字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2019/08/07 20:20:04瀏覽642|回應0|推薦5 | |

不搭 烽火連三月的敘利亞 有著世界最古老的香皂 作者從他老爸的一卡舊皮箱裡,翻出放到已經變黑金的阿勒坡皂,小時候他一度有點排斥,羨慕同學有繽紛帶有人工香味的香皂,年紀漸長他才體會出阿勒坡皂曖曖內含光的本質,以及感念幾個世代傳承的歷史。 阿勒坡皂,嚴格說來是世界上歷史最悠久,第一塊打磨出長方形的香皂,而且配方很簡單,就橄欖油 + 月桂油 + 皂鹼,加上古羅馬時期大家重視沐浴文化,總要到澡堂洗洗刷刷,愛美又重視保養,而且在那個場合還會進一步聊可以怎樣再更精緻化香皂。日常生活,對於香皂非常精雕細琢。 在敘利亞阿勒坡,有著圍繞這款香皂所形成的產業鏈,包括:從採摘植物、到工廠、通路、到終端市集。但因為連年戰火,所有的人都落跑。現在敘利亞政府終於有能力把這塊地方圈起來保護著,所以肥皂製造商又一一回籠,但談到全面回歸還有點太早。兩百多家行號,目前只有二十家捲土重來。受訪同時,他們慶幸自己命還在,才能這樣重起爐灶。 不知何時開始,我們打造新商品,總要寫『品牌故事』。但沒有東西,怎麼寫?其實就是要賺錢,但怎麼能赤裸裸講出來。少了一味,少了時間去釀造的東西,青澀的東西怎麼講故事? 讀這一篇文章,有種深深的感動。 阿勒坡形成一個情感與營生的網格,一塊皂養活整個城市的人,而且是幾代傳承的家族事業。既要靠它維生,又有世代傳承的濃厚情感。一年到頭被戰亂騷擾,卻有強勁的生命力,原地站起。 每一塊香皂,不管製程如何不同,最後會蓋上一個阿勒坡原產地的印章,外加阿拉伯語。嗯……….這東西已經有種『香皂魂』在裏頭了。你說配方很簡單,依樣畫葫蘆,做出來的就不是阿勒坡皂。這是歲月與歷史、與人文地理風情去釀造出的皂,完全無法複製。也是現代人最缺失(想追尋)的一塊,兼顧商業利益與獨一無二的商品魂。沒有誇大花俏的行銷,也沒有尖端革新的科技,只是天地餵養,讓人能獨立於其中的自給自足。 原文連結(有更清楚的說明) https://www.atlasobscura.com/…/in-syria-war-and-modernity-a…

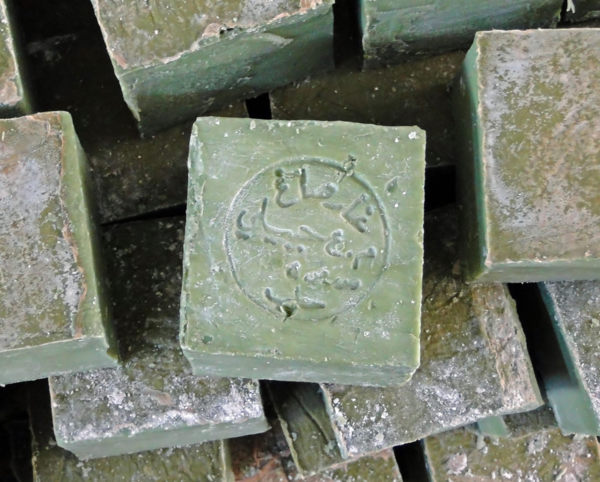

沒有任何替代品:正宗的阿勒坡肥皂帶有製造商正字標記,以及其原出產地城市的阿拉伯名。 Bernard Gagnon / CC BY-SA 3.0 當我還是個孩子時,我父親有時會帶回一整箱充滿泥土氣息的橄欖綠肥皂。表面不均勻以及蠟狀,上面寫著神祕的阿拉伯說明,當時我還不會看或了解。只想跟朋友們用一樣的肥皂:一種熟悉,機器打壓的粉紅色肥皂,香味很人工。 但我父親堅持只用阿勒坡肥皂。 他說,會洗得更乾淨,更健康。是更好的香皂。 許多年後,我父親過世,我整理他的遺物。我看到一只小皮箱,他第一次離開敘利亞到英國提的。裡頭有一團皺皺的紙包著阿勒坡肥皂,有年代了,變成深金色的。我決定來了解一下:為什麼他那麼在乎這個肥皂? 我學到的是一段歷史遺產,太優美無法私藏。我可能也及時學到,因為暴力正逐漸威脅到敘利亞的文化遺產,會把它們從地球上抹去。 敘利亞內戰持續八年。那時已經摧毀阿勒坡古老的肥皂製造業。戰亂一開始,幾乎整個行業的人力被迫逃亡,一些人到其他城市,一些人到新的國家。 今天,雖然敘利亞部分地區的戰爭肆虐,但政府部隊大部分能重新掌握阿勒坡,這座城市逐漸復甦,重回工作崗位。包含阿勒坡的傳統肥皂製造商,他們翻新店面重新恢復生產。在政府組織和慈善基金的協助下,肥皂重新成為敘利亞獲利的出口商品。

阿勒坡肥皂,在阿拉伯語是ghar,或稱為阿勒坡的肥皂Savon dAlep,受到全世界愛好者的推崇。很多歷史學家認為這是世界上第一個現代肥皂,固體,長方形,用於沐浴和個人衛生。手工製作,只含三種成分:橄欖油,月桂油和鹼液。不含動物脂肪或衍生物,不含有害化學物質或人工色素。洗後的感覺?一種強效保濕與細緻滑嫩的感覺,皮膚敏感的人,包括小嬰兒和患有濕疹,牛皮癬和長痘痘的人都很喜歡 幾千年來,月桂樹、月桂樹的葉子和漿果,一直是地中海富貴繁榮的象徵。樹葉所編織的皇冠為了加冕古希臘的精英,你在古典雕塑作品看到的,羅馬皇帝和勝利的鬥士等等。月桂樹漿果含有阿勒坡肥皂的神奇成分,有藥用特性的精油,能抗真菌,抗微生物,以及消炎等等。 雖然它的起源迷失在時間的迷霧,但阿勒坡肥皂可能從美索不達米亞平原的蘇美文化演化而來(現代敘利亞,土耳其,伊拉克和科威特)。蘇美紡織貿易商會一種皂基液體溶液,從動物油脂與木灰混製出來的。 今天,美索不達米亞幾個大城市仍存在,兩個在敘利亞。一個是大馬士革,這個擁有11000年歷史的敘利亞首都廣泛被認為是世界上最古老有人居住的城市。另一個就是阿勒坡,被認為有人居住達8000年了。

肥皂的傳承在西元100到200年之間變得更明朗,當時敘利亞是羅馬的省。正因為如此,所以首次有大型加熱浴場或熱水浴缸,以及開始了土耳其浴的傳統(今天稱為土耳其浴室)。在這些社交場合,男人會討論肥皂與保養品,一種習俗,演變出精緻肥皂的產生。 不同朝代與帝王的更迭,幾世紀過去,拜占庭,倭馬亞和奧圖曼,僅舉幾例 - 公共沐浴演變得更加精緻,更加華麗。提供給前來沐浴人使用的肥皂也變得更加繁複,打下我們今天看到的阿勒坡肥皂的基礎。 當十字軍回到歐洲,裝滿了從東方帶回的寶藏,精緻的敘利亞肥皂也普及到一般民眾。隨後,阿勒坡肥皂的產量增加,很快整合成該市的經濟。因為阿勒坡位在歷史悠久的絲路的關鍵位置上,出口很簡單。 不久,歐洲肥皂製造商就盡其所能複製這樣的商品。有名的馬賽皂與橄欖皂S就被認為是這樣的傳承。但阿勒坡香皂演變數百年的生產過程,以及嚴選敘利亞當地特有的珍貴素材則完全無法複製。

收成時間是秋天從敘利亞北邊的山區開始,當樹上的墨黑色的漿果成熟時。從十月到十二月,會由當地以此為生的婦女去採摘。收成的漿果賣到阿勒坡或大馬士革的油商,或由離家較近的收成農社加工。 一旦(漿果的)精油被蒸餾,就會與橄欖油混合,成為香皂裏頭大部分的成分。 月桂油與橄欖油比例佔越多,成品就越貴。單單一塊皂售價是4至10美元,取決於月桂油的含量。

接下來是皂化過程,一種酸與基底之間的化學反應形成鹽。在這種狀況下,小量的鹼液與油的混合物加熱,直到看到濃稠深綠色的溶液形成。將這樣的溶液倒在大型乾燥室的石頭地板上,位在每個肥皂製造廠的下面,形成一層厚厚的形同網球場的綠色地毯。 不管用哪種方法製造,整片最後都會整齊裁切成長方形,約5英寸長,4英寸寬。然後每一塊肥皂壓印製造商的標記,以及阿勒坡的阿拉伯名:Halab(حلب)一個重要的區別特徵與如假包換的正字標記。 最後是乾燥熟成。數百個香皂排成好看的垂直狀,通常是金字塔或圓頂狀,可以讓每塊香皂有充分的空間接觸空氣。然後這些皂塔放在工廠地窖數個月,溫度相對恆定 - 既不熱也不冷。香皂在整個冬季和早春熟成,然後就可以賣出去了。 在政府獲得阿勒坡的治權後,Yazan Sabouni是第一家開工的工廠。23歲的雅讚與他的兩個兄弟阿不杜拉與札爾一起經營,有百年歷史的家族企業。甚至他們的姓氏“Sabouni”在阿拉伯語代表著就是“肥皂製造商”的意思。 戰爭嚴重擾亂他們古老的傳統。「[戰爭期間]幾乎所有的肥皂製造商都離開阿勒坡,」薩布尼說。「有些人到別的城市,有些則完全離開敘利亞...... [他們的工廠和商店被拆除後]。感謝上帝,我們失去錢與房產,但命還留著。」 目前,該市正在進行修繕和整修,但完全恢復還需要一段時間。不僅建築物遭到破壞與毀損,昂貴的器材也被偷走。 結果一直是古代阿勒頗肥皂業的字面意義。「戰爭之前,有超過200個大型[肥皂製造]實驗室和工作坊,」「現在不超過20個。」另一位著名肥皂製造商塔拉勒阿尼斯說。 肥皂製造者不是唯一生計受到戰爭危害的。阿勒坡很多著名的肥皂通路商與商店,被圍在阿勒坡古老城牆之內,被聯合國教科文組織列為世界遺產。很多古城,包括Al-Madina Souq,一個市集有很多可汗與市集的地方,在2012的阿勒坡戰爭中受到嚴重的破壞。這些商人也還在恢復當中。 對於阿勒坡的很多肥皂製造商來說,這樣的傳統讓他們能迅速恢復。像剛剛提到的薩布尼與阿尼斯,都是傳承好幾代的家族事業。阿尼斯是十六歲在父親的指導下就開始經營,他不想這樣的家庭事業在他手中結束。 「我要阿勒坡香皂業在我之後還在這裡,”他說。 “為了我的家人,為了阿勒坡所有的居民,為了這個世界。」 雅讚深表同意。「這裡的人保養自己,保養他們的身體好幾千年了」他說。 「阿勒坡香皂跟法國香水,瑞士手錶或義大利麵佔有同等的份量。」 但真正的回歸是大量人工回巢,被製換掉的男人女人形成這個產業的生命線。阿尼斯蠻樂觀的,「有了支持與時間,這個產業會恢復元氣的」他說 不管在阿勒坡會發生怎樣的改變,有一樣東西絕不會被時間洪流給沖洗掉的,就是這款看來平凡低調的香皂。它的配方與故事會在阿勒坡人的手裡持續流傳下去。不管是在舊城的露天市場,還是移民的手提箱裡。

In Syria, War and Modernity Are No Match for the World’s Oldest Soap

The artisans of Aleppo keep plying their ancient trade, one bar at a time. by Nora Wallaya •August 01, 2019 Accept no substitutes: Authentic Aleppo soap bears its makers mark, and the Arabic name for the city of its origin. Bernard Gagnon / CC BY-SA 3.0 When I was a kid, my father would sometimes come home with a suitcase full of earthy-smelling olive-green soap. It was knobbly and waxy and marked with curious Arabic inscriptions that I couldn’t yet read or understand. I wanted to use the same soap my friends were using: a familiar, machine-pressed bar of pink Imperial Leather, whose fragrance mimicked the artificial perfumes in my cosmetics. But my father insisted I use only the Aleppo soap. It was a cleaner, healthier choice, he said. It was a better soap. Many years later, after my father died, I was sorting through his belongings. I came upon the small leather suitcase he brought with him to the U.K. the first time he left Syria. Inside was a scrunched paper bag filled with Aleppo soap, now aged and turned the color of deepest gold. I decided to investigate: Why did he care so much about this soap? What I learned was a historical legacy too good to keep to myself. And I may have learned it just in time, as violence is threatening to wipe Syria’s cultural heritage clean off the earth. The Syrian Civil War has been raging for eight years now. In that time it has decimated the ancient tradition of soap-making in Aleppo. Nearly the entire industry’s workforce was forced to flee when the fighting started—some to other cities, some to new countries altogether. Today, though the war rages on in parts of Syria, government forces have mostly regained control of Aleppo, and the city is slowly coming back to life—and going back to work. That includes some of Aleppo’s traditional soap-makers, who are renovating their workshops and reviving production. With help from government organizations and charitable funds, the soap is again becoming a popular and profitable Syrian export. Aleppo soap, known as ghar in Arabic, or Savon d’Alep, is revered by aficionados around the world. Many historians consider it to be the world’s first modern soap bar—solid, rectangular, and used for bathing and personal hygiene. Made by hand, it contains just three ingredients: olive oil, laurel oil, and a tincture of lye. It has no animal fats or derivatives, no harmful chemicals or artificial colors. The result? An intensely moisturizing and delicate balsam widely used by those with sensitive skin, including small babies and those who suffer from eczema, psoriasis, and acne. For thousands of years the leaves and berries of the laurel tree—Laurus nobilis—have been a symbol of wealth and prosperity in the Mediterranean. The tree’s fronds crowned the heads of ancient Greece’s powerful elite, figures in classical sculptural works, Roman emperors, and victorious gladiators. But it’s the elixir of the tree’s berries that contain the magic ingredient of Aleppo soap—an essential oil with medicinal properties shown to contain anti-fungals, anti-microbials, anti-inflammatories, and more. While its genesis is lost in the mists of time, Aleppo soap may have evolved from the Sumerian civilization of Mesopotamia (modern-day Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Kuwait). Sumerian textile traders are known to have used a saponaceous liquid solution, created from a concoction of animal fat and wood ash. Several of Mesopotamia’s great cities remain today, including two in Syria. One is Damascus, the 11,000-year-old Syrian capital widely believed to be the world’s oldest continuously inhabited city. The other is Aleppo, thought to have been continuously inhabited for 8,000 years. The soap’s lineage becomes a little clearer between the years 100 and 200, when Syria was a Roman province. It was at this point that large heated bathhouses, or thermae, first appeared in the area and kick-started the hammam bathing tradition (known today as Turkish baths). In these social settings, men compared their soaps and tonics—a practice that led to the crafting of fine soaps. As centuries passed under the rule of various empires and dynasties—Byzantine, Umayyad, and Ottoman, to name a few—the public bathing tradition became more refined, and more opulent. The soaps used by bathers became more sophisticated too, laying the groundwork for the Aleppo soap we know today. When the Crusaders returned to Europe loaded with treasures from the East, news of the fine Syrian soap they’d found reached the masses. Subsequently, soap production increased in Aleppo, and soon became integral to the city’s economy. Exporting it was simple, thanks to Aleppo’s key position along the historic Silk Road trading route. Soon European soapmakers were replicating the product as best they could. The celebrated Savon de’Marseille and Castile soap are believed by some to be two such iterations. But the Aleppo soap’s centuries-old production process, and the select precious ingredients unique to the Syrian region, cannot be fully replicated. The harvesting process begins in the fall in Syria’s mountainous north, when the inky-black berries of the tree are ripe. From October to December they’re picked by women whose livelihoods are tied to the harvest. The collected berries are then sold to oil merchants in Aleppo or Damascus, or processed closer to home by the communities that harvest them. Once the essential oil has been distilled, it’s mixed with olive oil, which comprises the vast majority of the soap’s content. The greater the ratio of laurel oil to olive oil, the more expensive the finished product. A single bar today will usually cost $4 to $10, depending on its laurel oil content. Next comes the saponification process—a chemical reaction between an acid and a base to form a salt. In this case, the oil mixture is heated with small amounts of lye until a thick, dark green solution is produced. The solution is poured onto the stone floors of large drying chambers beneath each soap factory, forming a thick carpet of green gloop the size of a tennis court.

Whichever method is used, the green sheet is neatly sliced into rectangular hunks roughly five inches long by four inches wide. Each bar of soap is then stamped with the maker’s mark, as well as the Arabic name for Aleppo: Halab (حلب)—an important distinguishing feature and stamp of authenticity. The final stage in the process is drying and curing. Hundreds of bars are arranged together into attractive vertical shapes—usually a pyramid or a dome—which allows each bar to receive maximum exposure to the air. These soap towers are then left out for months in the factory cellar, where temperatures are relatively constant—neither too hot nor too cold. The soap cures throughout the winter and early spring before it’s sold to the public. Yazan Sabouni’s factory was among the first to reopen after the government regained control in Aleppo. Together with his two brothers, Abdullah and Zaher, the 23-year-old Yazan runs a business that’s been in his family for over a century. Even their last name, “Sabouni,” means “soapmaker” in Arabic. The war has badly roiled their ancient tradition. “[During the fighting] almost all of the soap-makers left Aleppo,” says Sabouni. “Some traveled to other cities, and some left Syria altogether … [after their factories and shops were] demolished. We thank God that we just lost our money and buildings, and not our lives.” Reparations and renovations in the city are now under way, but it will take time for the industry to fully recover. Not only were buildings damaged and destroyed; costly equipment was stolen from the factories by looters. The result has been a literal decimation of the ancient Aleppo soap industry. “Before the war there were more than 200 large [soapmaking] labs and small workshops,” says Talal Anis, another prominent soapmaker. “Now there are no more than 20.” Soapmakers aren’t the only ones whose livelihoods have been imperiled by the war. Many of Aleppo’s famous soap-selling districts were within the walls of the Ancient City of Aleppo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Much of the Ancient City—including the Al-Madina Souq, a covered market that’s home to numerous khans and bazaars—suffered severe damage in the 2012 Battle of Aleppo. These merchants are still recovering as well. But for many of Aleppo’s soapmakers, preservation hinges on a speedy recovery. Like the Sabounis, the Anis family business has been passed down through generations. Talal Anis began working with soap when he was 16, under the guidance of his father. He doesn’t want to be the last generation to practice the family trade. “I want to make sure that the Aleppo soap industry is here after me,” he says. “For my family, for all residents of Aleppo, and for the world.” Yazan Sabouni agrees. “Our people have taken care of themselves and their bodies for thousands of years,” he says. “Aleppo soap is as important as French perfume, Swiss watches, or Italian pasta.” But the real recovery process begins with the full return of the workforce—the displaced men and women who, together, form the lifeblood of the industry. Anis is optimistic. “With support and time,” he says, “the industry will recover.” However much things may yet change in Aleppo, one thing that can never be washed away is the humble bar of soap. Its recipe and story will continue to be passed down through the hands of Aleppians, whether in the souks of the Old City or the suitcases of migrants.

|

|

| ( 知識學習|商業管理 ) |