搜尋大溫中式英語 惹爭議

世界日報江先聲∕特稿

May 12, 2010

「溫哥華太陽報」專欄作家陶德為了透過語言探討華人移民如何在文化上作出調適,徵求讀者提供本地中式英語(Chinglish)的例子,不料被抨擊有種族歧視之嫌,又或是肆意嘲笑人家的英語水準。

陶德以敢於突破禁忌探討宗教、倫理、以至性愛等問題,而在新聞報導和評論方面屢屢獲獎。他這次看來也是兼持一貫的中立態度探討問題。

從語言學來說,中式英語,或洋涇濱英語(Chinese pidgin English),或其他洋涇濱語言(pidgin language)或混合語(creole language),都是正當的語言學研究課題。甚至有語言學家對這些混雜語言給予正面評價,認為把兩種不同系統的語言混雜使用,是具創造性的語言行為。

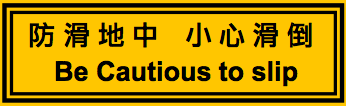

可惜,陶德拋磚引玉所舉的例子,都不是語言學上正當的中式英語例子。譬如他列舉中國大陸等地一些告示牌上的例子,像把「小心滑倒」譯作「Be cautious to slip.」(要小心地滑倒)等等。

這些常被引作笑柄的例子,都是英語水平欠佳而犯了錯誤的破英語,不是中式英語。

所謂中式英語,是指把中文的語法或其他語言結構挪用於英語。最經典的例子,就是把「好久沒見」譯作「Long time no see」。中文的一般語法結構比英語簡單,譬如沒有詞尾,沒有時態,沒有冠詞(a、the等),介系詞(preposition)等也簡單得多,因此便有此簡單的直譯(正確譯法應為Haven't seen [you] in a long time)。

這句經典的中式英語甚至進入了英語,成為可接受的英語句子,有人更認為這種簡潔的說法很不錯。

大溫地區可見的中式英語大抵只是零星現象,但同樣可見證文化的交融與調適,值得研究,但出發點必先認清什麼是中式英語,否則便很容易流為網上充斥的笑話,只是取笑一下人家英語如何不濟而已。

洋人常一頭霧水

陶德所舉的把「小心滑倒」誤譯作「Be cautious to slip」的例子其實來自維基百科;類似例子多不勝數,也有譯作「Slip carefully」(小心地滑落);但這都不是真正「中式英語」的例子。 (網路照片)slideshow 中式英文(Chinglish)一般是含有中國文化的英文,華人看了會心一笑,但總能瞭解其中意涵,洋人則可能會一頭霧水。

「溫哥華太陽報」專欄作家陶德(Douglas Todd)撰文指出,洋人會在濕滑地面前放警示牌,寫「Wet Floor(地面潮濕)」;中國人是提醒「小心滑倒」,但直接把中文翻成英文就成了「Be Cautious To Slip(要小心地滑倒)」。

溫哥華比較不容易見到這麼道地的中式英文,但是中式英文不只是這些讓人莞爾的錯誤翻譯。許多華人對於某些文字的感受,與洋人有極大的差異,為了適應這種差異,華人齊聚的大溫地區產生另一種中式英文。例如憂鬱(depression)和治療(therapy)在洋人眼中沒什麼不妥,但在大溫的華人圈中就不受歡迎。

Chinglish in Metro Vancouver

By Douglas Todd

Vancouver Sun, May 10, 2010

Instead of a yellow sign warning people about a "wet floor," the Chinglish sign says, “Execution in progress" or "Be cautious to slip."

Instead of "Keep off the grass," the Chinglish sign anthropomorphizes nature and says: "The little grass is sleeping. Please don’t disturb it.”

Instead of “No swimming,” the Beijing sign advises, “Keep off the lake.”

A New York Times' writer and other journalists, including Canwest's ace Aileen McCabe, have recently been telling Canadians about the charming and amusing derivations of English they are seeing in China these days.

But are there also examples of Chinglish in Metro Vancouver, where roughly one-fifth of the population is ethnic Chinese and many are still learning the intricacies of English? (And they are doing far better than I, by the way, at learning Chinese, let alone French. The quest to learn a second language takes enormous determination and brainpower, both of which, when it comes to languages, I seem to lack.)

I'm calling on readers to send in examples of how Canadian people of ethnic Chinese origin are adapting English aphorisms and words in the name of cultural integration.

I first ran into what might be considered a form of Chinglish in Richmond in 2008 when I researched an innovative program for depressed Chinese people run out of Richmond Hospital.

As Richmond Mental Health psychologists and counsellors created the program, they realized Chinese patients rejected certain words, including "depression" and "therapy" because they had a cultural stigma.

For instance, instead of using the word "depression," the creators of the program began talking about "sadness," which is more socially acceptable in Chinese culture.

Here is an excerpt from the article of Feb. 23, 2008, headlined Deep, Deep Sadness:

Given such strong Chinese resistance to Western therapy, which tends to highlight freedom and self-realization, the Richmond team had to come up with novel ways to draw in people from the more hierarchical, collective culture.

The Richmond team experimented with changing Western psychological language as part of their study, which was published in the prestigious American scholarly journal, Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training.

They appealed to Chinese-Canadians' willingness to engage in hard work and self-criticism, for instance, by giving their treatment program an earnest-sounding title

Even though the team was dealing with Chinese-Canadians who struggle with what North Americans call "depression," the researchers instead creatively called their program "A Course on Diligent Practice of New Thought."

They came up with the unusual name for the therapy program, says psychologist Edward Shen, because "Chinese people like to take courses" -- especially those aimed at self-improvement for the sake of the group.

"They're very motivated to seek help, but not therapy," he said.

Throughout the treatment, the Richmond Hospital therapists tried to sidestep the word "depression." The term, Shen says, mainly makes sense to North Americans (and not even to many Europeans).

Even though many of the Richmond Hospital patients were taking anti-depressant medication and suffering from the severe emptiness, hopelessness and suicidal thoughts associated with depression, the therapists wanted to avoid the word because it might suggest mental illness.

The researchers instead emphasized their program was for people dealing with "sadness," which is a more accepted state of mind in Chinese culture.

The team's efforts to treat their clients' severe distress, however, was complicated by the way Chinese culture teaches feeling "sad" is acceptable.

"The Chinese way of thinking tends to be more pessimistic relative to the West," says Shen. "We very readily accept sadness as part of life, where 'depression' is not accepted."

Many Chinese people believe sadness simply comes from accepting one's "fate," one's lot in life, Shen said.

字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大