字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2019/10/27 22:39:11瀏覽93|回應0|推薦0 | |

這篇是指從2009年以來,北朝鮮的金正日國家主席發動先軍政治的「軍民同行」,也就是藉由成功試射飛彈造成國威的宣揚,而且確立其人民民主主義思想的器物上的鞏固。在金正日過世後,金正恩上台沒有中斷技術的研究,在頭半年被可是對内並沒有解決貧窮問題,也沒有和政治進步有直接的關連,而對外片面取消六方會談,和美日交惡,又沒有傳統盟邦中國的支持。 筆者曾經當時和北京中央當時,聯想過高句麗的問題,在隋煬帝時,隋朝大軍曾經三征高句麗,第一次親征時,隋朝的大軍和高句麗的人口總數相當,但獲得慘敗。換到現在的時空,雖然北京和平壤同為馬克斯主義的兄弟之邦,但是經濟政策上和對於政治市場關係的操作型定義,跟地緣政治的大國政治外交現實,使中國和北朝鮮在隨後的五年又有了分歧。

North Korea’s nuclear testAre you listening, America?Feb 12th 2013, 9:01 by D.T. and H.T. | SEOUL and TOKYO

EARS shut to the impending chorus of international condemnation, North Korea conducted its third nuclear test on February 12th. It said the detonation was of a “smaller and light” atomic bomb that was different from its previous two, and that it had “great explosive power”. Figuratively speaking, the blast may have been meant to resonate loudest in Washington, DC.

Judging by the seismic activity that was detected near North Korea’s Punggye-ri testing site, experts said the blast may have been marginally more powerful than that created by previous tests, in October 2006 and May 2009. Data from the U.S. Geological Survey put the tremor at a magnitude of 4.9, bigger than either of those caused previously. South Korean officials said it may have been 6,000-7,000 tons in TNT equivalent—again, bigger than in the past.

But it is not so much the blast’s brute power as the words “smaller and light” that are most worrying. That is because international analysts suspect that the North is testing a bomb sufficiently miniaturised to fit on its recently launched Unha-3 rocket, which successfully put a satellite into orbit in December. If the bosses in Pyongyang can master the critical skills required to direct a re-entry, the boffins say it is possible that such a rocket could be used to deliver a small nuclear warhead to the United States.

In coming days and weeks technical experts will be trying to analyse what fissile material was used. There was no hard evidence provided in North Korea’s confirmation of the blast. They did boast of having developed a “diversified” programme, which may suggest North Korea has now tested highly enriched uranium, as well as plutonium. The test would have taken place in a sealed tunnel in a mountainside, so it may well prove impossible to tell which material was used (in 2006, evidence of plutonium is said to have escaped; in 2009 there was no conclusive leakage). Any suggestion that it is enriched uranium fuelled the blast will add to the concerns. James Acton of the Washington, DC-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace wrote recently that North Korea’s uranium programme may enable it to build a significantly bigger arsenal than it was thought to have, which could explain why it would have been used in the third test.

In its announcement, KCNA, the North Korean news agency, said that the test was a reaction against American hostility, especially in response to the December satellite launch. Narushige Michishita of the Tokyo-based National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies reckons that the primary aim of the nuclear test was to bring America back to bargaining talks with North Korea. He said the timing may be aimed at catching the attention of a new Obama administration. It also occurred just before South Korea’s president-elect, Park Geun-hye, is due to take office, on February 25th. Mr Michishita surmises the test’s timing might make it easier for her to shrug it off in the long term.

But he acknowledged that in the short run North Korea’s relations with most foreign nations will freeze up. Ms Park was swift to condemn the test. China, which has long been North Korea’s strongest ally, had already issued not-so-veiled warnings to the North against conducting it.

The North Korean regime appears to be regularly underestimating the strength of international feeling against its nuclear programme. If North Koreas apoplectic reaction was any gauge, the strong condemnation its December rocket launch drew from the UN Security Council (UNSC) caught it by surprise. The UNSC is scheduled to discuss the regime’s latest antics early on February 12th in New York. South Korea’s foreign minister, Kim Sung-hwan, and America’s new secretary of state, John Kerry, had agreed beforehand to take "swift and unified" action in the event of another nuclear test.

The trouble is, the outside world has almost run out of the normal options for curbing the North’s nuclear ambitions: there are not many more sanctions it can impose. As our cover leader argued this week, efforts to stop the nuclear programme have “pretty much failed”. Kim Jong Un, North Korea’s fledgling dynast, is unlikely ever to give up his nuclear-weapons programme so long as it remains as his only claim to influence.

Instead, we argue for a new approach: one that seeks to undermine the regime by bombarding its people with information from the outside world, and encourages an emerging class of termite capitalists who are rooting their way through its underground black markets. They are gradually becoming a rival source of power to the regime, albeit only an economic power.

If this blast once again tests China’s patience with the rogue regime, and forces it to scale back its economic support for the Kim dynasty, perhaps that would be its one positive outcome. (Picture credit: AFP) 筆者是這樣回覆的:

Are you listening, America? Feb 20th 2013, 07:56

Reading this analysis, I don’t agree some points of view, especially the last sentences referring to you Economist’s so-called pale “nothing at all” to seriously offensive nuke test. It seems to say the fatalism is very surely predictable if Pyongyang and Washington D.C. mutually continue to play another drama while taking turn to process their respective interest-first programme of big game.

Following common sense, the Economist means this kind of fallacy, just like crying baby for candy, happens again. And once again, the sayings for the past week inferred the aberration-inclined situation which has reached the astringency when Lee Hyun-joo, a little pretty presenter, recited a sheet of report on KBS1’s primetime “News 9” or “News Plaza”.

Soon after United Nation denounced North Korean nuke test, a series of satellite photo unveiled indicating the potential wide range of conflict. US, Japan and South Korea accord the nuclear-detached stance to defensive affairs of Korean Peninsula. For the first time, contrary to Sino-North Korean treaty of friendship, China agreed the resolution imposed by UN on the sanctions against the nuclear weapon test. On the chain of East-Asian islets, China stands at the weaker position while US has spent more than 1 year reorganizing the military plan in Pacific Ocean.

I have advised Li Ke-qiang, China’s next prime minister, on Korean Peninsula affairs, which is one of big issue for China’s future by 2030. Owing to my relationship with Pyongyang regime’s Kim family, I try to keep the essential of the livings and sometimes give some should and shouldn’t. I don’t think Pyongyang’s behavior in 2006 and 2009 related to nuclear test but continental ballistic missile. Generally, the late Kim Jeon-Il exercised military-first politics which took high risk of maintenance. The policy, basically, has easily Pyongyang be transformed into Goguryeo, a kingdom making Sui and Tang dynasty headache after Han people recovered from nomadic rulers. Anyway, the obedience to international law still be highlighted, including the nuclear-registered system under UN and 5-member permanent security meeting. I feel free to Daepodong missile, but now I have few idea of the earthquake by nuclear bomb test except for that round meeting.

On Jan. 25, Nikkei newspaper reported a question of the impact on North Korea, saying both China and America affects fewer after Kim Jeon-Un’s announcement of nuke test. It is indeed sorrowful to see the stagnant six-party meeting that China chairs due to the incumbent Kim reluctant to refrain from nuclear expansion. Just one day after Xi Jin-ping, Chinese Communist Party’s secretary, met South Korean incumbent president Park Geun-hye’s envoy reaching an accordance, Kim showed a massive nuclear weapon, slightly with HTC mobile phone. Interestingly, facing the embarrassment, Xi seems to take approach of two-faced diplomatic strategy to balance national interest and the global view. I feel a bit relief from the worst guess to the better situation, although there is tension in Korean Peninsula at presence still more serious than the previous in 2006 and 2009.

Since Zhang Zhi-jun, China’s Vice Foreign Minister in celebration of Park’s win in the election on Jan. 10, was asked for the assistance of inter-Korean affairs, Ms. Park put forward the curiousity of China’s attitude toward both capitals for several times as the reference of diplomatic and military vision, besides the ally with Japan and US. Of course, Ms. Park needs more hands of friendship with keeping “Ari-rang” style in Asia, when I first heard this from Beijing’s elder governing Politburo. As NHK World reported today, the head of the Japanese Foreign Ministrys Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau, Shinsuke Sugiyama, plans to make the request to Chinas special envoy on Korean Peninsular issues, Wu Da-wei. Wu and Dai Bing-guo, the precursor managing six-party meeting since 2005, both demanded the necessary instant messaging to North Korea of the peaceful process.

With Ono Lisa’s album “Asia”, South Korea strengthened the military tie in cooperation with America, also seeking the balance between stronger won in terms of finance and the weaker economy while walking to the gate of free trade with Japan, US and China. Ms. Park may as well keep conservative attitude toward political speaking, in a recently hard-edged time, unlike her autocratic father who created “Han-river” miracle of fast-growing economy. Now she succeeds this fourth-largest economy in Asia, moreover spreading a “hermit” cultivated nation into Asian nation while living next to an nearly-isolated state. Should nuke test continue, the war may break out like the sayings several days ago by the incumbent Kim who is nevertheless the cause of the potential conflict.

Recommended 5 Report Permalink 以下是三篇和北朝鮮平壤有關的經濟學者編輯的正文,其中2月8日發文「Beiefing: North Korea - Rumbling from below」更是一篇長篇好文,就筆者所知,曾影響到當年美國國會共和黨黨團對於平壤的評價

North Korean sanctionsNuclear reactionJan 24th 2013, 8:28 by H.T. | TOKYO

SOUTH KOREAN officials believe that when North Korea next conducts a nuclear test, it will be a small one. That is nothing to be reassured about. The test, they reckon, will be aimed at creating a nuclear device small enough to fit on the tip of the 100kg satellite-bearing rocket that it launched into orbit in December. That, when North Korea masters re-entry technology, could eventually be aimed at the United States.

On January 24th, the threat of a test became all the more ominous when North Korea reacted vehemently to a UN Security Council resolution two days earlier stiffening sanctions against the regime over its rocket launch. In an unusually explicit declaration of its hostile intent carried by the state Korean Central News Agency, it said it would carry out another nuclear test as part of an “all-out action” targeted at America.

Such a test would seriously undermine the hopes of the Obama administration and incoming South Korean President Park Geun-hye for more engagement with North Korea under its young new leader, Kim Jong Un. The UNSC resolution, which extends asset freezes and travel bans, promises further “significant action” if Pyongyang conducts a nuclear test, or launches another rocket.

That sets the stage for a new round of heightened tensions in the region. It would show that yet again the North Korean regime is prepared to flout international rules, even though by doing so it materially affects the livelihood of its people. The more tension there is, the less food and other aid goes into the north. But Pyongyang may have calculated, partly based on past experience, that even if a nuclear test is met with strong international condemnation, it may still be able to re-engage with the outside world when the dust settles.

So far, North Korea has been able to bypass some of the economic impact of sanctions through mushrooming trade with China, which was initially unwilling to support the UNSC resolution, according to diplomatic sources. It was not immediately clear why China changed its mind to back the increased sanctions. But it would be helpful if it issued a warning against the consequence of a nuclear test as loudly as other nearby countries will, and strived to use the economic lifeline it provides to the north to enhance its leverage.

China and North KoreaOn the naughty stepChina continues to fret over its troublesome neighbourFeb 2nd 2013 | BEIJING |From the print edition

LIKE an indulgent parent forgiving of the most petulant of childish tantrums, China usually cuts North Korea a lot of slack. So when China on January 22nd signed on to United Nations Security Council Resolution 2087, tightening sanctions on North Korea to punish it for a rocket launch in December, its ally was surprised and outraged. Without naming China, a North Korean statement accused it of “abandoning without hesitation even elementary principles”. By the same token, the outside world saw an encouraging sign: perhaps China will at last take serious steps to rein in its pugnacious neighbour’s efforts to build a nuclear arsenal.

That is probably too much to hope. But on North Korea, China might for a while be more aligned than recently with America, Japan and South Korea. China has insisted that its main interest is in regional stability. If so, with North Korea reacting to the UN resolution by threatening to attack South Korea and stage its third test of a nuclear bomb and by vowing never to abandon its nuclear programme, it is hard not to see the country’s regime as a threat.

In this section · On the naughty step · Own goal Moreover,Global Times, a Chinese newspaper owned by the Communist Party, chided North Korea for its ungrateful reaction to the efforts China had made to soften the UN resolution, and warned it that if it “engages in further nuclear tests, China will not hesitate to reduce its assistance”. Since North Korea relies on China for fuel and food, that is a potent threat.

Now, more than ever, China might want to seem a contributor to regional peace. Its belligerence over the disputed Senkaku or Diaoyu islands has brought relations with Japan to their worst level since 1945, with China now considering Japan’s proposal for a summit between its prime minister, Shinzo Abe, and the Communist Party leader, Xi Jinping. China’s assertion of territorial claims in the South China Sea has soured relations there, too. The Philippines has been provoked into asking a UN tribunal to rule on whether part of China’s claim has a legal basis.

On both those issues China will find it hard to offer concessions. This week Mr Xi growled that “no country should presume that we will engage in trade involving our core interests or that we will swallow the ‘bitter fruit’ of harming our sovereignty, security or development.”

North Korea offers a chance for China to seem flexible without jeopardising any “core interests” and, indeed, to enhance its own security at the same time. The new treatment of North Korea could also strengthen China’s relations with South Korea, which were damaged by the failure to join the widespread international condemnation of the North for attacks on the South in 2010. And it would offer what Zhu Feng, a scholar at Peking University, calls “a new platform for China and the United States to get closer”.

But Mr Zhu also says China will not want to “corner” North Korea. At a conference in Seoul in December, Teng Jianqun, of the China Institute of International Studies in Beijing, said there were three views about policy on North Korea: that it is a troublemaker which China should abandon and treat as a security problem; that it is nothing to do with China and should be left alone; and that it is an old ally deserving of China’s full support.

Yet the consensus is that China’s prime interest is stability. The survival of the Kim dynasty ruling North Korea now seems bound up with its nuclear programme. So China may think that stepping up efforts to shut that down would not be in its interest. Certainly many Chinese scholars and, presumably, officials feel exasperated with North Korea and rather embarrassed by its antics. But China fears that collapse of the regime might lead to unrest, refugees crossing into China and the presence of American forces on the other side of China’s own borders. That would be even worse.

Plenty of voices still call for the continued support of the regime. Mr Teng recalled that “old diplomats” complained fiercely when China condemned North Korea’s nuclear tests in 2006 and 2009. And Tang Ge, a commentator whose blogpost is translated on sinonk.com, a website, thunders against those who argue that North Korea no longer matters to China as a “strategic buffer” between it and the American troops in South Korea. On the contrary, he claims, supporting North Korea is a “small-cost big-benefit” activity.

This suggests another way of responding to China’s poor relationships with its other neighbours: to recall that North Korea is an old ally—and as “close as lips and teeth” with China. It is likely to remain so, even if, for now, the lips are pouting and the teeth are grinding.

· Recommended

North KoreaRumblings from belowA sealed and monstrously unjust society is changing in ways its despotic ruler may not be able to controlFeb 9th 2013 | SEOUL |From the print edition

WITH her turquoise top, Dayglo trainers and Hello Kitty mobile phone, Jeon Geum Ju fits right in among the young latte-sippers in a Starbucks in downtown Seoul. Her dark eyes sparkle as she talks—and she talks a lot. The only time that the 26-year-old hesitates, and tugs at her hair awkwardly, is when she is asked about Kim Jong Un, the young leader of North Korea who took over her country in 2011,a year after she fled to South Korea. She was, she says, so brainwashed from a very early age that she still cannot bring herself to criticise him.

Ms Jeon is no apologist for the regime. Though her escape from North Korea was not caused by the starvation and abject cruelty that force others to leave, it was, she says, still a flight from oppression. What she craved was the freedom to wear flared jeans and jewellery and to let her hair, which most North Korean women keep in a bun, grow long and wavy. She even fantasised about driving a red sports car, with dark glasses on.

Related topics · China · Seoul She nurtured such dreams in her bedroom, watching illegal South Korean and American TV dramas smuggled in from China and shared among her friends on memory sticks which they plugged into black-market computers, some made by South Korea’s Samsung. She even flaunted her tastes in public. That was until the fashion police—no figure of speech in North Korea—arrested her for wearing a winter hat with “New York” on it. She was screamed at as “bourgeois trash” and released only when her mother, then a black-market trader, handed over two dozen packets of cigarettes as a bribe.

Such materialist tastes, however incongruous in a country where more than a quarter of young children are chronically malnourished, appear to reflect a changing reality in North Korea. While the Kim family dynasty, now in its third generation, seems almost immutable, the country that it rules over has altered dramatically. Instead of relying on state patronage for survival, people now hustle to make ends meet, and many of those who succeed use corruption, black markets, influence-peddling, inside information, criminality: in short, all the dark arts of an unregulated, out-of-control private economy.

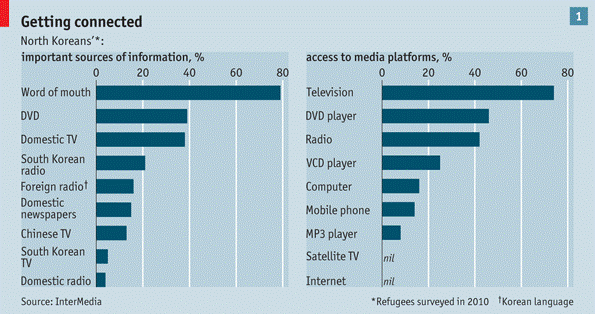

Until recently, the outside world has known little about North Korean society. But during the past decade information has flowed—albeit illegally—both into and out of North Korea (see chart 1). Last year an American government-backed report by InterMedia, a consultancy, welcomed the deluge pouring into the North through digital media and old-style broadcasting such as Voice of America and the Korean Broadcasting System. “North Koreans can get more outside information…than ever before,” it said, “and they are less fearful of sharing that information.”

This has had two effects. First, people inside North Korea with access to outside influences can now compare their impoverished lives with others’ elsewhere. That has helped trigger a craving for the material trappings of the modern world, and the flow of such contraband goods from China to the North Korean border, orchestrated or waved on by corrupt officials. It has, says Andrei Lankov, a Russian expert on North Korea at Kookmin University in Seoul, become a society where money now talks even more loudly than your relationship to the regime. “It’s a completely different society than it was 15 years ago. This has not happened because of government policy. It’s a change from below.”

Second, new information flows have given outsiders an insight into the changes taking place in North Korean society. This year, for the first time, Google and some dedicated North Korea-watchers have mapped the interior of the country, locating everything from underground railway stations to labour camps. That information will not be available to North Koreans, almost all of whom are barred from using the internet. But for outsiders it helps unravel the all-enwrapping shroud of secrecy.

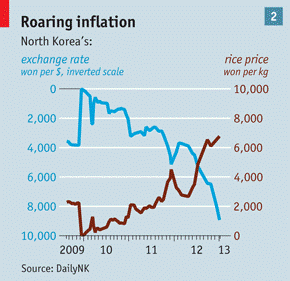

Meanwhile economists have studied defectors, making remarkable discoveries about the huge role private income now plays in people’s lives, and the changing sexual dynamics as women who run the black markets become the main breadwinners. Defector-led news sources, such as the Seoul-based DailyNK, amplify the information flow. They have built up contacts with clandestine sources inside North Korea, who use illegal mobile phones to provide news ranging from gossip about Mr Kim’s new wife to evidence of galloping inflation and currency turmoil (see chart 2). What has emerged is a picture of a two-speed society. Pyongyang has surged ahead of the rest of the country, the kleptocrats have grown stronger, and canny traders have joined a fledgling class of nouveaux riches.

These changes have been easy to miss with so much attention falling on the Kim family, particularly in the past year. The ascendancy of Kim Jong Un after his father’s death in December 2011 brought hopes that he might be a great reformer. His more boisterous style of leadership, supplemented by a fashionable wife and a taste for visits to fairgrounds, suggested that he might be closer to the people. His speeches were peppered with references to people’s livelihoods, rather than the “military-first” obsession of his father. Domestically, the greatest coup of his first year in office was the launch of a satellite into orbit in December, despite protests from around the world that he was experimenting with missile technology.

Partying in Pyongyang The change of mood is said to be palpable in the capital. “Pyongyang is more relaxed. It is still extremely repressive socially, but people are taking their cue from the new leadership,” says a diplomat who lives there. On New Year’s Day senior diplomats were invited to a party hosted by Mr Kim that included the scientists behind the rocket launch. Many ambassadors were delighted to shake the hand of the despot-in-chief for the first time—though there was chagrin that the former Swiss-school pupil did not speak English. “Not even ‘Happy new year’,” one guest noted.

Latest meeting of the Pyongyang Missile-Appreciation Society

The mood has soured since. Mr Kim’s new-year speech called for an end to confrontation between North and South. Yet as soon as the UN Security Council issued new sanctions against the regime as a result of the rocket launch, the response was apoplectic, warning of more tests and threatening to attack America. The son’s regime, it turns out, is no less capricious than his father’s was.

The changes beneath him, however, seem likely to continue. They are easiest to spot in Pyongyang, where the proliferation of new city lights is exclusively fed by the Huichon hydroelectric power station. The lights conspicuously stay on at night in some of the new high-rise apartment buildings; the plushest ones at Mansudae, 45 storeys high, flash in several colours. (Inside, though, residents are said to keep buckets of water in reserve for when the taps run dry.)

More cars run on better-paved roads. Rüdiger Frank, a German economist and regular visitor to North Korea, wrote recently that two-storey establishments with a shop on the ground floor and restaurant and sauna above have mushroomed. “Prices are horrendous; three kilograms [6.6lb] of apples cost as much as one (official) month’s wages. But the fact that even things like bananas are being sold is remarkable. The problem does not seem to be access any more…[just] having the right amount of the right currency.” One of those currencies is good information. There are said to be 2m PCs, 1.5m mobile phones, not counting the illegal Chinese ones, and a home-produced tablet computer. Behind closed doors, these have fostered new signs of change, such as the adoption among the elite of South Korean clothes, mannerisms and even accents. In his recent book, “Only Beautiful, Please”, John Everard, Britain’s ambassador to Pyongyang from 2006 to 2008, recounts a story of one mother, answering a phone call from one of her child’s friends, joking: “It’s Seoul on the line for you.” Yet there is also a dash of Potemkin about Pyongyang. Behind the high-rises lie unpaved roads. Stephan Haggard and Marcus Noland, of the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics, have referred to the “Pyongyang illusion”. They believe the authorities may not just want to improve the capital, but also to forestall an uprising among urbanites. And resources may be sucked from the rest of the country to pay for it. A widening gap also yawns between Pyongyang and the rest of the country. UN agencies reported a slight improvement in overall nutrition levels last year, but revealed a stark contrast between the level of stunting, or chronic malnutrition, among under-fives. The shares range from below 20% in the capital to almost 40% in Ryanggang province, part of North Korea’s most impoverished rural north. Genies into bottles Mr Frank, the German economist, notes that there is nothing unusual about growing gaps between the capital city and elsewhere. The regime may have decided, he says, to develop one city as best as they can, “rather than spreading their scarce resources across the country with a watering can and achieving no visible results.” Yet it is also possible that the brighter lights, firework displays and spruced up parks in Pyongyang are a cynical attempt to give unhappy citizens in the provinces somewhere else to yearn to live besides Seoul. It seems to be no coincidence that as the skyline of Pyongyang becomes more alluring, a severe crackdown is in force on TV dramas from South Korea and on escapes to South Korea via China: the numbers fleeing dropped by 44% last year, to 1,509. It is as if the regime is trying to stuff the genie back into the bottle—but too late. “The country is beset with macroeconomic instability, deepening inequality, rising corruption and a political leadership that appears to lack the vision or capacity to respond,” Mr Noland wrote last year. He talks of a “supply line” that now runs up the west of the country to Chinese towns like Dandong near the north-western border, along which raw materials flow in exchange for illicitly procured consumer goods that flow back the other way, paid for in hard currency. He says there is anecdotal evidence that senior officials are involved in these trades. For instance, a senior food-distribution official may have the best information on the rising price of grain, which means he will try to increase imports. His wife may well be the main grain-wholesaler in the black market. When there have been crackdowns on the markets, as during a disastrous currency experiment in 2009, Mr Noland reckons large chunks of the economy may have seized up because of shortages of basics, such as cement. This may have taught the authorities to turn a blind eye to the illegal activities. Even remittances from defectors in South Korea seem to be tolerated, provided officials get a cut. A system loosely akin to Islamic hawala has developed, in which money flows between banks in South Korea and China and brokers deliver the cash equivalent to family members in North Korea. Sokeel Park of Liberty in North Korea, a group which works with defectors, says this is how some people acquire cash to escape.

Enterprise, North Korean-style It is not just the elite who have benefited from what Messrs Haggard and Noland call “entrepreneurial coping behaviour”. Lee Seongmin, a 27-year-old defector in Seoul, had no such privileges when, at the age of 12, he started to sneak into China to find food as famine ravaged North Korea. At 17, however, he was caught, imprisoned and severely beaten. When he came out he decided to take a more enterprising route, befriending border guards and acquiring an illegal mobile phone from his sister in China. He started importing car parts, using his phone to call China for deliveries. The soldiers at the border would pull the merchandise across the Yalu river with ropes, he says, and he would pay them off. He would then use his job working for a state distribution company to truck the parts around the country. He made so much money that he had to bury it under his kitchen floor, and often regrets his impulsive decision to defect.

These illegal markets, Mr Lee says, have produced a class of new rich who sometimes flaunt their wealth—and pay off the authorities if they become too suspicious about it. Those with hard currency also instantly became relatively richer after the 2009 currency experiments, which had the effect of severely devaluing the North Korean won.

Since then, conspicuous consumption appears to have increased. Mr Lankov writes of rich people going to expensive sushi bars and buying illegal property, TVs and refrigerators. Their main complaint is the unreliable electricity supply. Perhaps the biggest luxury is a dedicated line to the local power substation, paid for by bribing a corrupt official or military commander.

These entrepreneurs may eventually pose a threat to the regime, though they also have a stake in preserving the status quo if it enables them to make money. The test may come if a serious attempt is made to seize their wealth. Alternatively, the increasingly visible gap between rich and poor may breed resentment. Ms Jeon says she was sickened to see one class of justice for the rich and another for the poor. One of her mother’s impoverished acquaintances was sentenced to death for helping two girls leave the country; the woman’s children were summoned to witness the firing squad without realising their mother was the victim. Ms Jeon surmises that if the woman had had more money or better contacts, she might have been spared.

North Korea has long been a grotesquely unjust society. But since a famine in the late 1990s killed up to 1m people, and led to the breakdown of the system through which food was distributed around the country, experts say the state’s control over people’s lives has waned. “North Korean society has become defined by one’s relationship to money, not by one’s relationship to the bureaucracy or one’s inherited caste status,” Mr Lankov writes.

As yet there are no visible signs of protest. There appear to be no covert human-rights groups, despite the estimated 200,000 political prisoners who fester in concentration camps, and no subversive intellectuals, as in the former Soviet Union. Ms Jeon says that it never once occurred to her to risk talking about regime change. Korean experts say the lack of resistance is not only the result of brainwashing. It is because North Korea’s tradition of oppression dates back to far before the Kims: for most of the first half of the 20th century its citizens were bossed around by the Japanese, and before that by a rigid monarchy. They know of little better.

There are, however, tentative signs of openness to the outside world. Groups like Choson Exchange, based in Singapore, and the Pyongyang Project, a Canadian-American NGO, have set up workshops with North Korean civil servants to discuss previously touchy subjects such as banking and finance. At times, the North Koreans’ambitions seem unrealistic: in 2010 one group was asked to lecture on how to establish exchange-traded funds and private equity, in a country without deposit-taking banks. But contact is as important as content, says one of the groups’ leaders.

Pressure is also growing for other forms of engagement—especially ways around North Korea’s information blockade. Some North Korea-watchers welcomed the visit by Eric Schmidt, executive chairman of Google, to the country in January as a step forward. The BBC World Service, too, is being urged to develop a Korean-language channel. In such endeavours, experts say, information on other ways of life is more valuable than political indoctrination. Mr Lee, the defector, believes that information should be as high a priority as food aid. “It is only when people can tell the difference between truth and lies that their curiosity is stimulated,” he says. Curiosity may be what this obsessively secret regime most has to fear. From the print edition: Briefing

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |