字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/05 09:20:28瀏覽10|回應0|推薦0 | |

Steve Jobs resignsThe minister of magic steps down Can Silicon Valley’s most disruptive firm prosper without its maker?Aug 27th 2011 | SAN FRANCISCO | from the print edition

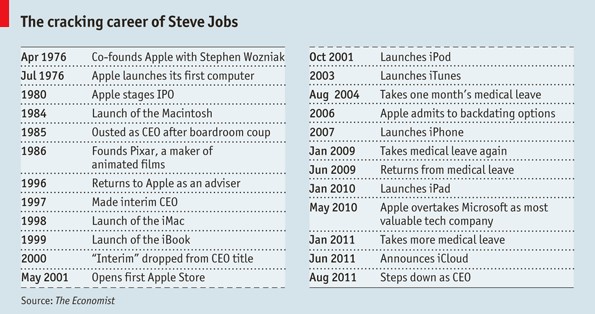

IN A commencement speech to students at Stanford University in 2005, Steve Jobs, the chief executive of Apple, advised his audience to avoid being trapped by dogma and to have the courage to follow their hearts and their intuition. “Stay hungry. Stay foolish,” he said as he signed off. By following his own advice, Mr Jobs, who resigned as Apple’s boss on August 24th, has turned the company from a basket case on the brink of bankruptcy when he returned to its helm in 1997 into a world-beater that is reshaping a big chunk of the technology industry. Earlier this month, Apple even briefly surpassed Exxon Mobil, an oil giant, to become the world’s most valuable company. No other boss in recent history has embodied and defined a firm as completely as Mr Jobs. So his decision to resign as chief executive has inevitably raised the question of whether Apple will remain as hungry and as wildly successful without its entrepreneurial maestro at the helm. Other giants in the tech industry have seen their fortunes fade after iconic leaders have departed. Microsoft has struggled to regain its mojo since Bill Gates stood down as its chief executive in January 2000. Could Apple suffer a similar fate? In this section · »The minister of magic steps down That seems unlikely for several reasons. One is that the company has had plenty of time to plan for this moment. Mr Jobs has stepped aside from day-to-day management at Apple on a couple of occasions before, after having surgery for a rare form of pancreatic cancer in 2004 (see timeline). Each time, Tim Cook, Apple’s chief operating officer, temporarily assumed his boss’s responsibilities. That allowed Mr Cook, who is taking over from Mr Jobs as CEO, to get a taste for the top spot—and it gave Apple’s board a chance to see him in action. On each occasion, Mr Cook kept Apple’s money-making machine ticking over smoothly. An expert in manufacturing and logistics, he closed down almost all of Apple’s manufacturing operations after he arrived at the firm in the late 1990s and outsourced much of these to Asia. Announcing his promotion, Apple’s board said that he had shown “remarkable talent and sound judgment in everything he does.” Talent is something that Apple also has an abundance of elsewhere in its ranks. Executives such as Phil Schiller, who oversees the company’s marketing, and Jonathan Ive, a Briton whose domain is design, are part of a team that has worked closely together for many years. If Mr Cook can keep this group intact, then Apple’s future should be bright. The firm also benefits from an intensely loyal and motivated workforce. Glassdoor, an online jobs and careers community, carries reviews of the company from almost 1,000 Apple employees. Most are glowing about the firm and in particular about Mr Jobs’s impact on it. One post even calls Apple’s former boss “the Thomas Edison of this century”. Paul Saffo of Discern Analytics, a financial-analytics company, reckons that this depth of loyalty will mean that even though Mr Jobs is stepping down, the firm’s employees will continue to ask themselves “what would Steve do?” when making decisions. (Of course, asking the question is easier than guessing the right answer.)

Another reason for optimism is that Mr Jobs is not disappearing from the scene entirely. Instead he is taking on a new role as the chairman of Apple’s board, which should allow him to keep weighing in on important decisions for some time to come, assuming that his health allows. Apple has a pretty clear product pipeline for the next couple of years, which is reassuring. The firm is due to unveil the latest version of its hugely successful iPhone in the coming weeks and is expected to launch a new iPad early next year. But Apple is far more than the sum of the devices that it sells, impressive though they are. Its secret sauce lies in the integration of these with software and services such as its iTunes online content store and its recently announced iCloud online-storage offering. These form what tech types like to call an “ecosystem” that has proved so popular that it is forcing other companies to develop similar capabilities. Google, which has long excelled at developing software, recently splashed out $12.5 billion for Motorola Mobility so that it could get its hands on the firm’s smartphones, tablets and other devices. And Amazon, which has a huge cloud business, is planning to launch its own tablet computer to compete with Apple’s iPad. The good news for Apple’s investors is that the firm has been given a great head start in the battle for dominance of this emerging tech landscape thanks to Mr Jobs, whose vision of the future has been honed over a long and tumultuous career. After co-founding Apple with Steve Wozniak in the 1970s, he went on to pioneer the era of the personal computer in the following decade. He was then ousted from Apple after a boardroom coup in 1985. After that, Mr Jobs followed his heart and his intuition by building up Pixar, a film studio that specialises in computer-animated films. It has produced a string of hits, from “Toy Story” to “Finding Nemo”. He returned to Apple as an adviser in 1996, when the firm was in dire straits. A year later he was made interim chief executive. Asked at the time what he thought Mr Jobs should do with Apple, Michael Dell, a rival computer-maker, helpfully suggested that he should shut it down. Mr Jobs ignored that advice. Instead he led the company on to its greatest triumphs. Among them were the creation of the iMac, which revived the firm’s ailing computer business, and the development of the iPod, which ended up transforming the music industry. But just as important as what Apple did was what it did not do. Charles Golvin of Forrester, a research firm, says that one of Mr Jobs’s greatest skills has been to decide which projects the firm should not undertake. It has been widely rumoured, for example, that engineers at Apple were urging its boss to create a tablet computer in the early part of the decade. But Mr Jobs turned a deaf ear to their entreaties and instead insisted that the company focus on producing a smartphone. The result was the iPhone, which transformed yet another market and is still minting money. In a creative cauldron like Apple, ideas are rarely in short supply. But the skill of choosing the right ones to focus on at the right time is rare. Mr Jobs has it. Apple’s shareholders will have to hope that Mr Cook does too. from the print edition | Business The minister of magic steps down Aug 25th 2011, 12:42

This is the news that make many people concerned about technology shocked again.

As many know that Steve Jobs is in apparantly worse health than ever before, we can easily understand why he still choose this way. Although his product is as clumsy as his face, it is impressed for me that Apple overtake Microsoft as the top brand of technology in May, 2010. He creates a different world from Microsoft’s window system and make many programme evolve into various form such as e-book(including the Economist), games, music and video players.

Among apple’s innovation, itunes is the most popular and iPad is the most economy production. Jobs is also known as the prominently stylish team leader of the world. When he suffers difficulties and some embarrassment in his bussiness, such as one year before he creates iPhone, he leads the six-person team and trys to put all the element of technology together from hardisk to software as soon as possible so that he can show his naughty personality and charisma. And in 2007’s autumn, Apple lauches the first iPhone in front of the people all over the world.

I still remember that in recent five years some writers publish well-known tip books showing how well he solidate the leadership and the ability of presentation. Especially “How to Be Insanely Great in Front of Any Audience” published by Mcgraw-Hill present his talent in presentation which most of the world leader hardly surpass.

I think the strong business can last for more than one decade. While Microsoft issues the sample of Windows 8 and expresses the Fujitsu-Toshiba Mango cell-phone, and faces the attack of HTC, Apple’s business is still expanding . Tim Cook also has a good ability to lead team, so this giant can keep his territory in short time. However, whether Apple can establish the new era and avoid the question of its too many copies of its last generation, no one can give any answer. The iPod is too expensive. And that’s why I still perfer Microsoft Windows Tablet and HTC Cherr Wang’s cell-phone. But itunes and AAC is not bad, ha, Jobs, thanks for your this innovation and take care of your health. Ha!!!

Recommended 13 Report Permalink 這篇寫於蘋果電腦創辦人賈伯斯要過世前一月,筆者陪眾人在這討論區集氣。雖然不是蘋果控,但喜歡各式音樂的筆者已將音樂盡數以aac格式收藏。在2010年5月蘋果的品牌價值超越了微軟。小小回顧幾點的突破,很簡單俐落的說賈氏生平,這篇除了幾個字母忘了校對之外,語句風格開始建立,也對固定主題有了心得。以後確立大部份而言,除了中國黨與國內及鄰近亞洲地緣政治,就是科技及商業類了,以及有時候聊起歷史故事。 (2018,08,05補充)附10月6日經濟學者雜誌的印刷版刊登的賈伯斯訃文 Obituary Steve JobsOct 6th 2011, 1:25 by T.S. | LONDON

NOBODY else in the computer industry, or any other industry for that matter, could put on a show like Steve Jobs. His product launches, at which he would stand alone on a black stage and conjure up a “magical” or “incredible” new electronic gadget in front of an awed crowd, were the performances of a master showman. All computers do is fetch and shuffle numbers, he once explained, but do it fast enough and “the results appear to be magic”. He spent his life packaging that magic into elegantly designed, easy to use products. He had been among the first, back in the 1970s, to see the potential that lay in the idea of selling computers to ordinary people. In those days of green-on-black displays, when floppy discs were still floppy, the notion that computers might soon become ubiquitous seemed fanciful. But Mr Jobs was one of a handful of pioneers who saw what was coming. Crucially, he also had an unusual knack for looking at computers from the outside, as a user, not just from the inside, as an engineer—something he attributed to the experiences of his wayward youth. Mr Jobs caught the computing bug while growing up in Silicon Valley. As a teenager in the late 1960s he cold-called his idol, Bill Hewlett, and talked his way into a summer job at Hewlett-Packard. But it was only after dropping out of college, travelling to India, becoming a Buddhist and experimenting with psychedelic drugs that Mr Jobs returned to California to co-found Apple, in his parents’ garage, on April Fools’ Day 1976. “A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences,” he once said. “So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions.” Bill Gates, he suggested, would be “a broader guy if he had dropped acid once or gone off to an ashram when he was younger”. Dropping out of his college course and attending calligraphy classes instead had, for example, given Mr Jobs an apparently useless love of typography. But support for a variety of fonts was to prove a key feature of the Macintosh, the pioneering mouse-driven, graphical computer that Apple launched in 1984. With its windows, icons and menus, it was sold as “the computer for the rest of us”. Having made a fortune from Apple’s initial success, Mr Jobs expected to sell “zillions” of his new machines. But the Mac was not the mass-market success Mr Jobs had hoped for, and he was ousted from Apple by its board. Yet this apparently disastrous turn of events turned out to be a blessing: “the best thing that could have ever happened to me”, Mr Jobs later called it. He co-founded a new firm, Pixar, which specialised in computer graphics, and NeXT, another computer-maker. His remarkable second act began in 1996 when Apple, having lost its way, acquired NeXT, and Mr Jobs returned to put its technology at the heart of a new range of Apple products. And the rest is history: Apple launched the iMac, the iPod, the iPhone and the iPad, and (briefly) became the world’s most valuable listed company. “I’m pretty sure none of this would have happened if I hadn’t been fired from Apple,” Mr Jobs said in 2005. When his failing health forced him to step down as Apple’s boss in 2011, he was hailed as the greatest chief executive in history. Oh, and Pixar, his side project, produced a string of hugely successful animated movies. In retrospect, Mr Jobs was a man ahead of his time during his first stint at Apple. Computing’s early years were dominated by technical types. But his emphasis on design and ease of use gave him the edge later on. Elegance, simplicity and an understanding of other fields came to matter in a world in which computers are fashion items, carried by everyone, that can do almost anything. “Technology alone is not enough,” said Mr Jobs at the end of his speech introducing the iPad, in January 2010. “It’s technology married with liberal arts, married with humanities, that yields the results that make our hearts sing.” It was an unusual statement for the head of a technology firm, but it was vintage Steve Jobs. His interdisciplinary approach was backed up by an obsessive attention to detail. A carpenter making a fine chest of drawers will not use plywood on the back, even though nobody will see it, he said, and he applied the same approach to his products. “For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.” He insisted that the first Macintosh should have no internal cooling fan, so that it would be silent—putting user needs above engineering convenience. He called an Apple engineer one weekend with an urgent request: the colour of one letter of an on-screen logo on the iPhone was not quite the right shade of yellow. He often wrote or rewrote the text of Apple’s advertisements himself. His on-stage persona as a Zen-like mystic notwithstanding, Mr Jobs was an autocratic manager with a fierce temper. But his egomania was largely justified. He eschewed market researchers and focus groups, preferring to trust his own instincts when evaluating potential new products. “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them,” he said. His judgment proved uncannily accurate: by the end of his career the hits far outweighed the misses. Mr Jobs was said by an engineer in the early years of Apple to emit a “reality distortion field”, such were his powers of persuasion. But in the end he changed reality, channelling the magic of computing into products that reshaped music, telecoms and media. The man who said in his youth that he wanted to “put a ding in the universe” did just that. (Photo credit: AFP) · Recommended · 76

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |