字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/06 14:43:08瀏覽7|回應0|推薦0 | |

Unrest in ChinaA dangerous yearEconomic conditions and social media are making protests more common in China—at a delicate time for the country’s rulersJan 28th 2012 | CHENGDU, DONGGUAN AND WUKAN VILLAGE | from the print edition

IN AN industrial zone near Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in south-west China, a sign colourfully proclaims the sprawl of factories to be a “delightful, harmonious and happy district”. Angry steelworkers must have winced as they marched past the slogan in their thousands in early January, demanding higher wages. Their three-day strike was unusually large for an enterprise owned by the central government. But, as China’s economy begins to grow more sedately, more such unrest is looming. China’s state-controlled media kept quiet about the protest that began on January 4th in Qingbaijiang District, a 40-minute drive north-east of Chengdu on an expressway that crosses a patchwork of vegetable fields and bamboo thickets. But news of the strike quickly broke on the internet. Photographs circulated on microblogs of a large crowd of workers from Pangang Group Chengdu Steel and Vanadium being kept away from a slip road to the expressway by a phalanx of police. Word spread that police had tried to disperse the workers with tear gas. In the end, as they tend to—and undoubtedly acting on government orders—factory officials backed down, partially at least. The workers got a raise, albeit a smaller one than they wanted. Managers’ wages were frozen. Related topics Strikes have become increasingly frequent at privately owned factories in recent years, often involving workers demanding higher wages or better conditions. Private firms, like state ones, are usually strong-armed by officials into buying off strikers. The thinking is that capitulating keeps a lid on news coverage and helps to prevent unrest from spreading. Yet the explosive growth in the use of home-grown versions of Twitter has made it easy for protesters to convey instant reports and images to huge audiences. The Communist Party’s capacity to stop ripples of unease from widening is waning—just as economic conditions are making trouble more likely. Anger at the bottom At a cheap restaurant in Qingbaijiang, opposite a dormitory compound for Pangang employees, grimy steelworkers complain that the government’s promise of an extra 260 yuan ($41) a month is hardly enough. Many of the lowest-paid earn as little as $190 monthly. But the workers know that the steel industry is struggling—and that vengeance on persistent troublemakers can be fierce. A police notice warns of legal action, including imprisonment, against any strikers who continue “disrupting public order”. Security agents follow your correspondent in an unmarked car. All this is partly a result of the curb on China’s stimulus spending and carefree (reckless, many would say) bank lending in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008. There are fewer new construction projects; demand for steel has flattened. Pangang’s plant in Qingbaijiang is running at a loss. The number of steel firms in the red rose from nine in September to 25 a month later. Even though the government is less worried about inflation now than it was a few months ago, and is releasing the economic brakes a little, the steel industry is expecting a lean period. Some firms might have to close. Overall economic growth is still looking robust. In the final three months of 2011 China’s economy grew by 8.9% compared with the same period a year earlier—enviable by almost anyone else’s standards, though still the slowest since the second quarter of 2009. The slowdown has so far been gentle, and in line with government efforts to prevent overheating. But this does not stop officials worrying that the coming year could be unusually difficult.

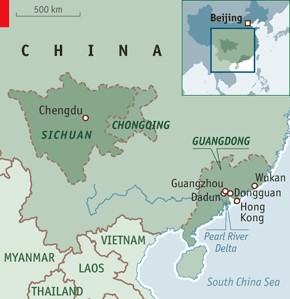

Europe is the biggest buyer of Chinese products—and the euro zone’s travails have plunged many manufacturers into despair. Depressed demand in both Europe and America has taken its toll on factories. The steelworkers’ strike was one of many in recent months, most of them in China’s export-manufacturing heartlands near the coast (see map). Chinese exporters do not face as big a shock now as they did in late 2008, when the financial crisis caused a sudden collapse in demand and the loss of as many as 20m migrant-labour jobs. But that time China’s recovery was rapid, helped by stimulus spending of 4 trillion yuan (more than $630 billion at today’s exchange rate), as well as developed economies’ own stimulus projects. The impact on migrant workers was further mitigated by the coincidence of the worst of the downturn with the lunar new-year holiday, when most migrants go home for lengthy periods. This time exporters face protracted slow growth in developed economies, and the risk that the euro zone’s difficulties might worsen. China’s policymakers do not want another lending spree that might burden the financial system with more bad debt, on top of the borrowing accumulated during the previous binge. The country’s relatively low budget deficit (about 2.5% of GDP in 2010) gives it room to spend more on social housing, social security, tax cuts for small firms and consumer subsidies. These could help promote private consumption—eventually. Nerves at the top The long-term plan is for China to wean itself off its reliance on exports and investment projects such as roads, railways and overpriced property developments, and for domestic consumption of goods and services to play a much bigger role in fuelling growth. But this rebalancing will be a long, hard slog. Officials do not want shock therapy because it could threaten the jobs of many of the 160m migrants who come from the countryside to provide the cheap labour behind China’s exports. This economic quandary has become more acute at what is a delicate political moment for the Communist Party. Later this year (probably in October or November), the party will hold its five-yearly Congress, the 18th since its founding in 1921, at which sweeping changes in the country’s top leadership will begin to unfold. The Congress will “elect” a new 300-member central committee (in fact it will be hand-picked by senior leaders). This will immediately meet to rubber-stamp the appointment of a new Politburo, a body that currently has 25 members. All but two of the Politburo’s nine-member inner circle, the Politburo Standing Committee, will be replaced. Two appointments are all but certain: Vice-president Xi Jinping to take over from President Hu Jintao (as party chief after the Congress and as president next March); and Li Keqiang to replace his boss, the prime minister, Wen Jiabao, also next March. There will be much jockeying for the other slots. It is a decade since China experienced a leadership changeover on this scale—and the first time since the late 1980s that the advent of a new generation of leaders has coincided with such a troubled patch for the economy. The previous time, in 1988, an outbreak of inflation threw Deng Xiaoping’s succession plans into disarray, giving conservatives ammunition with which to attack his liberal protégés. The party’s strife erupted into the open the following year as students demanding greater freedom gathered in Tiananmen Square. The threats to the party today are very different, but fear of large-scale unrest still haunts the leadership. The past decade has seen the emergence of a big middle class—nearly 40% of the urban population, as some Chinese scholars define it—and a huge migration from the countryside into the cities. The party takes no chances. Large numbers of plainclothes police are on permanent watch in and around Tiananmen Square. (Since 2008, visitors to the vast plaza have had to undergo airport-type scanning and searches.) Early last year, when anonymous calls began circulating on the internet for citizens to gather in central Beijing in sympathy with the uprisings that were breaking out in the Arab world, the location specified was not Tiananmen but Wangfujing, a shopping street nearby. The police responded by flooding that area with officers too. In the Pearl River Delta, which produces about a third of China’s exports, there are plenty of signs of malaise. Outside a Taiwanese-owned factory in Dongguan, a dozen or so police officers wearing helmets and carrying clubs watch a small group of angry workers complain that the owner has run away. The factory (which makes massage seats) is unable to pay its debts. They are afraid that, this time, after the lunar new year break they will have no jobs to come back to. A plainclothes policeman tries to silence them. Then a uniformed officer moves in with a video camera, and most of the workers retreat, keeping a prudent silence. Others in the delta have been less reticent. In November thousands of employees at a Taiwanese shoe factory in Dongguan took to the streets in protest against salary cuts and sackings, purportedly caused by declining orders. Protesters overturned cars and clashed with police. Photographs of bloodied workers circulated on the internet. There have been further protests in recent weeks. Guangdong province also saw a wave of strikes in 2010. At that time workers—mainly in factories supplying the car industry—were demanding only higher pay and improved conditions. Most of those disputes were quickly and peacefully settled, and rarely involved action on the streets. The latest spate of confrontations looks different. The steelworkers at the state-owned factory near Chengdu wanted a raise; but, these days, rather than bidding to improve their lots, workers are mostly complaining about wages and jobs being cut. The strikers seem more militant. A report published this month by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) says that, compared with those in 2010, the strikes of 2011 were better organised, more confrontational and more likely to trigger copycat action. “Workers are not willing this time to accept that they have to make sacrifices for the national good because firstly they have already made enough sacrifices, and secondly, fewer are willing to just pack up and go home,” says Geoff Crothall of China Labour Bulletin, an NGO in nearby Hong Kong. Where the heart is The government hopes that jobless migrants will return to their home villages, where they or their families still enjoy a tiny land entitlement on which they can subsist, or find work closer to their hometowns. Many will: job opportunities in the interior have grown in the past few years, thanks to a surge of government investment in central and western areas, aimed at evening out economic growth. Last year Chongqing, a region in south-west China which had long exported large numbers of workers to the coast, for the first time employed more of its surplus rural workforce locally than it sent to other areas. Chongqing’s party chief, Bo Xilai, is believed to be a contender for the Politburo Standing Committee. He has been trying to turn Chongqing into a model for the absorption of rural labour into cities, a project that has involved vast spending on low-cost housing to accommodate the region’s migrants. But rising numbers of migrant workers in big cities—more than 60% according to the National Bureau of Statistics in 2010—are themselves the offspring of migrants and have no experience of agricultural life. They regard themselves as urbanites, even if they are excluded from many of the welfare benefits to which city-dwellers are entitled. They are better educated than their parents’ generation, and more assertive. A riot by migrants last June in Dadun, another factory town in Guangdong where many of the country’s jeans are produced, hinted at the problems China could face if second-generation migrants lose hope. The manhandling of a pregnant woman by security guards prompted two days of violence, with thousands of migrants setting fire to vehicles and government buildings. Strikes in coastal factories now mainly involve second-generation migrants, according to the report by CASS. Such unrest is not about to topple the party. As Chinese officials nervously digest the implications of unrest in the Arab world, demonstrations in Russia and an easing of repression in Myanmar, they draw comfort from the consistency of Chinese opinion polls. These appear to show high levels of trust in the central leadership and of optimism about the future under party rule. Many ordinary Chinese are contemptuous of local authorities, but still believe that leaders in Beijing are benign. The power of weibo But according to Victor Yuan of Horizon, a polling company in Beijing, citizens’ satisfaction with their own lives and confidence in the government, though high, experienced a “big drop” in 2010 and didn’t recover last year. Confidence in the government has fallen by about 10 percentage points, to around 60%.

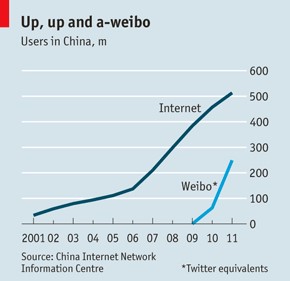

Mr Yuan says the rapid spread of microblogs has contributed to this decline. By the end of last year, weibo, as Chinese versions of Twitter (itself blocked in China) are known, were used by nearly half of the 513m Chinese who had accessed the internet in the previous sixmonths (see chart). This was slightly more than the number who used e-mail and a rise of nearly fourfold over the year before, according to the government-affiliated China Internet Network Information Centre. Li Chunling of CASS estimates that 90% of urban internet users under 30 are microbloggers. Weibohave transformed public discourse in China. News that three or four years ago would have been relatively easy for local officials to suppress, downplay or ignore is now instantly transmitted across the nation. Local protests or scandals to which few would once have paid attention are now avidly discussed by weibousers. The government tries hard, but largely ineffectively, to control this debate by blocking key words and cancelling the accounts of muckraking users. Circumventions are easily found. Since December the government has been rolling out a new rule that people must use their real names to open accounts. So far, users seem undeterred. In the build-up to the 18th Congress, China’s leaders will become especially anxious to prevent embarrassment to the party. Weiboare likely to make their lives a lot more difficult—at least that was the lesson from a ten-day stand-off in December between police and residents of the coastal village of Wukan in Guangdong. The villagers’ protest was typical of thousands that roil the Chinese countryside every year: a complaint about the seizure of agricultural land by local officials for private redevelopment. Unusually, however, in Wukan citizens took control of their village and drove out party hacks and police. Officials were alarmed by images that circulated on weiboof triumphant residents rallying in the centre of their village, like students in Tiananmen Square 22 years ago (see the picture at the start of this piece). They tried, unsuccessfully, to stop news spreading by ordering a block on the village’s name and location. The villagers gave up their protest on December 21st after a rare, high-profile intervention by the Guangdong party leadership, which promised to look into their complaints. Remarkably, on January 15th the protest leader, Lin Zuluan, was appointed as the village’s new party chief (the previous one having disappeared, it is thought into custody). Even the party’s main mouthpiece in Beijing broke its silence on the issue, saying it showed that local officials should stop treating citizens as adversaries. Wang Yang, Guangdong’s party chief, who is believed to be a contender for a senior Politburo position this year, said the incident demonstrated how people’s “democratic consciousness” was getting stronger. He called on officials not to ignore citizens’ concerns. Few regard the Wukan episode as a turning point for the party. At least one protester on Tiananmen Square has since been seen being dragged away by police in the usual fashion. But it has stirred debate, online at least, about how the party should respond to protests and other forms of public pressure. And villagers in Wukan warn that they will not be satisfied until they have reclaimed their land. One protest leader says there could be another, “even bigger” uprising.

Not everyone has a home to go to

The new leadership that will take over after the upcoming Congress will quickly face tests of its ability to handle social unrest. Even if the country does not appear on the brink of an Arab-style upheaval, many Chinese academics say the next few years could see burgeoning instability, exacerbated by slower economic growth and a widening gap between rich and poor. China’s outgoing leaders have tried to suppress debate about ways of reforming the political system to allow the public to voicetheir grievances more freely. But many analysts believe there is a pressing need for such reform. Today’s “China model”, as some in China and abroad were tempted to call it after Western economies fell into disarray three years ago, appears increasingly unsustainable. Chinese roulette An intriguing glimpse of how at least some in the party elite might see things was offered last April when Zhang Musheng, a prominent intellectual, published a book calling for a revival of the one-time Maoist goal of building a “new democracy”. General Liu Yuan, the son of Liu Shaoqi who was China’s president during the Mao era, openly backed the idea. Mr Zhang (himself the son of a late senior official, as are several of the new leaders-to-be) said a new democracy would involve continued party rule but with much greater freedom. Few of China’s liberals believe there is much chance of any leader pursuing this idea in the near future. But Mr Zhang’s description of China today has struck a chord (and has been circulated widely by weibousers). A well-known economist, Wu Jinglian, picked up a phrase of Mr Zhang’s in an essay in Caijing, a Beijing magazine, in which he attacked the notion of a “China model” and called for political reform. The phrase of Mr Zhang’s that made an impression was one describing China as “playing pass the parcel with a time bomb.” from the print edition | Briefing A dangerous year Jan 29th 2012, 17:45

In 2012, Hu Jing-tao and Wen Jia-bao will begin to hand over power to the next-generation Chinese Communist Party (CCP). After two months, In general, these officers, scheduled to start controlling China during the 18th meeting of central committee, have very dexterous abilities to expand the dragon’s big temple and reshuffle the various pedigrees in Chinese inland. Both of faction in the fifth, including princeling party’s Xi Jin-ping and Communist Youth League’s Li Ke-qiang, own their experienced bureaucracy to walk on stage. Also, both have strong network of interaction in each province, seen as support from the senior and younger party members. Furthermore, Xi and Li’s intelligent way to lead and management is indeed enough to qualifies these two as Jiang Ze-min’s successors in 2003-2004. According to Wikileak, these two and the surrounding Wang Yang, Li Yuan-tsaou and Bo Xi-lai have nothing to do with corruption although princeling party was once questioned.

The last change of Beijing’s power occurred in 2003, also seen as the first peaceful transition of Chinese regime from Jiang Ze-min to Hu Jing-tao. Both of Jiang and Hu are appointed or set to sit the seat by Deng Xiao-ping. When the programme nearly finished, coincidentally, the former prime minister Zhao Zi-yang died in his Beijing’s house. At that time, with the full handover of China’s regime, many magazines like TIME posted their predict of Chinese 5-year future and the information which they secretly got or bought. Zhao’s death let this time’s handover impressed. Almost of these editorial referred to Zhao’s death as the requiem of reform, inferring that Hu might take some measures to exercise more democratic policy and announce the anti-separation law (not just for Taiwan).

On average, Hu did fewer than predicted and couldn’t work efficient policy, although Hu put forward the direction, “scientific policy”. In Hu’s tenure, Yangtz River’s construction near Chongqing started helping offering electricity, Hu being the heading engineer due to his profession. In addition, 2008’s Beijing Olympic Game reflected the stronger power of Beijing while Hu smoothly re-elected and watched ping-pong game because he joined ping-pong school team as ping-pong diplomacy flourished in U.S -China. In his second term, Wen rather than Hu showed more in front of the cinema. The main policy was to hold the 8-10% high economic growth. Basically, Hu-Wen system works OK by comparison with the 2000’s circumstance. But the connection, between the senior or the younger and Hu himself, becomes weak when it comes to the handover of Beijing’s regime. So does the connection between the Chinese ordinary and central government. Therefore, many opposite rallies have a chance to protest more and more.

Nowadays, the salary and food price are the critical factor of whether China can keep stable. So do many of other Asian countries’ but less than that of China. Besides, the unstable factor results of Taiwan’s enterprises more apparently due to the employee’s unsatisfied emotion toward the speed of increasing salary. And these kinds of protestors usually tried to mimic Taiwanese including mass rally, offer of their so-called reasonable Renminbi number and the threat to the host of factory or finance concerned. As this Economist’s essay described, almost of serious protest or rally gather in Guangdong, but some of them aim at Taiwanese (for their money) rather than Communist Party (for being an officer). For example, as Li Ke-qiang told me last month, Wang Yang once warned Foxconn’s Guo Tai-min (Terry Guo) because of the worker’s thoughts or the measures. Really, more and more Taiwanese are unwelcomed in Guangdong and the coastal provinces, also bringing the unsteady environment.

As a whole, the fifth generation has more experiences and abilities to avoid the big rally of 1989 Tienanmens kind for their characteristic and policy of good mechanism. Whether this regime can go forward, continuously and steadily is to know the accord or conflict between the two biggest faction (from the top) and to survey what the contemporary people want (from the lowest). By this standard, Xi, who own the massive social network around China among various circles, including entertainment concerned (owing to his wife Pen Li-yuan), and Li, who has the high doctor degree of Peking University and usually exercise logically strategic policy (sometimes viewed as tea table by me), can play the important role in the world in this decade. The rest is to let people know the willingness and clear direction in this tenure so that China is still the generator or propeller of the world beneficially, although Chinese people have some question of Zhao Zi-yang’s concern.

Recommended 43 Report Permalink 在胡錦濤-溫家寶體制的最後一年,政策作解制、開放但又同時要兼顧保安與治安的維穩和社會分配公平,本篇回顧一月內的四川附近的一些罷工場景,如此的街頭抗議與維權,多為爭取勞動權及勞資雙方的對立而來,當年會有民眾公開提出反政府的想法仍然不多。筆者在這時當年有回顧了胡是長江三峽大壩的總工程師出身,是「科學發展觀」具體面最顯著者,後來(本文沒有提)有「開發大東北」的主軸政策,因此有部署栽培李克強升為下一代班底及政治局常委,任上有2008北京奧運的舉辦,一句互動「因為報名時間過了,所以我沒法參加這次的乒乓球項目」,也順勢回顧那代的領導在青少年時期經過的「乒乓外交」的「流行」,胡總也是當年校隊的成員。信奉人民民主的胡在考察時仍不忘馬克斯主義的經濟與勞動聯結,溫家寶的保八有成,是黨的思想驅動,趕得上市場脈動的例證。基本上當年提法紀嚴明即可,政權的穩固大部份來說無庸置疑,不用有太大的軍警調動,倒是很多控管的解制,而市場及民眾的聲音仍然沒有常規管道讓領導較清楚聽到及體會,不免讓人有演進為威權政治的疑慮。在雜誌正文有提到汪洋對於烏崁村事件以開放態度,認為「民主意識」堅強,呼籲不能輕呼市民所關注者。的確今天汪有成功地就任政協主席的位子。「Wang Yang, Guangdong’s party chief, who is believed to be a contender for a senior Politburo position this year, said the incident demonstrated how people’s “democratic consciousness” was getting stronger. He called on officials not to ignore citizens’ concerns.」 後來李克強總理為了鋪政策,即外國俗稱克強經濟學(Likonomics)三大部份而在2015、2016十月都開過企業領導座談會,輔助去槓桿化(整頓影子銀行,初步的金融改革)、不推出刺激政策和重視結構性改革(側重房地產及供給面改革,就城市方面和日本前首相小泉純一郎那套很像)。可市李失敗了,而且習高舉的馬克斯思想大旗,越來越含糊,變成政治性決策壓過任何技術及理性思考,一言堂形成實在令人對中國經濟感到不安。 |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |