字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2019/05/18 21:31:38瀏覽370|回應0|推薦0 | |

2012年11月14日早晨,中共18大選舉出新一代的,學術界稱為第五代集體領導的形成,筆者本來是要回當年11月10日的Treading Water,後來在Leader欄位中,11月15日當週公佈政治局名單,從9人變成了7人。 (未完成) China reveals its new leaders Habemus Papam!Nov 15th 2012, 5:13 by T.P. | BEIJING

WITH ITS UNIQUE and mystifying blend of pageantry, ritual and secrecy, China’s ruling Communist Party Thursday morning revealed the identities of the seven officials it has chosen to lead the nation in the coming years. Ending the tremendous suspense it has generated over the course of a politically tumultuous year, the party made public its newly selected Politburo Standing Committee by sending them striding, in order of seniority, across a red carpet and into the view of journalists and television cameras crowded into Beijing’s Great Hall of the People. Leading the pack was Xi Jinping, 59, the party’s new general secretary. This much was no surprise. Since 2007, Mr Xi has been assiduously groomed and unambiguously tipped for the top job. The selection of the second-ranking figure, Li Keqiang, 57, was also widely expected. But the makeup of the rest of this core group, and even its size, was the focus of intense factional infighting by contenders for top-level power, and the subject of fevered speculation by observers in China and around the world. The other members of the standing committee are Zhang Dejiang, 65, a vice premier who this year also took on the job of Chongqing party boss (replacing the disgraced Bo Xilai, who fell in a spectacular political scandal); Yu Zhengsheng, 67, party boss of Shanghai; Liu Yunshan, 65, director of the party’s propaganda department; Wang Qishan, 64, a vice premier and former mayor of Beijing; and Zhang Gaoli, 65, party chief of the northern port city of Tianjin. All the new members are men. The only woman in contention for a spot, Liu Yandong, was all along considered a dark-horse candidate and did not make the cut. The reduction from nine members to seven was expected, but far from certain until the announcement. The new members are also heavily weighted towards the so-called “elitist” or “princeling” faction of the party. Only two of the seven members, Li Keqiang and Liu Yunshan, are identified with the party’s other main faction, which is seen as having a more populist bent. These designations, however, are somewhat fuzzy and can only be taken as a rough guideline to the real contours of China’s top-level political landscape, and to the question of whether the new leadership tilts more towards conservatives or reformers. Factional lines are drawn not only over policy differences, but also on personal, regional, and patronage networks about which outsiders have only incomplete knowledge. But it does seem clear that Jiang Zemin, who left the top party job a decade ago, has managed to place many of his own protégéson the standing committee, and that the newly departed general secretary, Hu Jintao, came up with the shorter end of the stick. What this new leadership group inherits is a country facing vast and daunting new challenges. Social and economic pressures are growing hand in hand. The global economic slowdown has been matched by declining growth in China. Public sentiment is ever more soured by growing inequality, persistent corruption, environmental degradation, and a sense that the party has lost touch with the lives of ordinary people. In his speech introducing the new leadership, Mr Xi addressed these concerns directly, but with much the same sort of rhetoric the party has been using for years. In one important departure from recent practice, however Mr Xi was also named as head of the party’s powerful central military commission, also on November 15th. In the last leadership transition, Mr Jiang kept things a bit more muddled by waiting two years before relinquishing that job. The announcement of new leaders came a day after the close of the party’s 18th National Congress, at which the outgoing Mr Hu gave his swansong address to the nation (in the form of a stultifying, jargon-laced 64-page speech. This autumn’s change of party leaders will be followed next March by the shifting of government positions. Mr Hu will retain his title as Chinese president until then, when Mr Xi is expected to take it over. At the same time, Li Keqiang is expected to take over from Wen Jiabao as premier. (Picture credit: AFP) Communist Party congressTreading waterPresident Hu Jintao gives his last state-of-the-nation address as China’s leader, admitting the growing contradictions in Chinese societyNov 10th 2012 | BEIJING | from the print edition

SUCH is the secrecy in which China’s Communist Party cloaks itself that Hu Jintao,its leader since 2002, has only twice given a live address to the nation setting out his party’s policies in depth. His second, delivered on November 8th, a week before he steps down, was typically vague. Amid a growing chorus of calls for bolder economic and political reform, both he and incoming leaders favour caution. Intense security in Beijing and to varying degrees across the country on the day he spoke hinted at the party’s nervousness. Despite a decade of breakneck economic growth, discontent is widespread among the less well-off as well as members of a much-expanded middle class, who want more say in how they are governed. Speaking at the opening of a five-yearly, week-long party congress, Mr Hu extolled the party’s achievements since 2002, but repeated what has become a refrain of China’s leaders: that its development is “unbalanced, unco-ordinated and unsustainable”. In this section As a farewell gift to Mr Hu, the more than 2,200 hand-picked congress delegates are expected to amend the party’s constitution to enshrine his appeal for “scientific development” (eco-friendly and balanced) alongside the other theories that supposedly guide the party: those of Marx, Lenin, Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and Mr Hu’s predecessor, Jiang Zemin. There had been speculation before the congress that Mao might be dropped from this list. But Mr Hu paid ritual tribute to the late chairman and his thinking. Party leaders worry about an attempt by a recently purged Politburo member, Bo Xilai, to boost his popularity by appealing to faintly subversive nostalgia for Mao among the poor. But they worry even more that further steps toward “de-Maoification” might prove dangerously divisive within a party already shaken by Mr Bo’s spectacular downfall amid allegations of corruption and a murder cover-up. In his 100-minute address, Mr Hu warned that corruption could cause “the collapse of the party and the fall of the state”. Leaders, however, have often used such language before. And the few specific remedies he offered are also old hat, though the party has made glacial progress in implementing them: more open government, more democracy at the grassroots and inside the party, and greater emphasis on the rule of law. Mr Hu stressed the importance of political reform, but also of continued one-party rule. The man poised to succeed him as party chief and as president next March, Xi Jinping (see next story), was in charge of drafting Mr Hu’s speech. It probably reflected a commonly agreed position that will be hard for Mr Xi to change, barring an economic or political crisis that affects the balance of thinking. In recent weeks articles warning that such a crisis might come in the next decade, and arguing for pre-emptive reform, have appeared even in the official press. People’s Tribune, a fortnightly magazine produced by the party’s mouthpiece, the People’s Daily(and sporting Jiang Zemin’s calligraphy on its cover), published one on the eve of the congress by Yuan Gang of Peking University. It put the warning starkly: “A tightly controlled society in which people only do as they are told, are utterly subservient, and in which there is no freedom of action, will meet a rapid end.” Mr Hu did admit a need for “greater political courage and vision”, and said the party should “lose no time in deepening reform in key sectors”. He repeated calls for “major changes” in the country’s growth model away from reliance on investment and exports towards greater emphasis on consumption. He said market forces should be given “wider scope”, and urged “steady steps” towards making interest rates and the exchange rate more market-driven. But he also spoke of a need to “steadily enhance” the state sector’s ability to “leverage and influence the economy”. Many liberal economists in China have been calling for a loosening of state control over vital sectors, from financial services to energy and telecommunications. Mr Hu said the private sector should enjoy a “level playing field”, but he also said the state should boost its investment in “key fields that comprise the lifeline of the economy”. There is unlikely to be fierce debate over these issues at the congress. When it ends on November 14th delegates will dutifully raise their hands to approve Mr Hu’s report. The tightly scripted choreography of this five-yearly event shows no sign of changing. As usual there will be more candidates than seats available in a new central committee of around 370 people to be “elected” by the delegates. But behind the scenes, party officials will work to make sure the right people are chosen. from the print edition | China · Recommended · 10 筆者的回應: Habemus Papam! Nov 15th 2012, 15:51

The recent focus on China is the reformist figures or dimension in contention. On the surface, there is nothing changed in Communist Party. Some foreign report, like Financial Times, intended to criticize the party lacking of awareness of regime’s unstable while Reuters purposefully reported the reform-inclined Wang Yang and Li Yuan-tsao (very thankful) - Japan’s Asahi Shimbun even posted a photo of Wang Yang as title. Today Xi heads the press conference with the rest 6 members of Politburos core, also succeeded the top leader of Central Military Commission - some to surprise due to the prediction of Hu Jing-tao’s remaining-inclined. Xi’s era comes with no question or quarrel.

Reading Economist’s 10 more posts in Banyan and print edition for 2 weeks, I find out the inclination of Economist, likely to follow David Easton’s theory of political system, has more objective than that of the almost rest. I prefer Gabriel Almond’s theory about structural function, of political role and intra-mechanism. As last week’s video on your mainpage, social unrest, stability and the unbalanced in China are still questioned; meanwhile, China’s foreign policy should remain cautious of neighbor’s hostility along with American military adjustment. Economist referred to the proper way of the oppressed attitude toward opponents as the “compensation” for world’s economic generator, especially facing the cliff of American debt.

Beijing’s mechanism relies on the planned economy on a basis of five-year plan and the supervision of Politburo. Now Politburo stands at the position of exercising propensity; moreover, this generation of party revises some party’s context. With regard to factional politics, princeling party’s Xi holds the 4 seats of Wang Qi-shan, Yu Zheng-sheng and Zhang Gao-li, in contrast of Youth League-factional Li Ke-qiang, while Zhang De-jiang and Liu Yun-shan are few-colourful ones.

The team remains conservative. For website-users in China, Liu’s nominee is a blue-pessimistic outcome while Liu limited free-media too much due to the close affair with Taiwan’s anchorwoman Lu Show-fun (as I know, their relation is hateful and Liu doesn’t like baidu and weibo). The list depends on unique “grade-collection” rule; therefore, after Bo was kicked out, Zhang’s promotion helped Zhang by this rule win over Li Yuan-tsao and Wang Yang reaching the same level of Shanghai and Tianjin’s party chief. Li and Wang, remaining in 25-member Politburo, may be promoted to Vice President, the relative seat in People’s Congress or CPPCC.

By the newly-built structure, Xi’s power is stable rather than Hu’s. Ten years ago, Hu got Zhou Yong-kang’s support gaining national and party’s power with Wen Jia-bao. Hu’s faction wasn’t strong enough to appeal for officers. Xi spent 25 years working in Fujian and Zhejiang before he was in Shanghai and soon became Vice President. During the term in Fujian, Xi released a public letter as the work leader of party’s Taiwan affair, welcoming Taiwan’s group no matter what the background is. Last week, Xinhua reported Xi’s comment on Taiwan concerned, saying his hardening of opinion against Taipei’s remaining “office” in any form - one of Xi’s ambition to exercise China’s politics.

Li Ke-qiang, an English-spoken scholar in law and economics, wasn’t counted by serious definition as Hus faction but Li helped himself owing to professional technique of economics in Henan and Liaoning with good relation with Li Yuan-tsao. Thirteen years ago in Taipei, I first saw his news about the reform on Henan’s AIDS problem as well as a plan to promote economy (the Economist disclosed Wikileak’s information last year, Henan enjoyed annual 15% economic growth in his tenure). Li’s profession costs more than 10-year economic prosperity, also having the ability of many dimensional aspects in State Council about interior and foreign affairs.

Politics indeed runs around while people’s willingness is expressed and officers responsively take on accountability. By contrast, seeing oneself as the tiny when wishing a better tomorrow - especially on the brink of power’s shadow in Asia - just as Ai Otsuka’s song “Jellyfish and meteor”. Either royal or ordinary follows the trend of zero-sum game. With a view to geopolitics, I wrote a very close answer of incoming premiers utmost more than a decade ago. Yes, something is nearly nothing but, sometimes, it looks so bright worthy of a rush for a while.

History, full of occasional random, always praises winner and elite who advance the world. Watching the election of US President in Starbucks near my house, Sino-American relationship remains the same, since Jon Huntsman resigned as Beijing’s ambassador. Like Huntsman, who gave me some help 2 years ago, so many figures walk across the crossroad of Asia-Pacific. In 2005, Hu met Bill Gates and Howard Schutz in Beijing with the great vision of the world. Now multiple environment of world’s economy has Xi be burdened with social unrest.

Recommended 6 Report Permalink 在筆者對經濟學者這篇回應前約一週的相關文章列如下: The National Congress commencesAge before beautyNov 8th 2012, 9:41 by T.P. | BEIJING

THE MONTHS LEADING leading up to today’s opening of the Chinese Communist Party’s 18th National Congress have been filled with uncertainty, anticipation and suspense. Moreover, at November 8th, this year’s Congress arrived at an unusually late date. But the 2,270 delegates who gathered for the meeting in Beijing’s imposing Great Hall of the People were asked to wait just one moment-of-silence longer before getting down to business. This was so that heads might be bowed and respects paid to some dear, departed Communist leaders of the past. These included Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping. Verily, they are gone but not forgotten. The opening session of the Congress highlighted another important fact about elite-level Chinese politics and those past leaders who are still alive and kicking. They have not been forgotten either, and indeed they are not really even gone. Appearing at the dais with the outgoing party chief, Hu Jintao, the incoming chief, Xi Jinping, and other top leaders of the present tense, was an all-star cast of political characters from decades past. To this old baseball fan, it felt a lot like watching Old Timer’s Day at Yankee Stadium. Mr Hu’s predecessor, Jiang Zemin, was there occupying a centre seat of honour. Nearby was a former premier, Zhu Rongji, a former vice-president, Zeng Qinghong, as well as such old heavy hitters as Li Ruihuan, Li Lanqing and Deng Xiaoping’s son, Deng Pufang. Attending also—in a Mao suit—was the 95-year-old Song Ping, a revolutionary leader who left the Politburo Standing Committee in 1992 but spent his Thursday morning following along with the printed text as Mr Hu delivered his swan-song speech. Mr Song would have been hearing very little that was new to his ears. Speaking for more than 90 minutes, Mr Hu laid out a familiar account of the challenges facing China, and of the party’s plans for addressing them. He spoke especially sharply about the danger of corruption, warning that it could cause the collapse of the party and the fall of the state. But this was not new either. It was already old hat more than 12 years ago, when both Mr Jiang and Mr Zhu were prone to spoke in equally apocalyptic terms about corruption. Perhaps to liven things up, Mr Hu added some applause lines about China’s resolute determination to assert its maritime interests. This Congress comes at a time when the country is embroiled in multiple maritime disputes with its neighbours. Meanwhile, with the homage paid to Mao’s cohort and the presence of all those elders, the party’s leaders sought to send two distinct but related messages. The first was that, despite the breathtaking changes that have taken place in Chinese society and economic life, and its sharp turn away from Maoism, collectivism and state-planned orthodoxy, the party wants to be able to assert a degree of continuity with the nation’s founding principles. To do this, Mr Hu’s speech traced a web of convoluted lines that wound back from his own theoretical musings about “Scientific Development” to Mr Jiang’s version of the same (about something called “the Three Represents”; don’t ask). From there the thread runs further back still, through Deng Xiaoping Theory to Mao Zedong Thought, and then all the way to Lenin and Marx. So there you have it: dizzying policy reversals notwithstanding, the party offers consistency, continuity and stability. At a time when political scandals and signs of high-level infighting have been plain for all to see, the presence of the elders was likewise meant to project a sense of unity, continuity and stability. On the surface, it may have done that. But behind the scenes the old-timers appear to be doing as much to stoke the infighting as to cool it, as accounts here and here suggest. If nothing else, their cameos offered a rare chance to see how they’ve been getting on. Mr Zhu stood out for his contrarian reluctance to dye his hair jet-black, as most Chinese politicians do. Mr Jiang looked surprisingly well, considering he suffered a serious health crisis early this year. Discreet sources are saying that he made an excellent recovery and even manages a vigorous swim most days. Thursday he managed to walk on his own, to and from his seat. Standing as other leaders entered the chamber, Mr Jiang cheerfully waved away Mr Hu’s suggestion that he take a seat. Li Peng, best remembered as the hardline premier during the crackdown around Tiananmen Square in 1989, was seated next to Li Ruihuan, and together they seemed far more interested than anyone else in the text of Mr Hu’s speech. Most others followed the remarks as they were delivered (and took part in a traditional, simultaneous turning of pages, which always creates a wonderful swooshing sound in the Great Hall’s cavernous meeting space). But the Messrs Li flipped frontwards and backwards constantly through their copies, leaning down, poring over the text, and looking as if they might have been seeing it for the first time. (Picture credit: AFP) « America-watching: Two countries, two systems Congresses pastRecalling better daysNov 13th 2012, 4:35 by J.M. | BEIJING

THE wooden choreography of the Chinese Communist Party’s 18th congress, now under way in Beijing, strikes Chinese and foreign observers alike as an oddity in a country that in many other ways is changing so fast. The ritual of the week-long event, from the stodgy report delivered by the general secretary on opening day (see our report, here) to the mind-numbing repetition of identical views by the more than 2,200 delegates, has hardly changed in decades. Reuters news agency, whose reporters in Beijing are among the most numerous of any foreign media organisation, said its team in the Stalinesque Great Hall of the People heard no dissent during an entire day of group “discussions” about the state-of-the-nation address presented by the president, Hu Jintao. Journalists can console themselves that things have been worse. In the days of Mao Zedong, party congresses took place in secret, with no news released until they were over. It was not until the 12th congress in 1982 that the party began to arrange press conferences about the proceedings, but it still did not let foreign journalists into the Great Hall of the People. At the 13th congress in 1987 the foreign media were allowed in to watch the opening and closing ceremonies for the first time. Ten years later, at the 15th congress, they were finally allowed to observe some of the delegates’ discussions. These excruciatingly dull events, however, provide almost no useful insights into the party’s workings. As a veteran of Chinese party congresses (having covered one third of them since the party’s founding in 1921) your correspondent delights in the memory of one rare exception to the tedium. It was at the congress in 1987, a year when China was gripped by a struggle between hardliners and reformers in the party. At the end of the congress, after the newly appointed central committee had rubber-stamped the line-up of a new Politburo, journalists waited in a side room of the Great Hall of the People to meet the new leaders. In walked Zhao Ziyang, the just-confirmed general secretary, along with his four colleagues in the Politburo’s standing committee. Zhao looked triumphant. He clasped his hands together above his shoulders in what looked like a gesture of greeting, mixed with one of victory. His reformist faction had come out on top. What followed was the most casual encounter anyone could recall between China’s most powerful men and the foreign media. Separated from them only by narrow tables, Mr Zhao walked slowly in front of the journalists with his fellow leaders, raising glasses with them and appearing relaxed and jovial as he answered unscripted questions; see the photo above. “It is my hope you can send a dispatch saying all my suits are made in China and all of them are very pretty…so as to promote the sale of Chinese garments in international markets,” Mr Zhao said (see this dispatch by the Associated Press). Not exactly side-splitting, but it was remarkable just to hear an attempt at humour by a member of the Politburo. The government’s news agency, Xinhua, engaged in a little openness of its own that day, by revealing Zhao’s age for the first time. It was said he was 68. Many had thought he was 69. Such a freewheeling event has never been repeated. The bloody suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 put an end to any thought of giving foreign media greater access to the leadership. After the next party congress, in 1992, journalists were kept at least a few paces away from the new leaders who walked in to meet them. Jiang Zemin, the general secretary, took only six minutes to introduce his fellow members of the Politburo’s standing committee, before walking out again. No questions were allowed. The format has been the same at all subsequent congresses. Xi Jinping, who will be named the party’s new general secretary on November 15th, is unlikely to try to emulate Zhao’s informality. A congress functionary, asked whether journalists would be allowed to put questions to the new leaders, said simply: “No”. Another high point of the 13th congress that has never been attained at subsequent such meetings was its emphasis on the need for political reform. Mr Hu paid lip-service to the notion in his opening address last week, but most Chinese agree that political liberalisation has been in a virtual deep freeze since Tiananmen. The 13th congress marked the first time that the number of candidates for seats in the central committee exceeded the number of seats. Remarkably a hardliner who was thought to be in line for a seat in the Politburo, Deng Liqun, got so few votes that he failed to make it onto the central committee. This made him ineligible for Politburo membership. In an autobiography published in 2005, Mr Deng accused Zhao (who died that year under house arrest) of trying to persuade delegates to vote against him. Officials are well able to manipulate the outcomes of inner-party elections (see this article in Chinese in Nanfang Chuang, a magazine, describing how it is done at lower-level party congresses). But at the time of the 13th congress, reformists believed that inner-party democracy was on the verge of a breakthrough. Bao Tong, who served as Zhao’s secretary and was imprisoned for seven years for his role in the Tiananmen unrest, says that liberal officials close to Zhao envisaged at the time that subsequent congresses would see competitive elections introduced at increasingly high levels (see our story here). By the time of the 16th congress in 2002 there could be multiple candidates for the post of general secretary, they thought. No such reforms have occurred. Reuters says there could be changes afoot this time, however. If Mr Xi and Mr Hu have their way, the news agency says, there could even be competitive elections for seats in the Politburo. If so this would be a step forward. Mr Bao, however, says the Zhaoists reckoned in 1987 that such elections for the Politburo could be held at the 14th congress in 1992. A quarter-century on, the party is still dithering. (Picture credit: AFP) « Tibetan protest: The living picture of frustration

當天經濟學者雜誌提了一個警語,若中共有黨內人士要作改革,當心光緒皇帝的例子 Parallel historyTimes of intrigue and promiseNov 15th 2012, 8:35 by J.J. | BEIJING

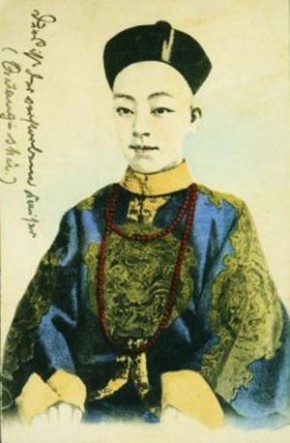

IN THE crisp autumn air of a November day in Beijing, a meeting of notables convened to anoint a new ruler. The previous administration had overseen a decade of reform including new policies that pushed economic and industrial development to unprecedented levels. Sweeping changes in education and growing prosperity, especially in the cities along China’s coastline, transformed society but had also unleashed new social forces that the government struggled to contain. New elites emerged, internationally aware and reform-minded, who began to chafe under the restraints imposed from Beijing and voiced their discontent in new forms of media which—despite its best efforts—the government was never able to fully censor. The date was November 15th, 1908, and the day before Aisin-Gioro Dzai Tiyan, the 37-year-old Guangxu Emperor (pictured above, to the right), whose early experiments as a reforming monarch had led to his spending the last decade of his life under virtual house arrest, had been found dead. His aunt, the Empress Dowager Cixi, the real power behind the throne for nearly half a century, lay dying in the Hall of Mental Cultivation, an ornate pavilion in a small but lush courtyard; she used it as her throne room in the Forbidden City. The notables were Manchu princes of the blood, arch-conservatives concerned as much about their own skins as about the fate of the nation. In less than three years the dynasty they worked so hard to preserve would be gone, swept away by a tide of revolution. It is a popular parlour game among Chinese academics to dig through the past for ways to illuminate the present. An essay posted last year on an influential website, Caixin Online, described the circumstances that led to the fall of the Qing in 1911 in terms that would be starkly familiar to today’s Chinese: corruption, princeling cliques, sclerotic government and “mass incidents”. In case anyone were to miss the point, the author concludes with this fillip: “As then, a large part of the elite now realise the system is ineffective. Finding disturbing parallels 100 years ago only deepens their anxiety. History is not a feel-good business.” Perhaps the most striking parallel is that between the roles played by new media in moulding public opinion. The late 19th century saw the rise of the private newspapers, none perhaps more influential than the Shen Bao, founded in 1872. To start the paper was quite conservative, but in the early 20th century it became an important voice for social and political reform. Shen Baowas the creation of a British businessman, Ernest Major, but it was soon joined by several major Chinese-owned newspapers, all of which provided column-inches to reformers and activists eager to rally support for their causes. They did not have the reach of today’s microblogging services, such as SinaWeibo, but newspapers forged communities of like-minded citizens to organise boycotts against foreign imperialism and to protest the ineptitude and corruption of the increasingly decrepit Qing government. The sudden death of the Guangxu Emperor was mourned throughout China and as far away as the Chinatowns of America. Despite—or perhaps because of—his virtual imprisonment, he had been a symbol of hope for many reform-minded Chinese. His old ally in the aborted reforms of 1898, Kang Youwei, had formed a Society to Protect the Emperor, which advocated a constitutional monarchy with the Guangxu Emperor as the head of state. Many others in China’s new urban elite had been content to bide their time, hoping that the death of the Empress Dowager, then in her 70s, would usher in a new era of change. Any remaining optimism regarding political reform ended that day in November when the Empress Dowager chose a three-year-old, Aisin Gioro Puyi, as the successor to the Guangxu Emperor, and appointed a 13-member cabinet, including Puyi’s father, as his regents. Of the 13 members of the new cabinet, four were Chinese, one was a Mongol and the rest were all Manchu princes of royal blood. A day later, on November 15th, 1908, the Empress Dowager herself died. Revolutionaries such as Sun Yat-sen followed these events closely; as people became disillusioned by the prospects for reform, support for his revolutionary ideas grew. It didn’t hurt that Sun’s biggest competitor for financial support had been Kang Youwei’s Society to Protect the Emperor. Now that the old constitutional monarchist had lost his monarch, support for Kang’s organisation crumbled. Many who once favoured moderation and gradual reforms slowly became radicalised. Revolution went from being a fringe idea to a very real possibility. It might be the understatement of a century to note that there are significant differences between 1908 and 2012. At the time of the Guangxu Emperor’s death, the Qing empire was in the midst of a financial crisis, burdened by excessive indemnity payments to the foreign powers, tariffs fixed by treaty and interest payments on loans to foreign banks. The same foreign powers had divided much of China into “spheres of influence”, keeping large areas of the country under their control through a system of unequal treaties backed by the threat of military force. China today is the world’s second-largest economy and a regional military power. As Peter Perdue, a Qing historian at Yale University and others have pointed out, the Achilles’ heel of autocratic governments—whether imperial dynasties or one-party states—is the question of succession. Certainly, the urban elites of the late Qing took little comfort in being ruled by a series of toddlers. While the process of selection remains as opaque as ever, the Communist Party has made a serious attempt to institutionalise the handover of power. So far as we know, Hu Jintao has not tried to poison Xi Jinping with arsenic-laced dumplings to preserve his grip on power. What has not changed is the importance to the leadership of maintaining the support of an internationally aware and newly prosperous elite, throughout this ongoing November meeting of notables, and beyond. (Picture credit: Wikimedia Commons) « China reveals its new leaders: Habemus Papam! · Recommended · 25 · |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |