字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/04 10:48:49瀏覽29|回應0|推薦0 | |

| 筆者當年回應範圍有這裡有六篇文章內的兩小篇的Special Report 很概括地預測十年內中國黨政經濟及內政外交情勢 筆者特別補充薄熙來應該被剔除的問題

Rising power, anxious state In less than a decade China could be the world’s largest economy. But its continued economic success is under threat from a resurgence of the state and resistance to further reform, says James Miles Jun 23rd 2011 | from the print edition

AT THE HEIGHT of the Qing dynasty, back in the 1700s, China enjoyed a golden age. Barbarians were in awe of the empire and rapacious foreigners had not yet begun hammering at the door. It was a shengshi, an age of prosperity. Now some Chinese nationalists say that, thanks to the Communist Party and its economic prowess, another shengshi has arrived. Last year China became the world’s biggest manufacturer, displacing America from a position it had held for more than a century. In less than a decade it could become the world’s largest economy. Foreigners are again agape. China’s rapid recovery from the global financial crisis, and the West’s continuing malaise, have had a profound psychological impact on many Chinese. Emotions ranging from pride to Schadenfreude permeate official rhetoric. Diplomats treat their Western counterparts with a tinge of condescension. What is great about socialism, crowed the prime minister, Wen Jiabao, in March last year, is that it enables China “to make decisions efficiently, organise effectively and concentrate resources to accomplish large undertakings”. In the eyes of some Chinese, and even some foreigners, authoritarianism has gained a new legitimacy. A big parade of missiles, tanks and goose-stepping soldiers in central Beijing in October 2009, the capital’s first such display in a decade, was described in official reports as a “grand ceremony of the shengshi”. A group of generals and senior officials enlisted 60 artists to commemorate the party’s 60th year in power that year by painting a 120-metre-long scroll called “A Picture of a Chinese Harmonious Shengshi”. The panorama depicted the soaring skylines of China’s great cities, interlaced with the mountains, rivers and clouds beloved of traditional painters. There were ethnic minorities dancing joyously in Tiananmen Square, a rocket taking off, a wind farm and even a mist-wrapped Taiwan. In the past couple of years the shengshi has brought the recalcitrant island closer, with cross-strait flights and a free-trade deal. In this special report < >» Rising power, anxious state « Beware the middle-income trap Where do you live? Deng & Co The long arm of the state Getting on Universalists v exceptionalists Sources and acknowledgments Offer to readers The princelings are coming

Related topics < >Asia-Pacific politics Chinese politics Government and politics World politics To some observers in an insecure West, the balance of global power is shifting inexorably in China’s favour. Recent book titles capture the mood: “In the Jaws of the Dragon: America’s Fate in the Coming Era of Chinese Hegemony” (by Eamonn Fingleton, 2008); “When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order” (by Martin Jacques, 2009); “The Beijing Consensus: How China’s Authoritarian Model Will Dominate the Twenty-First Century” (by Stefan Halper, 2010). As William Kirby of Harvard University notes, anxious books about China’s rise have a long history in the West. There was a spate of them in the early 20th century: “New Forces in Old China: An Unwelcome But Inevitable Awakening”, by Arthur Brown, set the tone in 1904. But other rising powers—Japan, Germany and America—got even more attention. Today China is the chief object of worry.

Chinese publishers have been cashing in too. Bookshops (which stock only works of which the party approves) are stacked with volumes on the “China model” and the failure of liberal economics. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences struck a rare note of modesty in a report last October. It rated China a mere 17th in a global league of “national competitiveness”. But it pointed out that the country had risen from 73rd place in 1990 and had left India, which was ranked 42nd, in the dust. China’s aim, the report said, should be to reach the top five by 2020 and be second only to America by 2050. Its universities are producing swelling legions of scientists, but it seems there are still not enough of them to allow the country to join the top ranks just yet.

For all the chest-thumping, though, China’s leaders are more cautious than either their underlings or the state-controlled publishing industry. They avoid the term “China model” and do not publicly boast of a shengshi, even though they allow their media to talk of one. Indeed, they appear more nervous now than at any time for over a decade. They have massively increased spending on domestic security, which in this year’s budget has overtaken that on defence for the first time. The government has been reviving a Maoist system of neighbourhood surveillance by civilian volunteers. In the past few months the police have launched an all-out assault on civil society, arresting dozens of lawyers, NGO activists, bloggers and even artists. The Arab revolutions have spooked the leadership. From its perspective, the system looks vulnerable. Chinese leaders have other reasons to fret. Late next year, probably in October, the party will hold a national congress, the 18th since its founding 90 years ago. This meeting, a smaller one of the party’s central committee immediately afterwards and a session of the legislature in March 2013 will endorse the biggest shuffle in China’s leadership for a decade. The president, Hu Jintao, and Mr Wen will step down from the pinnacle of power, the nine-member standing committee of the Politburo. A younger generation will begin to take over. Leadership changes on this scale always make officials anxious. Although the most recent one, in 2002, passed without incident, earlier such transitions triggered dramatic events: a coup in 1976, debilitating power struggles in 1986-89 and mass unrest in 1989. Just because the last one went well does not mean this one will.

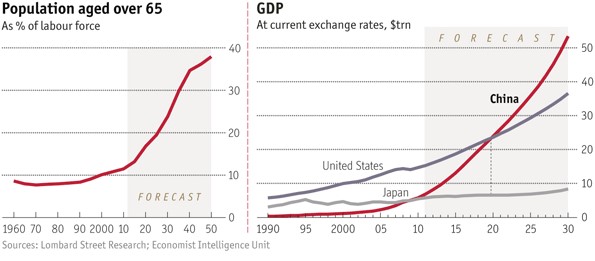

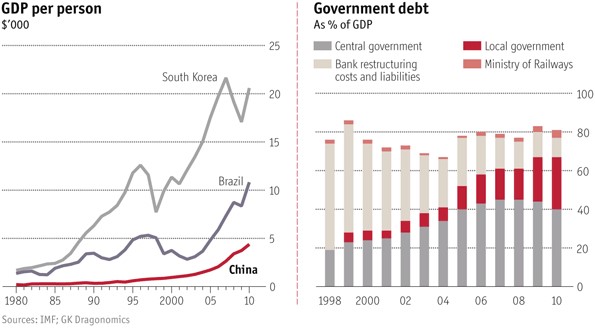

The new leadership will not have such an easy ride with the economy, which on average has grown by over 10% a year since 2002, despite the trauma of the global financial crisis. China’s demographic advantage—an abundant supply of labour in the countryside—is beginning to wane. In a few years the working-age population will peak. Without huge and politically risky policy changes it will become increasingly difficult to maintain the rapid rate of urbanisation that has been one of the main drivers of growth. Looking towards the 2020s, many Chinese economists worry about falling into a “middle-income trap”: losing competitiveness in labour-intensive industries but failing to gain new sources of growth from innovation.

China’s leaders will find it enormously difficult to rebalance China’s economy so that growth is led by consumption rather than by exports and investment. Their efforts will be hampered by the growing clout of state-owned businesses. In the past decade these have risen from the ashes of tens of thousands of government-owned enterprises dismantled in the 1990s. Their numbers are now much smaller, but their economic and political influence is enormous and growing.

Banks are still almost entirely in government hands. Their profligate lending to other parts of the state empire, in order to keep the economy booming after the financial crisis, will revive a bad-debt problem that China thought it had licked years ago. Many of the descendants of those who led the party when it came to power in 1949—the likely big winners in next year’s realignment—have strong ties with state-owned firms. China is likely to disappoint those who believed that the country’s embrace of globalisation would usher in greater political freedoms over the next few years. James Mann, an American journalist, gave warning of this in a 2007 book, “The China Fantasy: Why Capitalism Will Not Bring Democracy to China”, suggesting that a quarter of a century from now China’s “current system of modernised, business-supported repression could well be vastly more established and entrenched”. A lot can happen in 25 years, but the line-up for next year’s change of leadership does not give cause for optimism. Chinas new leaders The princelings are coming Next year’s changes in the leadership will bring on a new generation of privileged political heirs Jun 23rd 2011 | from the print edition

THE RUGGED REMOTENESS of Chongqing, a region in south-western China about the size of Austria, made it an ideal temporary home for the government during the Japanese invasion in the 1930s-40s. In the 1960s Mao Zedong moved strategic industries there to protect them from a feared Soviet invasion. Recently Chongqing has become a stronghold of something rarely seen in China since Mao’s day: charismatic politics. The region’s party chief, Bo Xilai, is campaigning for a place on the Politburo Standing Committee in next year’s leadership shuffle. He looks likely to succeed. Like every other Chinese politician since 1949, he avoids stating his ambitions openly, but his courting of the media and his attempts to woo the public leave no one in any doubt. Mr Bo’s upfront style is a radical departure from the backroom politicking that has long been the hallmark of Communist rule and would seem like a refreshing change, were it not that some of his supporters see him as the Vladimir Putin of China. Mr Bo is a populist with an iron fist. He has waged the biggest crackdown on mafia-style gangs in his country in recent years. He has also been trying to foster a mini-cult of Mao, perhaps in an effort to appeal to those who are disillusioned with China’s cut-throat capitalism. He does not appear to be aiming for the very top. Hu Jintao’s posts of president, party chief and military commander are almost certain to go to Xi Jinping, the vice-president, and Wen Jiabao’s job as prime minister is likely to be taken by Li Keqiang, his senior deputy. But Mr Bo could well be offered the portfolio of China’s internal security chief, currently held by Zhou Yongkang, with whom he is believed to have close ties. This would give him huge clout in the new line-up. Xinhua, a government-run news agency, in December named Chongqing as China’s “happiest” city, in a hint that Mr Bo is destined for great things. In the 1990s the princelings were viewed with great suspicion by many in the party, but recently party leaders appear to have rallied around them In this special report < >Rising power, anxious state Beware the middle-income trap Where do you live? Deng & Co The long arm of the state Getting on Universalists v exceptionalists Sources and acknowledgments Offer to readers » The princelings are coming «

Related topics < >Asia-Pacific politics Chinese politics Government and politics World politics Both Mr Bo and Mr Xi belong to an emerging political force in China commonly known as the taizidang, or “party of princelings”. These are the offspring of senior officials, including Mao’s old comrades-in-arms. Mr Xi is the son of Xi Zhongxun, a hero of the epic Long March of the 1930s. Mr Bo’s father, Bo Yibo, was also a Long Marcher. Both fathers held senior positions under Deng Xiaoping. In the 1990s the princelings were viewed with great suspicion by many in the party who resented their use of blood ties to secure top positions, but in more recent years party leaders appear to have rallied around them. They probably calculate that people like Mr Bo and Mr Xi are the safest bet for upholding the party’s traditions, and crucially for holding on to its monopoly of power.

Mr Xi (who adores Hollywood movies about the second world war, according to a WikiLeaks cable) and the Jaguar-loving Mr Bo exude the sort of self-confidence that comes with a privileged upbringing. Like Western celebrities, they excite much tattle, albeit not in the party-controlled media. Mr Xi’s wife, Peng Liyuan, is a glamorous folk-singing star in the People’s Liberation Army. A foreign businessman calls Mr Bo China’s “best-dressed person”. His son, Bo Guagua, is now studying at Harvard University after a stint at Oxford where his raffish behaviour, caught on camera, became an internet sensation in China (notwithstanding the censors’ best efforts). Despite such diversions, Mr Bo is a darling of China’s “leftists”. These include diehard Maoists (who are a marginal force in Chinese politics, but still enjoy some appeal among retired officials and workers laid off from state-owned enterprises) as well as social democrats who want a fairer distribution of wealth. Many in this camp believe that China is far from enjoying the golden age now being proclaimed by some. The country is too divided between rich and poor to be experiencing a shengshi.

Mr Bo’s Maoist revival has included a campaign to encourage the singing of “red songs”, especially classics from the Mao era (one official newspaper cited Chongqing residents’ enthusiasm for this as one reason for its “happiest” award). Mr Bo himself has taken the stage with fellow officials to croon a few numbers, and has issued a list of 27 favourites (including “I Am a Soldier”, from the early days of Communist rule, and “China, China, the Bright Red Sun Will Never Set”, from 1977, the year after Mao’s death). In Chongqing, party cells in universities, schools, government offices and state-owned businesses organise red-song clubs and competitions. The Chongqing government has even been encouraging citizens to send “red instant messages” on their mobile phones. Mr Bo took the lead by sending one citing the Great Helmsman: “What really counts in the world is conscientiousness, and the Communist Party is most particular about being conscientious.” Tens of thousands of Chongqing officials are now required to spend a week every year living and working with a peasant family.

Chinese leaders may shy away from claiming to have found a “China model”, but Chongqing’s leaders are not so bashful. Piled up in the foyer of the city’s main government-owned bookshop are volumes of a new work called “The Chongqing Model”. Written by three leftist scholars, it reads like a manifesto for Mr Bo. The authors say the anti-mafia campaign will help prevent a “colour revolution” of the kind experienced by numerous former communist states and by some Arab nations in recent years. They speak of the “original sin” of private entrepreneurs who got rich by shady means. The anti-mafia drive, they quote the city’s mayor, Huang Qifan, as saying, helped restore order to “an economy of scoundrels, an economy of rascals”. Mafia-controlled businesses, the writers say, employed 200,000 people. By stepping in and assuming “trusteeship”, the government ensured that none of them lost their jobs. Liberals in Beijing worry that Mr Bo’s campaign has shown little regard for legal process, much less the independence (however notional) of the judicial system. Police and judges have been instructed by party cadres whom to target and what punishments to mete out. A prominent defence lawyer hired by one alleged mafia boss was himself jailed for allegedly attempting to persuade his client to lie in court. Some independent lawyers in Beijing say Mr Bo’s real motive was to deter lawyers from acting for accused gangsters. Liberals fear that the crackdown on dissent in China in recent months will continue even after the princelings have taken power because the new leaders will be fearful of challenges to their authority. The authors of the “The Chongqing Model” would like to steer the economy onto a different path. They speak scornfully of Shenzhen, a freewheeling “special economic zone” bordering on Hong Kong beloved of China’s liberal economists. They prefer a bigger role for the state. Chongqing officials proudly note that the municipality, which ranked 19th among Chinese provinces by value of its state assets in 2003, has since moved up to number four, thanks to a more than sevenfold increase in their worth to 1.25 trillion yuan ($192 billion). But Mr Bo’s predilection for state-owned enterprises has a populist streak too. Whereas most such firms in China hand over little of their profit to the state, causing widespread resentment, officials claim that Chongqing’s state businesses have been supporting projects for the less well off. These include a huge one launched in 2010 to build 800,000 subsidised apartments within three years, at a cost of 120 billion yuan ($18.5 billion). This housing scheme has been widely praised in the national media. But as this special report will argue, if China’s state-owned enterprises enjoy a renaissance under China’s new leaders, it will be to the detriment of competition and increased consumption as a new driver of growth. Politically, their growing power (along with the salaries and benefits enjoyed by their employees) is likely to exacerbate social tensions, especially if China’s growth falters, forcing private companies to scale back. Mr Hu at least will be able to point to a legacy of his decade in power that makes many Chinese proud: double-digit annual growth and a much higher global profile. Mr Xi’s rule could be far more troubled. from the print edition | Special reports ====

The princelings are coming Jun 25th 2011, 17:01

Dear the Economist’s editors: I discretly write this sentences below, having you spend time reading.

I remember the Economist has reported some about the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) fifth generation for several times. From the annual “The World In 2008”, the princiling party’s leader Xi Jin-Ping and the Chinese Communist Youth League’s (CCYL) Li Ke-Qiang were both introduced in preview’s column of China and in the aftermath of 2008 Mar’s Chinese National Congress or the Beijing Olympic’s opening ceremony, Xi Jin-Ping is very sure to succeed President Hu Jing-Tao (reported in Mar. 2008’s Economist). In the circle of China Study(the hottest study of Social Science of the modern world but the most despicable thing in Taiwan) about the core of CCP’s power evolution, the fifth generation is so transparent that you Economist must be incapable of imagining and the biography of these figurehead have been published at least three books in Taipei City since the studious and most famous “thief” Dr. Yang Zhon-Mei (because of owning so many information about their principles and records of office’s tenure) published “The New Red Sun - The fifth generation of CCP”. The cover of Oct. 23 “the next emperor Xi Jin-Ping” is impressed on many readers of the world including me, and the same time, msnbc.com also reported Xi ‘s possible policy and his wife Peng Li-Yuan’s tribute to him by topic “He is the Best”. (In Taiwan, Ya-Chou Magazine once reported this couple in Mar. 2008), or you can see the difference between Xi and Li from Wang Dang’s essay printed in the recent month’s Asian Wall Street Journal (Wang just feels these two not good). I still hold positive attitude toward the Economist because you are not out of date. And in the issue of Apr. 16, the Economist introduced some but still not enough to let reader know how the fifth generation will be working. I have posted one article about the fifth generation on your website on Nov.5, including six figures but not counting Bo Xi-Lai, so I am very, very curious about why you prefer Mr. Bo’s history. I know that Bo Xi-Lai has been working hard and the most succesful officer in the Western Development as we can see on your issue of Mar. 11, 2009. The six people is Xi Jin-Ping, Li Ke-Qiang, Li Yuan-Tsoau, Wang Yang, Liu Ya-Chou and Wang Xi-Hsin, representing party, central government and military sides. Many comments or reply on your Economist.com always show their mistrust of this figures and still think CCP would end itself in the near future. Nevertheless, they are very studious and owning a lot of talent in various techniques enough to hold Beijing’s power steadily. I have been working under Li Ke-Qiang in Taiwan for at least eight years. For this example, I know his charteristic and some “proverb” like “In the way of offical, only by three principles- book, honesty and bureaucracy- can you be a better officer”. Or you can see some bloggers talking about younger officer like Wang Yang. Even you can find some history by just calling some phone numbers or pay attention to some message on cell-phone. As far as I concerned, because I am long-term researcher of Taiwan Issue (and have relations with Hsiao Mei-Qin and Lin Zhon-Bin), I realize these six persons from this point or directly communicate with them through some pipelines. I don’t understand such this big Economist group why you cannot give reader a clearer structure of the fifth CCP’s relation. On the other side, as you talk about Bo Xi-Lai by seeing him as Vladmir Putin of China, I don’t think so (Zhou Yong-Kong who support him can be seen as party’s vice-secretary). According to the more dependable Starfor’s report in 2011/01/01 ”Chinese Provincial Reshuffling and the 6th Generation of Leadership” , indeed, it must have needed for you to focus on these three figures - Hu Chun-Hua, Zhou Qiang and Sun Zheng-Cai - they have already been secretly seen as 2023’s successor rather than Bo Xi-Lai. These three as well as Hu Jing-Tao and Li Ke-Qiang were once the first secretary of CCYL, moreover, one of them along with Li Ke-Qiang and Wang Xi-Hsin have visited Taiwan’s Chen Shui-Bian in 2005’s summer(as I posted on the reply of“the next emperor” on Nov.5) , knowing Taiwan issue and well-prepared for annexing Taiwan island. In other words, it appears that Economist blurred the focus and always steer readers wrong way to know or say misunderstand the fifth generation.

Recommended 41 Report Permalink The princelings are coming Jun 25th 2011, 17:02

(Continued) I have been reading the Economist for about six years. I don’t deny what your editors including the somtimes blunt Banyan do your best letting this magazine be full of various colour and energy. But your recent essays especially this special report, the most obvious weakness is that although you give many information to readers to support the point of view “China will be progressing continuously at least 30 years” , paradoxically, readers only feel pessimistic about Chinese future for you offer some examples such as Ai Wei-Wei. China indeed faces many problem (major in rebalance eastern coast and western inland or city and country), but the factor of protest against Beijing like jasmine revolution is reported too much. Your report lets me think of the CNN senior but stupid correspondent Mike Chiney’s writing style or how to deal with the news. Some also talk about China by scrap of incident and some write articles by way of culture, economy, or figure’s profile as an example. But the key point about nowaday China is these six core people how they were promoted and from this point, you can predict what they will exercise and play an more active role in accompanying with all of Chinese advancing at least ten years. For example, you can know Xi Jin-Ping’s characteristic from his beginning office life of Xiamen’s party secretary in 1986 when I was born, then his princiling party established a kingdom in Chongqing and Southern-east coast in 1990s(many Taiwanese businessman know this pedigree very much and for a long time), and Li Ke-Qiang was elected as the first province governor who owns Doctor Degree, or say Liu Ya-Chou’s acedemic paper about how to win over U.S.A. in Taiwan issue including political and military aggressive competition sides (until now his paper is the main direction of attacking Taiwan), even you can introduce the No.1 land armed force of the Asia in Ninxia ordered by Wang Xi-Hsin(In contrast, Taiwan’s army is “bagayalow” -in Japanese- lacking of prominent commander and must not get any help from foreigners). Li Ke-Qiang, Liu Ya-Chou and Wang Xi-Hsin have had met Taiwan Democratic Progressive Party’s figurehead including Chen Shui-Bian, Lu Show-Lian(Anne Lu), Chang June-Shiung and Hsieh Chun-Ting(Frank Hsieh) in Taiwan. By the way, these three persons work very hard trying to put Taiwan and mainland China together. Many Chinese media including Xinhua and CCTV few reports their history and always let me feel frustrated; furthermore, they choose beautiful scene and rhetoric titles to boost away. The result is to worsen Beijing’s core and make more mistake between central government and Chinese. I saw many people writing this or that in many reply of your articles. Sometimes they show their worries or hate of CCP, but your articles, at the same time, still give readers the variety of obversative numbers. Concluding these six figureheads how to work after they get power in 2012-2013, I give a metaphor that the Japanese famous singer Kana Nishino’s “distance” can reflect on their eagerness - they indeed cannot wait for the turnover of power and want to surpass the past “ Great Ching dynasty’s shengshi”. As far as I concerned, they own many blueprint building more gorgeous Xanadu and actively continue the political reform. Thanks for your reading so patiently.

Recommended 42 Report Permalink 這是筆者當年對專題報導的回文分兩篇,因5000字母限制分貼出來。這篇刊出太子黨的兩大人物,除了習近平之外還有薄熙來的蒸蒸日上。筆者抱著一個求真查證的精神回過這本的編輯,希望經濟學人不要學紐約時報、CNN及TIME雜誌非常捧薄熙來並稱作是中國民主化的惟一希望,果真如此,會忘了當年胡錦濤的團派子弟在2005年5月連胡會後曾經派李克強等人來台過施壓。李曾率了當年被視為第六代集體領導胡春華及周強來台探望陳水扁前總統,並在台北賓館設宴款待。現任最高人民法院的院長周強甚至在2006年曾經訪問過湖南省的大陸新娘眷屬,除了台東的泰源附近,就是我阿姨中的潭子那戶啦。筆者過幾年後在薄出事後,曾問過這三四位及解放軍將領劉亞洲,其實薄熙來不怎麼樣,當年靠馬向東案竄上來的,而且算起來曾經是抓法輪功學員的第一大將,在大連被羅織罪名的人數居全國最多。怎麼被西方媒體捧成這麼高還陪薄玩星海爭霸,顯然有邏輯上錯誤。當時筆者被內地官員囑付那薄是特立獨行過來的,像級了美國某諧星,不是搞政治的料,不要去跟著哈一時的爽,果然兩三年後出事,噓聲沒有白出,別講筆者恨民主政治啊~ 另一方面,提到了太子黨之外的團派的可能升遷人物,有汪洋和雙重淵源的李源潮,這裡引用楊中美博士按照功績預測的名單,除了習和李:分別有李源潮、汪洋、兩名將領是也來過台灣見過時任民進黨主席的張俊雄的劉亞洲和王西欣,大致上是太子黨氣勢凌駕於共青團派,而當時政治局24-25人席次上預測第五代2013年接胡錦濤的棒後,團派仍多於太子黨。希望經濟學人也有專題報導。他們和台灣的相聯度比前一代胡溫體制高。王丹當年曾經覺得習和李都不怎麼樣,由於他們比較沒有遇過大風大浪,但這方面而言也有說服力不夠。這些現在是五六十歲的大員,他們頭腦和之前共黨執政者相比較為現代化,可是基於中國的政治及社會多元化發展,需要有一點膽勢歷練者,而非憂柔寡斷者。不過相較之下,筆者當時還是希望是有學識的人出頭,習是在長輩派系間夾縫中過來的人,本來江澤民拉拔習,欲以壓制共青團和偏陳雲的老一代現在八九十歲的一般官員及紅二代,甚至還有曾慶紅的密室造王說,倒是江忘了自己在提拔其他方面,如從縣級到省級與國營事業主管時也或多或少還是要以公平開放甄選,不免還是有小派系或地方派系上台,現在有的還在挺習,有的反的很嚴重。後來對江而言變成禍害,常常被查是否貪贓枉法,在今年三月中國憲法經中共修憲後,因習的擴權而有了更極權的政府,本來習這個是江拿來調節派系的人選,今日聽來不勝欷噓。 這段引用的第二段刻意作人物側寫,除了習近平外就是薄熙來和他的夫人彭麗媛,當年在描述起來好像看查士丁尼大帝,和他的皇后及大將貝利沙留。不過事實並不是,薄熙來榔鐺入獄後或以保外就醫了,而兒子薄瓜瓜則在紐約作執業律師。看這篇時有回憶起2008年的亞洲週刊的專題報導習近平夫婦的故事。而筆者在其後經濟學者雜誌的報導也有附註這位山東出生的苗族第一夫人的親姑姑,目前仍然在台灣嘉義居住。這盛世仍在習近平的「中國夢」中追尋著,有太多社會和經濟上的轉型和結構改革要作,力猶未迨。(2018,08,04補充)

之後在討論區的篇幅改用連續打字,改了排版方式而非以換行為主,筆者之後統一以EI Office 2007或Microsoft Word 2007&2013及之後Office 365 Word排版。段與段之間要留一行再貼上去。(2018,08,04補充) |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |