字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2019/11/16 01:18:07瀏覽101|回應0|推薦0 | |

(待補)

National People’s Congress Bones and shoals China’s leaders leave the stage. Will their successors be bolder? Mar 9th 2013 | BEIJING |From the print edition · · EVERY year in early March China convenes the annual full session of its legislature, the National People’s Congress (NPC). Despite the important work the body’s increasingly professional full-time staff does during the rest of the year, the annual meetings remain short on drama and long on stage-managed ceremony. The NPC votes on many measures put before it, but has yet to reject a single one. This year’s session, which ends on March 17th, will be more important than most, as it marks the arrival of the people who will run China’s government for the next five years. It began in familiar territory on March 5th with a long speech from the prime minister Wen Jiabao. The speech, marking the end of his ten years under China’s president, Hu Jintao, contained targets for the year: an economic growth rate of 7.5%; an urban unemployment rate of no more than 4.6%; and inflation of 3.5%. Mr Wen also talked of the broader need for reform. The perils of inequality were an important theme. Vested interests with government and party connections dominate many of the country’s most lucrative industries. Mr Wen spoke about tensions in rural areas, too, which are frequently caused by the inability of farmers to assert their property rights and the rampant tendency of local officials to grab land from them. He noted that a guarantee of property rights and the interests of farmers is “central to China’s rural stability”. In this section · Bones and shoals Related topics · China · Politics It will fall to the successors of Mr Hu and Mr Wen to see this through, and it will not be easy. Xi Jinping, who replaced Mr Hu in November as head of the Communist Party and is expected at the end of the NPC session to replace him as the nation’s president, acknowledged as much during a side session with the NPC’s Shanghai delegation. He said China would need to deepen reforms and show more respect for market forces. “We must have courage,” said Mr Xi in a surge of metaphors. “Like gnawing at a hard bone and wading through a dangerous shoal.” Mr Xi, and Mr Wen’s likely successor as prime minister, Li Keqiang, will try to solve their many problems by breaking the grip of party and government officials on the economic life of the nation without threatening the party’s overall control. More will become clear before the Congress ends. But so far, there have been few specifics as to which bones will be gnawed and which shoals waded. · Recommended 11 ·

Bones and shoals Mar 12th 2013, 12:02

This time’s goal of Chinese development by national measurement is relatively easy to achieve. With a view to finance, in one of aspects, entrepreneurs accommodate themselves to take out more loan for further investment.

For example, Samsung, the biggest investor in term of capital inflow into China, may be induced to get more earned income after it already relies on China’s local biggest 4 finance bank. In other term of finance, say, an insurance company Ping An’s big loss of 40% down was predicted owing to the frustration in the process of stake sale between HSBC and Thailand’s Charoen Pokphand Group, with HSBC’s newly-gray record. In addition, China Development Bank played an important role in halting loans to the Thai company as a result of Ping An’s big loss.

In long-term view, basically for the next decade, China’s vision of economic reflects on the urbanization, infrastructure and the intentions of parallel with development, for narrowing the discrepancy and increasing the induce of investment, between western inland and eastern coast. Thus, compared to recent experience of economic advance, restructuring is essential of sustainable growth. Like several Asian nations, especially NIEs, there are examples or problem accumulating seen as China’s cautious plot for reducing redundant annoyance or waste of time and money. Beijing has been carrying out a serious as well as completely integrated policy-planning, from interior to exterior aspect.

Basically, Beijing’s policy mainly depends on the epitome of 5-year plan so there will be less difference between the recent years’ policy by 4th- generation and 5th one in the near time. As a whole, Beijing decrease the target of official work, which inferred lowering demands of economic incitement. It doesn’t mean China would be no road of leading world’s economy. Instead, as Bloomberg and the Economist’s survey, Xi Jin-ping and Li Ke-qiang, who may formally be inaugurated as prime minster, are scheduled to hold the steady annual growth of about 8% in the consecutive 5 years or a bit more. These 3 number of economic growth rate, 7.5%, urban unemployment rate, less than 4.6%, and inflation of 3.5% showed Beijing’s conservative attitude and some soft on the problem of Chinese native enterprises that mostly still lack of international competence. The attitude and soft are known as both China’s market and policymakers, like me, and shown in the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index at the earlier one day before Two-Conferences, including CPPCC and NPC, started setting agendas.

Xi has announced the order of limitation on luxury among top officials and put forward the plan on luxury tax. But both are not the key to the understanding of the indigent or the claim of anti-corruption. I agreed with Murayama Hiro’s comment on Nikkei newspaper last Monday about whether the rich at the top of pyramid pay more tax, although his reason is still questioned. In the process of high growth, the macroeconomics of supply chain may include the expansion of luxury concerned so that some people get benefits of this higher-risky industry. Thus, the expression of notion is better than order. That is, some “right-hand” policy necessarily goes in accordance with the inequality of income. By the way, the forbidden shark fin resulted of the environmental protection better than “anti-luxury” reason.

Besides the public affairs of China’s construction, the second wave of fifth-generation promotion is also focused owing to expanding influence on the world and their characteristic keen to people. And the arrangement of high-rank official reflects the access to the first tenure of Xi’s presidency. Zhou Xiao-chun retained the president of People’s Bank of China for remaining monetary policy. Wang Yang took over the executive vice-premier, supervising the aspect of transport and industry. Yang Jie-chi may follow the step of Tang Jia-xuan, the former minister of foreign affair to be State Councilor while Zhang Yie-xuei, the incumbent China Ambassador in US, gets promotion to vice minister. Yesterday, 67-year-old Yu Zheng-sheng, the former Shanghai’s party secretary, was elected as CPPCC’s chairman after Jia Qing-lin. On Thursday by NPC, Xi will be officially the utmost president in China and, the next day, Li is appointed as prime minister succeeding Wen Jia-bao.

Yeah, I see both my prediction and my advices coming truth, or say winning some prize, that I guessed more than a decade ago. From prediction on the brink to Beijing’s centre work, I hand out some reports to incoming Li, for professional knowledge, so that the policy is easy to practice or I can get some ideas of my shortcomings. Li continues his experiences in Henan and Liaoning of exciting agri-technology plan and trust-oriented economic policy which are integrated into urbanization. Next week, Xi is scheduled to visit Tanzania and Congo, where Wen once had a good chat with local in Chinese language school in 2006.

Recommended 4 Report Permalink

在這組原雜誌貼文和回文,在經濟學者雜誌相關的報導有經濟貿易上的、稅制改革、維穩課題和Banyan評論區展望中國黨政未來數篇: ※經濟貿易上的

Chinas trade FOBbed off Feb 28th 2013, 7:38 by S.C. | HONG KONG · · EARLIER this month we (and a number of others) reported that Chinas trade in goods surpassed Americas in 2012. Americas imports and exports of goods (excluding services) amounted to $3.82 trillion last year, according to the United States Bureau of Commerce. Chinas trade, on the other hand, amounted to $3.87 trillion. For a country that had once embraced communist "self-reliance", this was another striking milestone in its economic transformation. Chinas ministry of commerce, however, felt this mile had been mismeasured. On February 14th, a ministry official told the China Daily, a Chinese newspaper, that his countrys trade still lagged Americas. The United States commerce department, the official explained, "released two sets of figures for U.S. trade last year: $3.82 trillion based on the countrys international balance of payments, and $3.882 trillion based on a measurement similar to that used by the World Trade Organisation." According to the second figure, Americas trade in goods still exceeded Chinas. The officials comments left me befuddled. It is true that America has two different methods of counting trade. The first method, known as the "census" method, counts the goods that cross the border. The second method, called the "balance-of-payments" approach, is subtly different. It counts the goods that pass into and out of foreign hands. But by neither of these methods was Americas goods trade greater than Chinas. The balance-of-payments method valued Americas trade at $3.86 trillion (not $3.82 trillion as the Chinese official said). The census method, on the other hand, valued it at $3.82 trillion. As for the WTO, as far as I understood it, it also counted the goods that cross a countrys border, somewhat similar to Americas "census" method. Its taken me a while, but Ive finally figured out what the official meant. The WTO does indeed count goods that cross the border. But unlike the American "census" method, the WTO typically adds the cost of freight and insurance to the value of a countrys imports. China does the same. Trade experts call this c.i.f (cost of insurance and freight) as opposed to f.o.b (free on board). When you add the cost of freight and insurance to Americas 2012 imports, they increase to $2.33 trillion. And Americas total goods trade (imports plus exports) increases to $3.882 trillion, just as the official said. To find this figure, you have to delve into Exhibit 5 of the Supplement to the December 2012 FT-900 trade report from the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Well go anywhere for the truth. Unfortunately, we dont always get there before deadline. ※金融政策上:周小川先生的去留問題

Monetary policy in China Don’t go Zhou China’s central banker stays put; Chinese central banking moves on Mar 2nd 2013 | HONG KONG |From the print edition · ·

Still on the podium LEAVING the stage is not always easy for Zhou Xiaochuan, governor of China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC). At the Boao Forum (a pow-wow for the powerful) last year, journalists mobbed the platform after he spoke, anxious to catch any titbit that might fall from his lips. One reporter even fell off the stage in her eagerness. Mr Zhou’s exit from the central-banking limelight has also been delayed. After over a decade as governor he recently turned 65, the mandatory retirement age for such posts. When he was squeezed out of the Communist Party’s 205-member central committee in November, his departure from the PBOC seemed imminent. But according to Reuters, a news agency, Mr Zhou will stay put for now. His presumed successor, Xiao Gang, currently the chairman of Bank of China, a state-owned lender, will remain in the background a little longer. Mr Xiao will head the central bank’s party committee, which ensures the PBOC toes the party line, before heading the institution itself. In this section · Don’t go Zhou Related topics · The yuan The delay could be a good sign. Mr Zhou (pictured) is thoughtful, well-known abroad and reform-minded. Nor is 65 particularly old in central-banker years: Alan Greenspan remained at the Federal Reserve until he was almost 80. In other countries, central bankers preside over monetary and financial systems. Mr Zhou has helped to build them. Even before he became central-bank chief, he spearheaded the reform of China’s bond market and the reinvention of its big state-owned banks. In 2005 he also presided over the de-pegging of the yuan from the dollar. If China’s reforms have slowed since then, Mr Zhou is probably not to blame. In China the central bank has no independence and little clout. It does not even decide interest rates, let alone broader questions of currency policy or financial reform. Momentum for reform did pick up in the past year. The exchange rate was given more room to float, curbs on capital flows eased and banks were given greater freedom to set interest rates. If Mr Zhou stays in office, that is a signal the reform drive will continue. But if this is the plan, why will he lose his leadership of the bank’s internal party committee to Mr Xiao? The division of roles can only weaken both men’s authority. One explanation is that Mr Xiao needs a stint on the party committee to learn the ropes. But that does not seem credible. Before becoming head of Bank of China in 2003, Mr Xiao spent over 20 years at the central bank. It is hardly foreign to him. The untidy handover suggests, not support for Mr Zhou, but a lack of consensus about his successor. Perhaps there is still time for the new man to fall off the stage. From the print edition: Finance and economics ※稅制改革

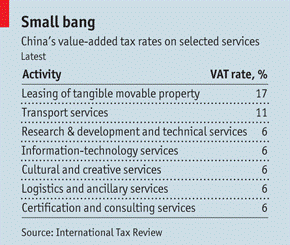

Tax reform A better service game China’s most underrated sector benefits from an undersold tax reform Mar 2nd 2013 | HONG KONG |From the print edition · · IN DEMOCRATIC countries the tax code bends to popular pressures. In China it is more of an instrument of economic engineering. In 2006 the government removed the last of its ancient taxes on agriculture, hoping to narrow the rural-urban divide. Now it is reforming the taxation of services, aiming to boost a sector that creates more jobs, less dirt and almost as much output as industry.

The reform extends China’s value-added tax (VAT) to a variety of services (see table). Shanghai was the first city to take the plunge in January 2012. The scheme has attracted only a fraction of the popular attention paid to the city’s property tax, introduced a year earlier, but it has achieved far more significant results. In this section · A better service game Related topics · Tax law · Law · China Unlike the property tax, which remains confined to Shanghai and Chongqing, the VAT on services has quickly spread to other cities and neighbouring provinces. Lachlan Wolfers of KPMG, an accounting firm, says he expects the reform to expand nationwide by the end of this year. China’s government has long imposed VAT on tangible goods and the tax now contributes a quarter of its revenues. But services are instead subject to the so-called “business tax” (BT). This crude levy is imposed on the value of a firm’s sales. Unfortunately, that value reflects the cost of its inputs, which includes the tax charged by the firm’s suppliers. BT thus obliges service firms to charge a tax on a tax: they must charge it on the taxes already priced in to the supplies they buy. In principle, VAT avoids this cascade. Firms charge the tax on their sales, as before, but when they hand over the proceeds to the taxman, they can claim an “input credit”, deducting the VAT they have themselves paid on their supplies. The tax falls only on the value added at each link in the chain of production. China’s finance ministry boasts that the VAT has so far eased taxes by over 40 billion yuan ($6.4 billion). Small companies have enjoyed an average cut of 40%. In some cities firms can even apply for a partial refund if the test scheme raised their tax burden. But if a lighter tax burden was the ministry’s only aim it could have simply cut BT rates. The true test of the reform is not the revenue it forgoes, but the economic distortions it removes. Unfortunately, the experiment is hampered by its incompleteness. Ever since Deng Xiaoping urged reformers to cross the river by feeling for the stones, policymakers have preferred to start innovations on a small scale. With VAT reform, this made sense. A big bang could have overwhelmed companies, which need to change their invoicing systems, and exposed local governments to unpredictable revenue losses, says Robert Smith of Ernst & Young, an accounting firm. But VAT works best when it encompasses every link in the production chain. China’s small-bang reform is limited to seven services and a dozen localities. Since firms outside the scheme’s scope do not charge VAT, they cannot claim back any of the tax paid on service inputs. The experiment has, in effect, created cross-border transactions within China. And what if a mix of services—some subject to VAT, others to BT—is bundled into a single contract? The loudest complaints have come from transport firms. They used to pay 3% business tax (many others paid 5%). Now they must pay 11% VAT (many others pay just 6%). They cannot deduct the cost of road tolls or insurance, says Teresa Lam of Fung Business Intelligence Centre, a research firm. And they can only deduct the VAT paid on lorries when they buy a new one. A trial limited to certain places was always going to create problems for an industry that carries things from one place to another. When VAT is extended to telecoms—perhaps as soon as July—Mr Wolfers hopes it will apply nationwide. Despite these difficulties, the VAT reform is beginning to bear fruit. The tax’s predecessor encouraged firms to do things in-house to minimise the number of transactions subject to BT. The new tax allows a more natural division of labour. Steel firms are spinning off their transport divisions, according to China’s newspapers, and pharmaceutical firms are creating separate research units. China’s sprawling business groups can now create a single back-office for the entire group. If a company has 50 legal entities in China, it does not need 50 accountancy directors and 50 tax directors. These benefits will encourage the government to expand the scheme further. And the broader the VAT’s scope, the better it will perform.

※中國的高檔汽車市場

Cars in China Still racing ahead China’s luxury car market is a prize—but not for local firms Mar 9th 2013 | SHANGHAI |From the print edition · · MAKERS of luxuries are nervous about China. Its economy has cooled. Worse, its new political leaders are threatening to crack down on ostentation and corruption. What should have been a season of festive political “gift giving” has become a nightmare of rectitude for manufacturers of expensive watches, jewellery and the like. Yet firms that sell fancy cars are as ebullient as ever.

China’s market for such cars has grown 36% a year over the past decade. A new report from McKinsey, a consultancy, calculates that China is now the world’s second-largest market for “premium” cars (which include posh brands like BMW and Aston Martin plus the snazziest offerings from mass-market producers like Volkswagen and GM). It estimates that China will surpass America by 2020 to become the world’s biggest consumer (see chart). In this section · Still racing ahead Related topics · China Would not a crackdown on official cars hamper this growth? In the past it might have. The market for luxury cars was initially fuelled by demand for chauffeur-driven models for officials (black Audis are preferred). Bill Russo of Booz & Company, another consultancy, observes that BMW designed a model just for China with a longer wheelbase, to give back-seat passengers more room; it is so successful that it is now being exported. But even a slowdown in official purchases won’t curb growth much, insists Sha Sha, a co-author of the McKinsey report. Government customers now account for just a tenth of total sales. The surge is due to private demand, including from women and younger drivers. By 2020 China will have 23m affluent households with a disposable income of at least 450,000 yuan ($72,000) a year. Many are in smaller cities ill served by the foreign firms that control this segment. Could that create an opening for Chinese firms? It seems unlikely. Most local cars are produced by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) working in joint ventures with foreign firms like GM and Volkswagen, while some are from private firms like Geely. Another report, from Sanford C. Bernstein, an investment bank, argues that the “SOEs are lumbering, lack entrepreneurial spirit” and rely on foreign technology, while private competitors are “small, lack technology and sell low-priced cars”. Despite decades of trying, China today “cannot build a globally competitive car”, the report bluntly concludes. Chinese drivers do not expect them to succeed soon. Consumers surveyed by McKinsey doubt that Chinese manufacturers will be able to come up with a swooshy car worth buying before 2020. From the print edition: Business

※一胎化政策的檢討 Reforming the one-child policy Monks without a temple China may have begun a long end-game for its one-child policy. Experts say it cannot end soon enough Mar 16th 2013 | SHANGHAI |From the print edition · ·

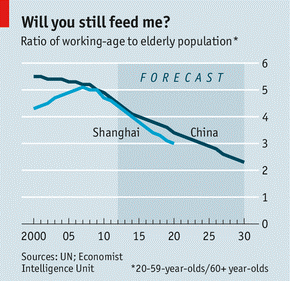

FOR more than three decades the bureaucrats who enforce China’s one-child policy have been among the most ubiquitous, and the most despised, in the country. They are now to lose much of their power, after a government reshuffle announced on March 10th. The question is whether this is the beginning of the end of the one-child policy itself. The news came at a session of the National People’s Congress, the nation’s legislature, which is due to end on March 17th, and was used by the government to announce other ministerial mergers. The Ministry of Railways, which builds and regulates the country’s railways, is being divided, and some of its powers folded into a larger Ministry of Transport. Departments governing food safety and energy are being revamped. A reorganisation promises to bring some of China’s more adventurous maritime agencies under stronger supervision (see article). In this section · Monks without a temple · The old regime and the revolution Related topics · Sexual and reproductive health · Shanghai · China But the most intriguing change is the reorganisation that will merge the family-planning bureaucracy, created purely to control population growth, with the health ministry to form a new Health and Family Planning Commission. Officials have vowed that this does not mean the one-child policy is about to come to an end. But public scrutiny of the policy is growing, along with pressure to loosen or scrap it altogether. Chinese demographers say the social and economic damage done by the policy will be felt for generations. The labour pool is shrinking (by 3.45m in 2012 , the first decline in almost 50 years), the ratio of taxpayers to pensioners will decline from almost five to one to just over two to one by 2030 (see chart), and there are fewer children to support their parents. Shanghai is an example of the demographic time-bomb facing China: its fertility rate, at 0.7, is among the world’s lowest.

Wang Feng, a demographer and director of the Brookings-Tsinghua Center for Public Policy in Beijing, believes that public sentiment will eventually force the end of the policy and that the government’s reshuffle has started the countdown. Up to 500,000 people on the family-planning payroll—the “monks” of the one-child policy, as Mr Wang calls them—have “lost their temple”, he says (a little prematurely). Those who work in the health-care system are much more competent than those in family planning, he adds, so the family planners are more likely to lose their jobs. But this will only happen if politicians decide the policy must go, and so far they have resisted. Some experts say that scrapping it would make little difference in practice. Surveys show that many parents in the cities want only one child anyway. But political leaders still fear that such a reform would result in a sudden burst of population growth, and so far they have held fast, despite the pleas of demographers. “It’s not necessary,” says Zuo Xuejin, of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. “We don’t need the policy any more.” Mr Zuo believes the next step should be to allow all couples to have two children. But that may still be too radical for the leadership. Exceptions are already made for couples anywhere in China where both parents are single children, as well as for people in rural areas whose first child is a girl and for ethnic minorities. In the past two years the family-planning commission wanted to test a new exception for couples of whom only one parent was a single child. It was a conservative proposal, applying to a few provinces and cities, but it still failed to receive top-level approval. Caijing, a magazine, has reported that after the reshuffle this experiment may be tested in areas with low fertility rates. Meanwhile the emerging consequences of the one-child policy are openly discussed in state media. Reports about one social problem—elderly parents whose only child has died—recently featured on national television. Ren Yuan of Fudan University estimates 10m Chinese families have suffered that misfortune, including up to 300,000 in Shanghai. He says the government, having helped create the problem, should bear the burden of managing it. A support group for such childless parents was formed in 2003 at a Shanghai cemetery. Parents there noticed each other at a special section for children, where dolls and other toys adorn the graves. One gravestone is shaped like a desktop computer. The most common concern expressed at their meetings is who will support them as they age. The group registered as an NGO in 2005, but only after overcoming official resistance: bureaucrats were concerned the bereaved families might want to whip up opposition to the one-child policy. Even if they did, they would not be alone. State-run media and microblogs have recently featured reports of a horrific case of forced late-term abortion, leading to public outrage and ever louder calls for an end to the one-child policy. A once unassailable pillar of government control is suddenly looking fragile.

※維穩議題 Urban stability Treating the symptoms In the name of social order, the government turns a blind eye to “black jails” Mar 2nd 2013 | BEIJING |From the print edition · ·

AS A rule, the Majialou Relief and Assistance Centre offers neither relief nor assistance. An imposing complex of red seven-storey buildings, it stands next to an expanse of rubble and a few derelict houses on the south-western fringe of the capital. Few visit unless escorted by police. Few leave except in the custody of officials or their hired thugs. It is a clearing house for Beijing’s undesirables. Majialou and another nearby centre, Jiujingzhuang, are at the hub of a network of extra-judicial detention facilities, authorised by the central government. Their aim is to keep the capital free of “petitioners” who come to Beijing to protest. The city also has many informal detention centres, known as “black jails”, run illegally at the behest of local governments, but to which the central government usually turns a blind eye. The network has been accused of dealing with the symptoms of anger in the provinces rather than its causes. In this section · Treating the symptoms Related topics · China · Beijing Tens of thousands of people arrive in Beijing every year to petition the central government, seeking redress for local injustices ranging from land seizures to police brutality. In the capital they are often detained by police and beaten. Once back in their hometowns some are sent without trial to labour camps as a warning not to try again. Optimists, however, see signs that the central government is waking up to their plight. On February 5th a court in Beijing sentenced ten people to prison terms of up to two years for running a black jail. They had taken a group of petitioners, who had arrived in Beijing last April from the central province of Henan, from Jiujingzhuang relief centre to two black jails on the city’s edge. China Youth News, a Beijing newspaper, reported that some of the protesters were driven back to their hometown a day later. But they soon returned to Beijing where they told the police, who (remarkably) helped secure the release of the others. The sentences were not the first handed down to black jailers. But the unusual publicity the state-owned media gave to the case suggested a new determination by the central government to clamp down on the flourishing business. Even if leaders are intent on a crack down, progress is likely to be slow. Black jails serve the interests of every level of government. Central officials want to keep complainants from coming to the capital and possibly forming a large and dangerous protest movement. The career prospects of lower-level leaders can be ruined by the appearance in Beijing of petitioners from their localities. The relief centres at Majialou and Jiujingzhuang represent progress of sorts. Until ten years ago petitioners were often sent to “custody and repatriation” centres: in effect, jails where they, along with beggars and vagrants, could be held for weeks or even months in harsh conditions before being sent back to their hometowns. These facilities were scrapped in 2003 after an outcry over the beating to death of a university graduate in one of them in the southern city of Guangzhou. But in the capital a new system was set up. Those found petitioning in “sensitive places”, such as Tiananmen Square, would be taken by police to a centre like Majialou where they would await collection by officials from their locality (or, more usually, by toughs recruited by local officials). As soon as a petitioner is admitted to one of the centres, the representative office in Beijing of that person’s home province is notified. In 2010 Beijing News quoted a provincial official saying that these offices are then under central-government orders to arrange for the petitioners to be removed within three hours. Keep the wheels turning Efforts to ensure a rapid turnover encourage provincial officials to use private security companies. These take the petitioners to black jails: usually houses in the suburbs or dingy guesthouses whose owners are paid to keep quiet. The petitioners are held (and sometimes roughed up) there until they can be transported back to their hometowns. In 2010 the Chinese media exposed the case of a private-security company, with 3,000 black-clad employees, that had earned millions of dollars locking up petitioners on behalf of local governments. Another case came to light last year involving a group of black-jail operators that had whisked more than 1,000 people from Jiujingzhuang in 2010 and 2011. A Chinese journalist who has investigated the racket says occasional arrests of black-jailers have had no obvious impact on the lucrative business. Provincial officials continue to deploy private firms or gangs, often to seize petitioners from Beijing’s streets and put them directly in black jails. Some petitioners scornfully refer to the relief centres themselves as black jails. Inside they are separated into different rooms according to their provinces. In Jiujingzhuang, petitioners say, mobile-phone signals are all but blocked. They are watched in their rooms by guards. No beds are provided: they have only hard benches to sleep on. “It is run like a detention centre,” says Zheng Yuming, a petitioner from the city of Tianjin who was taken to Majialou in November. Knowing that real black jails often await them, some petitioners try to resist being taken away. They are usually manhandled out. The authorities show no sign of becoming any less zealous in rounding up protesters. Even if some of those running black jails are being punished, millions of dollars have recently been spent on upgrading and expanding the official centres that supply them with inmates. Government websites say that even before its expansion Majialou was processing an average of about 540 petitioners daily, and that as many as 7,000 people are employed by the facility. Beijing’s media say the centre is now designed to handle as many as 5,000 petitioners a day. It is not clear how often this number will be reached, but a government website said last June that petitioning visits to government offices in Beijing were “increasing dramatically”. Local governments are ill-equipped to cope by themselves, so black jails will remain in strong demand. The heart of the problem is the party’s obsession with weiwen, or “stability maintenance”. In recent years local governments, state-owned enterprises and neighbourhood committees have set up a network of weiwen offices charged with looking out for signs of unrest. Spotting potential petitioners is one of their main tasks. On February 6th Pu Zhiqiang, a prominent Beijing lawyer, used three microblogs to attack China’s recently retired security chief, Zhou Yongkang, accusing him of having “inflicted torment” on the country with his weiwen efforts. Mr Pu’s accounts were soon shut down.

Banyan The old regime and the revolution Why some think China is approaching a political tipping point Mar 16th 2013 |From the print edition · ·

FOR some of China’s more than 500m internet users the big news story of the week has not been the long-scheduled one that their country has a new president, Xi Jinping, who already has more important jobs running the Communist Party and chairing its military commission. Rather it was the unscheduled, unwelcome and unexplained arrival down a river into Shanghai of the putrescent carcasses of thousands of dead pigs, apparently dumped there by farmers upstream. The latest in an endless series of public-health, pollution and corruption scandals, it is hard to think of a more potent (and disgusting) symbol of the view, common among internet users, that, for all its astonishing economic advance, there is something rotten in the state of China, and that change will have to come. Many think it will. According to Andrew Nathan, an American scholar, “the consensus is stronger than at any time since the 1989 Tiananmen crisis that the resilience of the authoritarian regime in…China is approaching its limits.” Mr Nathan, who a decade ago coined the term “authoritarian resilience” to describe the Chinese Communist Party’s ability to adapt and survive, was contributing, in the Journal of Democracy, an American academic quarterly, to a collection of essays with the titillating title: “China at the tipping point?” In this section · The old regime and the revolution Related topics · China Ever since the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, foreigners have been predicting the demise of one-party rule. Surely a political system designed for a centrally planned economy with virtually no private sector cannot indefinitely survive more or less intact in the vibrant, open new China. In 1989 China went to the brink of revolution. When reform came to the Soviet Union and its satellites, for a while China seemed like the next domino, waiting to topple. But the party proved far more durable—and popular—than seemed possible in 1989. And as China’s economy soared and the Western democracies floundered, authoritarianism proved more resilient than ever. With China booming, few tried to emulate the Arab spring of 2011. They were easily dealt with by the pervasive “stability-maintenance” machinery. No single change explains why China might be nearer to a tipping point now. But the evolution of Chinese society is eroding some of the bases of party rule. Fear may be diminishing. Nearly 500m Chinese are under 25 and have no direct memory of the bloody suppression of the Tiananmen protests: the government has done its best to keep them in the dark about it. A few public dissidents still write open letters and court harassment and jail sentences. But millions join in subversive chatter online, mocking the party when not ignoring it. “Mass incidents”—protests and demonstrations—proliferate. Farmers resent land-grabs by greedy local officials. The second generation of workers staffing the world’s workshop in eastern China are more ambitious and less docile than their parents. And the urban middle class is growing fast. Elsewhere, the emergence of this group has brought down authoritarian regimes, through people-power (in South Korea, for example) or negotiation (Taiwan). And much of China’s middle-class seems discontented, furious at the corruption and inequality the party has allowed to flourish, and fed up with poison in their food, asphyxiating filth in their air and dead pigs in their water-supply. The internet and mobile telephony provide tools for spreading news and anger nationally. The party has to work hard to make sure that they do not also help unite all these atomised grievances into a concerted movement. It has a lot of hammers and a lot of nails. But it is still hard to pin jelly to the wall. The other reason for expecting change is that Mr Xi and his colleagues profess to know all this and to be serious about political reform. It has been a recurrent theme at the annual session of the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s Potemkin parliament, under way this week. What looks like a serious purge on conspicuous consumption by freeloading officials suggests the party begins to get it. The “streamlining” of government by merging ministries shows a new willingness to take on powerful vested interests. Mr Xi has urged the party to be brave in tackling reform: “like gnawing at a hard bone and wading through a dangerous shoal” (chewing gum while walking is for wimps). Reform, however, does not mean tampering with one-party rule. Rather, as Fu Ying, spokeswoman for the NPC, put it: political reform is “the self-improvement and development of the socialist system with Chinese characteristics”. Put another way, it is about strengthening party rule, not diluting it. Mr Xi seems to agree. A New York-based website, Beijing Spring, has published extracts of a speech he made on a tour of southern China late last year. He affirmed his belief in “the realisation of Communism”. Democracy in China Mr Xi also spelled out the lesson his party should draw from the failure of its Soviet counterpart: “we have to strengthen the grip of the party on the military.” He is right to pinpoint the willingness or not of the army to shoot people as the crucial difference between the Chinese and Soviet experiences. It is hard to think of a sobriquet Mr Xi would find more insulting than “China’s Gorbachev”. From where he sits, the career of Mikhail Gorbachev is an object lesson in failure. There is a vogue in Chinese intellectual circles for reading Alexis de Tocqueville’s 1856 book on the French Revolution, “The Old Regime and the Revolution”. The argument that most resonates in China is that old regimes fall to revolutions not when they resist change, but when they attempt reform yet dash the raised expectations they have evoked. If de Tocqueville was right, Mr Xi faces an impossible dilemma: to survive, the party needs to reform; but reform itself may be the biggest danger. Perhaps he will see more fundamental political change as the solution. But then pigs will no longer rot in rivers. They will fly. · Recommended 8 ·

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |