字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/05/12 01:22:43瀏覽54|回應0|推薦0 | |

Cambodias foreign relationsLosing the limelightJul 17th 2012, 5:50 by L.H. | PHNOM PENH

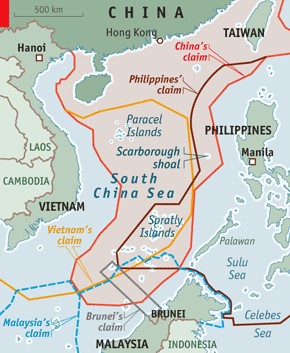

CAMBODIA rarely gets the chance to shine on the international stage. A decade ago it scored kudos for its first-time effort as chair to the ten-nation Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), a significant milestone for a country that was still struggling after 30 years of war. Phnom Penh’s diplomats revelled in the summits that came with the job and in the company of their guests, including America’s then-secretary of state, Colin Powell, and Japan’s prime minister at the time, Junichiro Koizumi. The dignitaries lent an unprecedented air of political celebrity to the capital. Since then, however, Cambodia’s external relations have changed. With billions of dollars of aid at stake, Cambodia has snuggled up to China and become its de-facto proxy within ASEAN. The attendance of Hillary Clinton, as America’s current secretary of state, could not make the same impression as Mr Powell’s. And China arrived with every reason to try taking advantage of its new leverage as Cambodia played host to the block for its second summit in Phnom Penh. At the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF)—where foreign ministers from South-East Asia and farther afield thrash out their differences—China picked a backroom tussle for influence in the South China Sea. Their Cambodian hosts might have been alone in failing to anticipate the manoeuvre. The remote Spratly islands are claimed in whole by China and in whole or in part by Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. The Paracels are claimed entirely by both China and Vietnam. China wants to negotiate disputes over the potentially resource-rich Spratly and Paracel islands with its neighbours on a series of bilateral talks. ASEAN would prefer to present a united front. America tends to see these matters in the ASEAN way. Two years ago China was angered by America’s declaration that it sees the South China Sea—which about half of the world’s ship-borne trade passes through—as a proper part of its own national interests. America ratcheted up the diplomatic stakes by signalling a realignment of its priorities back towards Asia. Central to this is the Code of Conduct (COC), a document that has been tossed around and discussed between ASEAN countries and China ever since Cambodia first time as the summit’s host. The COC’s purpose is to prevent or limit any military confrontation before it gets out of hand. Many argue the COC is needed now more than ever, with the frequency of clashes involving civilian and military vessels increasing over recent months. Cambodia attempted to nudge the COC along by writing up a list of “key elements” for which it hoped would win acceptance from ASEAN. Instead its proposal was criticised for lacking teeth and demurring to China—and for infuriating the Philippines and Vietnam, who have led the block on this issue. The negotiations quickly became heated. As reports circulated to the effect that Cambodia’s foreign minister, Hor Namhong, was simultaneously seeking China’s advice while negotiating with fellow members of ASEAN, the atmosphere grew dismal. The Philippines’ contingent then upset their hosts by insisting on a communiqué that mentioned their navy’s standoff with Chinese vessels at Scarborough shoal, a ring of mostly submerged rocks to the east of the Paracels. The Cambodians balked and in the end delegates failed to strike any deal on the COC. For the first time it its 45-year history ASEAN’s delegates also failed to issue a closing statement. Caught between defending the national interest and wanting to keep the Chinese sweet, Cambodia’s delegates went into ahuddle. Mrs Clinton took a moment to remind ASEAN that America had invested much more in South-East Asia over the years than China ever has. She also warned that confrontations over the Spratly and Paracel islands would probably escalate. “None of us can fail to be concerned by the increase in tensions, the uptick in confrontational rhetoric and disagreements over resource exploitation,” Mrs Clinton said. “We believe nations of the region should work collaboratively and diplomatically to resolve disputes without coercion, without intimidation, without threats and certainly without the use of force.” China does not want the issue settled by the international courts nor by the UN Convention of the Law of the Sea (to which it is signatory, though America is not). Its representatives said it would resume talks on a legally binding document, such as could regulate rade and shipping in the South China Sea, only when “the time is ripe”. Mrs Clinton left Phnom Penh for a side trip to Siem Reap, home of the 12th-century temple ruins of Angkor Wat, and then she was on to Myanmar. Left behind was Hor Namhong, who tried to explain the summit’s failure. “I have told my colleagues that the meeting of the ASEAN foreign ministers is not a court, a place to give a verdict about the dispute,” he mustered for reporters. The feuding over the South China Sea will be no less vitriolic for Cambodia’s efforts to mediate between China and its ASEAN neighbours. All that has changed is that Cambodia’s place within the alliance—and its relationship with China—are being questioned as never before. « Myanmars minorities: Caught in the middle · Recommended · 11 參考一篇網友的說法,很有趣: I will like to give a history lesson to our 10 year old Red Pioneers about ASEAN and South East Asia in general. South East Asia is divided along mainland South East Asia which comprises Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos. Archipelago South East Asia is made up of Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Brunei and the Philippines. Prior to the mid 1990s, with the exception of Thailand, all of ASEAN was made up of Archipelago SEA. In fact Lee Kuan Yew was not enthusiastic letting the Indochinese join, too many "issues and baggage"

Chinas economic influence in the older ASEAN countries is weak, China is usually the 3-4th largest trading partner in those countries, in terms of foreign investment its lucky to crack the top 10. In % terms, Chinese exports to Brazil make up more of the Brazilian economy than Chinese exports to the Philippines. Indonesia, Thailand or Malaysia. In Burma and Indochina, China is usually the 1-2st largest trading partner and usually the largest investor in those countries. The reason is historical, most of the good opportunities were long taken by US, European, Taiwan, South Korean and Japanese companies. Secondly, the older ASEAN countries are in fact competitors of China in many industrial sectors.

Lets not underestimate the duration or extent of US/ Western involvement in the older ASEAN countries. All of them were former European colonies, with the exception of Thailand. However, outside of the former US colony of the Philippines, there is no other country that has more extensive ties with the US than Thailand. In the 1960-70s, they had large naval and air bases in Thailand, where they conduct long range bombing raids into Indochina. When US serviceman went for R&R in Vietnam, they went to Thailand. The Thai Kings propaganda / projects campaigns were funded by the CIA. The US tentacles run very deep.

When you look at the elite of the these countries. Where do they educate their children, where were they educated themselves? Was it Beijing University, Fudan University. Here is an interesting breakdown.

Hun Sen - Commie, University too Bourgeois. SBY (Indonesia) - Webster College, US Army Command and General Staff College, (Ranger School, Airborne School, Infantry Officer Advanced Course — all at Fort Benning. The place of the infamous School of the Americas )

Aquino - Ateneo de Manila University

Out of the six older ASEAN countries, three are lead by people who have studied/trained with the US military. If Chinas influence was so great, why didnt they go train with your beloved PLA.

What is more scary, is their children. Hun Sens son graduated from West Point. SBYs son is at Harvard. Yingluck Shinawartas son studies at Harrow International School. Li Hongyi is at MIT.

Most of our posters white about American propaganda (media), but rarely talk about American brainwashing and indoctrination, which is more insidious. Most of the media in many ASEAN countries are controlled by Western educated elites, even the ones that write in the local language. They take stuff from AFP, Reuters, Economist and translate it.

Now why do they fear China? One factor is their ethnic Chinese minorities, but China has a nasty record of inciting revolt/arming insurgencies, getting involved in their internal affairs etc. The only difference is China never apologized to any of the countries like Philippines. Why did China send arms to the NPA in the early 1970s?

The fear of China (and India) is enough to drive suspicious neighbors like Australia and Indonesia to work more closely. Just last week, Indonesia sent their front line Sukhoi-30 MK2 to Australia.

http://www.theage.com.au/world/indonesian-jets-in-australian-war-games-2...

Why would the Indonesians all of sudden want to work closely with the racist Australians? Is it because they fear India? The US?

Losing the limelight Jul 19th 2012, 16:09

In geopolitical aspect, I recall that the dispute of South China Sea had been just a problem remaining murmur or sparkle until 2011’s the Economist’s annual issued the full-page report which let me contact Beijing for the serious problem. Before then, during the past two decades, the anonymous pirates emerged with intermittent battle. Some of them, comprised of religious radical, usually had Indonesia, Singapore and Philippines get headache. Compared with the rising economy of India, Taiwan and South Korea, this relatively poor region - surrounding South China Sea - lack of international order with weak security guard.

From the declined era owing to western power’s invasion - in the late Qing dynasty, the once-prevailing Republic of China and the present Beijing’s Communist Party - China’s central government has been controlling the whole sea escorted by the Qing dynasty’s Southern Oceanic Fleet and the aftermath of China’s navy. The fleet of Qing dynasty once won battle against that of Netherlands near Spratly Islands in 1905, uneasily ensuring the constant right of oceanic power’s position in Asia. Nowadays, Taipei authority’s military still holds Taiping island, the biggest in Spratly Islands, and Beijing’s People’s Liberation Army navy (PLAN) keeps the whole right of this sea in truth while other nation, surrounding this sea, constantly complain with no reason.

As one of three geopolitics issue along East Asia’s first-chain islands near Pacific Ocean, the dispute of South China Sea is hard to wane while, in this year, United States is in the process of adjusting the defense strategics in Asia-Pacific region. Scanning the recent history after world war II, in addition to Vietnam War, the military conflict near China and Vietnam’s border occurred in 1979. By the way, Wang Xi-hsin was one of those who joined in that battle and started getting promotion to the present utmost leader of PLA.

Although both China and Vietnam are one-party nation with socialist style, Vietnam gradually makes friends with western nation and neighbors, even becoming one of Japan and US’ crucial military allies for two years, but China - entangled by Sino-Japanese Diaoyu’s dispute and Northerneast Asia’s six-party zero-sum game - faced the difficulties of American shading play only to let herself admit that the dispute of South China Sea belongs to a region’s problem in Asia-Pacific. A good discussion of whether China turns to a politics and economic “isolated island”, having significant difference from neighborhood, also arouses with China’s foreign minister Yang Jie-chi’s exclamation in Phnom Penh.

Thanks to the good relation with Cambodia, China - at least having some room in this issue - can play card with the rest of ASEAN+3 under the “host advantage” atmosphere which contains the wrong claim of this sea’s territory for China. On one side, Cambodia wants to expand her international sound by chairing ASEAN with abiding by China-inclined policy. For several times, Philippine foreign minister wanted to state their concern about recent confrontations in this sea, but Cambodias chairman strongly opposed the idea. On the other, China discreetly takes advantages of Cambodia’s direction while both Vietnam and Philippines continues respective plan on this sea. After Philippine congressmen’s protest of landing on one of island and Vietnam’s active alliance with Japan, India and America with enraged Vietnamese ordinaries, last month, Chinas Civil Affairs Ministry announced an administrative districts integrating the Paracel, Spratly and Macclesfield Islands into the new city of Sansha. The citys headquarters will be located on Yongxing Island in the Paracel Islands, which are effectively controlled by China.

Given the advanced facility in Sansha, China becomes more active in the sea for the interest in sea of petrol-producing and for the right of navy’s advantage over the rest of Asian nation. Since the problem on this sea forms, moreover accompanying the intensively diplomatic pose by Japan and America in Vietnam, China can’t be allowed to just stand at the position of international law or historical heritage; furthermore, the eagle-like diction should be shown off and the military action should be not crossed out - of course the peaceful treatment keeps first. The present situation is not the peaceful a decade ago when Koizumi Junichiro and Colin Powell governed their contries. I believe that these two follow the historic evidence to say the sea belongs to China, as I have told Mr. Koizumi recently, who sometimes disliked the sayings of current foreign minister Koichiro Gemba. Pessimistically speaking, the multiple environment embarrasses China, the rising nation but often unwelcomed one. Never stops history anytime and anywhere as no excuse to leave anything alone.

Recommended 8 Report Permalink (未完成) *附一篇相關文章 Asian maritime diplomacyChinese checkersThe spectre of big-power rivalry spoils an ASEAN gatheringJul 21st 2012 | PHNOM PENH | from the print edition WHEN the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) sat down to a foreign ministers’ meeting in the Cambodian capital last week, it hoped to chalk up progress towards a European Union-style economic block by 2015. By the time the meeting ended on July 13th, it looked almost as dysfunctional as the euro zone itself. For the first time since ASEAN was founded 45 years ago, one of its meetings ended without a communiqué. No great loss there: such statements tend to be instantly forgettable. But the absence reflected a falling-out between Cambodia, chairing the proceedings, and members such as the Philippines and Vietnam. This, in turn, reflected what analysts say is a growing rift between ASEAN countries loyal to China, and those contesting territory with it in the South China Sea, a group that increasingly looks for support to America. The acrimony was almost unprecedented in a group which, according to the Straits Times, a Singaporean newspaper, likes to resolve disputes “quietly amid the rustle of batik silks”. The assertion, made between diplomatic clenched teeth, was that Cambodia bowed to China in blocking an attempt by the Philippines and Vietnam to refer in the communiqué to Manila’s recent naval stand-off with Beijing over the disputed Scarborough Shoal. In this section Indonesia, bravely trying to find a way to mollify the chair, reportedly offered 18 different drafts for approval; all to no avail. Its foreign minister, Marty Natalegawa, expressed “profound disappointment” over the outcome. Behind closed doors, the atmosphere was poisonous. Even in public, the bitterness was surprising. Cambodia pinned the blame squarely on those who it said wanted to “condemn China”. The communiqué was not the only casualty. Following the Philippines’ dispute with China, and the lingering tussle between China and Vietnam over ownership of the Spratly and Paracel Islands and oil-drilling rights nearby, ASEAN had hoped to conclude a code of conduct, ten years in the making, to help keep the peace in a stretch of water through which half the world’s shipping travels. The code, which is strongly supported by America, was expected to cover issues such as the terms of engagement to be used when naval vessels meet in disputed waters. Its progress was unclear. China, which has long insisted that maritime disputes should be settled bilaterally with its smaller neighbours, rather than multilaterally, through forums such as ASEAN, only agreed to discuss the matter “when conditions are ripe”—an open-ended formula that further muddied the waters. Both China and America put positive spins on the outcome. The Chinese described it as a “productive meeting” in which its views had “won the appreciation and support of many participating countries”. Hillary Clinton, America’s secretary of state, sought to hide her disappointment. She said it was a sign of a growing maturity that ASEAN was “wrestling with some very hard issues here”. Within the organisation, however, the fear is that its cherished autonomy and ability to compromise—the so-called ASEAN way—is under threat from big-power rivalries, however reluctant China and America may be to risk naval escalation. The Cambodian government insists there are no strings attached to more than $10 billion in foreign aid and soft loans that it has received from China during the past 18 years, but there is no doubt that Beijing has an influence: some of the maps in the Peace Palace in Phnom Penh had Chinese place names in the South China Sea. Analysts say that Laos, also bankrolled by China, is in its camp. Maritime states such as the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia are more concerned by China’s muscle-flexing. However, some commentators fear that too much American support may be emboldening countries like the Philippines to be more assertive within ASEAN about their problems with China. Japan, too, supports the idea of a pro-American grouping in the region to counterbalance China. North-east of the South China Sea lies a small crop of islands that Japan and China are squabbling over. All such disputes stir up intense nationalist feelings around the region, which makes it difficult for diplomats to settle matters placidly. All the more reason for a maritime code of conduct to make sure hot-heads do not call the shots. from the print edition | Asia · Recommended

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |