字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2011/08/14 07:20:08瀏覽1337|回應0|推薦0 | |

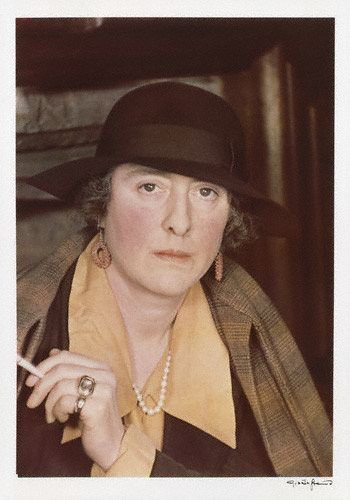

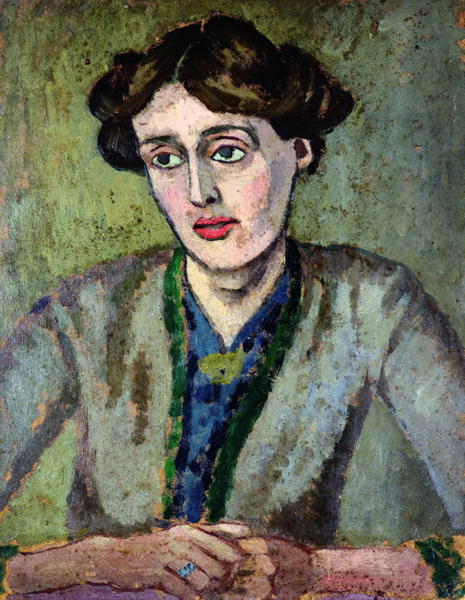

美麗佳人歐蘭朵 電影『美麗佳人歐蘭朵』也是改編自吳爾芙1928的作品『歐蘭朵』Orlando,『歐蘭朵』是Woolf 和小她十歲的美麗女詩人及雙性戀作家Vita Sackville-West ( 照片見下) 談戀愛而激發的作品, 後者同性戀史不斷, 還包括愛德華七世情婦的女兒, 兩人甚至相約棄夫私奔 ,因雙方夫婿懇求而阻止。Vita 的祖先是在Kent 郡的Knole 家族, 她繼承了此Knole 城堡,悠遠的貴族史與其特殊的氣質是Woolf的此書靈感所在。2002年底出版的新書『找不到出口的靈魂』(左岸出版),作者 Nigel Nicoleson 是著名的英國傳記作家,也是Vita 之子,他溫情而細膩地描繪出他自小眼中看到的Virginia,自然比啃讀Virginia書信猛猜測她內心的其他傳記作家真切許多。   有趣的是,繼普魯斯特(1871-1922)之後的兩位意識流巨匠Woolf與Joyce,竟然同年生死(1882-1941)! 死前不久, 即便對戰爭與靈感漸失的絕望,Woolf 都還信心滿滿地在日記中寫著 :「我還是會克服它, 並且燦然飛翔...... 」 。然而在1941年3-28,59歲的VW 還是把口袋裝入一大塊石頭,自溺於她Sussex home附近的river Ouse。VW 其實會游泳,此事件數天前,她也曾全身濕漉漉地返回孟克小屋,自稱無意失足落水。事後,家人才懷疑,之前那次恐怕已經是在嘗試自殺。她把兩封遺書(另一給畫家姐姐Vennesa)放置於花園的寫作小木屋內,帶著手杖,越過草原,沉入自己選擇的墓場。 在寫給丈夫Leonard Woolf 的信中,她說到自己的決定。”'Dearest, I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can't go through another of those terrible times. And I shan't recover this time. I begin to hear voices, and I can't concentrate. So I am doing what seems the best thing to do. You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be. I don't think two people could have been happier till this terrible disease came. I can't fight any longer. I know that I am spoiling your life, that without me you could work. And you will I know. You see I can't even write this properly. I can't read. What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good. I want to say that - everybody knows it. If anybody could have saved me it would have been you. Everything has gone from me but the certainty of your goodness. I can't go on spoiling your life any longer. I don't think two people could have been happier than we have been. “ 4-18,三週之後,她的遺體才被戲水小孩 在下游發現,原本,她意圖讓肉身「石沉大海」。 誰能不為之動容 ?她的自殺不是放棄,, 在那個對會幻聽的精神病(應是Maniac-depressive Psychosis)缺乏適當藥物的時代, 她只是想在"自己"還完整時把"故事"劃定句點。 她是永遠的、不死的 Orlando。  癡情男子終成空 雖然1912 Leonard Sidney Woolf ( 1880-1969) 娶了深愛的 Virginia ( 1882-1941),伴她至死,然而他是否曾真正觸及這個女子的內心,是個不解之謎。他的goodness 感動了她,然而隨著Mrs. Dalloway 的出版,她與生活週遭的疏離昭然若揭。 Leonard 也是Virginia 在Bloomsbury Group 的舊識,畢業劍橋大學,在Virginia 與此團體另一成員Lytton Strachey ( 慧慧提醒是他是gay)於1909解除婚約維持二十四小時的婚約後,自錫蘭當行政官員歸國的Leonard 向她求婚,時年她三十,受到老她許多的劍橋大學國王學院講師Walter Headlam熱烈追求,並遊戲於與Bloomsbury Group成員Hilton Young欲擒故縱的虛偽愛情中。Leonard 是個經濟學作家與評論家,即使蜜月看似幸運愉快,繼1895那次喪母發病後,VW再度於1915 病發,Leonard 形容她 "She talked almost without stopping for 2 or 3 days, paying no attention to anyone in the room or anything said to her ... Then gradually it became completely incoherent, a mere jumble of dissociated words." ,他仍然以深情見證參與了這位才女的後半生,並於她死後整體其散文日記出版。兩人早期的性關係使Virginia發現她無法從中得到期望的感受,這對夫婦逐漸捨棄肉體關係而成為真正的「靈魂伴侶」。 1917 年兩人共同成立Hogarth Press,並同時活躍於Bloomsbury Group聚會中,她的作品除前兩本外全由Hogarth Press出版。Bloomsbury Group始於1904,一群劍橋大學畢業生好友於敦倫此地定期每週四聚會飲酒談論,成員另有Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf(Virginia 夫), E. M. Forster, Vita Sackville-West, Roger Fry, Clive Bell(姐夫), and John Maynard Keynes (經濟學大師)。此團體自識甚高、立場左傾、並嚴格唾棄各領域任何代表封建保守勢力的圖騰,舉凡宗教、藝術、社會、性別議題皆然,此討論約延續至二次大戰左右,是1920年代英國文化界的特異份子。 有些人認為Leonard Woolf 應該為沒有預防到Virginia 的自盡負責,然而今日我們應該瞭解,對於躁鬱症患者而言,支持可能永遠不能完全避免悲劇,而Leonard長年默默伴隨,已屬不易。在Mrs. Dalloway 書裡,Virginia 已借女主角之意識說明,死亡只是維持人生命的完整與價值的陳述方式( Woolf saw death as a way to make a statement and a way to maintain the integrity and worth that is essential to giving life meaning. Death was a preservative in which to submerge the person when he might be compromised by the inanities and contamination of always bending to society.) 她的自盡早已自我預示,朋友凋零、靈感漸失,只是催化其步履。墓誌銘引用了1931出版的The Waves最後第九章Night 裡的一句話:Against you I will fling myself, unvanquished and unyielding, O Death!   VIRGINIA WOOLF 年表 1882. Born (25 Jan) Adeline Virginia Stephen, third child of Leslie Stephen (Victorian man of letters - first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography) - and Julia Duckworth (of the Duckworth publishing family). Comfortable upper middle class background. Brothers Thoby and Adrian went to Cambridge, and her sister Vanessa became a painter. Virginia was educated by private tutors and by extensive reading of literary classics in her father's library. 1895. Death of her mother. VW has the first of many nervous breakdowns. Father later remarries. 1897. Death of half-sister, Stella. VW learning Greek. 1899. Brother Thoby enters Trinity College, Cambridge and subsequently meets Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, and Clive Bell. These Cambridge friends subsequently become known as the Bloomsbury Group, of which VW was an important and influential member. 1904. Death of father. Beginning of second serious breakdown. VW's first publication is an unsigned review in The Guardian. Travels in France and Italy. VW moves to Gordon Square. 1905. Travels in Spain and Portugal. 1906. VW writing, reviewing, and teaching at Morley College evening institute for working men and women. Travels in Greece. Death of brother Thoby Stephen. 1907. Marriage of sister Vanessa to Clive Bell. VW moves with brother Adrian to live in Fitzroy Square. Working on her first novel (to become The Voyage Out). 1908. Visits Italy with the Bells. 1909. Lytton Strachey [homosexual] proposes marriage. VW meets Ottiline Morell, visits Bayreuth and Florence. 1910. First exhibition of Post-Impressionist painters arranged by Roger Fry. 1911. VW moves to Brunswick Square, sharing house with brother Adrian, Maynard Keynes, Duncan Grant, and Leonard Woolf. Travels to Turkey. 1912. Marries Leonard Woolf. Travels to Provence, Spain, and Italy. Moves to Clifford's Inn. 1913. Mental illness and her first attempted suicide. 1915. Purchase of Hogarth House, Richmond. The Voyage Out published and well received. Another bout of violent madness. 1917. L and VW buy hand printing machine and establish the Hogarth Press. First publication The Mark on the Wall. Later goes on to publish T.S. Eliot, Freud, and VW's own books. 1919. Purchase of Monk's House, Rodmell. Night and Day published. Brief friendship with Katherine Mansfield. Both are conscious of experimenting with the substance and the style of prose fiction. 1920. Works on journalism and Jacob's Room. 1922. Jacob's Room published. Meets Vita-Sackville West with whom she has a brief love affair. Writing encouraged by E.M. Forster, Strachey, and Leonard Woolf. 1923. Visits Spain. Works on early version of Mrs Dalloway. 1924. Purchase of lease on house in Tavistock Square. Gives lecture that becomes 'Mr Bennett and Mrs Brown'. 1925. The Common Reader [essays] and Mrs Dalloway published. Major break with the traditional novel, its form and techniques. 1927. To the Lighthouse published. Travels to Sicily. 1928. Orlando published - a fantasy dedicated to and based upon the life of Vita Sackville-West and her love of her ancestral home at Knowle, Sussex. 1929. A Room of One's Own published - essays on women's exclusion from literary history which have become of seminal importance in feminist studies. Travels to Berlin. 1931. The Waves - a novel composed of the thoughts of six characters which takes VW's literary experimentation to its natural limits. 1932. Death of Lytton Strachey. Begins The Years. 1934. Death of Roger Fry. Rewrites The Years. 1936. Begins Three Guineas - a 'sequel' to A Room of One's Own. 1938. Three Guineas extends the feminist critique of patriarchy, militarism, and privilege started in A Room of One's Own. 1939. Moves to Mecklenburgh Square, but lives mainly at Monk's House. 1940. Biography Roger Fry published. London homes damaged/destroyed in blitz. 1941. VW completes Between the Acts, her last novel, then fearing the madness which she felt engulfing her again, filled her pockets with stones and drowned herself in the River Ouse. VIRGINIA WOOLF SPEAKING~Virginia Woolf 聲音 This is the only surviving recording of Virginia Woolf's voice. It is part of a BBC radio broadcast from April 29th, 1937. The talk was called "Craftsmanship" and was part of a series entitled "Words Fail Me". The audio is accompanied by a slideshow of photographs of Virginia Woolf. The text was published as an essay in "The Death of the Moth and Other Essays" (1942), and I've transcribed the recorded portion here: http://atthisnow.blogspot.com/2009/06/craftsmanship-virginia-woolf.html Transcript: …Words, English words, are full of echoes, of memories, of associations. They have been out and about, on people's lips, in their houses, in the streets, in the fields, for so many centuries. And that is one of the chief difficulties in writing them today – that they are stored with other meanings, with other memories, and they have contracted so many famous marriages in the past. The splendid word "incarnadine," for example – who can use that without remembering "multitudinous seas"? In the old days, of course, when English was a new language, writers could invent new words and use them. Nowadays it is easy enough to invent new words – they spring to the lips whenever we see a new sight or feel a new sensation – but we cannot use them because the English language is old. You cannot use a brand new word in an old language because of the very obvious yet always mysterious fact that a word is not a single and separate entity, but part of other words. Indeed it is not a word until it is part of a sentence. Words belong to each other, although, of course, only a great poet knows that the word "incarnadine" belongs to "multitudinous seas." To combine new words with old words is fatal to the constitution of the sentence. In order to use new words properly you would have to invent a whole new language; and that, though no doubt we shall come to it, is not at the moment our business. Our business is to see what we can do with the old English language as it is. How can we combine the old words in new orders so that they survive, so that they create beauty, so that they tell the truth? That is the question. And the person who could answer that question would deserve whatever crown of glory the world has to offer. Think what it would mean if you could teach, or if you could learn the art of writing. Why, every book, every newspaper you'd pick up, would tell the truth, or create beauty. But there is, it would appear, some obstacle in the way, some hindrance to the teaching of words. For though at this moment at least a hundred professors are lecturing on the literature of the past, at least a thousand critics are reviewing the literature of the present, and hundreds upon hundreds of young men and women are passing examinations in English literature with the utmost credit, still – do we write better, do we read better than we read and wrote four hundred years ago when we were un-lectured, un-criticized, untaught? Is our modern Georgian literature a patch on the Elizabethan? Well, where then are we to lay the blame? Not on our professors; not on our reviewers; not on our writers; but on words. It is words that are to blame. They are the wildest, freest, most irresponsible, most un-teachable of all things. Of course, you can catch them and sort them and place them in alphabetical order in dictionaries. But words do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. If you want proof of this, consider how often in moments of emotion when we most need words we find none. Yet there is the dictionary; there at our disposal are some half-a-million words all in alphabetical order. But can we use them? No, because words do not live in dictionaries, they live in the mind. Look once more at the dictionary. There beyond a doubt lie plays more splendid than Antony and Cleopatra; poems lovelier than the Ode to a Nightingale; novels beside which Pride and Prejudice or David Copperfield are the crude bunglings of amateurs. It is only a question of finding the right words and putting them in the right order. But we cannot do it because they do not live in dictionaries; they live in the mind. And how do they live in the mind? Variously and strangely, much as human beings live, ranging hither and thither, falling in love, and mating together. It is true that they are much less bound by ceremony and convention than we are. Royal words mate with commoners. English words marry French words, German words, Indian words, Negro words, if they have a fancy. Indeed, the less we enquire into the past of our dear Mother English the better it will be for that lady's reputation. For she has gone a-roving, a-roving fair maid. Thus to lay down any laws for such irreclaimable vagabonds is worse than useless. A few trifling rules of grammar and spelling is all the constraint we can put on them. All we can say about them, as we peer at them over the edge of that deep, dark and only fitfully illuminated cavern in which they live – the mind – all we can say about them is that they seem to like people to think before they use them, and to feel before they use them, but to think and feel not about them, but about something different. They are highly sensitive, easily made self-conscious. They do not like to have their purity or their impurity discussed. If you start a Society for Pure English, they will show their resentment by starting another for impure English – hence the unnatural violence of much modern speech; it is a protest against the puritans. They are highly democratic, too; they believe that one word is as good as another; uneducated words are as good as educated words, uncultivated words as good as cultivated words, there are no ranks or titles in their society. Nor do they like being lifted out on the point of a pen and examined separately. They hang together, in sentences, paragraphs, sometimes for whole pages at a time. They hate being useful; they hate making money; they hate being lectured about in public. In short, they hate anything that stamps them with one meaning or confines them to one attitude, for it is their nature to change. Perhaps that is their most striking peculiarity – their need of change. It is because the truth they try to catch is many-sided, and they convey it by being many-sided, flashing first this way, then that. Thus they mean one thing to one person, another thing to another person; they are unintelligible to one generation, plain as a pikestaff to the next. And it is because of this complexity, this power to mean different things to different people, that they survive. Perhaps then one reason why we have no great poet, novelist or critic writing today is that we refuse to allow words their liberty. We pin them down to one meaning, their useful meaning, the meaning which makes us catch the train, the meaning which makes us pass the examination…   Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf (1911-12)  Painting of the writer Virginia Woolf by the artist Roger Fry.

|

|

| ( 不分類|不分類 ) |