字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2019/05/19 01:52:53瀏覽56|回應0|推薦0 | |

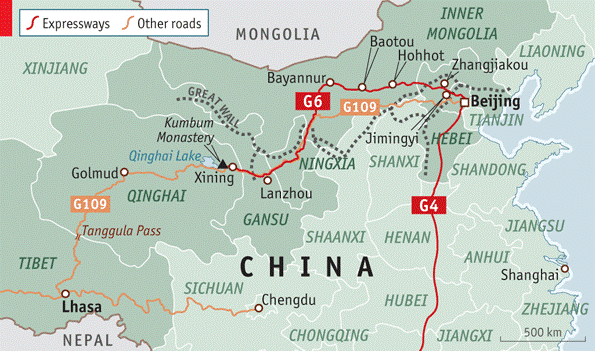

這篇是當年2012-13的耶誕暨新年特刊的選文,筆者大概看過有興趣的,但沒有作回覆。原雜誌文章提到內蒙和西部地區的公路建設。 China’s motorwaysGet your kicks on Route G6China is building a motorway across the Tibetan plateau. For some, reaching Lhasa by road is the ultimate dreamDec 22nd 2012 | ON THE BEIJING-TIBET EXPRESSWAY | from the print edition

LIU BO’S wife begged him not to do it. She said he was ill-prepared for the dizzying altitude and the treacherous roads. He would be on his own, possibly hundreds of kilometres from help if anything went wrong with him or their Fiat Bravo. But Mr Liu was determined. The couple plan to have a child next year. Now, he felt, was the time to drive the family car thousands of kilometres across China to Tibet. He recalls telling her: “There’s only one question about going to Tibet. It is, ‘When?’ Nothing else is a problem. All you need is determination. There’s not much to prepare.” His list: some money, some clothes and medicine to cope with altitude sickness. Mr Liu, a 32-year-old car salesman, lives in a suburban commuter-belt north of Beijing; a member of a middle class that barely existed until the end of the 20th century. A few hundred metres from his home is the G6 Expressway, part of a web of motorways that has expanded just as exponentially: from around 3,200 kilometres (2,000 miles) in 1996 to 85,000km at the end of 2011. In a couple of years it will surpass the length of America’s interstate network. China overtook America in 2009 to become the world’s biggest consumer of cars. This combination of a new middle class with cars and new high-speed roads is begetting exotic dreams. For growing numbers like Mr Liu, Tibet is where the highways lead. They see it as a world away from their smog-shrouded, car-jammed, money-driven cities: high, remote, mysterious, alluring yet forbidding, its air brilliantly clear yet menacingly starved of oxygen. There is no shortage of challenging destinations for drivers in China, but Tibet is widely regarded as the ultimate one. China’s rapidly growing car-hire industry plays to such fantasies. “Follow your heart, not your route,” says a poster in a Beijing rental office. In January China Auto Rental, one of the biggest such firms, opened an office in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital. The G6 itself shares the dream. Since the mid-1990s it has come together, bit by bit, each stretch with different names. Then, two years ago, they all took on the same one: the Beijing-Tibet Expressway. The road does not yet make it to Tibet. It sweeps across northern China, veers southwards, climbs up onto the Tibetan plateau and then peters out in the high-altitude grasslands, about 1,800km from Beijing near Xining, the capital of Qinghai province. It is still only halfway to its longed-for destination, Lhasa, and hundreds of kilometres short of the border of Tibet proper. But it and other expressways extend close enough to Tibet to lure distant car-owners onto the plateau for the final assault by old, narrow roads across mountain passes. The G6 keeps its users’ hopes up with signs promising the holy grail. One in Beijing tantalisingly says, “Lasa [sic] km” with the distance taped over as if ready to be revealed when at last the G6 makes it there. On excursions out beyond the Great Wall, Mr Liu used to joke to his wife that all they had to do was keep on going on the G6 and they would reach Tibet. Such is the extent and complexity of the new motorway network that Beijing drivers have a choice of roads before they join, if they haven’t already, the G6 for the ascent into the yak pastures. In the end when Mr Liu set out in September it was along the Beijing-Hong Kong-Macau Expressway, the G4. Mr Liu chose a route that would take him through cities in central China where he knew he would enjoy the food. Most of the territory traversed by the G6, the northernmost of the options, is of little interest to Beijing gastronomes. One of the biggest attractions is the headquarters in Baotou, a city in Inner Mongolia, of Little Sheep, a hotpot chain, where customers are entertained with an array of television monitors endlessly repeating a video of sheep carcasses moving down a production line and being cut into wafer-thin slices. Heading for the plateau Tibet-bound drivers usually try to complete the expressway part of the route as quickly as possible. This correspondent elicited repeated surprise during his recent journey along the length of the G6 by his insistence on tackling a mere 300km a day. (Regrettably he was refused permission to proceed into Tibet: the authorities said it would be too dangerous because of possible rain, a euphemism for too dangerous because of possible anti-Chinese protests that they do not want journalists to see.) But taking it slowly is advisable; China’s roads are among the most lethal in the world. A stretch of the G6 in Beijing is known as the “Valley of Death” because of a tendency among vehicles speeding downhill towards the city to plunge off the sides of the elevated sections. As the photograph above shows, wrecked cars are sometimes put on display by roadsides as a warning to drivers (the message on the pole reads “cherish life, drive safely”). At motorway service stations, billboards provide gory details of accidents on nearby stretches, along with photographs of crushed bodies. The Beijing-Tibet Expressway, despite its name, was not initially built with Tibet in mind. After leaving Beijing it heads west for several hundred kilometres, stubbornly refusing to dip south towards the Tibetan plateau. This is because its primary purpose along this segment is economic: speeding up the flow of coal and other minerals from the mines of Inner Mongolia towards China’s coast. When at last the road heads away from the sparsely populated grasslands of Inner Mongolia, the lorries thin out dramatically. Along this stretch the road’s purpose becomes more political: creating a symbolic umbilical cord linking the capital with far-flung ethnic groups. So sparse is traffic that it often seems more cars are being transported on occasional lorries than are on the road itself. It’s grim back east Not so on the first east-west stretch near the capital. In August 2010 this part of the G6 hit global headlines with what some newspapers called the world’s longest traffic-jam on the Beijing-bound lanes. It backed up for more than 100km (see photo below), and consisted mainly of coal lorries snarled by road works and accidents. It took ten days to clear. At that time half of China’s coal-carrying lorries were said to be servicing Inner Mongolia’s mines, with many of them plying the G6. Heading toward the mines, this correspondent was scarcely impeded (no doubt helped by a fall in demand for coal as China’s economy slows). Most day trippers from Beijing head no farther along the G6 than the Great Wall in the city’s outskirts, but growing numbers venture beyond into Hebei province. Here the road roughly follows the route along which the Empress Dowager Cixi fled when allied Western armies invaded China in 1900 to relieve the siege of Beijing’s embassies by xenophobic Boxer rebels. One of the places where she is said to have stopped for the night, a town called Jimingyi, lies close to the expressway. Its walls and rustic imperial-era architecture remain remarkably well preserved. Locals, capitalising on Beijing’s motoring boom, now charge visitors 40 yuan, about $6.40, to enter. What is said to be Cixi’s bed, in a tiny room off the courtyard of a peasant house, can be slept on for 50 yuan a night. The next big city, Zhangjiakou, has also benefited from Beijing’s car boom. In the winter car owners in the capital flock to its ski resorts. Beyond that is the monotony of Inner Mongolia. Hohhot, the provincial capital, is a draw for some, who use it as a base for striking out from the G6 into the grasslands, to ride horses, sleep in ersatz Mongolian tents, eat a lot of lamb and sing songs under stars rarely seen in Beijing’s haze. Hohhot is on the outer perimeter of what Zhijun Chu of Lingtu, a maker of satellite-navigation software, says is the 500km comfort-zone for excursions by motorists. Such software has played a big role in drawing Chinese drivers out of their hometowns. In a country where detailed maps are often regarded as state secrets (until recently many villages were not even marked on them), navigating by map is not a skill that many learn. As Peter Hessler, an American journalist, wrote in a 2010 book, “Country Driving”, about his car journeys in China: “Even professional drivers with years of experience could be hopelessly confused by a simple atlas.”

It is a slow toil through much of Inner Mongolia, as Zheng Jie found when she drove along the G6 with her husband and father on their way back from Tibet in October. Ms Zheng, who runs a headhunting firm in Beijing, laments what she calls a “blank space” of road-themed music to accompany China’s fast-developing car culture. There is no equivalent yet of Willie Nelson’s “On the Road Again” to get drivers in the mood (she and her passengers spent much of their journey listening to syrupy new-age music). There is sadly little relief on the G6 in the form of what might be called highway haiku: garbled English translations on motorway signs that in their highest form have a poetic quality matching the rhythm of the road. Only one example worthy of the description offers itself (albeit hypnotically repeated) on the G6 Tibet-bound: Rain or snowy day Service stations offer little solace either. There are no branded fast-food chains on the G6, the catering norm being lukewarm slops served in an all-you-can-eat buffet for 30 yuan. Truckers slumped over this fare appear to enjoy the sight of a lone foreigner eating his food. (So rare are foreigners on remote parts of the G6 that in one town in Inner Mongolia police were deployed to follow this correspondent in an unmarked car until he was back on the motorway.) The shopping opportunities are no more enticing: usually just a small snack shop with products ranging from cheap hard spirits to shrink-wrapped donkey and dog meat (“Eat it a hundred times and you’ll never get sick of it” says a slogan on the packaging). One, however, deviates from the standard offering with a rack full of samizdat soft pornography, including titles such as “New Game in the Boudoir” and “Secret Extramarital Affairs”. As the road arcs southward, following the course of the great bend of the Yellow River, occasional travellers can be found in the near-deserted service stations. Around 850km along the G6 near the city of Bayannur, a couple from Beijing rested at a pit stop in their Chinese-made Kia, a South Korean brand. They were about to strike off westward from the motorway, out across the Gobi desert. “It was all dirt track in the 1980s,” says the man, looking in admiration at the near-empty forecourt (except for a stray three-legged Pekingese) and the road beyond. Signs instruct motorists: “Everyone has responsibility for cherishing the road”. He, at least, needed no telling. The couple were getting their G6 kicks before the week-long National Day holiday in early October, when tourism-related prices often leap. This year, for the first time, expressway tolls were abolished during the break. These can make travel by road in China more expensive than flying. Lin Miao, the husband of Ms Zheng, the headhunter, drove from Beijing to Lhasa and back in their GM Chevy Equinox. He says the family could have flown to Europe for the same cost. Into the highlands Close to where the G6 ends in Qinghai, a near-obligatory stop for motorists is Kumbum Monastery, a centre of Tibetan Buddhism. Its car park is sprinkled with licence plates from far and wide. Chinese officials often accuse Westerners of romanticising Tibet. But the region’s mystique also exerts a powerful pull on urban Chinese. The Westerners who settle in Dharamsala, the Indian town that is home to the Dalai Lama, to soak up the wisdom of Tibetan Buddhism have their counterparts in China: members of the middle class who, although not quite hippies, see Tibet as an oasis of calm and spiritual purity, unblemished by the turmoil and ruthless competition of China’s economic transformation. Global Times, a Beijing newspaper, said travelling to Tibet was like “seeking the primal freedom of life”. Some Tibetans would grimace at the irony. In recent months dozens of them have set themselves on fire in protest against Chinese rule, prompting an escalation of security measures across the region. Pan Bing, who works for a foreign telecommunications firm in Beijing and recently drove all the way to Lhasa, says the convoy of cars with which he travelled in and out of Tibet in April was stopped many times for identity checks at police checkpoints. Such irritants appear not to deter private motorists, however. After arriving in Lhasa, desperate for a decent meal, Ms Zheng’s party headed for one of the city’s best Tibetan restaurants. It was full of tourists from the Chinese interior. As they swapped tales of how they had got to Tibet (plane and train are still by far the most common means), they discovered that around 30 people there had driven from Beijing. In, out and shake it all about, online Enthusiasts have developed a shorthand for describing the different routes into Tibet using the Chinese characters jin (enter) and chu (exit). These abbreviations convey to those in the know just how daring the driver has been. To say one has qing jin qing chuis relatively little to boast about. It means one has entered and left Tibet through Qinghai province (qing) along the old 1950s-built G109, which takes over where the G6 ends. This is the safest route. But Xu Jing, who runs a travel firm, Tibetdrive.com, saysthat even on this route “100%” of her clients get altitude sickness as they cross the Mount Tanggula pass at 5,231 metres (17,160 feet) above sea level. This is a fraction higher than the oxygen-starved base camp on the Chinese side of Mount Everest (itself an increasingly popular destination for domestic tourists). A common technique is for motorists, armed with oxygen canisters, to cross this in one gruelling 800km stretch in order to start and finish the day at more manageable altitudes (Chinese visitors often have an exaggerated fear of Lhasa’s 3,700-metre elevation: many walk in slow motion as they emerge from Lhasa’s airport, believing exertion might trigger a dangerous reaction). Ms Xu says about half of her firm’s customers choose to go in convoy, a precaution many prefer given the risk of drivers being rendered unfit by the altitude. Higher up the hierarchy are those who opt for chuan jin qing chu: entering from Sichuan (chuan) and leaving through Qinghai (qing). The road from Sichuan is not as high, but also not as smooth: a series of switchbacks, often blocked by rock slides, with rain, snow and lorries posing additional hazards. Ms Zheng’s car entered this way. It took them hours to crawl along one stretch of the highway that was no more than gravel with deep potholes. Those who choose xin jin, entering from the far western region of Xinjiang, can brag even more, whichever way they chu. On his no-bragging-rights journey, this correspondent met one man in Qinghai heading with visible relief back to Beijing. He described his xin jin leg as a “near-death” experience that he would never repeat: three days of high-altitude agony during which he was unable to eat or sleep. Having endured such travails, car owners like to get online to show off their pictures (if they haven’t managed to post them en route: spotty 3G-mobile coverage on the plateau is a frustration for China’s avid bloggers). Within a year of setting up an online forum for drivers to Tibet, Ms Xu’s company had 30,000 registered users. It now has some 200,000, she says. Ms Xu says she and her friends got more than 100,000 hits on their postings about their own drive to Lhasa three years ago. Mr Liu, the car salesman, wants to trade up his Fiat Bravo for a four-wheel drive and do Tibet again: this time aiming for the chuan jin qing chu distinction. “If someone has a four-wheel drive they have to drive to Tibet,” he says. Not to do so would be “like having skis and not going skiing”. Now the only question is whether the G6 expressway itself will ever make it. Officials have a huge political incentive to make sure it does, Tibet being the only Chinese province unconnected to the motorway network (apart from the island of Taiwan, which China regards as one of its provinces and also dreams of one day linking to by motorway). But Chinese scientists say that extending the G6 into Tibet would be an even greater technological challenge than laying a railway across it, which China achieved in 2006. Such an expanse of heat-absorbing tarmac would exacerbate the damaging effect of temperature variations on stretches running over frozen soil. The impact is evident on the narrow G109. Xinhua, a state news agency, described one stretch of this in 2007 as looking as if “some giants had smashed it angrily with enormous hammers”. Paradise lost? Another problem the government might be considering (but probably isn’t) is the potential social and environmental impact. The railway encouraged a huge increase in tourism to Tibet, which rapidly widened the wealth gap in Lhasa between ethnic Hans and local Tibetans, who felt they were being marginalised. Grievances over this fuelled the riots that erupted in 2008. Environmentalists were enraged by the railway’s construction. They would feel the same about a motorway. On his trip this correspondent drove as far as Qinghai Lake. Since the last segment of the G6 enabling a clear run from Beijing to Xining was completed in 2005, the easy access it offers to this vast saltwater expanse has turned the lake, which is sacred to Tibetans, into a tourist magnet. Around 860,000 visitors came last year, up from 630,000 in 2010. A black-clad motorcyclist, in a departure from the surly norm of drivers in China, waves as he overtakes, roaring towards its shore: his bike’s plates are from Beijing. On the Tibetan plateau, the road forges instant comradeship. No date has been set for extending the G6 into Tibet, but work has recently begun on building a 400km link from west of Qinghai Lake to Golmud, the last big town before the Tibetan border and the tundra beyond. It is due for completion in three years, at a cost of $1.6 billion. A middle-class dream of Lhasa by expressway is very much in the making.

Coal country

from the print edition | China

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |