字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2019/05/11 18:55:17瀏覽103|回應0|推薦0 | |

「水往低處流、人往高處爬」。筆者在當個禮拜興致還不錯,回憶起張黎執導的「走向共和」的開頭。袁世凱以一個山東巡撫的身份,由於在義和團事件組東南自保,和列強還有一定的關係。這句是袁氏送給三國大使的話,果然十年不到,原似韜光養誨的袁氏高升,並縱橫捭闔中國軍政界,利用清廷帝制和新生共和軍的矛頓作居間拿到國家元首,但又舉國反對他的野心,稍縱即逝。說來筆者又賭對了兩岸政治一次,除了在2002年猜過阿扁有很大的機會連任,怎麼習近平在2018年修憲時,果然是差一些就是搞了終身制。 標題是「隱惡揚善」的翻譯。說到中共的對外宣傳,還是按照基本的中國人的道理來走,從毛澤東井崗山打天下到所謂對共產黨教義作中國本土化的太子黨執政,對中國全境進行合理合法的統治,不外乎是一直地尋求支持,一再地說明教義及倫理。 這篇文章見微知著的說明習近平從浙江「下江村」的領導實習經驗,往前回朔至山西北部人民公社,往後展望在十年左右「翻兩番」中國經濟應為如何走向。筆者先回應在中國古至今大部份政治上而言,權力是唯一的事實,永恆不滅的標準,若說儒家還是馬列主義,其實是政治在中國大部份時候,權力的運作是大部份民眾看不見也很難參與的。 筆者引用吳敬漣博士的「當代中國經濟改革」(美商麥格羅希爾出版正體中文版),其歸納的中國經濟數據是最詳實而分析權威者,透過數據說明了中共制定中國經濟政策的優缺點。筆者接著回顧江澤民及胡錦濤歷任的危機和挑戰,前者為派系的挑戰,後者是結構貪汙的問題,又到了這篇的一年內是有重大刑案的涉及。當時開始興盛的YOUTUBE影片網站主們,熱烈討論曾慶紅的「密室造王說」,把習近平拱上了唯一的世代權威交接者,積分超越李克強,使原來的共青團派升遷變困難。 若以一首歌來形容胡錦濤的治世,筆者是拿現代化又復古風並存的周杰倫和費玉清「千里之外」,是2006年8月底出品。中國大陸在胡錦濤、溫家寶的帶領下,許多民初的人文和風景又復甦了一些,中國的銳變在各領域、各族群、大小城市間開展開來,忙祿又充實的中產階級及市民意識興起,多元文化和職業分化進行著,「依然范特西」的JAY式中國風大行其道。筆者當時剛從大學一年級升上二年級,但又好像重摔了一下,及至數年後,祖國的呼喚迴蕩在耳邊,風間有了陌生又熟悉的聲音...... China’s new leadershipVaunting the best, fearing the worstChina’s Communist Party is preparing for its ten-yearly change of leadership. The new team could be in for a rough rideOct 27th 2012 | BEIJING AND XIAJIANG VILLAGE | from the print edition

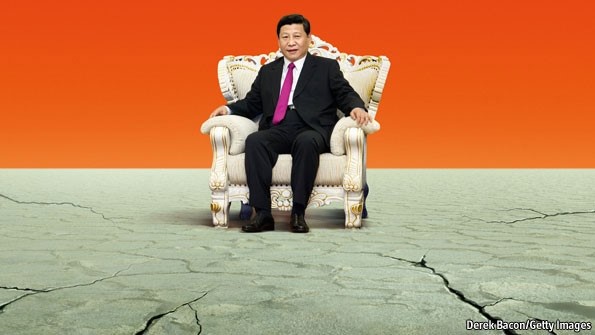

FEW Chinese know much about Xi Jinping, the man who will soon be in charge of the world’s most populous country and its second-largest economy. This makes the inhabitants of the remote village of Xiajiang, nestled by a river amid bamboo-covered hills in the eastern province of Zhejiang, highly unusual. They have received visits from Mr Xi four times in the past decade. Impressed by his solicitude, they recently erected a wooden pavilion in his honour (above). During his expected decade in power, however, Mr Xi will find few such bastions of support. The China he is preparing to rule is becoming cynical and anxious as growth slows and social and political stresses mount. Mr Xi’s trips to Xiajiang, a long and tortuous journey past tea plantations and paddy fields in a backward pocket of the booming coastal province, were part of his prolonged apprenticeship for China’s most powerful posts. They took place while Mr Xi was the Communist Party chief of Zhejiang from 2002 to 2007. He had just turned 50 when he made his first trip, continuing a tradition started by his predecessor as Zhejiang’s chief, Zhang Dejiang, who now also looks likely to be promoted to the pinnacle of power in Beijing. Mr Zhang’s idea was to visit a backward place in the countryside repeatedly to monitor its progress over time. Xiajiang was the lucky target. When Mr Xi adopted it, villagers found themselves with a sugar daddy of even greater power: the scion of a revolutionary family. His father, Xi Zhongxun, was one of Mao’s comrades in arms, but later fell out with him and spent much of the next 16 years in some form of custody. Since 2007, when Mr Xi was elevated to the Politburo’s Standing Committee, no one has ever seriously doubted that he was being groomed for the very top. Villagers say Mr Xi helped Xiajiang secure funding and approvals for its projects, which included pooling village land to grow grapes and medicinal plants. It is unclear how much Mr Xi was actively involved, or whether his mere interest in the village inspired lower-level officials. It is known that he took a keen interest in converting the village to the use of biogas. “A master of building methane-generating pits,” Mr Xi jokingly called himself on one visit, referring to his similar efforts back in the 1970s during the Cultural Revolution when he worked in a People’s Commune in northern Shaanxi. Recalling his dusty labours there, he wrote in 1998: “I am a son of the yellow earth”—as if he, a “princeling” of one of Communist China’s most powerful families, was just a common man. Mr Xi kept in touch with Xiajiang’s officials even after he became President Hu Jintao’s heir-apparent. A large copy in bronze of one of his letters, written in May last year, adorns the new pavilion. “I hope you will thoroughly implement the concept of scientific development,” he urges them. By this he means development that is fair to all, environmentally friendly and sustainable.

Xi, the new enigma

In a room in the village headquarters, Mr Xi’s face is all over the walls. Officials have recently given a few honoured residents large portraits of Mao Zedong to hang in their living rooms, as well as photographs of Mr Xi touring the village. (The two men look fairly similar, with their portly frames and full cheeks.) The exhibition calls the village “Happy Xiajiang”. At the party’s 18th congress, which begins on November 8th andis expected to last about a week, it is a foregone conclusion that Mr Xi will be “elected” to the party’s new central committee of around 370 people. This will then meet, immediately after the congress, to endorse a list of members of a new Politburo. Mr Xi’s name will be at the top, replacing that of Hu Jintao as general secretary. He might also be named as the new chairman of the party’s Central Military Commission, replacing Mr Hu as China’s commander-in-chief. In March next year, at the annual meeting of China’s rubber-stamp parliament, the National People’s Congress, he will be elected as the country’s new president. Mr Hu’s speech at the 18th congress will thus be his swansong (even if he keeps his military title for a year or two, as predecessors have done, he will probably stay out of the limelight). It will be suffused with references to the signature slogans of his leadership: “scientific development”, “building a harmonious society”, “putting people first” and generating “happiness”. (Indices measuring which have become a fad among officials in recent years, their credibility somewhat undermined by repeated findings that Lhasa, the troop-bristling capital of Tibet, is China’s happiest city of all.) Xiajiang knows the slogans well. A billboard on the edge of the river urges villagers to “liberate [their] way of thinking, promote scientific development, create a harmonious Xiajiang and bring benefit to the masses”. Mr Hu will proclaim success in endeavours like these across the country. Having presided over a quadrupling of China’s economy since he took over in 2002, he has reason to crow. In the same period China has grown from the world’s fifth-largest exporter to its biggest. Mr Hu, aided by his prime minister, Wen Jiabao (who is also about to step down), can also point to progress towards helping the poor. During the past ten years fees and taxes imposed on farmers, once a big cause of rural unrest, have been scrapped; government-subsidised health insurance has been rolled out in the countryside, so that 97% of farmers (up from 20% a decade ago) now have rudimentary cover; and a pension scheme, albeit with tiny benefits, has been rapidly extended to all rural residents. Tuition fees at government schools were abolished in 2007 in the countryside for children aged between six and 15, and in cities the following year (though complaints abound about other charges levied by schools). In urban China there have been improvements, too. These include huge government investment in affordable housing. A building spree launched in 2010 aims to produce 36m such units by 2015 at what China’s state-controlled media say could be a cost of more than $800 billion. Over the past five years more than 220m city-dwellers without formal employment have been enrolled in a medical-insurance scheme that offers them basic protection (though, like the rural one, it provides little comfort for those needing expensive treatment for serious ailments and accidents). This means that 95% of all Chinese now have at least some degree of health cover, up from less than 15% in 2000. Mr Hu is also likely to highlight China’s growing global status: its rise from a middle-ranking power to one that is increasingly seen as second only to America in its ability to shape the course of global affairs, from dealing with climate change to tackling financial crises. Its influence is now evident in places where it was hardly felt a decade ago, from African countries that supply it with minerals, to European ones that see China’s spending power and its mountain of foreign currency as bulwarks against their own economic ruin. It is even planning to land a man on the moon. In July the People’s Daily, the party’s main mouthpiece, called the last decade a “glorious” one for China. “Never before has China received so much attention from the world, and the world until now has never been more in need of China.” The people’s mistrust Unfortunately for Mr Hu, as well as for Mr Xi, the triumphalism of the People’s Dailydoes not appear to be matched by public sentiment. Gauging this is difficult; but the last three years of Mr Hu’s rule have seen the opening of a rare, even if still limited, window onto the public mood. This has been made possible by the rapid development of social media: services similar to Twitter and Facebook (both of which are blocked in China) that have achieved extraordinary penetration into the lives of Chinese of all social strata, especially the new middle class. The government tries strenuously to censor dissenting opinion online, but the digital media offer too many loopholes. One of the greatest achievements of the Hu era (though he would claim no credit) has been the creation, through social media, of the next best thing to a free press. China’s biggest microblog service, Sina Weibo, claims more than 300m users. This is misleading, since many have multiple accounts. But nearly 30m are said to be “active daily”, compared with 3m-4m copies of China’s biggest newspaper, Cankao Xiaoxi. Chinese microbloggers relentlessly expose injustices and attack official wrongdoing and high-handedness. They help scattered, disaffected individuals feel a common bond. Local grievances that hitherto might have gone largely unnoticed are now discussed and dissected by users nationwide. Officials are often taken aback by the fervour of this debate. Sometimes they capitulate. In September photographs circulated by microbloggers of a local bureaucrat smiling at the scene of a fatal traffic accident, and wearing expensive watches, led to his dismissal. Many of the most widely circulated comments on microblogs share a common tone: one of profound mistrust of the party and its officials. Classified digests of online opinion are distributed among Chinese leaders. They pay close attention. Stemming this rising tide of cynicism will be one of Mr Xi’s biggest challenges. Dangerously for the country’s stability, it coincides with growing anxiety among intellectuals and the middle-class generally about where the country is heading. Even in the official media, articles occasionally appear describing the next ten years as unusually tough ones for China, economically and politically. In August official-media websites republished an article, “Internal Reference on Reforms: Report for Senior Leaders” that was circulated earlier in the year in a secret journal. Its warning about the “latent crisis” facing China in the next decade was blunt. “There are so many problems now, interlocked like dogs’ teeth,” it said, with dissatisfaction on the rise, frequent “mass disturbances” (official jargon for protests ranging in size from a handful of people to many thousands) and growing numbers of people losing hope and linking up with like-minded folk through the internet. It said these problems could, if mishandled, cause “a chain reaction that results in social turmoil or violent revolution”. The author, Yuan Xucheng, a senior economist at the China Society of Economic Reform, a government think-tank, proposed a variety of remedies. They ranged from the liberal (such as easing government controls over interest rates, which act as a way of subsidising lending to state enterprises at the expense of ordinary savers) to the draconian (beefing up the police and “resolutely” clamping down on dissidents using “the model of class struggle”). The next ten years, argued Mr Yuan, offered the “last chance” for economic reforms that could prevent China from sliding into a “middle-income trap” of fast growth followed by prolonged stagnation. Mr Xi is likely to share his concerns about the economy. They are similar to those raised in a report published in February by the World Bank together with another government think-tank, the Development Research Centre of the State Council. This rare joint study, produced with the strong backing of Li Keqiang (who is expected to take over from Mr Wen as prime minister next March), also raised the possibility of a “middle-income trap” and called for wide-ranging economic reforms, including ones aimed at loosening the state’s grip on vital industries, such as the financial sector. It gave warning that a sudden economic slowdown could “precipitate a fiscal and financial crisis”, with unpredictable implications for social stability (though World Bank officials tend to be optimistic that China can avoid a slump). Dangers pending Mr Xi is being besieged from all sides by similar warnings of possible trouble ahead. A recurring theme of commentary by both the “left” (meaning, in China, those who yearn for more old-style communism) and the “right” (as economic and political reformers are often termed) is that dangers are growing at an alarming rate. Leftists worry that the party will implode, like its counterparts in the former Soviet Union and eastern Europe, because it has embraced capitalism too wholeheartedly and forgotten its professed mission to serve the people. Rightists worry that China’s economic reforms have not gone nearly far enough and that political liberalisation is needed to prevent an explosion of public resentment. Both sides agree there is a lot of this, over issues ranging from corruption to a huge and conspicuous gap between rich and poor. Hu Xingdou of the Beijing Institute of Technology says it has become common among intellectuals to wonder whether 70 years is about the maximum a single party can remain in power, based on the records set by the Soviet Communist Party and Mexico’s Institutional Revolutionary Party. China’s party will have done 70 years in 2019. Chinese intellectuals and officials have a habit of worrying. They did a lot of it after the Tiananmen Square protests, as instability swept the communist world. In the early 1990s many wondered whether China could reach the end of the decade without experiencing another upheaval itself. But the forecasters of looming chaos proved dramatically wrong. They failed to predict the economic spurt in 1992 that propelled China free of its planned-economy moorings. By the turn of the century this momentum began to create a middle class whose members had a stake in keeping the growth-loving party in place. This middle class, however, is now beginning to worry about protecting its gains from the whims of law-flouting officialdom and the caprices of the global economy. It frets about the environment and food contaminated with chemicals. Even if China’s economy, as some analysts expect, continues to grow at strong single-digit rates for the rest of the decade, most agree that the heady double-digit days of much of the past ten years are over. China’s media censors do not want the supposed difficulties of the next few years blamed on the outgoing leadership. They were very unhappy with an essay written by one of the party’s own senior theoreticians which was published in September on the website of Caijing, a Beijing magazine. The scholar, Deng Yuwen, who is a senior editor of the party journal, Study Times, wrote that the Hu era had possibly created more problems than it had solved. The party, he said, was facing “a crisis of legitimacy”, fuelled by such issues as the wealth gap and the party’s failure to “satisfy demands for power to be returned to the people”. Mr Deng’s views were deleted from the website within hours. On his Sina Weibo microblog (with around 6,600 followers: not bad for someone whose job is to write for party insiders) he describes himself as one who “cries out for freedom and struggles for democracy”. Despite the censors, Mr Deng’s views continue to be echoed by party liberals. In mid-September the National Development and Reform Commission, the government’s economic-planning agency, convened a meeting of some 70 scholars in Moganshan, a hillside retreat once beloved of Shanghai’s colonial-era elite. “I strongly felt that those with ideals among the intelligentsia were full of misgivings about the situation in China today,” said Lu Ting, an economistat Bank of America Merrill Lynch, who took part. Several of the scholars, he wrote for the website of Caixin, a Chinese portal, described China as being “unstable at the grass roots, dejected among the middle strata and out of control at the top”. Almost all agreed that reforms were “extremely urgent” and that without them there could be “social turmoil”. Liberals have been encouraged by the downfall of Bo Xilai, who was dismissed as party chief of Chongqing, a region in the south-west, in March and expelled from the party in September. Leftists had been hailing Mr Bo as their champion, a defender of the communist faith. They accused the right of inventing allegations of sleaze in an effort to prevent his rise to the top alongside Mr Xi. The authorities have closed down leftist websites which once poured out articles backing him. But they have not silenced the left entirely: on October 23rd leftists published an open letter to the national legislature, signed by hundreds of people including academics and former officials, expressing support for Mr Bo. The question is, what does Mr Xi think? Will he heed the right’s demands for more rapid political and economic liberalisation, maintain Mr Hu’s ultra-cautious approach, or even take up Mr Bo’s mantle as a champion of the left?

Happy Xiajiang?

There is little doubt that Mr Xi is more confident and outgoing than Mr Hu. His lineage gives him a strong base of support among China’s ruling families. But analysts attempting to divine his views are clutching at straws. A meeting in recent weeks between Mr Xi and Hu Deping, the liberal son of China’s late party chief, Hu Yaobang, raised hopes that he might have a soft spot for reformists. Mr Xi’s record in Zhejiang inspires others to believe that he is on the side of private enterprise (the province is a bastion of it). His late father, some note, had liberal leanings. The Dalai Lama once gave a watch to the elder Mr Xi, who wore it long after the Tibetan leader had fled into exile. This has fuelled speculation that Xi Jinping might be conciliatory to Tibetans. Wishful thinking abounds. The visitor to Mr Xi’s adopted village, Xiajiang, might be encouraged that it has tried a little democracy. A former party chief there says candidates for the post of party secretary have to have the support of 70% of the villagers, including non-party members. During his apprenticeship, however, Mr Xi has been wary of going too far with ballot-box politics. In a little-publicised speech in 2010 he attacked the notion of “choosing people simply on the basis of votes”. That is not a problem he will face at the party congress. from the print edition | Briefing Vaunting the best, fearing the worst Nov 2nd 2012, 16:12

Before the fall of Qing Empire, when Emperor Guangxu was limited by Empress Dowager, Yuan Shi-cai recited a Chinese proverb, “Water falls the lowest seeing one promoting to the ultimate.”, with 3 ambassadors of contemporary power, Britain, France and Japan, drinking a toast to him. He was just a stone a bit larger than dust for Empress Dowager. Ten years on, he monopolized China’s politics but ended soon as smoke.

In China, power is indeed the only truth. By contrast, how to keep power is also a big problem of politics. At a crossroad of history, either continuing economics prosperity or finding a way of reform on politics leads the 18th China’s Communist Party to pass the formidable challenge of ensuring rapid progress in the future.

Time is like an arrow. Last time’s power transition, China accumulated the capital enough to compete with few world’s power in most of fields as 1978-1996 period of 4-timely GDP growth. In 2001, China’s GDP reached 9.59tn yuan, representing an average annual increase 9.3 % before Hu Jing-tao took power over from Jiang Ze-min. And during the following decade, China in Hu’s term enjoyed annual 10.3% high growth. It’s estimated that GDP reach USD 7.56tn in this turning point of this time’s transition. For industrial restructing and European debt, the aftermath of economy in Xi’s term is expected as moderate 7-8% growth.

In post-Deng era, Jiang and Zhu Rong-ji, under the banner of “solidity of the centralization while strengthening technocracy”, ensured the all-directional essential in the process of China’s recovery with Jiang’s warm smile. The modernization of military and politics depended on the liberalized rule and opening mind of both former leaders as serious surveillance everywhere in China. Inside China, Jiang remained stable, especially about the arrangement of officers, and successfully eliminated the voice of dissident, by either armed force or amnesty of diction. Jiang’s image promoted China’s position in the world as “for a more wonderful world” - the compilation of Jiang’s foreign visit - by Zong Zi-chen

In 2003, Hu and Wen Jia-bao succeeded in expectation of democratic approach and rapid economic growth more than ever. In realty, Hu took loosen control of local government, finance, carrying out serious measure of anti-corruption. The fewer interference has China continue growth faster than any other nation; however, the social unrest in Hu’s tenure became more severe than Jiang’s. Although Hu kicked out many corrupt officers such as Chen Liang-yu, the dissatisfaction to government still increased and the thoughts of clear political mechanism prevailed. Besides, the dispute over territory of sea surrounding China became more uncertainty after world war two, including Yellow Sea, East China Sea and South China Sea.

Hu and Wen seems to leave these thorny problems to Xi and Li due to the economic-inclined access to rationality and legitimacy. Always, keeping China’s regime depends on the hierarchy and the efficiency of bureaucracy, rather than democratic or liberalization. That is to say, the political means and control of army still be an indispensable to ensuring the prosperity for some time. Xi accumulates a large scale of “guanxi” (relationship) among China’s politics and business while Li owned the dexterous skill and political grade in local economic promotion with Li’s well-eduacted scholarship in law and economy.

For me, they are very kind of knowing people’s demand and the way of power’s remaining more than Hu and Wen. It’s said that Jiang and Tsang Qing-hong appointed Xi “in a secret room” as Hu’s successor. But the sayings just reflects the truth of Hu’s weaker faction and Jiang’s gorgeous scale. Well, Xi and Li, in expectation of political or economic reform, have the better ability to deal with foreign affairs like financial issue, dispute of territory and with America, Japan and EU. I feel a bit sorry to Hu and Wen, due to their political enforcement poorer than expected - still falling behind developed nation. But I think the situation turns to the better after Xi takes over power. I have high confidence of China’s future 10-yearly exercising policy, based on my experience in Chen Shui-bian’s period. Very soon, the updated information is written in the chapter of national institution in Jiou Hong-chung’s “Constitution”.

As The Economist discussed “the crucial 10-year period for China”, “dialogue” - not just on CCTV - processes both inside and outside China. Every field talks every kind of jargon, leading to new China 2.0. Lets see the most charming Chinese song, during Hu’s term, listening to higher key of Zhou Jie-rong (Jay Zhou) and Fei Yu-qing’s “Beyond A Thousand Miles”

“I see you off - - to the faraway place, with your pale silence. Never for a continued romance may one love muse in that faraway age.

- to world’s end where you’re still now? Hard to hear of sound of keyboard, let alone your sound, I spend all life ever-staying."

Recommended 1 Report Permalink Chinas ruling familiesTorrent of scandalOct 26th 2012, 6:28 by J.M. | BEIJING

AT HIS first news conference as China’s prime minister, Wen Jiabao introduced himself to reporters packed into a cavernous room in the Great Hall of the People (as well as to a live television audience) with an unusual reference to his own family history. Chinese leaders normally hide behind the smokescreen of “collective leadership”, downplaying their own attributes. But Mr Wen waxed lyrical about his own upbringing: “I am a very ordinary person. I come from a family of teachers in the countryside. My grandfather, my father and my mother were all teachers. My childhood was spent in the turmoil of war. Our home was literally burnt down by the flame of war and so was the primary school, which my grandfather built with his own hands. The untold suffering in the days of old China left an indelible imprint on my tender mind.” As a tour de force of investigative reporting by the New York Times now reveals, Mr Wen’s family circumstances have changed a lot since those days. It says that the prime minister’s relatives, including his wife, have controlled assets worth at least $2.7 billion. It notes that Mr Wen has “broad authority” over the major industries where his relatives have made their fortunes. Their business dealings have sometimes been hidden in ways that suggest the relatives are eager to avoid public scrutiny, says the report. That family members of China’s most powerful politicians cash in on their connections comes as no surprise. Over the past two decades, as the country’s economy has ballooned, rumours and occasional bits of evidence of such behaviour have accumulated at a similar pace. In June Bloomberg shed remarkable light on the fortunes of relatives of Xi Jinping, the man who next month will be appointed general secretary of the Communist Party and, in March, president of China. Chinese officials were deeply unhappy with that report: Bloomberg’s entire website has been blocked in China ever since (as has the Analects story about the Bloomberg report). In the few hours since its exposé of Mr Wen’s family appeared, the New York Times’s website has been subjected to the same treatment (ironically, given Mr Wen’s avowed support for “people’s rights to stay informed about, participate in, express views on and oversee government affairs”: see his speech to the National Peoples Congress (NPC), the country’s legislature, in March). Mr Wen and his fellow leaders would prefer any public attention to the business dealings of the powerful to be focused on the family of Bo Xilai, the former party chief of Chongqing region in the south-west. Coincidentally, just after publication of the New York Timesstory, it was announced that Mr Bo had been expelled from the NPC. This was hardly a shock given that he had already been stripped of every other title, including last month his membership of the party. It prepares the way, however, for Mr Bo to be put on trial (NPC membership confers a token immunity from prosecution). This event will likely be staged some time in the next few months and will be the most sensational of its kind involving a deposed Chinese leader since the trial of the “Gang of Four” in 1980. Managing news coverage of it will be a huge challenge to the “collective leadership”. It will want to convince the public that Mr Bo and family members were engaged in egregious corruption (not least in order to block any possibility of a political comeback by the ambitious Mr Bo). But it will not want gossip to spread about the business affairs of other ruling families (squirrelling money abroad appears a national pastime, as we explain in our China section this week). The man all but certain to succeed Mr Wen next March, his deputy, Li Keqiang, will be among those squirming. In a powerful report just published, Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC, has exposed the prominent role of Li Keqiang’s younger brother, Li Keming, in the tobacco industry—even as Li Keqiang has been overseeing reform of the health sector. Airing such conflicts of interest is taboo in the Chinese press. Our cover this week calls Mr Xi “The man who must change China”. Revelations such as those by the New York Times, Bloomberg and Brookings strengthen the case for this. As we argue in a leader, Mr Xi needs to venture deep into political reform, including setting a timetable for the direct election of government leaders as Deng Xiaoping once suggested should be possible. Our Banyan column explains why Chinese-style “meritocracy” is not enough to prevent the kind of abuses of power that are rife in China today. And in a three-page briefing we look at how Mr Xi is being assailed from all sides by demands for far-reaching change. (Picture credit: EPA) « Chinas leadership transition: A troubled inheritance 最後一段所指的當期經濟學者的雜誌封面故事: Xi JinpingThe man who must change ChinaXi Jinping will soon be named as China’s next president. He must be ready to break with the pastOct 27th 2012 | from the print edition

JUST after the 18th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, which starts in Beijing on November 8th, a short line of dark-suited men, and perhaps one woman, will step onto a red carpet in a room in the Great Hall of the People and meet the world’s press. At their head will be Xi Jinping, the newly anointed party chief, who in March will also take over as president of China. Behind him will file the new members of the Politburo Standing Committee, China’s supreme body. The smiles will be wooden, the backs ramrod straight. Yet the stage-management could hardly be more different from the tempestuous uncertainties of actually governing. As ruler of the world’s new economic powerhouse, Mr Xi will follow his recent predecessors in trying to combine economic growth with political stability. Yet this task is proving increasingly difficult. A slowing economy, corruption and myriad social problems are causing growing frustration among China’s people and worry among its officials. In this section · »The man who must change China In coping with these tensions, Mr Xi can continue to clamp down on discontent, or he can start to loosen the party’s control. China’s future will be determined by the answer to this question: does MrXi have the courage and vision to see that assuring his country’s prosperity and stability in the future requires him to break with the past? Who’s Xi? To the rich world, labouring under debt and political dysfunction, Chinese self-doubt might seem incongruous. Deng Xiaoping’s relaunch of economic reforms in 1992 has resulted in two decades of extraordinary growth. In the past ten years under the current leader, Hu Jintao, the economy has quadrupled in size in dollar terms. A new (though rudimentary) social safety net provides 95% of all Chinese with some kind of health coverage, up from just 15% in 2000. Across the world, China is seen as second in status and influence only to America. Until recently, the Chinese were getting richer so fast that most of them had better things to worry about than how they were governed. But today China faces a set of threats that an official journal describes as “interlocked like dog’s teeth” (see article). The poor chafe at inequality, corruption, environmental ruin and land-grabs by officials. The middle class fret about contaminated food and many protect their savings by sending money abroad and signing up for foreign passports (see article). The rich and powerful fight over the economy’s vast wealth. Scholars at a recent government conference summed it up well: China is “unstable at the grass roots, dejected at the middle strata and out of control at the top”. Once, the party could bottle up dissent. But ordinary people today protest in public. They write books on previously taboo subjects (see article) and comment on everything in real time through China’s vibrant new social media. Complaints that would once have remained local are now debated nationwide. If China’s leaders mishandle the discontent, one senior economist warned in a secret report, it could cause “a chain reaction that results in social turmoil or violent revolution”. But, you don’t need to think that China is on the brink of revolution to believe that it must use the next decade to change. The departing prime minister, Wen Jiabao, has more than once called China’s development “unbalanced, unco-ordinated and unsustainable”. Last week Qiushi, the party’s main theoretical journal, called on the government to “press ahead with restructuring of the political system”. Mr Xi portrays himself as a man of the people and the party still says it represents the masses, but it is not the meritocracy that some Western observers claim (see article). Those without connections, are often stuck at the bottom of the pile. Having long since lost ideological legitimacy, and with slower growth sapping its economic legitimacy, the party needs a new claim on the loyalty of China’s citizens. Take a deep breath Mr Xi could start by giving a little more power to China’s people. Rural land, now collectively owned, should be privatised and given to the peasants; the judicial system should offer people an answer to their grievances; the household-registration, or hukou, system should be phased out to allow families of rural migrants access to properly funded health care and education in cities. At the same time, he should start to loosen the party’s grip. China’s cosseted state-owned banks should be exposed to the rigours of competition; financial markets should respond to economic signals, not official controls; a free press would be a vital ally in the battle against corruption. Such a path would be too much for those on the Chinese “left”, who look scornfully at the West and insist on the Communist Party’s claim—its duty, even—to keep the monopoly of power. Even many on the liberal “right”, who call for change, would contemplate nothing more radical than Singapore-style one-party dominance. But Mr Xi should go much further. To restore his citizens’ faith in government, he also needs to venture deep into political reform. That might sound implausible, but in the 1980s no less a man than Deng spoke of China having a directly elected central leadership after 2050—and he cannot have imagined the transformation that his country would go on to enjoy. Zhu Rongji, Mr Wen’s predecessor, said that competitive elections should be extended to higher levels, “the sooner the better”. Although the party has since made political change harder by restricting the growth of civil society, those who think it is impossible could look to Taiwan, which went through something similar, albeit under the anti-Communist Kuomintang. Ultimately, this newspaper hopes, political reform would make the party answerable to the courts and, as the purest expression of this, free political prisoners. It would scrap party-membership requirements for official positions and abolish party committees in ministries. It would curb the power of the propaganda department to impose censorship and scrap the central military commission, which commits the People’s Liberation Army to defend the party, not just the country. No doubt Mr Xi would balk at that. Even so, a great man would be bold. Independent candidates should be encouraged to stand for people’s congresses, the local parliaments that operate at all levels of government, and they should have the freedom to let voters know what they think. A timetable should also be set for directly electing government leaders, starting with townships in the countryside and districts in the cities, perhaps allowing five years for those experiments to settle in, before taking direct elections up to the county level in rural areas, then prefectures and later provinces, leading all the way to competitive elections for national leaders. The Chinese Communist Party has a powerful story to tell. Despite its many faults, it has created wealth and hope that an older generation would have found unimaginable. Bold reform would create a surge of popular goodwill towards the party from ordinary Chinese people. Mr Xi comes at a crucial moment for China, when hardliners still deny the need for political change and insist that the state can put down dissent with force. For everyone else, too, Mr Xi’s choice will weigh heavily. The world has much more to fear from a weak, unstable China than from a strong one. from the print edition | Leaders · Recommended · 12 |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |