字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/09 00:40:29瀏覽208|回應0|推薦0 | |

Vaclav Havel 1936-2011Living in truthThe unassuming man who taught, through plays and politics, how tyranny may be defied and overcomeDec 31st 2011 | from the print edition

HAD communists not seized power in his homeland in 1948, Vaclav Havel would have been simply a distinguished Central European intellectual. That is how, triumphantly, he ended his career. In between came imprisonment, interrogations, house searches, isolation, heartbreak and betrayals—and adulation on the national and international stage. Although a highly successful politician, three times head of state and the leader of one of the most famous revolutions in history, he was not a natural public figure. A sincere, impatient and humble man, he detested the pomposity, superficiality and phoney intimacy of politics. Related topics Nor was he like most of his fellow dissidents, mainly ex-communist intellectuals whose glittering careers had been cut short by the Soviet-led invasion of 1968 and the purges that followed it. Mr Havel was never a communist. And he lacked formal academic education. He came from a rich family that had had most of its property nationalised after 1948. As a further punishment, he had to leave school at 15 and was allowed only a technical education, not the literary one he craved. He worked as a laboratory assistant, did military service (in mine-clearing, a task reserved for the politically suspect), and became a stage hand, studying drama by correspondence. As Czechoslovak communism softened in the 1960s, talented outsiders could begin to make their mark on the country’s cultural life. His first full-length play, “The Garden Party”, was performed in 1963. It was a wry look at the nonsense world of communist clichés. A middle-class family, hoping to help their son Hugo, sends him to meet some influential apparatchiks. He readily learns their meaningless office language and his career flourishes—though his parents can no longer understand him. Scrupulously careful in his choice of words, Mr Havel was especially alert to, and annoyed by, the atrocious effects of communism on his mother tongue. His next play, “The Memorandum”, first performed in 1966, dealt with an invented language, Ptydepe, designed (like communism) to eliminate ambiguity and promote efficiency, but with little regard for practicality or humanity. Its introduction, in an absurd workplace filled with sinister snoopers, creates chaos and deadlock. Such mockery of the system was tolerated, even encouraged, before and during the Prague Spring, when reformist communists under Alexander Dubcek abolished censorship and tried to create what they called “socialism with a human face”. But that experiment was intolerable to Leonid Brezhnev’s Soviet Union, just as Mr Havel’s work was to the grey apparatchiks installed by the Warsaw Pact’s tanks. The plays were staged in New York and elsewhere, but their author—like millions of others now a prisoner in his own country—was unable to see them. Banned from working in the theatre, he briefly took a menial job in a brewery; he wrote about that in another play, “Audience”. Few had the stomach to struggle on against communism after such a comprehensive defeat. Many Czechs and Slovaks glumly resolved to make the best of a bad situation. Not Mr Havel: words were his weapons, and he intended to use them. In early 1975 he wrote a caustic letter to the communist leader Gustav Husak, saying that the “calm” which the authorities regarded as their great achievement was in fact a “musty inertia…like the morgue or a grave.” Under the coffin-lid of communism, the country was rotting: “It is the worst in us which is being systematically activated and enlarged—egotism, hypocrisy, indifference, cowardice, fear, resignation, and the desire to escape every personal responsibility…” With a handful of allies Mr Havel then collected 242 public supporters for what would be the first open manifestation of dissent inside the Soviet empire: Charter 77, a declaration that highlighted the authorities’ breaches of the international human-rights standards to which they had notionally subscribed. The reaction was venomous. Those who refused to denounce the document brought severe punishments on themselves and their families. One of the three founding spokesmen, Jan Patocka, a philosophy professor, died during a gruelling 11-hour interrogation. Mr Havel, another, spent five months behind bars in 1977, with a further three months in 1978. But the crackdown spurred rather than deterred him. Taking advantage of lax border controls in a national park on the Czechoslovak-Polish border, Mr Havel led a bunch of friends in the summer of 1978 to meet a group headed by Adam Michnik, the brainbox of the Warsaw opposition. Mr Michnik recalls a “magic moment” as Mr Havel (Vasek to his friends) pulled cheese, bread and vodka from a knapsack and they began to “build the foundations of the international anti-Communist community…we had decided to shed our gags and to confront the totalitarian dictatorship face to face.” The greengrocer’s tale The practical result of the cross-border meeting was a joint collection of essays. One was Mr Havel’s: “The Power of the Powerless”, a reflection on the mind of a greengrocer who obediently puts a poster “among the onions and carrots” urging “Workers of the World—Unite!” In gentle, ironic but scathing prose, Mr Havel exposed the lies and cowardice that made possible the communist grip on power. The greengrocer puts up the poster partly out of habit, partly because everyone else does it, and partly out of fear of the consequences if he does not. Just as the “Good Soldier Svejk” encapsulated the cowardly absurdity of life in the Austro-Hungarian army, Mr Havel’s greengrocer epitomised the petty humiliations of “normalised” Czechoslovakia. Yet the greengrocer would balk if he were told to display a poster saying: “I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient.” That was the difference between the terrified conformity of the Stalinist era and the collusive charade between rulers and ruled that prevailed in the 1970s. The people pretended to follow the Party, and the Party pretended to lead. Those shallow foundations were vulnerable to individual acts of disobedience. Just imagine, Mr Havel wrote, …that one day something in our greengrocer snaps and he stops putting up the slogans merely to ingratiate himself. He stops voting in elections he knows are a farce. He begins to say what he really thinks at political meetings. And he even finds the strength in himself to express solidarity with those whom his conscience commands him to support. In this revolt the greengrocer steps out of living within the lie. He rejects the ritual and breaks the rules of the game. He discovers once more his suppressed identity and dignity. He gives his freedom a concrete significance. His revolt is an attempt to live within the truth ... That would bring ostracism and punishment, but imposed for compliance’s sake, not out of conviction. His real crime was not speaking out, but exposing the sham: He has shattered the world of appearances, the fundamental pillar of the system...He has demonstrated that living a lie is living a lie. He has broken through the exalted façade…and exposed the real, base foundations of power…He has shown everyone that it is possible to live within the truth. Living within the lie can constitute the system only if it is universal…everyone who steps out of line denies it in principle and threatens it in its entirety ... The phrase “living in truth” was Mr Havel’s hallmark. No single phrase did more to inspire those trying to subvert and overthrow the communist empire in Europe. In 1979 he received a five-year prison sentence. This was the darkest time of his life. The outside world showed little interest. The dissident movement was shrivelling under the harassment of the StB, the Czechoslovak counterpart of the KGB. In Poland, Solidarity was crushed by martial law. And in prison he could not write, barring a weekly letter to his wife. The commandant, a Stalinist-era veteran, enjoyed tormenting his top prisoner, confiscating the whole letter if any bit breached prison rules (personal matters only, no foreign words, no underlining, no discussion of philosophy). The result, in elliptical and sometimes baffling prose, was “Letters to Olga”, a book that could be published only abroad. He was released early, with severe pneumonia, in 1983. His health never recovered, and his heavy smoking gave it little chance to.

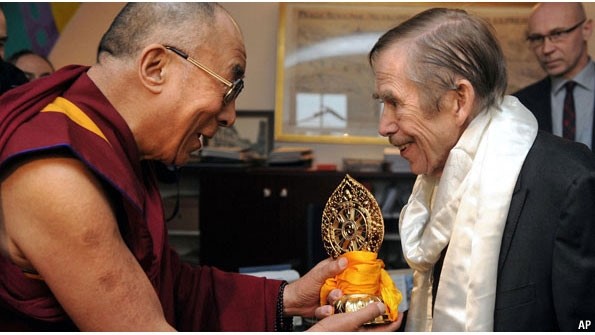

Appropriate uniforms

That gloom proved to be the nadir. Once the enforcer of communist orthodoxy, the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev became a spur to change: that shift inspired democrats and sapped their persecutors. In Hungary and Poland the regimes were weakening visibly by the late 1980s, but Czechoslovakia’s Communist blockheads continued to beat, bully and jail their opponents. Mr Havel was sentenced to eight months for “hooliganism” in early 1989. But this time his jailing sparked outrage, not apathy. In Poland one of his plays was performed publicly—with the communist prime minister in the audience. Citing his “exemplary behaviour”, the Prague regime in April freed its most famous prisoner early. That evening stokers, street-sweepers and window-washers—in earlier life musicians, philosophers and writers—partied at the former stagehand’s home. By the year’s end, they would be toasting his presidency. A moral compass Yet Czechoslovakia’s dissident movement was still tiny and amateurish, way behind Poland’s Solidarity in muscle, or Hungary’s activists in sophistication. Mr Havel and his pals were all but unknown in their own country. Change was in the air, but many were uneasy about what it might bring: economic upheaval, American imperialism, the return of vengeful émigrés, German revanchism or Jewish property claims. The authorities tried to tar the dissidents as CIA stooges, and Mr Havel as the scion of a family of Nazi collaborators. But propaganda was no substitute for reform. Though the dissidents were feeble, they were kicking at a rotten door. Mr Havel was fast becoming a political leader. It was not a role he enjoyed. Foreign visitors queued outside his apartment, cutting into his time for reading, writing, thinking and talking. At times he retreated to his country cottage for peace and quiet. When in Prague he kept his appointments on a small scrap of folded paper in his pocket: he was not a politician and was not going to behave like one. His main defence was a venerable old man called Zdenek Urbanek (author of the country’s best translation of “Hamlet”, but disgraced after 1968), whose stately good manners and quavering English could deter even the pushiest television crews. But events brushed diffidence aside. As the Soviet empire crumbled the Communist Party leader, Milos Jakes, in a leaked recording, could be heard complaining to his comrades (in ludicrously ungrammatical Czech) that the country was “the last pole in the fence”. Hungarians and Austrians picnicked on what had once been the Iron Curtain’s barbed-wire cordon. Even loyal East Germany wobbled and toppled. When the Prague riot police brutally broke up a student demonstration on November 17th 1989, Mr Havel and his colleagues set up the Civic Forum—a determinedly non-partisan group with, at first, no leaders. Day after day and in ever-increasing numbers the demonstrators of the Velvet Revolution filled Wenceslas Square, chanting “Truth will triumph” and “We’ve had enough”. Intellectuals had played a vital role in fostering Czech and Slovak national feelings during the Habsburg empire and in building pre-war Czechoslovakia. Now they were taking charge again. Behind the scenes (literally) of the Magic Lantern Theatre, where Civic Forum set up itsheadquarters, Mr Havel’s quiet authority and moral compass made him the unquestioned head of the opposition. Others were more forceful, self-important or impetuous. But it was the playwright’s voice that counted. On November 24th, during a press conference, the news came through that the entire leadership of the Communist Party had resigned. Someone produced a bottle of fizzy wine. Mr Havel, next to a beaming Dubcek (hotfoot from his job as a humble forester), declared a toast: “Long live a free Czechoslovakia.” The regime had in effect surrendered, and the country’s destiny was in the writer’s hands. In 24 hours in early December, in what he later said was the most difficult decision of his life, Mr Havel reluctantly agreed to stand for president; posters saying Havel na Hrad(Havel to the Castle) already festooned Prague. Duty (and perhaps a sense of mischief) had triumphed over his craving for a return to normal life. He was elected unanimously by the discredited communist-era parliament, and again in June by its freely elected successor. Many dissidents’ political careers flared in 1989 but fizzled thereafter: they were too individualistic, or principled, or eccentric for the demands of public life. Mr Havel was the glorious exception. He confounded those who thought he was too dilettantish and self-effacing to be a proper president. He and his pony-tailed, scooter- riding advisers romped through the corridors of Prague Castle, exorcising the ghosts of the communist usurpers with humanity and humour. He ordered spectacular floodlighting, and gloriously elaborate comic-opera uniforms to replace its guards’ grim garb. Almost his first act in office was to invite the rock musician Frank Zappa to a joyful victory concert in Prague. In what would be a hallmark of his later political life, he made a point of helping beleaguered but like-minded figures. He became a close friend of the Dalai Lama, who was almost the first foreign dignitary he received as president. In 1991 he lobbied for Aung San Suu Kyi’s Nobel peace prize, when it could have been his. His last public statements were to support political prisoners in Belarus and the opposition protests in Russia. In return, the Kremlin issued insultingly sparse condolences. But in Moscow on December 24th (see article) 80,000 pro-democracy demonstrators held a minute’s silence in his memory.

Soul mates

Mr Havel banished many demons. He opened warm diplomatic ties with Israel and befriended Germany, then a bogeyman for many Czechoslovaks. He brought Pope John Paul II to Prague, overcoming a neurotic anti-Catholicism and secularism among some of his compatriots, who harboured lively resentments of the counter-Reformation and priestly privilege. His record at home was more mixed. The parliamentary system gave the president little executive power. With first-hand experience of the flaws in the justice system, he freed many prisoners: some blamed that for a subsequent crime wave. He disliked the arms industry, and tried to block some important deals. But making weapons was a big source of jobs in Slovakia, long the poorer part of the country, where many felt Mr Havel had a tin ear for their concerns. He was unable to stop the ambitious politicians in Prague and Bratislava who were scheming to dissolve Czechoslovakia. That seemed a big failure at the time. Yet the smooth and peaceful “velvet divorce” of 1992 was a huge achievement. Mr Havel is much mourned in Slovakia; the two countries now get on better than ever. Laying ghosts He returned as president of the Czech Republic in 1993 and again in 1998, making the most of his largely symbolic role. Thegreat triumphs were accession to NATO (in 1999) and laying the foundations for European Union membership in 2004. The country could not have had a better ambassador. In 1994 he lured President Bill Clinton into a joyful impromptu saxophone session at a Prague nightclub. He was profoundly uneasy (rightly, in retrospect) with the shaky moral foundations of post-communist capitalism. The economic reformers understood markets, but not mankind: loose rules and weak institutions created a spivs’ paradise, with a malign and lasting legacy of corruption. The StB was disbanded, but with almost no accounting for its crimes. Mr Havel himself reckoned that the biggest failure on his watch was the handling of the secret police files, a toxic mix of guilty secrets and malicious invention that leaked into public view in the 1990s. Some Czechs disliked him: too preachy, too elitist, they said (too brave and honest for a country prone to moral flexibility, said others). His critics’ main charges were that he regained family property (entirely lawfully) and then got bogged down in a squabble about its division (not his fault). After his wife Olga died in 1996, he remarried, just under a year later, a lively and rather younger actress, Dagmar, whom some found vulgar in comparison. (Mr Havel said plaintively: “We are in love and want to be together.”) His plays were overrated (perhaps, but his essays deserved every plaudit). He enjoyed the fruits of commercial success (entirely merited, unlike some of his compatriots’ fortunes). Out of office, Mr Havel’s restless Bohemian energy stayed with him even as his physical strength ebbed. He resumed his literary career, fulfilling a lifetime dream of directing a film—about a politician leaving power. An engaging memoir of his time as president captured the atmosphere of Prague Castle in what to his friends were fairytale years. It was Mr Havel’s genius that he not only toppled communism, but offered a way out of its ruins that all could follow: calming nerves, laying ghosts and precluding revenge. He had a better claim to resentment than most. But he showed no sign of being burdened by the past. He was far happier about things that had gone successfully than cross about those that had gone wrong. Although humble enough to know he was not a perfect man, he was confident that his ideas were right. His favourite motto summed it up: “Truth and love must prevail over lies and hate.” from the print edition | Briefing View all comments (12)Add your comment 以下原文摘自經濟學者當時的ex-Communist欄的部落格版訃文(2018,08,05補充),而上方的是印刷版的訃文 http://www.economist.com/blogs/easternapproaches/2011/12/v%C3%A1clav-havel-memoriamVáclav Havel: in memoriamVáclav Havel, playwright and presidentDec 18th 2011, 13:02 by E.L.

EARLY in 1989, your correspondent, newly arrived in communist Czechoslovakia, passed an empty building in the Podoli district of Prague. Someone had written in the grime inside the window: “Svoboda Havlovi” [Freedom for Havel]. It was an interesting moment. The jailed playwright (as we used to call him) was behind bars for hooliganism following an opposition demonstration. The authorities could jail individuals. But they had lost the will, or the capability, to police the inside of shop windows. The slogan (which was still there a year later when Mr Havel was president) was particularly striking because shop windows were the theme of one of Václav Havels best-known essays. In "The Power of the Powerless", he ponders the presence of a banal communist propaganda poster, reading "Workers of the world, unite!" in a greengrocers window. Why does he do it? What is he trying to communicate to the world? Is he genuinely enthusiastic about the idea of unity among the workers of the world? Is his enthusiasm so great that he feels an irrepressible impulse to acquaint the public with his ideals? Has he really given more than a moments thought to how such a unification might occur and what it would mean? I think it can safely be assumed that the overwhelming majority of shopkeepers never think about the slogans they put in their windows, nor do they use them to express their real opinions. That poster was delivered to our greengrocer from the enterprise headquarters along with the onions and carrots. He put them all into the window simply because it has been done that way for years, because everyone does it, and because that is the way it has to be. If he were to refuse, there could be trouble. He could be reproached for not having the proper decoration in his window; someone might even accuse him of disloyalty. He does it because these things must be done if one is to get along in life. It is one of the thousands of details that guarantee him a relatively tranquil life "in harmony with society," as they say. That encapsulated the way many Czechs and Slovaks dealt with their fate after the Soviet-led invasion of 1968. To many outsiders the country seemed numb, the subject of a kind of moral castration. Resistance was useless: even if you changed the system, the Soviet tanks would crush what you attempted. So the only solution was to withdraw into internal (or, for a few, external) exile. The cocktail that fuelled totalitarianism was a mixture of fear and pretence: the greengrocer pretended to be loyal for fear of the consequences. Havel noted later in his essay: If the greengrocer had been instructed to display the slogan "I am afraid and therefore unquestioningly obedient; he would not be nearly as indifferent to its semantics, even though the statement would reflect the truth. The greengrocer would be embarrassed and ashamed to put such an unequivocal statement of his own degradation in the shop window, and quite naturally so, for he is a human being and thus has a sense of his own dignity. To overcome this complication, his expression of loyalty must take the form of a sign which, at least on its textual surface, indicates a level of disinterested conviction. It must allow the greengrocer to say, "Whats wrong with the workers of the world uniting?" Thus the sign helps the greengrocer to conceal from himself the low foundations of his obedience, at the same time concealing the low foundations of power. But those shallow foundations were vulnerable to individual acts of disobedience. Havel concludes his essay thus: Let us now imagine that one day something in our greengrocer snaps and he stops putting up the slogans merely to ingratiate himself. He stops voting in elections he knows are a farce. He begins to say what he really thinks at political meetings. And he even finds the strength in himself to express solidarity with those whom his conscience commands him to support. In this revolt the greengrocer steps out of living within the lie. He rejects the ritual and breaks the rules of the game. He discovers once more his suppressed identity and dignity. He gives his freedom a concrete significance. His revolt is an attempt to live within the truth. . . . That would come at a cost: He will be relieved of his post as manager of the shop and transferred to the warehouse. His pay will be reduced. His hopes for a holiday in Bulgaria will evaporate. His childrens access to higher education will be threatened. His superiors will harass him and his fellow workers will wonder about him. Most of those who apply these sanctions, however, will not do so from any authentic inner conviction but simply under pressure from conditions, the same conditions that once pressured the greengrocer to display the official slogans. They will persecute the greengrocer either because it is expected of them, or to demonstrate their loyalty, or simply as part of the general panorama, to which belongs an awareness that this is how situations of this sort are dealt with, that this, in fact, is how things are always done, particularly if one is not to become suspect oneself. The executors, therefore, behave essentially like everyone else, to a greater or lesser degree: as components of the post-totalitarian system, as agents of its automatism, as petty instruments of the social auto-totality. Havel concluded with his most famous exhortation: to live in truth was to deny the communist system its legitimacy, and ultimately its power: Thus the power structure, through the agency of those who carry out the sanctions, those anonymous components of the system, will spew the greengrocer from its mouth....The greengrocer has not committed a simple, individual offence, isolated in its own uniqueness, but something incomparably more serious. By breaking the rules of the game, he has disrupted the game as such. He has exposed it as a mere game. He has shattered the world of appearances, the fundamental pillar of the system. He has upset the power structure by tearing apart what holds it together. He has demonstrated that living a lie is living a lie. He has broken through the exalted facade of the system and exposed the real, base foundations of power. He has said that the emperor is naked. And because the emperor is in fact naked, something extremely dangerous has happened: by his action, the greengrocer has addressed the world. He has enabled everyone to peer behind the curtain. He has shown everyone that it is possible to live within the truth. Living within the lie can constitute the system only if it is universal. The principle must embrace and permeate everything. There are no terms whatsoever on which it can co-exist with living within the truth, and therefore everyone who steps out of line denies it in principle and threatens it in its entirety... Havel practised what he preached. He himself was denied higher education, as the scion of a famous bourgeois family. Others might have curried favour by writing plays praising the regime. But he worked as a stage-hand, and studied drama in his spare time. As Czechoslovak communist rule eased in the 1960s, his plays were performed, and gained public acclaim. By 1968, he was a well-known and successful playwright. For him and the rest of the countrys cultural elite, the Soviet-led invasion posed a sharp problem: emigrate, collaborate, or face the consequences. Philosophers became stokers, and poets street-sweepers. Havel took a job in a brewery (which he wrote about in his play "Audience"). In the mid 1970s he moved into active opposition to the regime, defending the underground rock group Plastic People of the Universe and, in 1977, signing the dissident declaration "Charter 77". The late 1970s were tough years for the captive nations of the Soviet empire. Havel was jailed from 1979 to 1984, during which he wrote the letters to his wife, Olga, that later became part of perhaps his best-known book. He also spent many days under arrest and interrogation. Out of jail, his every move, visitor, letter, phone call and utterance were subject to scrutiny by the StB, the secret-police servants of Czechoslovakias communist masters. His last bout of imprisonment came in happier circumstances. Communism was crumbling across the whole of the Warsaw Pact. in Poland his close friends and allies from Solidarity were on the verge of meeting their exhausted persecutors across (or to be more precise around) the negotiating table. At his parole hearing in April, the journalists, diplomats and friends (not exclusive categories) in the courtroom listened as prison officials solemnly gave evidence of the prisoner’s good behaviour. They could say nothing about his rehabilitation, but he had certainly not broken any prison rules. The small, tubby figure beamed and winked. That evening brought a mighty celebration in the palatial rooms of his riverside apartment. Many of those present had spent the last 20 years as the victims of the regimes bullying: for some, the fate was menial labour. For others, it was broken marriages, or children whose life chances were blighted (the StB would often use threats to childrens welfare to browbeat the stubborn). The sense of bravery and resistance, matched with impending triumph, was palpable. The regime itself might not know it, but its victims did: the days of the old grey men with cold grey faces were numbered. Havel was the de-facto leader of the Czechoslovak dissident movement, but it was not a role he enjoyed. He hated the intrusive phone calls from newspapers and radio stations, often retreating to his country cottage for some peace and quiet. He kept his appointments list on a small scrap of folded paper, sometimes entrusted to his beloved friend Zdeněk Urbánek, whose stately good manners and quavering English could deter even the pushiest television crews (many would turn up unannounced, determined to interview the "opposition leader" on the spot, regardless of convenience or even agreement). His habitual and even plaintive refrain was that he was a playwright, not a politician. His only desire was for a political system in which he could do the only job that he felt truly qualified to do. But events brushed such diffidence aside. After the riot police brutally broke up a student demonstration on November 17th1989 Havel and his colleagues set up the Civic Forum—a determinedly non-partisan group that initially had no leaders. But it was leadership that the demonstrators wanted as they swelled Wenceslas Square each day, always in greater numbers. As the regime opened negotiations with Civic Forum, and as heads rolled in both the party and the government, posters saying “Havel na Hrad” (Havel to the Castle) began appearing. In December he reluctantly agreed to run for president (forestalling an attempt to put forward the architect of the Prague Spring, Alexander Dubček). A bunch of cheeky Poles tried to get in on the act too, with posters saying “Havel na Wawel”. If the Czechoslovaks didn’t want him, they would make him king of Poland, to be crowned at the Wawel castle in Cracow. Havel confounded those who thought he was too dilettantish to be a proper president. He rollerskated through the corridors of Prague castle, exorcising the ghosts of the communist usurpers with his humanity and humour. His addresses to his fellow citizens on New Years Eve 1989 and 1990 make illuminating and moving reading. In what would be a hallmark of his political approach, he made a point of lending support to beleaguered but like-minded figures abroad. He invited the Lithuanian leader Vytautas Landsbergis to Prague, as that country struggled to turn its declaration of independence from Soviet occupation into reality. He brought the Pope to Prague, overcoming the neurotic anti-Catholicism and secularism of some Czechs, who remember the counter-Reformation and priestly privilege as if they were yesterday. He was a close friend of the the Dalai Lama—almost the first foreign dignitary he received as president, and a visitor in the last days of his life. Others might counsel friendship with the mighty Chinese; for Havel matters of principle were just that. Having themselves been forgotten captives, the Czechs could not possibly forget the plight of the Tibetans, the Uighurs, the Belarusians and the Cubans. He laid other ghosts of the past too: opening warm diplomatic ties with Israel and giving full co-operation to outside efforts to track down the many Arab terrorists who had trained in Czechoslavakia under communism. He also made a point of friendly ties with Germany—in those days a bogey figure for many Czechs and Slovaks, who feared that the expulsion of Sudeten and other Germans after 1945 was neither forgiven nor forgotten. He hosted the great Richard von Weizsäcker in Prague castle, issuing a carefully worded joint presidential declaration that, thanks to some fancy footwork with Czech grammar, squared the circles of Czech and German resentments about history. He did not succeed in saving Czechoslovakia from the depredations of ambitious politicians in Prague and Bratislava, who saw great possibilities for their own advancement in smaller and separate countries. But he returned as president of the Czech Republic in 1993 and again in 1998, piloting his country into the European Union and NATO. His great aim, he used to say, was that his countrymen could enjoy life untroubled by politics. But that was only one of his achievements. As a playwright and as an essayist, and as a philosopher of the human condition, his fame stretched far beyond the "small boring European country" whose return to freedom he had so lovingly overseen. (Picture credit: AFP)

Resting in glory Dec 27th 2011, 18:49

Recalling the 1968’s Prague Spring, the indignant misfortune for Czechs, Václav Havel became the pro-democracy leader striving for the independent freedom from Soviet Union. For several times, there are acrimonious comparisons as well as critics among the democratic affairs such as 1989’s Tiannanmen Square and 1991 Berlin Wall. Intensively in recent week, the Economist.com provides many articles concerned of Kim Jeon-Il and Václav Havel recently died letting us once again profoundly think the meaning of democracy.

The most well-known thought of Václav Havel is that human right is more important than any nation’s sovereignty. He does this concern very discreetly. Second to none, the value of modern democracy fully reflects on how and what he donates himself on Czech. In his presidency, U.S. President Bill Clinton and George W. Bush are both his good friends and mirror of each other. Taiwan’s then prime minister Lien Chan once took a trip to Prague experiencing his hard work. In addition, he visited some countries with his literature to meet many world leaders including Taiwan’s Chen Shui-Bian in 2004. Today, more yesterday’s memories become so far away.

Czech is the place where many bohemian artists was born. Like 19th century’s Antonín Dvorák and Bedřich Smetana, people in Czech always show their patriotism anytime and anywhere. The most spiritual Czech art “Má Vlast, cycle of 6 symphonic poems: No 2, Vltava (Moldau)” maybe ultimately pay tribute to you, Havel.

Recommended 5 Report Permalink Havels funeralResting in gloryDec 24th 2011, 12:18 by K.Z. | PRAGUE REINHARD HEYDRICH, the wartime Nazi boss of Bohemia and Moravia, is said to have called Czechs laughing beasts. Yes, Czechs canbe subversive, disparaging and unpatriotic. Most flee cities to chill out at their country homes on national holidays. Four decades of Communist rule, with its mandatory May Day parades and other empty socialist rites cemented Czech disgust of state rituals. Václav Havel, a pedantic master of ceremonies, placed importance on forming new public rituals in the newly democratic state. His passing on Sunday showed how to return meaning to public rituals. Thousands of Czechs flocked to the Prague Castle on Friday for the last occasion to bid farewell to their president: Czechoslovakias last and the Czech Republics first. The mourners wore tricolour ribbons in national red, blue and white just as in the days of the Velvet Revolution that brought down Communist rule in 1989. Some said they came to relive the friendly mutuality of those revolution days. "He was a brave man compared to the rest of our politicians. He was not arrogant and he did not steal," said Jana Kubanova, 30, who brought her four-month-old daughter. Many young people in the crowd would have had only a faint recollection of the Communist rule, if any and the Velvet Revolution that brought Havel to power. We are losing the greatest Czech of our time, of our modern history," said Michal Murad, 25, a law student from Strakonice. "He represents my first memories. I was three years old and I remember him speaking from a balcony." It did not put off Havels fans that the pompous state funeral, whose bits were partly modeled on the memorial ceremonies for Czechoslovakias first president Tomas Garrigue Masaryk, was orchestrated by his arch enemy and successor in office, Václav Klaus. "That is really like a twist from one of his absurd plays," said political analyst Jiří Pehe, Havels collaborator and former adviser. Klaus, who publicly spoke about Havel three times since he died on Sunday, stayed away from bashing his predecessor. "Those of us who like Havel were worried when Klaus began to speak," said Martina Utikalová, 47, a midwife from Kladno. "I was surprised that what he said was actually nice." At times it seemed that for his admirers and close associates, Havel has become an infallible God-like cult figure. When this reporter visited the set of Havels film debut based on his last play, Leaving, she could not find a single detractor. When the film opened, most reviewers took pains not to slam the ex-president. After departure from office, Havel, who was nervous about returning to writing plays instead of speeches, once lamented to an interviewer that it was difficult to elicit an honest opinion of his work from his friends. But a great number of his fellow countrymen were not enthusiastic about their former leader. Czechs often condemned Havel as a naive elitist, too detached from realities of their everyday lives during the painful transformation from an ailing centrally-planned economy to capitalism. Many blamed the president for the countrys economic woes. The overhaul, spearheaded by free-market-worshipping Klaus, was tainted by vast embezzlement and corruption. Havel, himself frustrated with the theft and fraud, turned from the Velvet Revolutions hero to the nations lightning rod. (Picture credit: AFP) 這篇筆者回顧布拉格之春的蘇維埃軍隊的無恥及台灣和哈維爾前故總統的與2000s的扁連關係都很好,很即興的給了莫爾島河民謠,爾後筆者有再深入閱讀Mark Kurlansky的「1968: The Year That Rocked The World.」之後的文章會有提到。願哈氏安息於榮耀光環之中,小遺憾當年沒有較系統地給哈氏訂一本小傳。 |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |