字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| 2011/09/08 16:44:10瀏覽1531|回應0|推薦5 | |||||||||||||||

龔古爾這個名字與普魯斯特的關係:

那次得獎, 有些爭論.....獎項目的是新進的作家, "the best and most imaginative prose work of the year", Proust雖新進卻太老, 已經48, 因有氣喘未參戰, 不符合戰後鼓勵青年作家(對手 Roland Dorgeles 既年輕又有參戰)的精神, 還有, 書太厚......印象裡讀過, Proust去大力運作了一下關係, 如把該書獻給他的恩師, 諾貝爾獎得主, 法蘭西學院 (Academie francaise) 院士Anatole France....才撫平眾議 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prix_Goncourt Controversies Some decisions for awarding the prize have been controversial, the most famous case being the decision to award the prize in 1919 to Marcel Proust; this was met with indignation, since many in the public felt that the prize should have gone to Roland Dorgeles for Les Croix de bois, a novel about the First World War. The prize was supposed to be awarded to promising young authors, whereas Proust was 48 (Proust was a beginning author, though, which is the only eligibility requirement for the prize, age being unimportant); and, this was immediately after the end of the war, where Dorgeles had fought, whereas Proust had been deemed unfit for service for medical reasons (he had asthma).  http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_Houellebecq

2010 的《龔古爾文學獎》得主是 Michel Houellebecq 的La Carte et le territoire

******************************

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_Houellebecq

2010 的《龔古爾文學獎》得主是 Michel Houellebecq 的La Carte et le territoire

******************************

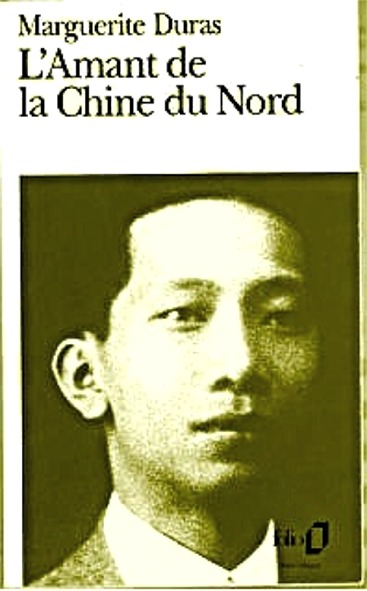

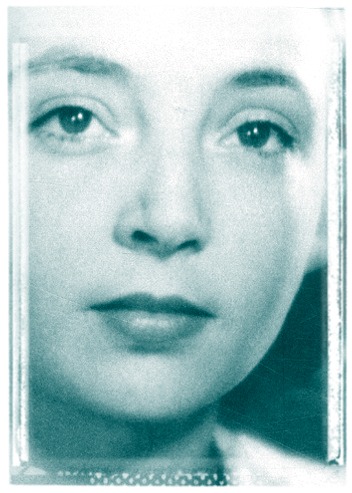

龔古爾兄弟 龔古爾兄弟,即19世紀法國作家龔古爾·德·愛德蒙(Edmond de Goncourt,1822年—1896年)和他弟弟龔古爾·德·儒勒(Jules de Goncourt,1830年—1870年)。 哥哥埃德蒙1822年5月26日生於南錫,弟弟儒勒1830年12月17日生於巴黎。1849年兩兄弟定居巴黎,一起研究法國18世紀的歷史,發表《18世紀的藝術》一書。龔古爾兄弟這兩位作家對法國自然主義小說、社會史和藝術評論都有貢獻,兩人都終身沒有結婚,他們並非孿生兄弟,且相差八歲,但他們舉止行為相似,有相同的愛好,儘管為過於神經質的敏感症所困擾(一說弟弟患有梅毒),永遠以單數龔古爾發表著作。重要作品有《翟米尼·拉賽特》、《少女艾爾莎》、《親愛的》等,龔古爾兄弟強調小說一定要反映生活,動筆之前一定進行廣泛的調查研究,人物大都實有其人,是「文獻小說」之創始人。因為兩兄弟抱持獨身主義,小說中不時流露對女人的偏見。 龔古爾兄弟的另一重要文獻是他們堅持寫作數十年、多達22卷的《龔古爾日記》,是研究法蘭西第二帝國和第三共和國時代文藝界情況的寶貴史料。弟弟儒勒1870年6月20日卒於於巴黎。1896年7月16日哥哥愛德蒙卒於尚皮尼,死後遺囑宣布將全部財產成立龔古爾學院,並設立龔古爾學會,由10位委員負責,每年從當年發表的小說中評選出最佳新人作,獎勵5000金法郎。《龔古爾文學獎》從1903年開始評選,獎金雖然不多,但獲獎者的作品保證暢銷,所以這個獎項非常受關注,每年12月學會委員聚集在巴黎德魯昂飯店進行評選,外面等候的記者雲集。 由於《追憶逝水年華》卷帙浩繁,4000多頁、200多萬字,委婉曲折,細膩至極,難讀難譯,有專家認為要先看第五卷,再回頭看第一卷。普魯斯特的弟弟羅貝爾笑著說:“要想讀《追憶逝水年華》,先得大病一場,或是把腿摔折,要不哪來那麼多時間?”當年《追憶逝水年華》第一卷出版時,許多出版社拒絕出版,《新法蘭西評論》的著名作家紀德(Andre Gide)拒絕推薦出版這部小說,奧蘭夫出版公司的阿爾費萊德·安布羅看了書稿大惑不解,“為什麼要在開頭用三十頁描寫自己睡不著覺?”因此普鲁斯特還得自掏腰包印書出版。 1913年第一部小說《在斯萬家那邊》(Du cote de chez Swann)出版,《新法蘭西評論》的主編兼詩人里維埃爾(Jacques Riviere)大力推薦,引起熱烈的討論,紀德很有風度的承認錯誤,並寫信向普魯斯特致歉。 1919年第二部小說《在少女身旁》(A l'ombre des jeunes filles en Fleurs)出版,一開始反應平平,但隨後榮獲「龔古爾文學獎」(Prix Goncourt),普魯斯特開始聲名大噪。 法國龔固爾獎是十九世紀末文壇名士愛德蒙.得.龔固爾(Ed-mond de Goncourt)為紀念其亡弟而於一九○三年設立的,以獎勵深具創意之作品為宗旨。 龔固爾的歷史悠久,名聲響亮,雖然獎金僅有50法郎,但被視為文學界至高榮譽。獲獎作品通常都會暢銷大賣,得獎作家則會成為日後重要作家,世界文壇往往可藉由龔固爾獎,窺得最新法國文學風氣和走向。 此項文學獎最主要是針對當年的出版品中,選出最具創意的小說和散文,在每年的十一月頒獎,贏得這項獎的小說在銷售時,則會紮上醒目的紅色「龔固爾獎」絲帶。 法國文豪普魯斯特(Marcel Proust)、圖尼埃(Michel Tournier)與莒哈斯(Marguerite Duras)都得過此獎。 p.s. 莒哈斯(Marguerite Duras)就是"情人"的作者.....根據"長眠在巴黎"一書作者謬詠華小姐考據, 當年莒哈斯的中國情人的真實名字, 是"黃水梨" Huynh Thuy-le (p.111)       黃水梨與莒哈絲愛情故事的西貢旅遊介紹, 下為其墓    電影"情人" 電影"情人" ******************************

歐...扯得太遠了.....sorry****************************** http://proustreader.wordpress.com/category/the-goncourt-journals/ Archive for the ‘The Goncourt Journals’ Category The Goncourt brothers may have been Proust’s favorite authors to parody, but that may be because they are such fun to read. Take these two journal entries, on the death of their beloved servant Rose. 16 August It was this woman, this admirable nurse, whose hands our dying mother put into ours. She had the keys to everything she decided and did everything for us. For as long as we could remember we had made the same old jokes about her ugliness and her ungainly body, and for twenty-five years she had given us a kiss every night. She shared everything with us, our sorrows and our joys. Hers was one of those devotions which one hopes will be there to close one’s eyes when death comes… Thursday, 21 August Yesterday I learnt things about poor Rose, only lately dead and practically still warm, which astonished me more than anything else in the whole of my life; things which completely took away my appetite, filling me with a stupefaction from which I have not yet recovered and which has left me positively dazed. All of a sudden, within a matter of minutes, I was brought face to face with an unknown, dreadful, horrible side of the poor woman’s life. Those bills she signed, those debts she left with all the tradesmen, all had an unbelievable, horrifying explanation.. She had lovers whom she paid. One of them was the son of our dairywoman, who fleeced her and for whom she furnished a room. Another was given our wine and chickens. A secret life of dreadful orgies, nights out, sensual frenzies that prompted one of her lovers to say: ‘It’s going to kill one of us, me or her!’ A passion, a sum of passions, of head, heart, and senses, in which all the unfortunate woman’s ailments played their part: consumption, making her desperate for satisfaction, hysteria, and madness. She had two children by the dairywoman’s son, one of which lived six months. When, a few years ago, she told us she was going into hospital, it was to have a child. And her love for all these men was so sickly, excessive, and overwhelming that she, who was the very soul of honesty, robbed us, yes, robbed us of a twenty-franc piece out of every hundred francs, and all in order to keep her lovers and pay for their sprees. Then, after these involuntary offences, committed in violent contradiction to her upright nature, she would sink into such despondency, such remorse, such self-reproach, that in this inferno in which she went from one lapse to another without ever finding satisfaction, she started drinking in order to escape from herself, to postpone the future, to flee the present, to sink and drown for a few hours in one of those slumbers, those torpors which used to lay her out for a whole day on a bed on to which she had collapsed while making it. And what did the unfortunate woman die of? Of having gone to Montmartre one night eight months ago, during the winter, unable to repress her curiosity, in order to spy on the dairywoman’s son, who had thrown her out; a night spent standing at a ground-floor window, trying to see who the woman was who had replaced her; a night from which she had returned soaked to the skin and mortally sick with pleurisy. Poor woman! We forgive her. Indeed, seeing something of what she must have suffered at the hands of those working-class pimps, we pity her. We are filled with a deep commiseration for her, but also with a great bitterness at this astounding revelation. Remembering our mother, who was so pure and to whom we were everything, and then thinking of Rose’s heart, which we believe belonged to us, we feel something of a disappointment at the discovery that there was great part of it which we did not occupy. Suspicion of the entire female sex has entered into our minds for the rest of our lives: a horror of the duplicity of woman’s soul, of her prodigious gift, her consummate genius for mendacity. (75-76) |

|||||||||||||||

| ( 知識學習|其他 ) | |||||||||||||||

山東文藝出版社

山東文藝出版社