字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2006/05/02 10:15:59瀏覽2018|回應19|推薦7 | |

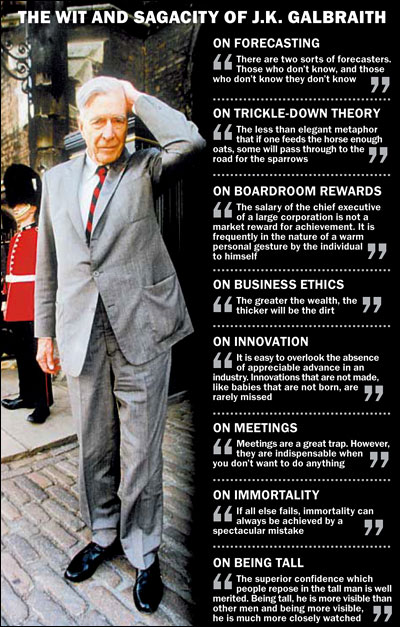

哈佛大學經濟系教授Galbraith過世(1909-2006),我登政治社會學大師Barrington Moore過世的文章乏人問津,使我對在此介紹他有點心灰意冷.不過Galbraith究竟是中譯最多的經濟學家之一(參考下列);張鐵志學長在5/2的中國時報有篇紀念他的文章,值得參看;但是他把柏克萊經濟學家deLong的名字譯成狄榮,未知是否從台語發音?deLong與其他人的網誌對紐約時報悼文稱諾貝爾獎得主貝克與Stigler"證明"廣告扮演了提供資訊而非操縱消費者"深為不滿 http://delong.typepad.com/sdj/2006/04/john_kenneth_ga.html deLong對紐約時報對他觀點的概述也不滿意,其實他的書評中提到美國白手起家,苦幹成功的個人主義迷思,乃是福利國家在美國不能成功的原因,紐時的概述並沒錯,頂多過度引申了他對西西弗斯迷思的引用.為何美國的福利國家在先進工業化國家中是最不發達的,美國的大社會何以垮台, 需要另文詳述. 我讀過Galbraith不確定的年代(The Age of Uncertainty,桂冠的翻譯不信實,杜念中的翻譯大概更好些;據英國泰晤士報報導,BBC據本書製作的13集電視節目,耗資1百萬英鎊(可是1977年的一百萬英鎊!),費時兩年半)與富裕的社會(部分). 這裡轉載紐約時報與英國金融時報的悼文 Galbraith曾任美國經濟學會會長,甘迺迪時代的美國駐印度大使,兩獲美國文人的最高榮譽總統自由勳章(1946與2002),但是遺憾未獲諾貝爾獎 出任美國駐印度大使時,他和印度總理尼赫魯建立了良好關係(雖然據說甘迺迪總統自己對印度的社會主義道路頗有戒心),但與國務院不和;中共與印度1962年發生邊境衝突時,正值古巴飛彈危機,白宮與國務院或五角大廈無暇他顧,因此Galbraith說他得以掌控局勢,確保印度獲得所需外援,並宣布美國承認印度北部邊界. 甘迺迪與詹森兩代的國務卿都是魯斯克(Dean Rusk),據Richard Reeves在他的甘迺迪傳記中說,Galbraith後來在他的小說中諷刺國務院,是遺恨於他們這些自由派學者可以管國內事務,但是碰到國際事務還是要聽Rusk這種人的話. 此外,悼文中都提及Galbraith願學Veblen;其實讀他的不確定的時代,就知道他欲居Veblen與凱因斯之間;他也的確處Veblen與凱因斯之間,不像凱因斯那樣出身顯貴(父親就是名經濟學家,母親是劍橋大學最早的畢業生之一),但又不如Veblen那樣,因為風流韻事太多,而在學界屢遭蹭蹬,得如凱因斯一樣,成為有權者的智囊,雖然絕非恭順的廷臣. John Kenneth Galbraith, 97, Dies; Economist Held a Mirror to Society http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/30/obituaries/30galbraith.html By HOLCOMB B. NOBLE and DOUGLAS MARTIN John Kenneth Galbraith, the iconoclastic economist, teacher and diplomat and an unapologetically liberal member of the political and academic establishment that he needled in prolific writings for more than half a century, died yesterday at a hospital in Mr. Galbraith lived in Mr. Galbraith was one of the most widely read authors in the history of economics; among his 33 books was "The Affluent Society" (1958), one of those rare works that forces a nation to re-examine its values. He wrote fluidly, even on complex topics, and many of his compelling phrases — among them "the affluent society," "conventional wisdom" and "countervailing power" — became part of the language. An imposing presence, lanky and angular at 6 feet 8 inches tall, Mr. Galbraith was consulted frequently by national leaders, and he gave advice freely, though it may have been ignored as often as it was taken. Mr. Galbraith clearly preferred taking issue with the conventional wisdom he distrusted. He strived to change the very texture of the national conversation about power and its nature in the modern world by explaining how the planning of giant corporations superseded market mechanisms. His sweeping ideas, which might have gained even greater traction had he developed disciples willing and able to prove them with mathematical models, came to strike some as almost quaint in today's harsh, interconnected world where corporations devour one another. "The distinctiveness of his contribution appears to be slipping from view," Stephen P. Dunn wrote in The Journal of Post-Keynesian Economics in 2002. Mr. Galbraith, a revered lecturer for generations of Harvard students, nonetheless always commanded attention. Robert Lekachman, a liberal economist who shared many of Mr. Galbraith's views on an affluent society that they both thought not generous enough to its poor or sufficiently attendant to its public needs, once described the quality of his discourse as "witty, supple, eloquent, and edged with that sheen of malice which the fallen sons of Adam always find attractive when it is directed at targets other than themselves." From the 1930's to the 1990's, Mr. Galbraith helped define the terms of the national political debate, influencing the direction of the Democratic Party and the thinking of its leaders. He tutored Adlai E. Stevenson, the Democratic nominee for president in 1952 and 1956, on Keynesian economics. He advised President John F. Kennedy (often over lobster stew at the Locke-Ober restaurant in their beloved Though he eventually broke with President Lyndon B. Johnson over the war in In the course of his long career, he undertook a number of government assignments, including the organization of price controls in World War II and speechwriting for Franklin D. Roosevelt, Kennedy and Johnson. He drew on his experiences in government to write three satirical novels. One in 1968, "The Triumph," a best seller, was an assault on the State Department's slapstick attempts to assist a mythical banana republic, Puerto Santos. In 1990, he took on the Harvard economics department with "A Tenured Professor," ridiculing, among others, a certain outspoken character who bore no small resemblance to himself. At his death Mr. Galbraith was the Paul M. Warburg emeritus professor of economics at Harvard, where he had taught for most of his career. A popular lecturer, he treated economics as an aspect of society and culture rather than as an arcane discipline of numbers. Keeping It Simple Mr. Galbraith was admired, envied and sometimes scorned for his eloquence and wit and his ability to make complicated, dry issues understandable to any educated reader. He enjoyed his international reputation as a slayer of sacred cows and a maverick among economists whose pronouncements became known as "classic Galbraithian heresies." But other economists, even many of his fellow liberals, did not generally share his views on production and consumption, and he was not regarded by his peers as among the top-ranked theorists and scholars. Such criticism did not sit well with Mr. Galbraith, a man no one ever called modest, and he would respond that his critics had rightly recognized that his ideas were "deeply subversive of the established orthodoxy." "As a matter of vested interest, if not of truth," he added, "they were compelled to resist." He once said, "Economists are economical, among other things, of ideas; most make those of their graduate days last a lifetime." Nearly 40 years after writing "The Affluent Society," Mr. Galbraith updated it in 1996 as "The Good Society." In it, he said that his earlier concerns had only worsened: that if anything, Mr. Galbraith gave broad thought to how Mr. Galbraith argued that technology mandated long-term contracts to diminish high-stakes uncertainty. He said companies used advertising to induce consumers to buy things they had never dreamed they needed. Other economists, like Gary S. Becker and George J. Stigler, both Nobel Prize winners, countered with proofs showing that advertising is essentially informative rather than manipulative. Many viewed Mr. Galbraith as the leading scion of the American institutionalist school of economics, commonly associated with Thorstein Veblen and his idea of "conspicuous consumption." This school deplored the universal pretensions of economic theory, and stressed the importance of historical and social factors in shaping "economic laws." Some, therefore, said Mr. Galbraith might best be called an "economic sociologist." This view was reinforced by Mr. Galbraith's nontechnical phrasing, called glibness by the envious and antagonistic. Mr. Galbraith's pride in following in the tradition of Veblen was challenged by the emergence of what came to be called the new institutionalist school. This approach, associated with the Some suggested that Mr. Galbraith's liberalism crippled his influence. In a review of "John Kenneth Galbraith: His Life, His Politics, His Economics" by Richard Parker (Farrar, 2005), J. Bradford DeLong wrote in Foreign Affairs that Mr. Galbraith's lifelong sermon of social democracy was destined to fail in a land of "rugged individualism." He compared Mr. Galbraith to Sisyphus, endlessly pushing the same rock up a hill that always turns out to be too steep. Amartya Sen, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, maintains that Mr. Galbraith not only reached but also defined the summit of his field. In the 2000 commencement address at Harvard, Mr. Parker's book recounts, Mr. Sen said the influence of "The Affluent Society" was so pervasive that its many piercing insights were taken for granted. "It's like reading 'Hamlet' and deciding it's full of quotations," he said. John Kenneth Galbraith was born His father was a farmer and schoolteacher, the head of a farm-cooperative insurance company, an organizer of the township telephone company, and a town and county auditor. His mother, whom he described as beautiful but decidedly firm, died when he was 14. The Farming Life Mr. Galbraith said in his memoir "A Life in Our Times" (1981) that no one could understand farming without knowing two things about it: a farmer's sense of inferiority and his appreciation of manual labor. His own sense of inferiority, he said, was coupled with his belief that the Galbraith clan was more intelligent, knowledgeable and affluent than its neighbors. "My legacy was the inherent insecurity of the farm-reared boy in combination with the aggressive feeling that I owed to all I encountered to make them better informed," he said. Mr. Galbraith said he inherited his liberalism, his interest in politics and his wit from his father. When he was about 8, he once recalled, he would join his father at political rallies. At one event, he wrote in his 1964 memoir "The Scotch," his father mounted a large pile of manure to address the crowd. "He apologized with ill-concealed sincerity for speaking from the Tory platform," Mr. Galbraith related. "The effect on this agrarian audience was electric. Afterward I congratulated him on the brilliance of the sally. He said, 'It was good but it didn't change any votes.' " At age 18 he enrolled at A major influence on him was the caustic social commentary he found in Veblen's "Theory of the Leisure Class." Mr. Galbraith called Veblen one of American history's most astute social scientists, but also acknowledged that he tended to be overcritical. "I've thought to resist this tendency," Mr. Galbraith said, "but in other respects Veblen's influence on me has lasted long. One of my greatest pleasures in my writing has come from the thought that perhaps my work might annoy someone of comfortably pretentious position. Then comes the realization that such people rarely read." While at Keynesianism gave economic validation to what President Roosevelt was doing, Mr. Galbraith thought, and he resolved in 1937 "to go to the temple" — Cambridge University — on a fellowship grant for a year of study with the disciples of Lord Keynes. In 1937 Mr. Galbraith married Catherine Merriam Atwater, the daughter of a prominent In addition to his wife and his son J. Alan, of Washington, a lawyer, he is survived by two other sons, Peter, a former United States ambassador to Croatia and a senior fellow at the Center for Arms Control and Nonproliferation in Washington, and James, an economist at the University of Texas; a sister, Catherine Denholm of Toronto; and six grandchildren. Mr. Galbraith became an American citizen, and taught economics at Princeton in 1939. But after the fall of He was forced to resign in 1943 and was rejected by the Army as too tall when he sought to enlist. He then held a variety of government and private jobs, including director of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey in 1945, director of the Office of Economic Security Policy in the State Department in 1946, and a member of the board of editors of Fortune magazine from 1943 to 1948. It was at Fortune, he said, that he became addicted to writing. In 1949 he returned to Harvard as a professor of economics; his lectures were delivered before standing-room-only audiences. And he began to write with intensity, rising early and writing at least two or three hours a day, before his normally full schedule of other duties began, for most of the rest of his life. He completed two books in 1952, "American Capitalism: The Concept of Countervailing Power" and "A Theory of Price Control." In "American Capitalism," he set out to debunk myths about the free market economy and explore concentrations of economic power. He described the pressures that corporations and unions exerted on each other for increased profits and increased wages, and said these countervailing forces kept those giant groups in equilibrium and the nation's economy prosperous and stable. In his 1981 memoir, he said that though the basic idea was still sound, he had been "a bit carried away" by his notion of countervailing power. "I made it far more inevitable and rather more equalizing than, in practice, it ever is," he wrote, adding that often it does not emerge, with the result that "numerous groups — the ghetto young, the rural poor, textile workers, many consumers — remain weak or helpless." He summarized the lessons of his days at the Office of Price Administration in "A Theory of Price Control," later calling it the best book he ever wrote. He said: "The only difficulty is that five people read it. Maybe 10. I made up my mind that I would never again place myself at the mercy of the technical economists who had the enormous power to ignore what I had written. I set out to involve a larger community." He wrote two more major books in the 50's dealing with economics, but both were aimed at a large general audience. Both were best sellers. In "The Great Crash 1929," he rattled the complacent, recalled the mistakes of an earlier day and suggested that some were being repeated as the book appeared, in 1955. Mr. Galbraith testified at a Senate hearing and said that another crash was inevitable. The stock market dropped sharply that day, and he was widely blamed. "The Affluent Society" appeared in 1958, making Mr. Galbraith known around the world. In it, he depicted a consumer culture gone wild, rich in goods but poor in the social services that make for community. He argued that Anticipating the environmental movement by nearly a decade, he asked, "Is the added production or the added efficiency in production worth its effect on ambient air, water and space — the countryside?" Mr. Galbraith called for a change in values that would shun the seductions of advertising and champion clean air, good housing and aid for the arts. Later, in "The New Industrial State" (1967), he tried to trace the shift of power from the landed aristocracy through the great industrialists to the technical and managerial experts of modern corporations. He called for a new class of intellectuals and professionals to determine policy. While critics, as usual, praised his ability to write compellingly, they also continued to complain that he oversimplified economic matters and either ignored or failed to keep up with corporate changes. Mr. Galbraith conceded some errors and revised his book in 1971. A Move Into Politics One of his early readers was Adlai Stevenson, the governor of Although Mr. Galbraith did not at first regard Kennedy, a former student of his at Harvard, as a serious member of Congress, he began to change his view after Kennedy was elected to the Senate in 1952 and began calling him for advice. The senator's conversations became increasingly wide-ranging and well informed, Mr. Galbraith said, and his respect and affection grew. After Mr. Kennedy won the presidency in 1960, he appointed Mr. Galbraith the He said in his memoir: "Kennedy, I always believed, was pleased to have me in his administration, but at a suitable distance such as in India." Mr. Galbraith was fascinated with India; he had spent a year there in 1956 advising its government and was eager to return. He spent 27 months as ambassador, clashed with the State Department and was more favorably regarded as a diplomat by those outside the government. He fought for increased American military and economic aid for India and acted as a sort of informal adviser to the Indian government on economic policy. Known by his staff as "the Great Mogul," he achieved an excellent rapport with Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and other senior officials in the Indian government. When India became embroiled in a border war with China in the Himalayas in 1962, Ambassador Galbraith effectively took charge of both the American military and the diplomatic response during what was a brief but potentially explosive crisis. He saw to it that India received restrained American help and took it upon himself to announce that the United States recognized India's disputed northern borders. The reason he had so much control over the American response, he said, was that the border fighting occurred during the far more consequential Cuban missile crisis, and no one at the highest levels at the White House, the State Department or the Pentagon was readily responding to his cables. Mr. Galbraith published "Ambassador's Journal: A Personal Account of the Kennedy Years," a book based on the diary he kept during his time in India, in 1969. A year earlier he published "Indian Painting: The Scenes, Themes and Legends," which he wrote with Mohinder Singh Randhawa. An avid champion of Indian art, he donated much of his collection to the Harvard University Art Museums. In 1963, Mr. Galbraith added fiction to his repertory for the first time with "The McLandress Dimension," a novel he wrote under the pseudonym Mark Epernay. After Kennedy was assassinated, Mr. Galbraith served as an adviser to President Johnson, meeting with him often at the White House or on trips to the president's ranch in The relationship between the two men soon broke apart over their differences over the war in Vietnam. Nevertheless, when Adlai Stevenson died in 1965, the ambassadorship to the United Nations became vacant, and word reached Mr. Galbraith that the president was considering him as Mr. Stevenson's successor. A Job Declined Not wanting to be placed in the position of having to defend administration positions he strongly opposed, Mr. Galbraith suggested Justice Arthur J. Goldberg of the Supreme Court. The president named Mr. Goldberg, and Mr. Galbraith later blamed himself for a "poisonous" mistake that "cost the court a good and liberal jurist." Others said he took too much credit for what happened. In 1973 he published "Economics and the Public Purpose," in which he sought to extend the planning system already used by the industrial core of the economy to the market economy, to small-business owners and to entrepreneurs. Mr. Galbraith called for a "new socialism," with more steeply progressive taxes; public support of the arts; public ownership of housing, medical and transportation facilities; and the conversion of some corporations and military contractors into public corporations. He continued to rise early and, despite the seeming effortlessness of his prose, revised each day's work at least five times. "It was usually on about the fourth day that I put in that note of spontaneity for which I am known," he said. He served as president of the American Economic Association, the profession's highest honor, and was elected to membership in the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He continued to pour out magazine articles, book reviews, op-ed essays, letters to editors; he lectured everywhere, sometimes debating William F. Buckley Jr., his friend and Gstaad skiing partner. He was so prolific that Art Buchwald, the humorist, once introduced him by citing his literary production: "Since 1959 alone, he has written 12 books, 135 articles, 61 book reviews, 16 book introductions, 312 book blurbs and 105,876 letters to The New York Times, of which all but 3 have been printed." In 1977 he wrote and narrated "The Age of Uncertainty," a 13-part television series surveying 200 years of economic theory and practice. In 1990 he wrote "A Tenured Professor," about a Harvard professor who devised a legal, foolproof and computer-assisted system for playing the stock market and used his billions of dollars in profits on programs for education and peace — only to be investigated by Congress for un-American activities and forced to shut down his operations. In 1996, as Mr. Galbraith approached his 90th year, he wrote "The Good Society." Matthew Miller wrote in The New York Times Book Review, "We're not likely to find as elegant a little restatement of the liberal creed, or its call to conscience." Mr. Galbraith said Republicans out to roll back the welfare state made a fundamental error in thinking that politicians and their actions drive history. In fact, he argued, it is the reverse. Liberals did not create big government; history did. Mr. Galbraith, who received the Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton in 2000, continued to make his views known. Some were surprising, like his speech in 1999 praising Johnson's presidency, which he had helped to bring down by working with McCarthy. There always seemed to be one more book. One, "The Essential Galbraith" (2001), was a collection of essays and excerpts that a reviewer in Business Week said remained very timely. Another, "Name-Dropping from F.D.R. On" (1999), recounted encounters with the powerful, including President Kennedy's response when Mr. Galbraith complained that an article in The New York Times had described him as arrogant. Kennedy retorted that he didn't see why it shouldn't: "Everybody else does." In 2004, Mr. Galbraith, who was then 95, published "The Economics of Innocent Fraud," a short book that questioned much of the standard economic wisdom by questioning the ability of markets to regulate themselves, the usefulness of monetary policy and the effectiveness of corporate governance. He remained optimistic about the ability of government to improve the lot of the less fortunate. "Let there be a coalition of the concerned," he urged. "The affluent would still be affluent, the comfortable still comfortable, but the poor would be part of the political system." Prolific polemicist who revealed the human face of money and power OBITUARY JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH. (THE AMERICAS & INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY)(Obituary) Stephanie Flanders. The Financial Times, Asked to name an economist, many Americans over the age of 30 would think of John Kenneth Galbraith, who has died at the age of 97. But he was both somewhat less and much more than a professional economist: he was an institution of postwar "After visiting Liberal activists who believed, with Galbraith, that economies neither could nor should be left to an invisible hand lost almost every major political battle of the 1970s and 1980s. Yet while the triumph of free-market economics took his ideas further from the political mainstream, they did not make them irrelevant. Indeed, many of the dangers of untrammelled markets he had described in the 1950s and 1960s, not least the coexistence of "private opulence and public squalor", seem rather more obvious in George W. Bush's America than they had been in Eisenhower's or Kennedy's. The return of an income distribution that looks increasingly similar to that of a century ago must make his work increasingly relevant. Galbraith's persistent criticisms of Ronald Reagan's (and Margaret Thatcher's) policies culminated in the publication, in 1992, of a surprisingly influential book, The Culture of Contentment. It described how the emergence of a contented, voting majority in the In many ways, however, the 1992 book was a follow-up to an earlier, far more influential, polemic, The Affluent Society, published in 1958. No other academic title of that era, (with the exception, perhaps, of the sociologist, David Reisman's The Lonely Crowd) moved so effortlessly on to the bestseller lists, or had such a lasting impact on contemporary debate. Today it is largely remembered for introducing phrases such as "the conventional wisdom", or "the bland leading the bland" into common circulation. Yet it is important to stress the novelty of some of the underlying ideas. Few had spoken before of a "consumer society", or worried about the implications of structuring an economy solely round consumption. These days, the notion that more may not always be better for the environment, or for the balance between private and public goods, is commonplace. Time has been less kind to some of his other books: The New Industrial State, for example, a paean to economic planning by government and large-scale corporations, written in 1967, became outdated in the turbulent 1970s and 1980s. But at least two of his historical books, The Great Crash, a layman's guide to the stock market crash of 1929, and his later short compendium of booms and busts throughout history, A Short History of Financial Euphoria, published in 1990, have become classics of the genre, admired by readers on all sides of the political divide. Both works exemplified an abiding feature of Galbraith's writings: a fascination with the power of conventional ideas, especially economic ones (or mass lunacy, in the case of financial booms). Born in 1908 in Iona Station, a Scottish farming community of 23 souls in Ontario, Galbraith began his academic career inauspiciously, studying animal husbandry and soil management at Ontario Agricultural College in a lonely town called Guelph. After graduating in 1931, he went on to complete a PhD in agricultural economics at the When Galbraith went to He moved on to the American Office of Price Administration, where he ran the war-time system of price controls. Later, critics often claimed that he had deduced false lessons from this experience about the efficiency of government planning. At the time, however, the controls were deemed to have been very successful. His spell at the AOPA and, later, at the State Department running both the Strategic Bombing Survey and Office of Economic Security earned him both the Medal of Freedom and the President's Certificate of Merit. It was after running Kennedy's successful 1960 campaign that Galbraith spent a controversial time in After Kennedy's death, Galbraith remained in the Johnson administration, before resigning over Galbraith was not a modest man: he did not suffer fools gladly, and, at 6ft 8 1/2, was able to make those who did not measure up feel very small indeed. But it is fair to say that he was always more concerned with the role of economists and economic ideas in the world than with his own place in economics. Galbraith often berated his academic colleagues for not perceiving how mainstream economic instruction both concealed and supported the "real" forces guiding economic and social affairs. "All economic history, including Galbraith himself, has been the expression of vested interest." His own vested interest is best illustrated by the quotation from the 19th century economist, Alfred Marshall, with which he introduced The Affluent Society: that "the economist, like everyone else, must concern himself with the ultimate aims of man". "Economics is not a science," he argued in a 1987 book, but a "continuing interpretation of current circumstances. All its useful propositions can be stated in clear, unembellished and generally agreeable English". Galbraith's numerous books tended to be all these things; and, even rarer in economic writing, they were funny. The first line of The Affluent Society is typical: "wealth is not without its advantages and the case to the contrary, although it has often been made, has never proved widely persuasive." Though his influence waned in later years, Galbraith's "fatal fluency", as he called it, and wry sense of humour ensured that people would pay attention to what he said, even if they seldom paid heed. Galbraith was formidably productive, continuing to write articles and books into his mid-90s; The Economics of Innocent Fraud appeared in 2004. People also continued to read what he wrote. Of his contributions to American public life over the years, his rare urge, and even rarer ability, to make important economic ideas both comprehensible and amusing will be most missed.

|

|

| ( 知識學習|隨堂筆記 ) |