這是轉貼出版人吳介禎牆上的文字,照片也是還在研議的書封,但是我耐不住虛榮(您是知道的)所以我不顧江湖道義,硬著頭皮,厚著臉皮、黑著良心就給他先貼上來炫耀。不過,我得承認,以我這破爛英文,我並沒有能力讀完讀懂,還好這是給英語系的外國人看的,而且,絕大多數的外國人(不論那個語系),中文能力應該有一半以上的人不如我。我心裡稍稍平衡些。

英文好得不得了的您,請慢慢品讀吧!據說七月要上架了!

Introduction

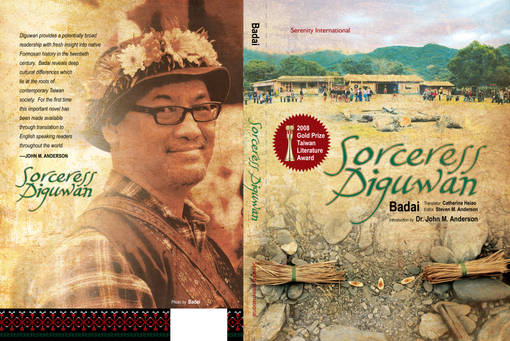

In 2007 a Chinese language version of Diguwan: The Story of Damalagaw was released by Rye Field Publications and the next year won the Taiwan Literature Award. For the first time this important novel has been made available through translation for American and other English speaking readers throughout the world.

Badai’s earlier novels introduced the Chinese speaking public in Taiwan to the history and culture of his aboriginal clan called the Damalakaw. They lived in a small village, popularly referred to as Damalagaw, located in the agriculturally rich lowlands of southeastern Taiwan. Badai’s stories made an important contribution to the Taiwan Aboriginal Cultural Renaissance movement, which was growing in influence in the very years that he published his first four books. Native writers and publishers active in this movement have tapped into the well-spring of aboriginal culture and have been deservedly celebrated by Professor Kuei-fen Chiu, at the National Chung-hsing University and other scholars.

This English translation of Diguwan provides a potentially broad readership, including an American audience, with fresh insight into native Formosan history in the twentieth century. The opening passages introduce the reader to the socio/economic life of the villagers, including their trading practices with nearby towns. The rebellious people of Naibeluk are singled out in the narrative as especially dangerous but essential to the economy of the Damalagaw. The Japanese authorities in Tatan, the provincial seat of Japanese rule, discouraged trade with the Naibeluk, especially suppressing all barter for guns and ammunition which would be used by the Damalagaw and other regional towns if they rose up in rebellion against Japanese colonial rule.

In the following chapter, the reader is caught up in dramatic events surrounding the suicide of an abused Chinese woman whose family lived on the outskirts of Damalagaw, the village featured in the narrative. A teenager named Mawaz appears as a runner on one of the safer foothill trails leading out of the village. To avoid surprising other travelers or enemy raiders Mawaz had a Dawlyu strapped to his back, whose metal clanger kept up a continuing noise as he ran. The non-melodious sound of this clanger served strickly a utilitarian purpose, lacking any musical appeal to other travelers. Custom in the province protected Dawlyu carriers from all threats. Suddenly, however, the barefoot boy stubbed his toe on a rock sticking up on the trail. Just a youth of twelve, Mawaz took his runner’s responsibility very seriously because his father named Wuguwabin was an influential village leader. So he ignored the pain in his foot and proceeded to the cemetery where a shocking encounter awaited him and triggered a crisis in the village. Badai’s handling of this scene leaves the uninitiated reader with many questions about the personalities and cultural habits of the characters involved in the events unraveling from the pivotal cemetery drama. In a sense, the cemetery scene sets the stage for the rest of the novel where the reader is introduced to a rich cast of characters, both native and Chinese, men and women, villagers and Japanese authorities. Woven into the encounters of these distinctive character, with their conflicting motivations, Badai reveals deep cultural differences which lie at the roots of contemporary Taiwan society. It is a good tale, full of complex characters. Some are cunning, some are foolish and gullable; others are saturated with magical powers pivotal to the plot development. One of these persons of magical ability is Diguwan, a village woman of such importance to the narrative that Badai named the novel after her.

Native Formosan Magic

All of Badai’s novels talk about the magic abilities of women who guard the welfare of their home villages. In one novel, Badai described how such remarkable women used their supernatural power to summon a girl living in the contemporary world to their seventeenth century village to aid them in times of stress. In Diguwan, the village sorceresses play an important role in protecting against attacks by hostile raiders who are too numerous for the men of this small Puyuma village to adequately repulse by themselves. The fifty year old heroin named Diguwan is the most naturally gifted sorceress in the community. Her name refers to a rare small bird with colorful feathers and a reputation for chattering continuously. Like her namesake, Diguwan does not hesitate to express her opinions to everyone, including the male leaders of the community who find her nagging annoying. They put up with her and her sister sorceresses because their presence is essential to the defense of the town. In crisis after crisis, these women act as guardians of the community, allowing entry only at established magical portals or gates which can be watched and easily defended against intruders. As a result, this tiny Puyuma town was never overrun by its enemies and was able to play an influential role in the politics of the TaiTong Plain where numerous agricultural communities were located. The town mayor and council were wise in the ways of diplomacy, seeking non-violent solutions to conflict rather than open warfare.

As the story develops, the reader discovers that the Japanese underestimate the Damalakau who they considered an unimportant and powerless player in provincial conflicts. They were content to rely on a barb wire fence they had built to keep hostile tribes from crossing the mountains to raid or trade on the TaiTong Plain. Sitting comfortably in Tatan, the provincial capital, these colonial authorities were satisfied with loose surveillance of the relatively peaceful Damalakau who came to Tatan regularly to trade at its large marketplace. The Tatan town council was also content with this arrangement, for it has ambitions to dominate eastern Taiwan when the Japanese left the island.

The Japanese police considered the aboriginal population of the region to be obsessed with owning guns. The natives claimed to need modern rifles for hunting, but everyone knew that they would be used for self-defense and possibly rebellion against Japanese hegemony. In this tense atmosphere, the Damalagaw town council was not contented with a strictly diplomatic program for communal survival. They did not plan to remain without rifles while the nearby agricultural towns were arming themselves. The Japanese wire fence had proven ineffective in stopping their contact with the fierce mountain towns, especially the rebellious Nibeluk. For many years, this town was surreptitiously visited by Damalagaw traders who purchased materials for making guns and ammunition.

With this background, the reader meets Mawneb, a millet farmer who is the clever gunsmith of the village. His daughter is in love with the young Dawlyu runner Mawaz who stubbed his toe in an earlier chapter. Mawaz’s father Wuguanbin was the second highest official on the town council, a cunning politician who was instrumental in protecting the gunsmith from detection by the Japanese police who were hunting for him. From this point forward, the plot focused on the actions of the men of the community and their support for Mawaz’s secret gun manufacturing. The intrigue shifts to the Tatan market where the Japanese police plot to capture Mawaz. Only the prophetic warning of Diguwan, the little sorceress, saves the situation from becoming a disaster for the whole Damalagaw community.

Misogyny

Badai weaves a subplot into this tale of intrigue over armaments and town alliances against the Japanese imperialists. It focuses on a Han Chinese family led by Ah-sui who has been accepted by the Puyuma residents of Damalagaw because of his knowledge about farming white rice. This crop was greatly favored by Japanese official who coveted it for export to Japan. The Puyuma farmed millet and brown rice, however, which brought low prices in the local markets and kept them from prospering in the colonial economy.

Unfortunately, this Chinese family brought not only knowledge of white rice farming but also traditional Han customs which subjugated women. Their patriachical traditions were deeply offensive to the matriarchal Puyuma and their neighbors. Badai’s condemnation of Chinese misogyny is woven as a polemical thread throughout the novel. He contrasts the wife beating and inferior treatment of women in An-sui’s extended family with the respect shown women in Puyama customs. And he questions the presumed superiority of Chinese islanders over the so-called ‘uncivilized’ native Formosans. The Damalagaw town council descends into crisis over these fundamentally conflicting cultural values, and only the intervention of the clever town leader named Wuguanbin prevents this Chinese family from being driven from the Puyuma controlled region.

It is in the context of this subplot featuring the dignity and human rights of women that Diguwan proves her value to the community. Though much of the main story features the actions of the men of the village, it is Diguwan whose magical skills saves the day and earns her the leading role in the tale. Badai describes Diguwan and the other town sorceresses using both white and black magic. And these women go with the men in an expedition where conflict with enemies was anticipated. Their role was to guard the scouting party from any hostile forces which might attack in the night or from ambush. Diguwan’s special expertise was with what Badai called a “sentinel spirit” [a portal guard] who protected the humans.

Bear Symbolism

After the dramatic events of the story come to a climax near the end of the narrative, Badai relates a concluding story of a boy and his father encountering a bear. The father advised his son not to try to flee from this dangerous animal, since the bear could easily outrun them. Instead they prepared to defend themselves against an attack. The moral of this incident is that in Puyuma folk lore one has to take initiative to turn a bad situation to one’s advantage. A bear encounter would not necessarily lead to their death. Instead the father saw the encounter as an opportunity to get bear meat and the honey the bear was eating.

At one level the bear in this ending represented the occupying Japanese army, which deliberately was suppressing Puyuma culture and trying to impose Shintoism and traditional Japanese customs onto the Formosans.

Thoughtful readers should consider that Badai chose the bear encounter in a broader context which included the contemporary Han Chinese dominance of Taiwan politics and cultural programming. Since the Nationalist army seized Taiwan in 1949 during its defeat by the Communist on the mainland, native civil rights have taken a back seat under Han Chinese rule. For decades, native writers simply were not published if they openly criticized the Nationalist government or featured historic conflicts between Chinese and Formosan populations. Badai’s Diguwan openly challenges these conventions. It is not only the Japanese officials who denigrate the Puyuma residents of Damalagaw as “well behaved” and passive agriculturalists, but also the humble Chinese rice farmers who also considered them inferior. As the story develops, these poor Chinese farmers discover the importance of cultural tolerance and come to accept the Puyuma who aid them in their time of need. Badai once again challenges his readers to consider issues of justice, gender equality, and survival of native culture in contemporary Taiwan.

字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大