 A/B planes are undergoing upgrades. Taiwan’s defence ministry has welcomed these remarks, as well they might. The question is: why is America raising this issue now? Arthur Ding, a military expert at Taiwan’s National Chengchi University, suspects that it’s mere lip service on the part of some pushy members of Congress, and pre-election posturing on the part of the Obama administration. “I don’t think this will result in a sale,” Mr Ding said. The announcement was made in a letter from Robert Nabors, the White House’s director for legislative affairs, to a Republican senator, John Cornyn. Mr Cornyn has been pushing for the F-16 C/D sale and at the same time blocking the confirmation of the administration’s appointment of Mark Lippert as assistant secretary of defence for Asian and Pacific security affairs, the top Pentagon official for Asia, since October. In response to the letter, Mr Cornyn has removed his resistance to Mr Lippert’s appointment. Other analysts however, such as Alexander Huang of Tamkang University in Taipei, are optimistic that the American government and Congressional supporters of the F-16 C/D sale are close to reaching a compromise. He thinks a sale could be near at hand. Other backers of the F-16 C/D plan think it’s a good time for Taiwan’s government to submit a formal request to the Americans. “I think the statement in the letter is a genuine one,” says Mr Huang. Whichever the case, the Taiwan-based analysts agree, in the broader picture America probably timed the announcement to coincide with the political turbulence surrounding the downfall of Bo Xilai. A distracted China is probably less likely to make a fuss.

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |