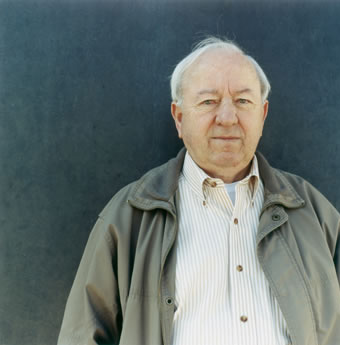

Bud Welch的愛女,在1995年美國奧克拉荷馬大樓爆炸案中不幸喪生,他傷心欲絕終日沉溺在酒精企圖麻痺自己,後來卻決定站出來為爆炸案主嫌Tim McVeigh奔走求情,希望不要判處死刑。

聽起來很不可思議吧!他們並沒有崇高的宗教情操或偉大的悲天憫人胸懷。Bud Welch只是淡淡地說:「我必須做些不同的事情,因為過去我所作的並沒有用」。(I had to do something different, because what I was doing wasn't working.)

奧克拉荷馬市政府大樓爆炸案發生六個月後,民意調查顯示85%的受難者家屬希望主嫌Tim McVeigh被判處死刑;六年後數字掉了一半;現在絕大多數的受難者家屬認為,當初判處死刑是錯誤的決定,因為即使把主嫌處死他們並沒有覺得比較好過。

以下是Bud Welch的故事...

In April 1995, Bud Welch’s 23-year-old daughter, Julie Marie, was killed in the bombing of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. In the months after her death, Bud changed from supporting the death penalty for Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols to taking a public stand against it. In 2001 Timothy McVeigh was executed for his part in the bombing.

Three days after the bombing, as I watched Tim McVeigh being led out of the courthouse, I hoped someone in a high building with a rifle would shoot him dead. I wanted him to fry. In fact, I’d have killed him myself if I’d had the chance.

Unable to deal with the pain of Julie’s death, I started self-medicating with alcohol until eventually the hangovers were lasting all day. Then, on a cold day in January 1996, I came to the bombsight – as I did every day – and I looked across the wasteland where the Murrah Building once stood. My head was splitting from drinking the night before and I thought, “I have to do something different, because what I’m doing isn’t working.”

For the next few weeks I started to reconcile things in my mind, and finally concluded that it was revenge and hate that had killed Julie and the 167 others. Tim McVeigh and Terry Nichols had been against the US government for what happened in Waco, Texas, in 1993 and seeing what they’d done with their vengeance, I knew I had to send mine in a different direction. Shortly afterwards I started speaking out against the death penalty.

I also remembered that shortly after the bombing I’d seen a news report on Tim McVeigh’s father, Bill. He was shown stooping over a flowerbed, and when he stood up I could see that he’d been physically bent over in pain. I recognized it because I was feeling that pain, too.

In December 1998, after Tim McVeigh had been sentenced to death, I had a chance to meet Bill McVeigh at his home near Buffalo. I wanted to show him that I did not blame him. His youngest daughter also wanted to meet me, and after Bill had showed me his garden, the three of us sat around the kitchen table. Up on the wall were family snapshots, including Tim’s graduation picture. They noticed that I kept looking up at it, so I felt compelled to say something. “God, what a good looking kid,” I said.

Earlier, when we’d been in the garden, Bill had asked me, “Bud, are you able to cry?” I’d told him, “I don’t usually have a problem crying.” His reply was, “I can’t cry, even though I’ve got a lot to cry about.” But now, sitting at the kitchen table looking at Tim’s photo, a big tear rolled down his face. It was the love of a father for a son.

When I got ready to leave I shook Bill’s hand, then extended it to Jennifer, but she just grabbed me and threw her arms around me. She was the same sort of age as Julie but felt so much taller. I don’t know which one of us started crying first. Then I held her face in my hands and said, “Look, honey, the three of us are in this for the rest of our lives. I don’t want your brother to die and I’ll do everything I can to prevent it.” As I walked away from the house I realized that until that moment I had walked alone, but now a tremendous weight had lifted from my shoulders. I had found someone who was a bigger victim of the Oklahoma bombing than I was, because while I can speak in front of thousands of people and say wonderful things about Julie, if Bill McVeigh meets a stranger he probably doesn’t even say he had a son.

About a year before the execution I found it in my heart to forgive Tim McVeigh. It was a release for me rather than for him.

Six months after the bombing a poll taken in Oklahoma City of victims’ families and survivors showed that 85% wanted the death penalty for Tim McVeigh. Six years later that figure had dropped to nearly half, and now most of those who supported his execution have come to believe it was a mistake. In other words, they didn’t feel any better after Tim McVeigh was taken from his cell and killed.

字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大