字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/07/27 16:22:27瀏覽66|回應0|推薦0 | |

這是第二部份,先貼出筆者在原討論區的回文,接著的第一篇「China and Japan」是9月21日出刊的封面故事。 時隔六年,今天中日之間的紛爭不若當時者慌亂不誕,這一連串的釣魚島(或尖閣群島)糾紛,伴隨著日本和南韓的竹島(或獨島)、和俄羅斯的南千島群島(或庫頁島六外島)領土糾紛,到了數年後,隨著安倍晉三在2012年年底二次上台,半年後安倍首相及其內閣以歷史問題與世代的說明擱置而逐漸平息。 日本官方及執政黨自由民主黨在中日的和與戰態度上,比美國謹慎而由於日本本國安全及利益,朝鮮的核危機和美國一致,又與南韓在各領域上不太好說話。而後在美國特朗普總統上台後,又和美國起了在世界經濟的路線之爭,並且部份地和中國經濟利益上作了讓步。中日的交流在這兩年內的觀光活動與貿易,從三年前的谷底恢復,而日本安倍首相在年內有可能在和中國國家主席習近平會面,雖然有軍事上和鄰國菲律賓、南韓有更密切往來而使中日的安全有疑慮,但可望回到2010年前的熱絡政治氛圍。(2019/05/07補充) 日經新聞網中文版和Stratfor.com是這年至約2017年止,主要的參考來源。經濟學者雜誌一向理性分析各類國際政治事件,筆者特別挑出2012年9月27日,淺談中日之間的歷史恩怨,借古鑑今。 Lame ducks and flying feathers Sep 13th 2012, 07:39

I also feel curious about the purpose of the post by you owing to the different issue from the Economist’s article. Basically, I appreciate your speaking. But, be careful of the belonging of Diaoyu, because Diaoyu cannot be considered - in term of geography - as one part of Ryukyu (Okinawa in Japanese).

By international law and wholly speaking, Ryukyu is Japanese territory after 1874 while Kuomintang Chiang Kai-shek’s “definition” in the recovery of China returning to normal nation (because Chiang was one of strong power in Cairo Meeting) includes Taiwan - as a symbol of “overthrowing” Treaty of Shimonoseki - and excludes Ryukyu - because the Kingdom of Ryukyu (Shang’s dynasty) had the same political position as Li’s Chosen (the empire of Korea) - Ryukyu and Korea were the buffering countries between Japan and China historically.

Take Ryukyu into consideration, and you use some sayings by logic only to feel insensible paradox or say short-circuit. Moreover, if you see Diaoyu as one part of Ryukyu, you recogonize Diaoyu as Japan’s territory and at the beginning you fail to win the argument. Instead, the sovereignty of Diaoyu depends on that of the East China Sea. Ryukyu is classified as farther circumstance which belongs to Japan’s territory. Therefore, “Diaoyu belonging to Ryukyu” is error.

The following is an aggressive diction which is made by China’s next prime minister, Li Ke-qiang, the fourth head talking about Diaoyu in public among China’s Communist Party’s (CCP) Politburo after Hu Jing-tao, Wen Jia-bao and Wu Bang-guo. Hu, Wen and Wu will hand power over to the fifth-generation CCP in a month, so I dont put it in.

On Sep. 11, Li said in Ninxia’s Yinquan that “Diaoyu island and its affiliation is China’s unchanging territory from the ancient time.” “Unarguably, China own its full sovereignty of them.” “China defends national sovereignty and completed territory whose resolution and willingness is unchanged.” “We are due to adamantly protect the sovereignty of Diaoyu.”

“Japan’s position in Diaoyu problem is the public denial of the world’s anti-Facist successful outcome and (moreover) serious challenge of postwar international order.” Li also said.

From Li’s comment, the behaviour of Japan’s prime minister Yoshihiko Noda is nearly equal to that of Taipei authority’s Ma Ying-jeou who is already seen as Adolf Hitler by Taipeis opposition. Well, seemingly, there is some effect after I hand over a report to Li. Owing to the character of such strange kind of both animal, very miserably, the argument may continue for a while.

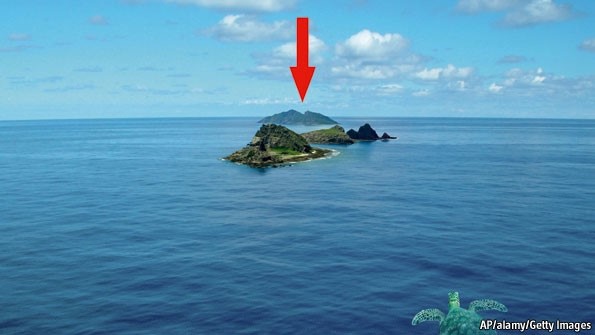

Recommended 5 Report Permalink China and JapanCould Asia really go to war over these?The bickering over islands is a serious threat to the region’s peace and prosperitySep 22nd 2012 | from the print edition

THE countries of Asia do not exactly see the world in a grain of sand, but they have identified grave threats to the national interest in the tiny outcrops and shoals scattered off their coasts. The summer has seen a succession of maritime disputes involving China, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Taiwan and the Philippines. This week there were more anti-Japanese riots in cities across China because of a dispute over a group of uninhabited islands known to the Japanese as the Senkakus and to the Chinese as the Diaoyus. Toyota and Honda closed down their factories. Amid heated rhetoric on both sides, one Chinese newspaper has helpfully suggested skipping the pointless diplomacy and moving straight to the main course by serving up Japan with an atom bomb. That, thank goodness, is grotesque hyperbole: the government in Beijing is belatedly trying to play down the dispute, aware of the economic interests in keeping the peace. Which all sounds very rational, until you consider history—especially the parallel between China’s rise and that of imperial Germany over a century ago. Back then nobody in Europe had an economic interest in conflict; but Germany felt that the world was too slow to accommodate its growing power, and crude, irrational passions like nationalism took hold. China is re-emerging after what it sees as 150 years of humiliation, surrounded by anxious neighbours, many of them allied to America. In that context, disputes about clumps of rock could become as significant as the assassination of an archduke. In this section · »Could Asia really go to war over these? · At last One mountain, two tigers Optimists point out that the latest scuffle is mainly a piece of political theatre—the product of elections in Japan and a leadership transition in China. The Senkakus row has boiled over now because the Japanese government is buying some of the islands from a private Japanese owner. The aim was to keep them out of the mischievous hands of Tokyo’s China-bashing governor, who wanted to buy them himself. China, though, was affronted. It strengthened its own claim and repeatedly sent patrol boats to encroach on Japanese waters. That bolstered the leadership’s image, just before Xi Jinping takes over. More generally, argue the optimists, Asia is too busy making money to have time for making war. China is now Japan’s biggest trading partner. Chinese tourists flock to Tokyo to snap up bags and designer dresses on display in the shop windows on Omotesando. China is not interested in territorial expansion. Anyway, the Chinese government has enough problems at home: why would it look for trouble abroad? Asia does indeed have reasons to keep relations good, and this latest squabble will probably die down, just as others have in the past. But each time an island row flares up, attitudes harden and trust erodes. Two years ago, when Japan arrested the skipper of a Chinese fishing boat for ramming a vessel just off the islands, it detected retaliation when China blocked the sale of rare earths essential to Japanese industry. Growing nationalism in Asia, especially China, aggravates the threat (see article). Whatever the legality of Japan’s claim to the islands, its roots lie in brutal empire-building. The media of all countries play on prejudice that has often been inculcated in schools. Having helped create nationalism and exploited it when it suited them, China’s leaders now face vitriolic criticism if they do not fight their country’s corner. A recent poll suggested that just over half of China’s citizens thought the next few years would see a “military dispute” with Japan. The islands matter, therefore, less because of fishing, oil or gas than as counters in the high-stakes game for Asia’s future. Every incident, however small, risks setting a precedent. Japan, Vietnam and the Philippines fear that if they make concessions, China will sense weakness and prepare the next demand. China fears that if it fails to press its case, America and others will conclude that they are free to scheme against it. Co-operation and deterrence Asia’s inability to deal with the islands raises doubts about how it would cope with a genuine crisis, on the Korean peninsula, say, or across the Strait of Taiwan. China’s growing taste for throwing its weight around feeds deep-seated insecurities about the way it will behave as a dominant power. And the tendency for the slightest tiff to escalate into a full-blown row presents problems for America, which both aims to reassure China that it welcomes its rise, and also uses the threat of military force to guarantee that the Pacific is worthy of the name. Some of the solutions will take a generation. Asian politicians have to start defanging the nationalist serpents they have nursed; honest textbooks would help a lot. For decades to come, China’s rise will be the main focus of American foreign policy. Barack Obama’s “pivot” towards Asia is a useful start in showing America’s commitment to its allies. But China needs reassuring that, rather than seeking to contain it as Britain did 19th-century Germany, America wants a responsible China to realise its potential as a world power. A crudely political WTO complaint will add to Chinese worries (see article). Given the tensions over the islands (and Asia’s irreconcilable versions of history), three immediate safeguards are needed. One is to limit the scope for mishaps to escalate into crises. A collision at sea would be less awkward if a code of conduct set out how vessels should behave and what to do after an accident. Governments would find it easier to work together in emergencies if they routinely worked together in regional bodies. Yet, Asia’s many talking shops lack clout because no country has been ready to cede authority to them. A second safeguard is to rediscover ways to shelve disputes over sovereignty, without prejudice. The incoming President Xi should look at the success of his predecessor, Hu Jintao, who put the “Taiwan issue” to one side. With the Senkakus (which Taiwan also claims), both Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping were happy to leave sovereignty to a later generation to decide. That makes even more sense if the islands’ resources are worth something: even state-owned companies would hesitate to put their oil platforms at risk of a military strike. Once sovereignty claims have been shelved, countries can start to share out the resources—or better still, declare the islands and their waters a marine nature reserve. But not everything can be solved by co-operation, and so the third safeguard is to bolster deterrence. With the Senkakus, America has been unambiguous: although it takes no position on sovereignty, they are administered by Japan and hence fall under its protection. This has enhanced stability, because America will use its diplomatic prestige to stop the dispute escalating and China knows it cannot invade. Mr Obama’s commitment to other Asian islands, however, is unclear. The role of China is even more central. Its leaders insist that its growing power represents no threat to its neighbours. They also claim to understand history. A century ago in Europe, years of peace and globalisation tempted leaders into thinking that they could afford to play with nationalist fires without the risk of conflagration. After this summer, Mr Xi and his neighbours need to grasp how much damage the islands are in fact causing. Asia needs to escape from a descent into corrosive mistrust. What better way for China to show that it is sincere about its peaceful rise than to take the lead? from the print edition | Leaders · Recommended · 14 East Asian rivalryProtesting too muchAnti-Japanese demonstrations run the risk of going off-scriptSep 22nd 2012 | BEIJING | from the print edition

CHINESE authorities have plenty of experience stage-managing nationalistic displays and then suddenly shutting them down. But the latest dispute with Japan—and the ensuing protests in China—has raised tensions to their highest level in years. Japan’s agreement to buy some rocky islands, claimed by both countries, from their private Japanese owner prompted sometimes violent demonstrations in dozens of Chinese cities. On September 14th six unarmed Chinese patrol boats navigated briefly into Japanese-administered waters around the disputed rocks, which Japan calls the Senkaku islands and China calls the Diaoyus. Into this melodrama stepped the American defence secretary, Leon Panetta. He stopped in both countries, urged both sides to get along better and affirmed America’s pledge of mutual defence with Japan—though an unnamed senior American military official stage-whispered to the Washington Postthat America wouldn’t go to war “over a rock”. In this section China, however, has chosen to take the matter of the islands rather more seriously. Xinhua, an official news service, reported that Xi Jinping, China’s vice-president and heir apparent, in his meeting with Mr Panetta on September 19th, called Japan’s planned purchase of the islands a “farce”, urging that Japan “rein in its behaviour”. This kind of rhetoric has become worryingly familiar. China’s actions call to mind similar claims to islands in the South China Sea. (America is officially neutral on claims to all the disputed territory.)

Complicating matters further, China is to undergo a once-a-decade leadership transition later this year. Just now, therefore, no candidates for promotion can risk appearing soft. Mr Panetta’s meeting on September 19th with Mr Xi, who is expected to succeed President Hu Jintao as head of the Communist Party, came just days after Mr Xi reappeared from an unexplained two-week absence that had led to rumours about his health and political standing. It remains unclear whether he will take Mr Hu’s job as chairman of the Central Military Commission, and recent events caused speculation that Mr Hu’s backers, in a push to keep their man on, may have wished for (and even manufactured) a minor crisis. If so, they got their desire. The protests across China climaxed on September 18th, the anniversary of the 1931 “Mukden Incident” that became a pretext for the Japanese invasion of China. Many Japanese factories and businesses shut for the day, and Japanese nationals were advised to keep a low profile. In Bei jing hundreds of Chinese protesters hurled plastic bottles and officially approved abuse at the Japanese embassy. About 50 Chinese protesters inflicted minor damage on the car of America’s ambassador, Gary Locke. Keeping the lid on Then the protests were reined in. While some Chinese boats continued sailing near the islands, Chinese cities returned to normal on September 19th, as suddenly as they had in the largest previous round of anti-Japanese protests in 2005. But holding the Chinese public to a single script is proving more difficult than ever, especially now that citizens (and foreigners—see next page) can write an alternative storyline on Twitter-like microblogs. Some posted their feelings of embarrassment at the thuggish behaviour by some of their countrymen (Japanese cars were a popular target for destruction, and on September 15th a Toyota dealership and Panasonic plant in Qingdao, a port city once occupied by Japan, were reported damaged by fire). Others described efforts by authorities to co-ordinate the demonstrations. A journalist for Caixin, a financial magazine, reported a policeman’s invitation to her to join in a demonstration. When she asked if she could shout anti-corruption slogans as well, he told her to stick to the approved anti-Japanese ones. Anger at Japan is real and enduring in China. Years of Chinese propaganda and patriotic education have deepened the wounds of Japanese wartime depredations. But Chinese citizens also have many other domestic complaints—corruption, pollution, land grabs by officials—that lead to scattered protests around the country every day. Hence, in the short run, stoking anti-Japanese anger can seem a tempting choice for the authorities. Wenfang Tang and Benjamin Darr, two American scholars, concluded in a paper published this month and based on surveys conducted in the past decade, that “nationalism serves as a powerful instrument in impeding public demand for democratic change”. The study also found that China had the highest level of nationalism of 36 countries and regions surveyed. America and Japan were not far behind. from the print edition | China Japan in Chinese historyCross-currentsSep 27th 2012, 11:00 by J.J. | BEIJING

AT A restaurant just up the street from Japan’s embassy on Sunday, September 23rd, local diners were lining up to take advantage of a regular weekend buffet that features tempura, sashimi, sushi and other Japanese delicacies. Just inside the door stood two prominently displayed Chinese national flags. Restaurant staff said business was getting back to normal, but added that it might recover more quickly if both ends of their street were not still blocked off by military-style barricades and police standing watch in full riot gear. The anti-Japanese protests which roiled several Chinese cities last week have subsided, but the situation remains tense. The emotion and vitriol unleashed against Japan during last week’s demonstrations was a reminder that anti-Japanese nationalism remains a potent—and potentially destabilising—force in China. Zhou Enlai once characterised the relationship between the two countries as “2,000 years of friendship and five decades of misfortune”. The latter referring to the period that began with the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895 and lasted to the end of Japan’s occupation of China at the end of the second world war. The history of Japan’s invasion of China, in particular, remains a painful and traumatic memory for many Chinese, including very many who were not yet born at the time. Old wounds from that era are kept fresh through the media, in television dramas and movie plots, as well as in the “patriotic history” curriculum taught in the mainland’s schools. Zhou’s 2,000 years of friendship refers to a long history of cultural cross-pollination. Chinese historians never tire of listing the many contributions China made to the development of Japanese politics, literature, religion and culture. Buddhism represented a key conduit for the exchange of intellectual, philosophical and aesthetic ideas between China and Japan. Even in the bleak years that followed Japan’s humiliating defeat of the Qing empire in 1895—a defeat which resulted in China’s cession of both Taiwan and the chain of islets currently in dispute—thousands of Chinese students went abroad to study in Japan. Their numbers included Chiang Kai-shek, the author Lu Xun, and the female revolutionary martyr Qiu Jin. Sun Yat-sen travelled there many times, organising the Chinese overseas students and recruiting among them for his Revolutionary Alliance. In Japan students learned about medicine, science and the social sciences, and along the way they adopted a new vocabulary to describe the modern world. Literally. Japanese translators used their version of a Chinese Buddhist term sekai (Chinese: shijie), a combination of characters which indicated a distinction in time and space and was used to mean “generation”, and adapted it to mean “the world,” replacing the older Chinese term tianxia, or “all under Heaven”. Last month a programme director for CCTV 1, Xu Wenguang, reminded his microblog followers of the staggering number of Chinese words, especially in the social sciences, which were likewise reimported from Japan. Japanese translators in the 19th and 20th centuries, faced with the daunting challenge posed by concepts like “society”, “philosophy” and “economics”, often simply borrowed classical Chinese phrases, imbuing them with new meaning along the way—creating what Victor Mair, a Sinologist, refers to as “round-trip words”. Centuries after Japanese culture had incorporated Chinese characters as a major component of its own writing system, Chinese students would return from Japan with a new lexicon for scholarship of their own. Nor were the preceding 2,000 years always ones of friendship. In the seventh century, the forces of Tang China clashed with Japanese armies in the Battle of Baekgang. The two-day battle, fought along the Geum river on the Korean peninsula, bore many of the hallmarks that would characterise future conflicts. It began as a proxy war, with China and Japan lining up behind rival powers that were vying for control of the Korean peninsula. This was to be the first of many contests China and Japan would fight in which Korea played the role of a prize. In the 13th century, the armies of Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan empire, carried out a pair of major raids against the Japanese “home islands” (pictured above, courtesy Fukuda Taika). Hopelessly outmatched by the Mongols, the Japanese defenders dug in and prayed. Successfully, as it were, for both times the Mongol fleets suffered enormous damage from sudden storms, divine winds that became known in Japanese as the kamikaze. During the latter years of the Ming empire, the armies of Toyotomi Hideyoshi launched repeated attacks against Korea as part of a grander plan to conquer the mainland. The Koreans called on the Ming court to protect them. The result was a brutal war, featuring the use of early firearms and cannon. The casualties were enormous and the damage proved crippling to both sides—but especially to the Ming empire, which had already begun its final decline. Hideyoshi died in 1598, ending, at least for the moment, visions of a Japanese empire on the mainland. In 1894, China and Japan once again found themselves backing opposed Korean factions and, once again, China—this time in the form of the Qing empire—saw itself acting in defence of a tributary state. Twenty-six years after the Meiji Restoration, Japan was undertaking an aggressive programme to modernise its industry and its army. It was also eager to join the ranks of Europe’s imperialist nations. The Japanese victory dealt a terrible blow to both China’s national pride and to those officials who had worked for decades to modernise China’s own military and industrial bases. It also sparked a crisis of confidence among China’s reformist elite. Never before had the Chinese nation seemed in greater danger of being carved up and divided among the world’s imperial powers. In a web chat posted last week, two of our editors remarked on the similarities between 21st-century Asia and 19th-century Europe. There are parallels there, to be sure, but what is happening today between China and Japan can also be seen as the latest chapter in a centuries-old rivalry between the two pre-eminent powers in North-East Asia. If that history of conflict and violent competition seems to suggest a stormy course ahead in Sino-Japanese relations, an equally deep history of co-operation and cultural exchange must be borne in mind too. It might offer hope that China and Japan can find some way to reconcile their grievances and work together to keep a prosperous peace in the region—even when the newspaper headlines do not. (Picture credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |