字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/10/10 01:29:22瀏覽49|回應0|推薦0 | |

本文是當期經濟學者雜誌文章中國欄首篇,10月4日首發,直接證實筆者在今年四月所聽到的中國大陸內政上動亂的疑慮,雖然沒有大規模的集結,但是標榜維權的,不管是社會改革浪潮或是社會動亂,官方已經很難完全平息,省級官員在回答中央的意見書中,提及根本是職業化成功,間接證實習近平的社會控制並沒有因為作強化馬克斯主義的政治控制而變強,反而變弱。筆者還不幸地猜對,但可惜沒有辦法拿獎學金,對筆者這種支持黨中央的人,矛盾地說也不是很光彩的事,就是社會的矛盾加劇容易導致黨政系統的崩潰。經濟學者雜誌拿出Wechat微信浙江省的證據,把浙江省的例子提出很恰當,發現無理掠奪土地的官員增加甚多,但在習近平作肅貪措施後,土地價格飆漲的情形不再,這個理性面是很不錯的說明。接著由於房價還是沒有下跌,還是沒有房子住,而生活水平無法一下子「跟上」房價的價位,所以最近又有一波新的抗爭。 Masses of incidents Why protests are so common in China They are rarely about politics, but they are evidence of social stress

Print edition | China Oct 4th 2018 | BEIJING THE last tweet sent by Lu Yuyu before his arrest two years ago was typically terse. “Monday June 13th 2016, 94 incidents” it read. Appended was a link to a page on his Blogspot website (newsworthknowingcn) listing details of those cases. They included a protest by more than 100 parents complaining about a local-government decision to make their children attend a distant school instead of a nearby one; another by dozens of farmers enraged by the seizure of their land by village officials; and a demonstration in Beijing by around 2,100 ex-servicemen demanding better benefits. For his painstaking efforts to catalogue unrest in China—Mr Lu and his girlfriend had recorded more than 70,000 outbreaks in the three years before he was seized—the activist was found guilty last year by a court in Yunnan province of “picking quarrels and causing trouble”. He was given a four-year jail sentence. There was a time when the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) itself released annual data relating to “mass incidents” around the country, even if it kept quiet about the details. In 2006 it said that 87,000 of them had occurred in the previous year, nearly 7% more than in 2004 and up 50% since 2003. But over the past 12 years the government has ceased providing such figures (a report in a state-controlled journal said the number had doubled between 2006 and the end of that decade, which many analysts took to mean that about 180,000 incidents occurred in 2010). China-watchers who had used the numbers to assess the country’s stability have been left with little to go on but anecdotal evidence and statistics produced by researchers such as Mr Lu, which are mainly gathered by trawling through Chinese social media. The MPS figures were highly suspect. The definition of a mass incident was fuzzy. The figure for 2006 was said to relate to “public-order disturbances”, an even woollier term which could apply to activities such as unauthorised religious gatherings or illegal gambling sessions as well as to demonstrations. The figures were probably far from complete. Local officials had little incentive to report every case to their superiors. The MPS had every reason not to paint a picture of turmoil publicly. But the trends suggested by the MPS figures were still often cited by analysts as evidence of a country that was suffering mounting social stress. There was little sign that political protests involving explicit criticism of the Communist Party or its leaders were becoming more common. Yet the numbers were proof enough that citizens were increasingly prepared to take their grievances to the streets, despite the party’s abhorrence of public protest. Since the most recent figures were published, it might be supposed that this trend continued for a while before coming to a halt and possibly going into reverse. Controls on the internet have tightened. Police have become more adept at anticipating unrest by monitoring online chatter. Activists using the internet to organise demonstrations (or, as in the case of Mr Lu, to publicise other people’s protests) have been given lengthy jail terms. Since he took over as China’s leader in 2012, Xi Jinping has been waging a relentless campaign against civil society. This has involved sweeping arrests of NGO workers, independent lawyers and rights activists. Surprisingly, however, Chinese academics and foreign researchers have found little evidence that the trend has changed. In an article published in May, Yu Yanhong of the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE) in Beijing wrote that mass incidents had grown from being relatively small in number and scale into a “prolonged high-level state” (pictured is a protest in Beijing in 2016 by parents whose only children had died when the one-child policy was in effect). Trouble spreads China Labour Bulletin (CLB), an NGO in Hong Kong, monitors protests involving workers and uploads the data into a frequently updated “strike map” of the country on the group’s website. Geoff Crothall, the group’s spokesman, says collective action by workers has maintained a “continuous high level” in recent years. The unrest is no longer so concentrated in factories in the Yangzi and Pearl river deltas. Across the country, service industries such as taxi and food-delivery companies are increasingly affected. The group has obtained details of 1,257 protests in 2017 and of 1,318 so far this year. Mr Crothall reckons that incidents coming to the attention of his group are probably only about one-tenth of those that occur. State media keep quiet about most of them, such as strikes by thousands of lorry drivers in several provinces in June over pay and rising fuel costs. Christian Göbel of the University of Vienna has analysed the cases that were logged by Mr Lu, the jailed activist. Mr Göbel writes that most of them involved demands relating to pay and compensation. They occurred mainly around the Chinese new year, when workers traditionally expect the settling of unpaid wages. But the protests involved a wide social spectrum. Demonstrations by homeowners against property-management and property-development companies “increased steeply” during the three years covered, he says.

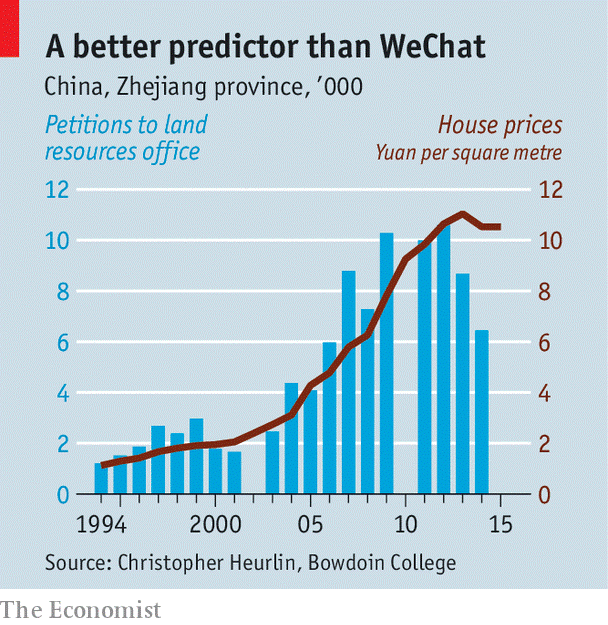

Mr Göbel notes that protests against land-grabs by officials in the countryside did not feature prominently among those recorded by Mr Lu. But affected farmers often use the petition system, which allows citizens to seek redress for official misconduct by lodging a complaint at designated offices. Based on data from the eastern province of Zhejiang, Christopher Heurlin of Bowdoin College in Maine reckons that the numbers of petitions filed is linked with rising land values (see chart). The higher the price of land, he says, the more likely officials are to seize it and displaced residents to protest. Although petitioning is legal, police often round up those who submit complaints, fearing that they may try to gain attention by airing their grievances on the streets. In June hundreds of army veterans staged protests in the eastern city of Zhenjiang after an ex-soldier petitioning at a government office was beaten by security guards. Social media play a powerful role in helping protesters to organise. For all the expertise gained by the police in monitoring online activity, and by censors in deleting sensitive content, internet users have become increasingly skilled at evading attempts to block sensitive messages. Those who blatantly call for protests are likely to be pounced on quickly. Earlier this year, a crane operator in Hunan province posted a message on WeChat about a planned strike on May 1st. Within a day he had been picked up by security agents, who ordered him not to take part. But Mr Crothall of CLB says that workers are using social media to share their complaints and co-ordinate their demands, assign specific roles to different activists and alert journalists. In March 2017 more than 800 online chat groups were formed by residents of Sihui city in Guangdong province in opposition to the building of a waste incinerator, says a report by academics at Jinan University in the provincial capital, Guangzhou. (They did not name the city, but its identity is clear.) The researchers said protests against the project, involving more than 10,000 people, bubbled up from WeChat forums. Given the intensity of Mr Xi’s clampdown, it is remarkable how willing some activists remain to wage public campaigns that annoy the government. This summer, students from prestigious universities travelled to Shenzhen to support factory workers there who were trying to form a union. Some of them were arrested. Students have also been at the forefront of China’s #MeToo movement, attracting much online attention with accounts of alleged sexual harassment by academics and public figures. Since the Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 the party has been especially nervous of student-led protests. Few have occurred, except in support of nationalist causes. But recent campus activism suggests that rebellious embers glow. Analysts debate how much the number of protests affects the party’s grip on power. A recent report by CLB calls the “intensification of social contradictions” in China a “direct threat to the legitimacy of the regime”. But Mr Yu of UIBE argues that the “astonishing number” of protests has had “no major impact on China’s political stability”. He writes that it would be difficult in China for those with grievances to form a political movement. Some Chinese scholars argue that protests can usefully allow people to let off steam. What is clear is that the public’s fear of the government is not as great as might be expected, given Mr Xi’s strong hand. That is fine for the party as long as most people support Mr Xi or are prepared to put up with him. It becomes a problem if the public mood changes. This article appeared in the China section of the print edition under the headline "Masses of incidents" |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |