字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/07 21:37:37瀏覽15|回應0|推薦0 | |

Governing ChinaThe Guangdong modelOne Chinese province adopts a beguilingly open approach—up to a pointNov 26th 2011 | FOSHAN AND GUANGZHOU | from the print edition

UNLIKE attention-seeking politicians elsewhere, senior Communist cadres in China like to keep their ambitions hidden. If anything, they signal grey conservatism, stressing how little they wish to change things. But as the country awaits a change of its leadership late next year, some high officials are up for a bit of self-promotion. In Guangdong province in the south the Communist Party chief, Wang Yang, is dropping hints that his more liberal style of governing might offer a better way for running the country. Guangdong has long been the most vibrant and economically liberal province in China. Now the idea that economic liberalism might be matched by greater political openness has come to be called the “Guangdong model”. A prominent supporter is Xiao Bin of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, the provincial capital. On the blackboard, he draws a picture of an egg. He makes chalk marks on the white to show how changes can be made in the way the party rules, while leaving the yolk—for which read a Communist Party monopoly on power—unmarked. In this section

Mr Wang, who is 56, has been a member of the ruling Politburo since 2007. He knows well how to keep within the party’s bounds. He rarely talks of the Guangdong model, which would sound like a slap at others. But among academics and online commentators, the term has blossomed. Guangdong newspapers occasionally talk about it.

Fans of the model fiercely defend it against advocates of its rival promoted by the party chief of Chongqing deep inland, Bo Xilai, who has a flair for publicity. Both Mr Wang and Mr Bo may join the Politburo’s standing committee next year, when seven of nine members, including President Hu Jintao and the prime minister, Wen Jiabao, will step down. Mr Bo trumpets the importance of state-owned enterprises, traditional socialist values and the inspirational power of Mao-era songs—while getting tough on organised crime. Maoist websites lionise Mr Bo; the Chongqing model is held up in shining contrast to that of Guangdong and its “capitalist roaders”. Six decades of Communist rule have been punctuated by battles between the left (as Mr Bo’s supporters are proud to call themselves) and the right (a label that carries a stigma to this day). This battle is exceptional, however. It is being fought out not in arcane commentaries in party newspapers but in open debate. Both camps hold symposiums about their respective models. A book is out about the Chongqing model. In literary terms, Mr Xiao admits that the Guangdong camp is lagging somewhat. Perhaps the debate generates more heat in public than it does in the Communist Party itself. A researcher at Guangdong’s party school says Guangdong and Chongqing are not in opposition. Both regions, he says, are learning from each other. For example, Chongqing is building the development zones to attract investors that Guangdong pioneered in the 1980s. Guangdong, he says, could learn from Chongqing’s efforts to absorb migrants from the countryside into city life. Guangdong academics have studied Chongqing’s experiments in creating markets for rural land, where powerful restrictions apply even in “liberal” Guangdong. In the political realm, however, Mr Wang’s supporters point to changes which, they say, are distinctive. One concerns the role of trade unions, a rather sensitive area for a party that is still unnerved by the role that Solidarity played in Poland in the 1980s to bring down Communist power. Mr Wang’s rethink was triggered by a spate of 200-odd strikes last year in the Pearl River delta that began in May with workers downing tools at a Honda car-parts factory in Foshan, near Guangzhou. Mr Wang, says an academic, chose not to see the strikes as a threat to political stability. Indeed he expressed sympathy with the workers’ demands (which is perhaps easier to do at companies owned by foreigners). Elsewhere in China ringleaders are commonly rounded up once strikes have been settled, but those in Guangdong were not. All the incidents, the academic says, had “happy endings”, with pay increases of 30-40%. Buying off strikers is common enough in China. But Mr Wang went further, encouraging state-affiliated trade unions (there are no independent ones) to be more active in representing workers’ interests. Trade unions in China are normally little more than creatures of management, run by party cadres. Prodded by Mr Wang, Guangdong’s unions began encouraging collective bargaining, a practice officially authorised but widely disliked by local officials who fear worker activism and upward wage pressures. Mr Wang’s views did not strike an instant chord with his subordinates. Most participants at one meeting on how to handle the strikes “didn’t get it” when he called for a hands-off approach, says someone with knowledge of the proceedings. By contrast, during a large-scale taxi strike in Chongqing in 2008, Mr Bo was more interventionist. He held an unusual televised meeting with drivers, but later launched a sweeping anti-mafia campaign that resulted in a wealthy businessman accused of organising the strike being sentenced to 20 years in prison for gangsterism and disrupting transport. Supporters of the Guangdong model also point to the greater leeway Mr Wang has given NGOs, which are heavily circumscribed in China. Their registration in Guangdong, and especially in Shenzhen, a trailblazing economic zone bordering Hong Kong, involves fewer hoops. Mr Wang has been credited with promoting more open access to information about government spending. In 2009 Guangzhou became the first Chinese city to publish all its budgets. It is never entirely clear how much of these initiatives have been taken by Mr Wang himself. Guangdong in general and Shenzhen in particular have long enjoyed unusual freedom to experiment. This year Mr Wang has been promoting the goal of a “happy Guangdong” (the pursuit of which is enshrined in the province’s new five-year plan). Public happiness, assessed by opinion polls, is being introduced as a new criterion for judging local leaders’ suitability for promotion. Yet unhappiness remains rife, and in this Guangdong is no exception. Dissatisfaction is widespread among the more than 36m migrants in Guangdong, one-third of the provincial population, many of whom work in harsh conditions. Protests, sometimes violent, are common. In Dadun village, on the edge of one of Guangzhou’s satellite towns, a notice outside the government headquarters promises rewards of up to 10,000 yuan ($1,600) for turning in “criminals” involved in large riots in June triggered by security guards roughing up a street hawker. The rioters were migrants who work in countless small jeans factories, one even in a temple courtyard, trimming threads and stamping on studs. Nor does the Guangdong model extend to free and fair elections. In September Dadun held a ballot for seats in the local legislature. But only its fewer than 7,000 Cantonese inhabitants were allowed to vote, and not the 60,000-odd sweatshop labourers from other provinces. In a village near Foshan, residents elected an independent candidate, ie one who did not have party backing. Plainclothes goons now keep watch on his home. A villager confides her support for the new legislator only in a hushed tone. Mr Wang’s egg-yolk remains inviolate. from the print edition | Asia

The Guangdong model Nov 28th 2011, 08:29

Thanks for this profound essay, the author of which optimistically tells readers that the strong China must receive the element of capitalism letting Beijing and local inhabitant encourage with each other while this biggest communist state walks toward the more democratic side. In this way, Guangdong is a typical demonstration when it comes to the story of the recent 30-year China’s modernization. Besides, Wang Yang, the outstanding Chinese officer at the age of 40-60, has been extending his experienced career and open mind from Chongqing to Guangdong in 2007, the party secretary of where is seen as the doorway without obstacle to “make fish jump into the dragon’s lake”. It was this seat that the respectful Zhao Zi-Yang’s first eligible work for China’s Communist Party (CCP) after new China’s establishment in 1949.

Like Hsieh Chung-Ting(Frank Hsieh)’s political position in Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party, Wang Yang now gets the second largest grade in the pedigree of China’s Communist Youth League(CCYL) among the fifth generation of CCP. Under the stable and interesting two-faction system in the near future, Wang, also once thought of as the potential candidate of 2012-2017’s prime minister, faces the counterpart in princeling party, Bo Xi-Lai. Wang’s characteristic as well as Guangdong’s geographic site near Hong Kong are really a match, creating the Guangdong model.

In comparison, being the secretary of Chongqing and having a straight temperament (as I know his marriage and the famous knock in Dalian), Bo takes the active measure to advance the city’s society from the time when Wang handed over Chongqing to Bo to the present. There is few saying Guangdong’s model but talking too much about so-called Chongqing experience. Different ways to exercise policy make different political culture and other’s feelings. On the one hand, Bo’s arguable policy always annoy China’s incumbent president Hu Jing-Tao, who anyway sees and forces many Chinese to see Bo as nobody. On the other hand, Wang gains more and more support from Chinese bloggers, social network’s users, businessmen, academy and Beijing’s central officer including Li Ke-Qiang and Wang Gang(who once famously praised by Newsweek).

In Wang’s youth, Deng Xiao-Ping admires Wang’s strive when he was just a local town’s officer on low position. One of Deng’s “South Supervision” was to see the construction made by Wang. After practice in central Beijing for several years, he joined in the “Western Development” becoming Chongqing’s party secretary. In 2007’s summer, Guangdong was at the critical point of economical transformation; meanwhile, many researchers in China Study perdicted that Guangdong’s GDP would surpass Taiwan island’s by 2012 and it was mandatory for Beijing to strengthen Guangdong’s rapidly progressive economy. Guangdong’s advance in China’s economy was also emphasized in The Economist’s “the leader column” for several times in 2007’s summer. Unanimously, Wang’s style and fame in Chongqing let Wang be announced to lead Guangdong by the fourth generation of CCP in December, 2007. Owning the beautiful Guangdong’s city hall and office in Guangzhou, Wang invited Ma Yuan, the Alibaba Group chairman, to help improve Guangdong’s development of e-commerce, social network and cooperation of business-government. Besides, Wang solved the various problem of closing enterprise. Wang not only donates concentration on the welfare of massive people but also shows his ambition to promote himself to a powerful position in CCP through his splendid political grade. Due to the success of “New Ten Construction”, Guangdong’s GDP surpassed Taiwan’s in the spring of 2011. This advantage for Beijing can be used to conquer Taiwan. By the way, Guangdong’s economy is often a reference to the newly-devoloping country like Vietnam. Although there are sometimes workers or farmers conflicting with government, Guangdong is still the suitable surroundings of industrial investment.

“If love is still alive or dream can happen, even very few possible, just have my heart wholly love you forever. I cannot explain more and better how I love you but to resemble unstoppable winds and needling rain reflecting on my endless love.” Hong Kong’s "If God says the love" by Liu De-Hua(Andy Lau) maybe give a better description to say Wang Yang, who has already become a star of the fifth CCP. With Wang’s “Happy Guangdong”, Wang, not offending anyone or any principle in CCP, exercises the democratic way better than Bo’s logic. Moreover, Wang can sit realizing his goal to be the top 9 CCP’s central committee with Li Ke-Qiang, who owns Anhui’s origin and CCYL the same as him.

Recommended 43 Report Permalink 這篇是筆者第一年在經濟學人雜誌少數有成功推銷中共黨政經驗成功的例子-汪洋的重慶及廣東地方與跨域治理經驗,即在當年公認上除了薄熙來的重慶經驗,就屬今天即將就任政協主席的汪洋所開發的廣東模式啦。汪的模式至今公任為各地方官爭相模倣的對象,平實而穩健,不急燥親民也在行政上有些和政治分隔開,其措施上較親市場導向而受馬列思想影響較少,沒有薄某當年的成天造勢大會來的喧鬧。算起來當年太子黨和團派各有千秋,今天汪兄者勝出,且深化市場民主。當年筆者時任副總理李克強先生的提醒,經濟政策上注意到汪洋從重慶「治政」乃至廣東省的「全力開放」演變,敢大刀闊斧切齊市場者當年還不多。汪在民主政治上也有在深圳試行似西方代議「市議會」的「一年諮詢局」,因此當年引起烏崁村覺得「可以起事」,算一題小問號語句。 在此省略了一張展場模特兒照片,這是汽車會場一景,有個模特兒悠閒地躺著,似說明當天廣東省的安閒,工業上的先進使駕駛可無虞地駕輕就熟全省的旅遊景點,吃喝玩樂任君挑選。然後第二張稍比較今昔廣東重慶,及隱喻和薄附近的明爭暗鬥。這經濟學人雜誌算來,和英國金融時報、美國時代雜誌及華盛頓郵報等之前較多中共黨政的要聞來說,這方面的蒐集資料及心得變得十分用心,也比較客觀及經濟理性中道。當時台北和陳水扁前總統兄弟檔政治人物謝長廷出訪福建尋根及密會,就是汪洋的牽線安排。筆者文中提到美國新聞週刊亦曾以同類筆法稱讚過前科技部部長王剛,即是一例。筆者從鄧小平南巡垂青「娃娃市長」及至後來參與胡錦濤「開發大西部」重慶現代化模式的雛形,以及今天習近平主席很懷念的廣東省的「新十大運動」,在2008年還曾請馬雲一同開發電子化政府的全國首次試行,實現流線型政府及確立類似厲革計畫REGO的模式在全國逐步展開,堪為模範,就這麼讓汪當了政協主席。 「If God Say Love.」是筆者小時候在舊喬登美語新莊分校,今天凱琳美語升學補習班讀書時,輔大英語的工讀老師翻譯劉德華1996年出品的「如果天有情」的話,有感情的存在是要上帝說了算,非完全人力所能干涉的了的事,涉及世俗層面既多且雜,每人均只出一己之棉帛實在太淺。「就讓我和你沉睡在夢裡,可知我的心不願意醒:如果天有情,如果夢會理,就像風吹不息雨打不停,此情不渝。」如果這裡有愛,廣東的總體經濟在2007年超越了台灣,成為中國在亞洲經濟的新興指標,跳脫了舊NIEs新興經濟工業體的發展模式及亞洲四小龍思維,珠三角經濟地帶-深圳、珠海及廣州結合發展較早的東莞是BRICs中閃耀的明珠。很高興能搭上這波潮流,在數年後這個粵語文化圈從山寨一躍成為科技一流研發基地,不少像雙系統、小平板及智能機器人與3D產品都由此而來。今日深圳東莞的發展仍在綜合評估前十名,雖然有了北京超越上海人均所得的新局勢,廣東的新銳輩出,新觀念也會帶動人民的新生活及政治思想。 以下是數週後的兩篇在Leader和Asia欄相關報導中國的經濟(第一篇)和政治面(第二篇)和WTO的關係,評論中國政府對WTO的規定所帶來的自我突破及意識型態矛頓點反思,尤其是當年中國還是胡錦濤先生,美國是希拉蕊柯林頓的中美領導間之貌合神離問題:(2018,08,04補充) China’s economy and the WTO All change In two articles, we examine how China has been altered by its entry into the WTO ten years ago. First, the economy. Second, the political impact Dec 10th 2011 | HONG KONG | from the print edition

THE World Trade Organisation (WTO), like many clubs, denies patrons the right of automatic readmission. Having quit the organisation’s predecessor shortly after the Communist revolution of 1949, China had to wait 15 long years to gain entry after reapplying in the 1980s. The doors finally opened on December 11th 2001, ten years ago this week. The price of re-entry was as steep as the wait was long. China had to relax over 7,000 tariffs, quotas and other trade barriers. Some feared that foreign competition would uproot farmers and upend rusty state-owned enterprises (SOEs), as to some extent it did. But China, overall, has enjoyed one of the best decades in global economic history. Its dollar GDP has quadrupled, its exports almost quintupled. In this section

Related topics

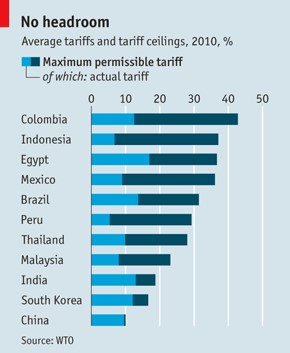

Many foreigners also prospered. American foreign direct investment reaps returns of 13.5% in China, compared with 9.7% worldwide, according to K.C. Fung of the University of California, Santa Cruz. China imposes lower tariffs on average than Brazil or India. The gap between what it can charge, under WTO rules, and what it does charge is also unusually small. So unlike its peers, China could not raise tariffs much even if it wanted to (see chart). Yet in America, China’s single biggest trading partner, sentiment towards the country has turned starkly negative. In a recent poll, 61% of Americans said that China’s recent economic expansion had been bad for America; just 15% thought it had been good. This partly reflects China’s controversial currency regime. By keeping the exchange rate down, China’s critics allege, it has gained a substitute for the mercantilist measures it gave up to join the WTO. Foreign frustration is partly a sign of China’s success. As its economy has grown and matured, the stakes have risen. Foreign firms lament losing trade battles they might not bother to wage in a less lucrative market. They also face competition from local upstarts in markets where no such rivals previously existed. Electronic payments are one example. China’s first ever payment card was issued in 1986 by MasterCard. Foreign brands remained dominant at the time of China’s WTO entry. But shortly afterwards, China’s central bank established a domestic competitor, China UnionPay, and gave it a de facto monopoly over the handling of local-currency payments between merchants and banks. This setback might have been easier to take for foreign companies had the market not since grown tenfold, to $1.6 trillion, according to The Nilson Report, an industry newsletter. China’s economy has evolved faster than anyone hoped. But its economic philosophy has not. Long Yongtu, who helped China win admission to the WTO, recently said that China is now moving further away from the organisation’s principles. To modernise its economy, it has remained wedded to industrial policies, state-owned enterprises, and a “techno-nationalism” that protects and promotes home-grown technologies. Many foreign companies feel they must compete not with Chinese firms but with the Chinese state. Between them, China’s central and local governments own over 100,000 companies and implicitly favour many more. Thanks to the WTO, foreign firms are no longer required to hand over technology in exchange for entry to China’s market. But many still feel an informal pressure to do so. China is also keen to promote its own firms by enforcing its own technological standards, such as for 3G mobile phones. Many of these interventions violate the spirit, if not always the letter of WTO rules. In response, America often pushes back bilaterally rather than in Geneva, according to a former American trade negotiator. This is partly because companies worry they will face retribution from China’s government if they provide evidence against it in a trade case. It is also because much of what China does falls into a grey area that is not easy for the WTO to police. China, on the other hand, is growing more comfortable with the WTO machinery. In its early years as a member, it shied away from confrontation, points out Henry Gao of Singapore Management University. In 2006, for example, America threatened to file a complaint over China’s duties on kraft linerboard. China lifted the duties the next working day. But now the Chinese have learned the ropes, they have also become more proactive. “Now they defend themselves,” says Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute, a Washington think-tank. “They initiate cases. And when they lose, they comply.” In some cases the discrimination is no worse than before, it is simply more visible. As part of its WTO agreement, China now circulates draft laws and regulations for 30 days to collect comments. That has made it easier for foreigners to spot foul play. America recently complained that China had failed to notify the WTO of nearly 200 subsidy programmes, such as those supporting green-energy technology. It knew this in part because China, following its newly transparent practice, had disclosed many such programmes online, the former negotiator said: “Similar policy announcements were neibu (for limited distribution) in the past.” China’s trade policies may look a little uglier than WTO members had hoped when they opened the club’s doors ten years ago. But that is partly because the lights have been turned on. Read on: Chinese politics and the WTO from the print edition | Asia

Chinese politics and the WTO No change Hopes of sparking political change have come to nothing so far Dec 10th 2011 | BEIJING | from the print edition

WHEN trying to persuade Congress in 2000 that China should be let into the World Trade Organisation (WTO), America’s then president, Bill Clinton, knew how to win over the sceptics. China’s admission, he said, was likely to have “a profound impact on human rights and political liberty”. A decade on, China’s disappointed liberals no longer suggest that freer trade will speed political reform. China’s media have been trumpeting the tenth anniversary on December 11th of the country’s WTO accession. In China as much as in America, the event was seen as of far greater importance than a mere pledge by China to reduce barriers to its markets (moves towards which had long been under way). For both countries it was a crucial part of restoring calm to a relationship that had been marred by annual fights in Congress over whether to keep granting China most-favoured-nation trading status (as enjoyed by most of America’s other trading partners). Mr Clinton’s remarks preceded bitterly contested votes in Congress in 2000 that ended the annual renewal process and ensured America would share any benefits from the market-opening measures pledged by China on entering the WTO. In this section

Related topics Chinese officials did not share Mr Clinton’s belief in what he called the “quite extraordinary” change that the WTO would bring about in China, politically as well as economically. Such views were bolstered in the West by supportive comments from some Chinese dissidents. (“Before, the sky was black; now it is light. This can be a new beginning,” Mr Clinton quoted one of them, Ren Wanding, as saying.) But even the man seen by many in the West as China’s arch (economic) reformer, the then prime minister Zhu Rongji, had no truck with such views. A recent four-volume set of Mr Zhu’s speeches, including many not previously published, shows him to have shared hardliners’ concerns about perceived Western efforts to undermine Communist Party rule in China. “Western hostile forces are continuing to promote their strategy of Westernising and breaking up our country,” he told provincial officials in one now-declassified speech, four months after China had joined the WTO. He accused such people of conducting “infiltration and sabotage” in an effort to foment instability, pointing to large-scale protests early in 2002 by workers in state-owned enterprises (independent observers detected little if any sign of foreign involvement). Mr Zhu’s reformist zeal in the economic realm helped to foster the impression of a country willing to take considerable political risks in order to create a more market-driven economy. The then party chief, Jiang Zemin, was also pushing through a controversial revision to the party’s constitution to allow owners of private businesses to become members. But high hopes among some Chinese liberals faded as the decade wore on. Cao Siyuan, who heads an independent think-tank in Beijing, says he and like-minded intellectuals were “over-optimistic” about the ability of the WTO to promote further change, such as the development of a robust and independent legal system. The last decade has seen huge social changes, but these have been a legacy mainly of pre-WTO membership reforms, such as the privatisation of housing and the loosening of controls on internal migration. And with the Communist Party again facing a big leadership shuffle next year, few believe that long-neglected political reforms will be revived any time soon. Mr Cao has recently published a call for a “division of powers” within the party as a step towards making China more democratic. He claims many in the party support such a notion, but do not dare say so openly. Mr Cao says police stopped him from leaving his home during the visit to Beijing in August by America’s vice-president, Joseph Biden. In his speech in 2000, Mr Clinton said that WTO membership would accelerate the shrinkage of the state-owned sector which had been “a big source of the Communist Party’s power”. This, he said, would lead to “profound change”. Many liberals complain, however, that remaining state firms not only still control the commanding heights of the economy but are in some cases stepping up their resistance to encroachment by the private sector. In recent years officials have increased their efforts to ensure that party cells are set up in private firms. Several local governments have started requiring private companies to contribute about 0.5% of their payrolls to sponsor party activities on their premises. Such was the seeming status symbol of WTO membership a decade ago that few in China openly criticised the decision. A Beijing academic, Han Deqiang, was a rare exception. His book, “Collision: the Globalisation Trap and China’s Real Choice”, gave warning of an American plot to use the WTO to “Westernise” China. He remains a fierce critic. Karl Marx, he says, would have agreed with the view that economic liberalisation leads to political change. “It’s a matter of time,” he says. Perhaps Mr Clinton can draw comfort. from the print edition | Asia |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |