字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|||

| 2019/10/14 00:07:28瀏覽389|回應0|推薦0 | |||

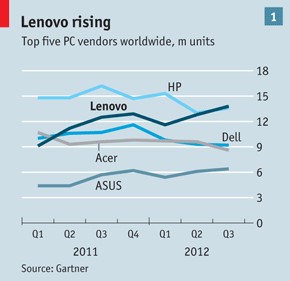

※My Strabucks Name Jan 9, From guard shack to global giant Jan 16, A private life Jan 21 這三篇的回顧可以連起來讀。 這篇是2013年初,經濟學者雜誌對於聯想集團,基於在B2C市場主要致力於筆記型電腦,在B2B市場主要是作終端伺服器的主要銷路,所寫的回顧及樂觀評估。 曾經滄海難為田,何以為聯想能夠成為一流生產個人電腦的跨國企業呢?聯想是現今僅次於惠普hp的第二大個人電腦生產商,在年度銷售營業額,兩間纏鬥八年多之久,撇開了台灣的雙雄宏碁和華碩和美國的戴爾電腦DELL。第一季財報在六月底公佈時,全球市佔24.9%,又回到了第一名位置。又在2014年10月底起逐步從Google手中收購Motorola,一度是前三大全球手機供應商。其實併購和出資一直是聯想十年來在個人電腦業務上,穩健求營運進步的手法:2011年和NEC合併電腦製作業務,德國Medion,和2018年合併Fujitsu電腦製造部門,都是很顯著的例子。 聯想在1984年出生,由中國科學院計算技術研究所創辦,在1989年更名為「北京聯想計算機集團公司」至今。最初英文名字是叫Legend,2002年改名字叫作Lenovo。2005年聯想收購了IBM的電腦業務部門,微軟的Encarta百科全書是這麼記載當時的情形 「In 2004 IBM decided to get out of the PC business, which had become only occasionally and marginally profitable. IBM sold the majority share of its PC division to Lenovo Group Ltd., China’s largest manufacturer of PCs, retaining only an 18.9 percent minority share. The sale, which amounted to $1.75 billion in cash, stock, and acquisition of debt, meant that Lenovo became the third largest PC maker in the world, after Dell Computer Corporation and Hewlett-Packard Company. Under the terms of the deal, Lenovo was allowed to retain the IBM brand name for five years.」 台灣的科技業和聯想電腦的合作也為人熟知,2011年9月底,總部在內湖科技園區的仁寶電腦,和中國聯想合資成立公司製作以聯想個人筆記型電腦為主的電子產品,創下電腦品牌和代工廠合資的第一例。台灣的緯創公司,在日本的工程師團隊(大和實驗室,文中Lenovos research hub in Japan),從2005年以來為IBM的X31、41、X60及X61,就一直致力於聯想小黑機的從裡面到外觀乃至於附加配件的研發設計。現在大致上的Thinkpad系列的標準規格,就是緯創團隊的心血結晶。 筆者目前手邊桌上的三台主機,是兩台Lenovo X240 i5款Windows 10 Pro數位授權升級版,及Yoga book 10 64G eMMC款,翻轉360度的Windows 10 Home版(先保密為什麼去年十月考慮了幾台萬元筆電,包括大陸白牌平板電腦,最後決定是這台),及兩本自己找美國版原廠驅動改裝的Toshiba Portege,一本灌Windows 7 64bit,i5-2520M的R830,和i5第三代的R930,裝Windows 8.1 Pro。另外筆者2015年組裝一台BenQ S31V,包括硬體和軟體的Vista作業系統和Office 2007,花了近三千元。今年三月時在露天賣場「撿到」一台千元的Acer Iconia 8,原裝已回復原廠設定Windows 8 Home 32-bit,拿來看吉澤明步很好用的。 在近五年的筆電市場裡,很可惜Sony出脫了VAIO,Toshiba因為財務醜聞,在海外地區並沒有銷售電腦,只能拿個外觀還算完全的二手機,遙想六七年前自己的無助。筆者記得Windows 7的榮景,於是上個月選擇了從八年前的X220,被評論編輯確立前三名技術的聯想電腦x系列中,原廠有windows 10 驅動程式者(判準是顯示卡的驅動程式)中最便宜的。 Lenovo 產品的好和便利,是廣為網友所讚譽的,概念在產品線Thinkpad、Ideapad、Yoga還有最近三年的Legion電競系列與一年內的Thinkbook。就筆者在第八代至第九代(或第八代修正款)的處理器產品來說,這牌在平價位附近的產品,和其他廠牌比較起來,簡便的Yoga book 有360度翻轉有優勢,ideapad的電腦比較陽春而只有一年保固,比如和筆者在茂訊電腦的ACER三創店經手過的Swift 1 及Aspire 3 比,聯想的機種(除了Yoga翻轉)會比較笨重,算起來服務品質比較不好。所以筆者去年購買比較有特色,又是亞軍機種Yoga 翻轉系列的么弟Yoga book 10。在三創當短命的店員期間,筆者還是不放棄,拿了一台2013年的X240原裝二手機。 當年(2013年)時,聯想的小黑X系列已經出了X1 Carbon系列。當時的小黑主力機種浪潮,也就是鑑賞家所大力讚賞的X230i,230和Ultrabook的X230s,正方興未艾。X240是接續X230s的輕薄,低於1.5公斤的碳纖維機種。另外筆者也快照Yoga 13是PCWorld評論第一名的觸控平板電腦,勝過了同時期的SONY VAIO Duo 11及13(即文中The Long Game 第二、三段所謂以蘋果作為競爭標竿的想法)。筆者算是用銷售觀點在聊,當時剛問市的Windows 8,「開始」的介面換成切換畫面及整排磚塊使人耳目一新,但是也帶來一些不便。各家廠商也配合處理器的進步,競爭的結果明朗,並且隨著觸控面板的成本下降,新的款式推陳出新。筆者的第一台筆電是在2004年買的ACER Travelmate 290,是一台灰色上蓋的鐵殼粗勇機,曾經陪筆者上山下海,渡過一年清華大學和重考轉折,再進入長庚大學醫學系兩年的生活。 聯想就管理名人,及現在的公司策略來說,就是柳傳志和楊元慶。柳傳志是科研人員出身,楊元慶是帶動銷售業務的靈魂人物。聯想在2012之後,主要是設在香港的投資公司當母公司,控制全球的聯想公司內部控管和產品流動。柳傳志選控股公司在香港,的確很聰明,香港彼時為亞洲金融中心,設在這裡上市容易匯集資金,又能收集國際上的業界情報。柳和楊互相截長補短,柳很喜歡作運動健身,楊的口才一流辯才無礙。聯想作全球佈局,除了北京之外,北卡羅萊納的研發基地,在日本有大和實驗室。聯想如果要成為國際品牌,的確先要克服的是企業文化,還要從語言習慣著手改革,比如英語式的思考,另外就是產品年輕活力的形象,瞄準年輕世代速食消費主義的心和脾。從這篇文章得知聯想前幾年一度只專心筆電業務,手機業務出售,但是從Yoga產品線的成功,市場雖認為聯想的再次擴張太過樂觀,楊本人接受經濟學者雜誌訪問的時候,透露出想擴充多樣性的電子產品,在國內還有許多「祕密武器」,比如和富士康那樣的公司仍大部份把生產線擺在中國境內,品質和在亞洲四小龍,或東南亞等新興工業體組裝差不多而工資低廉。 從2014年3月決定購入第一台聯想機,雖然是二手的,到了現在手邊主力就是Thinkpad和Yoga各一台,已經五年半了。因為隔一個月筆者的SONY VAIO SA33掛點了,沒錢整台修(整個33000元),於是靠著前一個月好險有買的X200s(Celeron 723),開始筆者X系列的旅程,過了一年多,然後再購進X200(P8600),過了半年陪著到現在都很好用、裝Vista Business的BenQ S31V,再過了一年半,再購入一台X200也是用了近一年,這三台小黑都是螢幕異常淘汰。直到2019年1月的半年前,購入X201(i5),才三個多月就脫手再換一台X200s。這些X200系列都是灌Windows 7旗艦版。直到上個月弄來X240,為此還在露天買了一個中國公司貨原廠三用包。剛剛(10月14日週一)跑去忠孝東路延吉街口換原廠電池,還去露天賣場的全球3c,弄一顆筆電行動電源20000mah及原廠type-c轉PD方頭的轉接頭的來充(據說小米3代20000mah高配版也可以,拿type-c接轉接頭充)。看著當年以Asia Rising 這本書當背景猜測各家廠商:日本的索尼、東芝、富士通,韓國的樂金和三星,台灣的微星、華碩和宏碁,對比美國的惠普,也只有惠普的Spectre和Elitebook系列,可是單價好高啊.....Yoga機有新台幣三萬多就很耐用輕薄的款式,以後大概就一直用聯想的產品吧。(茶~) 其他相關的放在下一篇討論之中。 Chinese industryFrom guard shack to global giantHow did Lenovo become the world’s biggest computer company?Jan 12th 2013 | BEIJING | from the print edition

LENOVO started humbly. Its founders established the Chinese technology firm in 1984 with $25,000 and held early meetings in a guard shack. It did well selling personal computers in China, but stumbled abroad. Its acquisition of IBM’s PC business in 2005 led, according to one insider, “to nearly complete organ rejection”. Gobbling up an entity double its size was never going to be easy. But cultural differences made it trickier. IBMers chafed at Chinese practices such as mandatory exercise breaks and public shaming of latecomers to meetings. Chinese staff, said a Lenovo executive at the time, marvelled that: “Americans like to talk; Chinese people like to listen. At first we wondered why they kept talking when they had nothing to say.” Two Western chief executives failed to turn things around. By 2008, as the financial crisis raged, Lenovo was bleeding red ink.

Given all this, its recent success is startling. In the third quarter of last year, Gartner, a consultancy, declared Lenovo the world’s biggest seller of PCs, ahead of Hewlett-Packard (HP). Even if HP briefly recaptures the lead in the fourth quarter, the trend seems clear: Lenovo is on a roll (see chart 1). It is number one in five of the seven biggest PC markets, including Japan and Germany. Its mobile division is poised to leapfrog Samsung to grab the top spot in China, the world’s biggest smartphone market. This week it made a splash at the International Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas with whatPC Worldcalled “bullish bravado and a seemingly bottomless trunk” of enticing new products. Lenovo’s rebound raises several questions. How did the firm recover from disaster? Is its new strategy sustainable? And does its rise signal the emergence of China’s first world-class brand? Lenovo’s recovery owes much to a risky strategy, dubbed “Protect and Attack”, embraced by the firm’s current boss. After taking over in 2009, Yang Yuanqing moved swiftly. Keen to trim the bloat he inherited from IBM, Mr Yang cut a tenth of the workforce. He then acted to protect its two huge profit centres—corporate PC sales and the China market—even as he attacked new markets with new products. When Lenovo bought IBM’s corporate PC business, it was rumoured to be a money-loser. Some whispered that Chinese ineptitude would sink IBM’s well-regarded Think PC brand. Not so: shipments have doubled since the deal, and operating margins are thought to be above 5%. An even bigger profit centre is Lenovo’s China business, which accounts for some 45% of total revenues. Amar Babu, who runs Lenovo’s Indian business, thinks the firm’s strategy in China offers lessons for other emerging markets. It has a vast distribution network, which aims to put a PC shop within 50km (30 miles) of nearly every consumer. It has cultivated close relationships with its distributors, who are granted exclusive territorial rights. Conquering India Mr Babu has copied this approach in India, tweaking it slightly. In China, the exclusivity for retail distributors is two-way: the firm sells only to them, and they sell only Lenovo kit. But because the brand was still unproven in India, retailers refused to grant the firm exclusivity, so Mr Babu agreed to one-way exclusivity. His firm will sell only to a given retailer in a region, but allows them to sell rival products. In this way, Lenovo cultivates loyal brand ambassadors, who also give timely feedback on which products and features consumers like. That allows designers to speed up product-development cycles. The firm’s first smartphone flopped, but paved the way for a flurry of hits. Buoyed by success in corporate PCs and China, Lenovo has spent heavily to expand its share of the global PC market, especially in emerging markets. The brand is universally known in China; not so elsewhere. Spending on promotion, branding and marketing rose by $248m in the year ending in March 2012 (though the firm will not reveal the full amount). Acquisitions help, too. In 2011 Lenovo bought Medion, a European electronics firm, for $738m, which doubled its share of the German PC market. The same year it spent $450m to enter a joint venture with NEC that made it the largest PC firm in Japan. In 2012 it paid $148m to buy CCE, Brazil’s biggest computer firm. It is also opening factories in markets, including America, where it is surging. To focus on PCs, Mr Yang’s predecessor sold Lenovo’s smartphone arm for $100m in 2008. Mr Yang bought it back for twice as much the next year. He believes that PCs and other devices will converge, so knowledge of one area will breed expertise in the other. He may be right. Smartphone sales are red hot in China, and Lenovo is now selling mobiles and tablets in several emerging markets. Fourteen quarters in a row, Lenovo has grown faster than the overall PC industry, which shrank by 8% last quarter. A year and a half ago, the firm held double-digit PC market shares in a dozen countries; today, it does so in 34. Alas, there is a tiny problem with Protect and Attack: the attack part is largely unprofitable. In most markets outside China, Lenovo’s mobile phones, tablets and consumer PCs (as opposed to corporate sales of ThinkPads) lose money. “Profit is the long-term goal,” says Mr Yang, “but it helps to have a large revenue base.” He vows to keep investing, regardless of returns, until the firm reaches a roughly 10% share in each of the target markets. Only with such scale is long-term profitability possible, he insists. Wong Wai Ming, the firm’s chief financial officer, is confident Lenovo will eventually double its pretax profit margin of 2%. The long game

In 2009 Mr Yang persuaded the board to give him four years to show results. If allowed to invest, he promised to turn a $226m annual loss into a profit; in fact, the firm posted a profit of $164m last quarter. He vowed to lift annual revenues, then around $15 billion, past $20 billion; they are now $30 billion (see chart 2). He also said he would raise Lenovo’s global market share from 7% to double digits; it is now close to 16%. Lenovo does not simply churn out cheap goods. It is spending heavily on branding, distribution, manufacturing and product development. And alongside its cheap gizmos are many mid-range and some premium gadgets, such as the Yoga, a laptop that cleverly converts into a tablet. On January 6th the firm announced a reorganisation: Lenovo Business Group will make things for cost-conscious consumers, while the new Think Business Group will chase the premium segment. Mr Yang wants the Think brand to compete with Apple; he plans to open fancy showrooms like Apple’s. Lenovo’s culture is different from that of other Chinese firms. A state think-tank, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, provided the original $25,000 seed capital, and still owns an indirect stake. But those in the know say Lenovo is run as a private firm, with little or no official interference. Some credit must go to Liu Chuanzhi, the chairman of Legend Holdings, a Chinese investment firm from which Lenovo was spun out. Legend still holds a stake, but Lenovo shares trade freely in Hong Kong. Mr Liu, one of those who schemed in the guard shack, has long dreamed that Legend Computer (as Lenovo was known until 2004) would become a global star. The firm is strikingly unChinese in some ways. English is the official language. Many senior executives are foreign. Top brass and important meetings rotate between two headquarters, in Beijing and Morrisville, North Carolina (where IBM’s PC division was based), and Lenovo’s research hub in Japan. Only after giving two foreigners a try did Mr Liu push for a Chinese chief executive: his protégé Mr Yang. Mr Yang, who spoke little English at the time of the IBM deal, moved his family to North Carolina to immerse himself in American ways. Foreigners at Chinese firms often seem like fish out of water, but at Lenovo they look like they belong. One American executive at the firm praises Mr Yang for instilling a bottom-up “performance culture”, instead of the traditional Chinese corporate game of “waiting to see what the emperor wants”. Still, the firm has some way to go. It is far too reliant on one market, China. Global investors will not tolerate its meagre profits for ever; some are already grousing. And its global marketing push, which targets go-getting youngsters, is a work in progress. Its slogan in English is not bad: “Lenovo: for those who do”. The firm sponsored the Beijing Olympics, is an official partner of America’s National Football League and has commissioned adverts by a director of James Bond films. Still, David Roman, a former HP and Apple executive who is Lenovo’s chief marketing officer, admits that “none of the successful Chinese firms has yet got a global brand, including us”.

Lenovo uses the hypercompetitive Chinese market as a test bed for products and strategies that are later rolled out globally. That is both a strength and a weakness. If Lenovo is to cement its market-share gains elsewhere, it must go beyond merely copying what works in China. Bad timing makes this problem more daunting. Lenovo has managed to get to the top of the PC mountain at precisely the moment when the mountain appears to be crumbling. Industry sales are shrinking as PCs are made obsolete by other devices. HP has even mooted quitting the business altogether. Some say Lenovo’s costly global expansion will end in tears. Mr Yang disagrees. Indeed, he shows an unfashionable faith in PCs, which are still 85% of Lenovo’s revenues. They will keep evolving, he insists, citing the Yoga. Inventive firms can still profit from them. He gushes about a “PC+” approach, now being tried in China, that adds mobiles, tablets and smart televisions to PCs and connects them all with a local cloud. He also thinks Lenovo has a secret weapon. It has kept a lot of manufacturing in-house (why outsource to Foxconn when you already pay Chinese wages?). Mr Yang believes this in-house expertise gives his firm an edge in product development. But Lenovo must exploit that edge better than it has done so far if it is to compete with a technology powerhouse like Samsung and build a global brand anything like Apple’s. If Lenovo is to become China’s first world-class brand, it must come up with products that consumers are passionate about. In December, as he was honoured as “Economic Figure of the Year” by China’s national broadcaster, Mr Yang described the task ahead for his firm and country: “My dream is that one day China will be more than a world factory…it will be a global centre for innovation.” from the print edition | Business · Recommended · 3 ·

From guard shack to global giant Jan 16th 2013, 12:50

Lenovo, whose strategy of development and source of revenue make the world gain an insight into a new page of PC, is the benchmarking of Chinese manufacturing, especially for innovative investment of restrutcing.

The Economist offered a vision of wax-wane IT giants and a good watching of Lenovo’s development by Liu Chuan-zhi and Yang Yuan-qin, a father-son relationship. Some paragraphs in this article was also reported of Financial Times’ comment and interview with Yang. Besides, Lenovo is a symbol of China’s business, reflected in Liu’s visit to US White House with Hu Jing-tao about 2 years ago.

Indeed, rise or fall of enterprise depends on the style of leader. Instead of Liu’s conservative, Yang’s audacity has Lenovo expose the marginal activities to the market. “Yang’s past 2 decades of Lenovo” described Yang’s trailing evolution, including dilemma and the institution. Yang’s “sales”-oriented is the result of high ranking, making Lenovo a competing company as Toshiba, led by MIT-educated Norio Sasaki and Toshio Masaki, and Sony, directed by Kazuo Hirai from computation-art. Rather than Liu’s “officer”-inclined, Yang takes strategies of high cost of PC, riskier than Sony and Toshiba. When I talked to Yang saying the growth and my friendship with Japan’s both IT giants, Yang felt interested in the success of their value from motherland to world and the flexible management as well in maunfactiring, market and the consumer-driven focus.

With a view to profit, Lenovo still stagnante. Lenovo has built up a reputation for laptop’s brand, including “ideapad” of better routine life and “Thinkpad” of a chase for working efficiency. During the battle of Windows 7, Thinkpad X220 family, with X1, got an acme grade equal to Japanese Sony’s VAIO S and Toshiba’s Protégé, beating American HP’s pride of Pavillion and Dell’s Alienware.

As tablet-oriented Windows 8 and Android 4.0, the panel of crystal-clear HD+ screen is affiliated with almost of each Lenovo’s product, uniquely on the ideapad’s trendy Yoga 13 extending an advantage of tablet in X220 and X230t. No other did type of tablet more than Lenovo. So far, PCWorld’s Sarah Jacobsson Purewal rated Yoga 13 as the best Windows 8 panel, nearly 5 star, with the only competent Sony’s Duo 11. Besides, Lenovo, undaunted by declining demand of tablet, leads tablet evolution while devising its strategy to the extension into Android phone which contained a lady-appealing style similar to last year’s idea of LG’s PRADA phone. It really makes me anxious about Lenovo’s future owing to Yang’s too much optimism.

According to “Asia Rising” by Jim Rohwer, then Economist executive editor, succeeding in brand name is always a formidable challenge of high-tech company. In Asia, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have respective stories. Both Japanese, Sony’s Akio Morita and Toshiba’s Toshio Doko, occupied electronic market in the developed nation for a long time. Sony’s Walkman and VAIO, with Morita’s expectation, prevail while seeing the growth of Taiwan’s Acer and Asus as well as South Korea’s Samsung and LG.

Stan Shih (Shih Zhen-rong), Taiwans father of brand, and Gao Qing-yuan of Uni-President set good examples of progress due to westernized culture of enterprise. It is Travelmate 290, the main product of Acer in 2004, that was my first laptop. BenQ’s seperation from Acer, by Lee Quan-yao in 2001, processed a cruel blow to the brand operation owing to the failure to merge Siemens in 2006. Besides, Steve Chang’s (Chang Ming-cheng) Trend Micro and Cherr Wang’s (Wang Shieh-hung) HTC also own impressive brands. Samsung’s debut was a little later than Acer, from a pot-noodle vendor, and has less stories of growth but achieves higher rank in brand - 8th in 2012

Lenovo, Haier, Huawei and ZTE are relative young brand. The first successful China’s brand is China Mobile, at world’s rank 5th in 2007. Lenovo has chaired the majesty of PC, even having cooperated with Japan’s NEC last June with a fresh foorprint emerging plus EMC’s partnership. With regard to revenue, Lenovo continues to battle with Acer and Dell since “Thinkpad” walked into Amercian market in 2006.

Realizing a dream is also uneasy, as Stan Shih announced the failure of the plan on Taiwans “Silicon Valley”. For a healthy environment of investment, outside or public infrastructre is planned by government with demand of market while inside knowledge, such as management of supply chain, improves with innovation. Recently, Taiwan’s Quanta moved OEM product line of Toshiba, Acer and HP from Shanghai to Chongqing for lower cost of PC. With a view to unit of selling PC’s ratio, at 2012’s 4th quarter in the world, HP led 16.7% and Lenovo got 16.5% of 89.79 mil units according to Nikkei last week. For a period, Lenovo paid attention to hardware more than software, ensuring the quality controlled on its own. Now goes shaking it, of Arashi’s or Ayumi Hamasaki’s ver., more than shacking up with following the example of Japan’s IT.

Recommended 4 Report Permalink

以下是「科技新報TechNEWS」一篇相關的「國進民退」報導,不看到這篇,筆者還以為柳傳志先生過世了ㄟ?怎麼都沒露什麼面的。 國進民退是日本經濟新聞網中文版,在2015年以後所創的名詞,因為習近平在黨政權勢穩固,厲行馬克思主義的國有論,以壓制自由派經濟或政治學者並且深入企業,要求企業成為黨組織的經濟生產單位。從2018年後,隨著生產面的結構改革,黨對企業生產力的監督漸趨嚴密,還會要求外國企業成立工會黨部。其實說起來真的會增進效率嗎?還是來晃點一下,共黨中央也搞快閃活動了嗎?不知這波,於去年王健林捐地事件之後,一年內連換三個中國企業要角,還有更多的政策要出台? https://technews.tw/2019/09/24/private-enterprises-exit-lenovo-said-that-liu-chuanzhis-resignation/ 繼馬雲、馬化騰卸任之後之後,外界一直對中國民營企業家動向相當關注,如今傳出聯想創辦人柳傳志也不再是聯想控股法定代表人,引發相當多的討論。

現年 75 歲的聯想控股創辦人暨董事長柳傳志,在 23 日傳出將不再是聯想控股(天津)的法人代表。據中媒報導,柳傳志卸任後,聯想控股法人代表及董事長將由深圳市瑞龍和實業法人代表張欣接任。其他董事會人事調整還包括,唐旭東、寧旻退出董事行列,郭永蕾、李蓬新增為董事。此人事換血的動作,被認為是中共「國進民退」的布局。 據消息指出,柳傳志一共登記擔任近 17 家企業的法定代表人,但原先由柳傳志擔任代表的公司,除了聯想控股之外,其餘都已顯示「遷往市外」或「註銷」。不過聯想控股指出,天津公司只是聯想控股的一個平台公司。旗下許多子公司、平台公司都根據業務需要進行合作、調整等,此舉只是企業正常的業務安排。 當然這也並非空穴來風,儘管聯想集團是民營企業但背後除了聯想控股外,也有如中國科學院等國營機構注資。且在此時期,中共當局又以協助企業為名,派出不少政府事務代表進駐民營企業,如阿里巴巴、浙江吉利控股等近百家知名中國民企,被認為是加強監管的鋪陳,甚至是接管的前奏。且連外資企業也有類似消息,被迫令中共政黨代表進入公司治理。目前阿里巴巴聲明則表示,政府官員起到的是政府和民營企業之間的橋樑作用,並不會干擾公司運作。 此情事也可能與中共近年來提倡的國企混改布局有關,計畫要利用民間資本來強化國營企業競爭力,參與市場競爭。並強調,這不是公私合營,更非國進民退。不過去年聯想就因 5G 投票問題,被中國輿論撻伐,甚至被冠上賣國的帽子,如今有這樣的消息,當然引人遐想,值得繼續觀察。 (首圖來源:shutterstock)

|

|||

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |