字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/22 01:06:00瀏覽46|回應0|推薦0 | |

The Economist in ChinaOld handsFeb 27th 2012, 5:48 by G.E. | HONG KONG

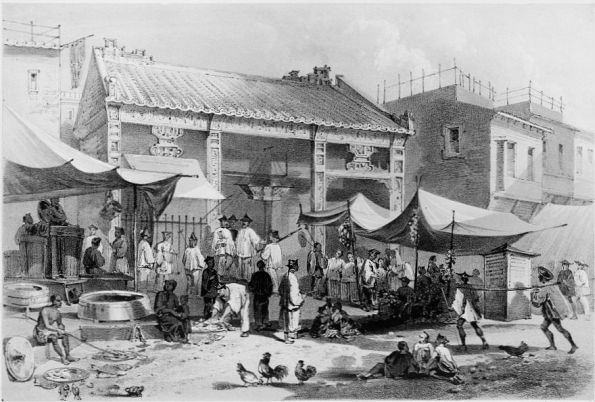

IN OUR nearly 170-year history, The Economist’s coverage of China’s Boxer Uprising of 1900 was not a high point. On July 21st 1900, under the headline, “The Situation in China”, we reported without a shred of doubt that the Chinese government had “succeeded in murdering all the Ambassadors of all the Powers who sent representatives to Pekin, with their wives, secretaries, interpreters, and guards.” We adjudged that “China has deliberately inflicted upon all Europe and Japan an insult without a precedent in history,” and that Europe “must avenge it in some adequate way.” If you missed this unprecedented mass murder of diplomats in your history books, that is because it did not happen (though the embassy district was indeed under siege by the Boxers for 55 days); it was a fiction propagated by Western newspapers, led by London’s Daily Mailand then theTimes,with The Economistjoining in days later but no less ardently (the newspapers later backtracked, without apology). The vicious and disproportionateresponse of the troops of the Allied powers to the Boxer threat, just 11 years before the downfall of the Qing dynasty, is now fixed in the Chinese lore of Western oppression. So it is with humility that we suggest that the quality of our reporting on China has improved somewhat since then. One crucial improvement is that we have our own feet on the ground in China, now numbering more than ever—three pairs of them in Beijing and more in Hong Kong. Four weeks ago, we began devoting a section to China in the print edition each week, the first time we have added an individual country report since we added America 70 years ago. Now we have introduced this blog on China as a companion to the expanded print coverage. But even with fewer or no feet on the ground, The Economisthas been opining on this place since the newspaper’s first months of publication in 1843, when updates from “Canton” arrived in the post, by way of a slow boat. The first extended analysis of China came in the eighth issue, dated October 14th 1843. The subject may ring a bit familiar: the potential of China’s consumer market to buy foreign imports. The Economist’s founding editor, the Scottish businessman James Wilson (who in those days wrote virtually the entire newspaper) was not bullish: “The truth is, it requires something more than treaties between governments to make trade.” Mr Wilson observed trenchantly that Chinese consumers have their own peculiar needs that are not met by foreign products, and that their incomes will need to rise as well. “We must not forget” of the Chinese, he wrote (without a byline, same as today), “… the mere liberty or opportunity of buying our goods, does not confer on them at once the ability to do so.” By 2012, it can now be noted, the consumer market for foreign luxury goods developed rather nicely. In December 1843, The Economistrelayed its first reported anecdotes about China: tales of foreigners being deceived by fake Chinese products. These included, according to one written account, “counterfeit hams” made of wood, coated in dirt and wrapped with an outer layer of hog’s skin: “The whole is so curiously painted and prepared, that a knife is necessary to detect the fraud.” Another foreigner, “M. Osbeck”, told of being duped by a blind flower-salesman on the street: “I learned from this instance that whosoever will deal with the Chinese must make use of his utmost circumspection; and even then must run the risk of being cheated.” The same 1843 article, headlined “Russian Trade Overland With China”, observed that Russia had “a great moral superiority” over the British in trade with China because they were not “engaged in the degrading trade in opium”. For The Economist, this marked the beginning of an estimable record in opposition to Britain’s and the other European powers’ exploitive, militarily backed trade policy with China. In 1845, The Economisturged the reduction of a steep tariff on Chinese tea, in line with the central founding principle of the newspaper: free trade. In 1859, The Economist, very much against the tide of national sentiment, castigated Britain’s arrogant treatment of China and argued in vain against waging what would become known as the Second Opium War: “There is nothing like the arrogance with which Englishmen are disposed to treat the great Oriental nations,” the newspaper wrote in one edition, going on to “record our emphatic protest against a false and arrogant tone of dictatorial ignorance which is growing up in England with regard to Oriental States…” This moral outrage against intervention in China did not come without patronising arrogance of The Economist’s own, including this, also from 1859: “No nation in the world is so slow as the Chinese in taking in new ideas; and their prejudices are so deep-rooted that nothing but time can alter them.” Not only did the newspaper argue against military intervention in China, it also at almost the same time threw in its lot with the authoritarian Qing regime in Beijing against the Taiping rebels who nearly toppled the dynasty in more than a decade of carnage. The Economistdemonstrated a bias in favour of regime stability in 1862 that would be comforting to the leaders running China today: “The Government of the Emperor,—which we fear that England has done too much to shake and injure,—bad as it is, is not a destructive Government. All its vices have been the vices of a corrupt and greedy bureaucracy, not of a desolating anarchy.” Meanwhile, “the Tae-pings are a mere horde of depredators.” (A new book by Stephen R. Platt, “Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom”, offers a dramatically different assessment of both sides in that bloody civil war, which the Manchu Qing ultimately won with the help of the British and American governments). Such 19th century insights were hindered greatly by the fact that The Economistrelied heavily on the Foreign Office and on other press reports for its information. After the Qing dynasty fell in 1911, this began to change. Accounts from a “special correspondent” in Beijing in 1913 accurately conveyed the sorry and tenuous state of the young Republican government of that period. In June 1949, when Mao Zedong and his band of revolutionaries were on the verge of establishing the People’s Republic, the newspaper’s “special correspondent” in Hong Kong relayed the discipline that prevailed among Communist soldiers, the transformation of its media into “organs of propaganda”, and the nervous mood of some among the public, in a long article titled, “China under the Communists”: There has been no terror yet in Peking or Tientsin, and it is probably too early to say whether Communist China will develop into another police state…Nevertheless, the Chinese wealthier and middle-classes and all those who had any contact with the nationalist regime are in a state of considerable anxiety about the future. The reporter also wisely dismissed the persistently sanguine view of some British merchants in Hong Kong, who held that not much would change under the Communists. Astutely, the correspondent believed it more likely “that what is happening is something completely without precedent in Chinese history of the past one hundred, or one thousand, years.” A year later, in 1950, The Economistgave an eyewitness account of the new China with a colourful dispatch titled “Marxist Shanghai”. Authored “by a correspondent recently in China”, it talked of a city fascinated with its communist condition, with bookshops full of literature on Marxist theory, communists putting on plays and the sounds of the song “The East is Red” playing in the streets: But no impression could be more deep or more lasting than that of the immense evangelical force of the movement. As one sees it in Shanghai it is a pill presented with a little coating of jam. The attack is insistent, for new hearts go hand-in-hand with new thoughts and in this process of regeneration ‘self-criticism’ plays so large a part and seems to be having so considerable an effect that it deserves at least closer attention than the slightly sneering tone in which it is often dismissed in the Western press… Over the next quarter-century, until Mao’s death in 1976, the newspaper’s reporting (like that of others) was hampered by an inability to travel the country at will. As such, Mao’s purges were reported, but without enough detail of their brutality, and the calamitous famine of the Great Leap Forward was not grasped in real time. The crazed excesses of the Cultural Revolution were reported with much more clarity and detail, thanks to the distinguished work of Emily MacFarquhar, whose expertise on China stood out both at the newspaper and among her peers in journalism; still more of the insanity and chaos would come to light only much later. This was how Mao wanted it, of course. Though The Economistwas by no means blind to Mao’s totalitarian rule, the newspaper was not able to observe firsthand its worst effects. As a consequence, The Economistrendered too kind a verdict upon Mao’s death in 1976.Among other accomplishments, he was credited with having built an “egalitarian state where nobody starves”; true, perhaps, that nobody was starving to death at the moment of writing, but the horrible fact that 20m to 30m of Mao’s subjects had perished in famine would emerge only years later. Since Mao’s death and China’s opening, The Economisthas been able to report more knowledgeably from inside the country. The newspaper first took full advantage of this in December 1977, with 24 pages of reportage and insight on China from Ms MacFarquhar and two other senior staffers, with the cover title “Chairman Hua’s China”. Given that Hua Guofeng, who was Mao Zedong’s hand-picked successor, would not last another year in power, some predictions understandably hit well wide of the mark, and there were some grave underestimations of the damage done to China during Mao’s rule. This included the judgment that “most Chinese are rightly grateful for what their government has done since 1949”. Such are the hazards of contemporaneous writing. We know today with the benefit of a longer lens that many Chinese are more grateful instead for what their government has done since those words were written. As it happens, Norman Macrae, the then-deputy editor of The Economist, predicted this would be the case. His prescient contribution to that 1977 report, beginning under the title, “A miracle has been postponed”, predicted that Chinese leaders would soon reinterpret Mao as they liked (while not abandoning him in name), liberalise the economy and launch decades of 10% annual economic growth. Fifteen years later, in 1992, Jim Rohwer explained in another special report how the reforming Chinese economy was even more vibrant than outsiders supposed, and was poised to keep booming for yet another 20 years. The newspaper was sometimes too close to the action to get the underlying story right: On May 20th 1989, The Economist(and other Western media) almost wrote Deng Xiaoping’s political obituary, swayed by rumours just hours before our publishing deadline that he was stepping down in the face of student protests; the newspaper noted the 84-year-old Deng’s shaky use of chopsticks on the occasion of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s visit that week. “And while Mr Deng grew older and feebler, the China around him changed, too,” we wrote. Weeks later, Deng was in as firm control of power as ever, and the newspaper would lament the bloody crackdown near Tiananmen Square that proved it so. The Economist established a permanent China bureau in Beijing in 1997 (the application was first made in 1994; the authorities were in no hurry to approve it). From that perch, the newspaper chronicled the historic transformation of the economy and China’s place in the world that has compelled so many news organisations, including ours, to expand our presence. The country’s transformation continues: in this week’s China section, we note that economic development of interior cities like Chengdu and Chongqing has progressed to the point that history’s largest in-country migration of workers is now reversing its flow. Both in print and here at Analects, we endeavour to convey a fuller picture of a China that has changed dramatically since we began paying attention in 1843—politically, socially, culturally and economically. Certainly, the story has developed beyond the narrow scope that the newspaper conceived in that first article about China, in October 1843: …that our demand for their produce will stimulate increased industry, produce among them more wealth and more ability to consume our goods, is certain; and a large and regularly increasing trade with this extraordinary people may be experienced for many years to come, and in the course of time…arrive at an amount at present little thought of. Little thought of indeed. Allowing for grievous errors like the account of the Boxer Uprising, we have done our best to provide worthwhile reporting and analysis on China in our pages for nearly 170 years. Long may useful fragments continue to find their way into print, and into these Analects. (Picture credit: "Canton Fish Market", Library of Congress) · Recommended · 21 · inShare9 Related items筆者在此附一篇雜誌中國版Analect的開版文 Our new blog’s nameHere be AnalectsFeb 24th 2012, 16:41 by J.M. | BEIJING

CHOOSING a name for our new China blog was difficult. Even before we decided to call on readers to offer suggestions, Economiststaff had argued over the possibilities. It quickly became clear that in the case of China, such nomenclature risked being snared by two big traps. One was an abundance of clichéd icons, from pandas and dragons to lanterns and the Great Wall. The second, more difficult to evade, was an interweaving of history with the politics of China today and the country’s troubled relationship with the West. Thus Confucius, whose name was suggested by several readers, appeared to us to be too closely linked to a simmering debate within the Communist Party. Are the ancient sage’s teachings to be praised as the quintessence of Chinese-ness, or rejected (as they were by Mao Zedong, who conveniently ignored his own despotic tendencies) as the ideological foundation of centuries of “feudal” rule? The brief appearance of a Confucius statue near Tiananmen Square a year ago, followed by its sudden disappearance only three months later, hinted at the acrimony of that argument. A sage of similar vintage, Sun Tzu, was suggested by several readers. But as we reported in December, his popularity with self-help and management gurus of the West distracts attention from his murky entanglements in China (Mao used him as an exemplar in his battle against Confucius). Several great leaders from China’s modern or ancient history suffered similar handicaps. The 18th-century emperors of what is regarded by some Chinese as a golden age may have led China to unprecedented wealth and power, but they were hardly champions of free trade. The territories they added to their empire are topics of fierce dispute today. Then there have been numerous reformers and modernisers since the 19th century, including Liang Qichao, Kang Youwei and even Lin Zexu. But naming a blog after one of them risked being drawn into one or another struggle that is still raging in China. Catchphrases referring to events in China’s modern history seemed similarly troublesome. Some of you proposed Hundred Flowers, a term that commonly refers to a brief period of political relaxation in 1956, which Mao cut short bloodily with a fierce campaign against the party’s critics. But Hundred Flowers is still used by the party today to refer to a supposed diversity of thought under one-party rule. There are Hundred Flowers awards for films, for example, for which the party’s critics need not bother trying to secure nominations. A couple of readers deftly avoided such politics by suggesting the blog be named “Interesting Times”. Sadly the Chinese curse to which this is supposed to refer is a Western invention. The Economist’s growing vegetation-fatigue (we have three blogs already named after trees: Banyan, Baobab and Buttonwood) dimmed the prospects of several candidates in this genre, from bamboo to ginkgo (or yinxing). Hutong might have been a good choice, but some might have complained that the word, referring to Beijing’s narrow alleyways, is borrowed from one used by the city’s Mongol conquerors of the 13th and 14th centuries. Drum Tower was another option, but one colleague felt it evoked “pre-programmed output for the purpose of marking time”. In the end it came back to Confucius, or at least to a word connected with him. The Analectsis the title of a collection of his sayings, but our fondness for the name does not imply endorsement of his philosophy. Its appeal is as a word in English.Its origin is the ancient Greek analekta, meaning “things gathered up”. James Legge, a Scottish missionary whose 1861 translation of The Analectswas the first in English, described the Chinese name of the work, Lunyu ( 論語, or 论语 in simplified characters), as meaning “digested conversations”. His use of the classical-sounding “analects” to render this idea reflected the learning that the West’s earliest China-scholars brought to the new field. “Analects” is now inextricably linked in English with the Confucian work, but the word itself means something very close to what our new blog is: gleanings, in this case from China. So congratulations to those who suggested the word. Several of you did, including insidious western media, guest-iinmjen and Ryan1512. But the first was JanisMagdalene. · Recommended · 49

Old hands Mar 1st 2012, 17:12

For nearly one plus a half century, the Economist always plays observative roles in the world’s news forum, also having been evidencing China’s decline and recover of prosperity in 20th century. Nowadays China already arrives at the crossroads of fate and fortune with so many focuses.

By the chance of the newly-open blog, I take another magazine for an example, Time Magazine, which originated somewhat from China. It is China that Time Magazine’s founder, Henry L. Ruce, was born in; therefore, this magazine always expresses different emotion from the rest of the world. On Sep. 8th, 1924, the cover story depict “King of Luo-Yang”, General Wu Pei-fu, as the biggest man in China, beginning numerous Chinese whose face become the mainstream in the world. For a long time, Time Magazine plays the most crucial part in criticizing China and steers the world the main direction. And many world’s media like Financial Times, Asia Times have their independent writers and columns talking about China earlier than The Economist.

In reality, there are too numerous to mention very and various kinds of Chinese figures, stories and freshness. Indeed, to construct an individual place in an international issue need the cause of special discussion. In Asia, China and Japan are the two which mainly play the most importantly forever and the ever. In almost of aspects except military concerned, Japan whose gross economy and politics grew to maturity in 1970s cannot be seen as a independent title of columns. There were so many famously outstanding figures, including scientists, politician and artists, better than Europe’s and America’s. Interestingly, it seems to exist only Renminbi’s ingredient which surprisingly let China be seen as the independent part in more and more issues. Then I pondered who the Economist’s reader is, finding out the majority of these who is busy in the leading business and researching centers. Besides, the recover of rise and the rate of acceleration in China are the unprecedented process of world economy.

Experiencing both noise and harmony from Kuomintang's (KMT) reign to the upcoming second peaceful transition of power in Beijing, China recovers the massive economy related to the rest of the world. China’s history has been evolving for so long five thousand years since Huang-di, the Chinese mutual ancestor. When it comes to the contemporary China, a vast amount of Chinese history, cultures and custom can be made an analogy metaphorically to describe the political and economics affairs.

Basically, Chinese don’t like foreigner talks of China’s affairs. However, the Economist, based on conservation and internationalism, has the ability to analyze China’s news predict China’s future while special events happens in other areas. Being a supporter of China’s Communist Party (CCP), I have read this Economist for nearly eight years in Taiwan. As the sayings of Wei Jen in Tang dynasty, “retrospecting the history like mirror reflects the present surface”, China isn’t the country which occupied only one island but say own the whole China while the seat of Chinese leaders will turn to the fifth generation of CCP who sometimes take the Economist to be the reference.

Also, as we see the desription and the following “Accounts from a “special correspondent” in Beijing in 1913 accurately conveyed the sorry and tenuous state of the young Republican government of that period” , the Economist may expect the real future of China and wants to give the direction of lighter China, rather than KMT’s regime or the similar style. Moreover, the process of democracy in CCP might be talked in this Analects.

I hope the Economist would be the guide of China’s developing economy and could report more and more how beneficial China becomes the strong power in the world, such as the either way of soft- and hard-landing, although I am somehow unpleasant owing to the new blog name. From Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary’s definition, Analects means “selected miscellaneous written passages” which is hard to be sign of China but is referred to as the “borrowing”, Confucius sayings. Truly, there are more than Analects flourishing in China, including the interaction of Chinese each other along with foreigners and the collection of stories and impression.

Recommended 23 Report 這篇經濟學人的原文是中國版Analact 開版的第一篇,筆者也在討論區回文提及,比起美國時代雜誌、英國金融時報及香港電子的亞洲時報或南華早報(在馬雲購買前的),經濟學人在報導中國新聞面,比較注意法規一致性、國與國邦交對等及國際政治道德問題。在從1843年出刊後,敘述太平天國的問題時,以帝制清廷觀之,雖很顢頇而貪汙及貪得無厭,但還不是毀壞的政府。因此如原文第一段所說,痛恨中國政府放任義和團拳亂濫殺駐華使節、傳教士、外國商人及本國教民實為無恥行為,同時要歐洲及日本作"適當的"報復。也就是說,讀這本雜誌有一種矛盾的問題要注意,但比較少,是民族尊嚴和情緒及法治理性面的妥協。這本比較溫和,或是會兩方面並列來說。畢竟是國際主義和保守經濟主義的刊物,相較於世界各國跨國媒體及美國媒體,對中國人來說也比較耐看和客觀,雖然在它出刊一開始時,英國政府佔了不少中國清廷的便宜說在「做朋友」。 第一篇和中國有關的是由蘇格蘭籍的雜誌創辦人James Wilson,寫了一篇對中國的舶來品消費潛力分析,並提出應要英國政府簽訂更多條約擴展自由貿易。1845年這本描述及分析比較帝俄「對中國的影響」和英國有什麼不同,是在「道德上」至少沒作鴉片或損害人權的生意,而同樣戕害中國國格,這裡就是指「The Great Game」英俄大博奕,主要是在中亞和西亞,在中國次之,這演變最後好在劃分勢力範圍,即甲午戰爭後清廷的最惠國範圍時帝俄沒有擴及長城以南,英國是長江以南,因此在中國方面沒有嚴重到直接的軍事衝突。當英國政府之後要求清廷廢茶葉出口稅時,經濟學人雜誌很明顯愛它自己的母國,很富本位主義的責罵清廷不接受新思想和蹣跚於近代化的進步,而不會理任何需要維持中國國家利益的問題。 在中華民國建立之後,1913年開始有在北京有特派員發稿說明,但這是個亂無章法的國度,在這篇原文算直接跳過到了1949年,說明對共產中國的描寫,如在上海的所見所聞,從香港發的稿,看到市民們「自我批判」,到華國鋒之前所報導及評論者礙於採訪不易而有限度提及毛澤東主導的大躍進和文化大革命的殘暴。1977年之後在一次以24頁寫成的預期經濟起飛後,在15年後回顧的自信於精準預測。在1989年的六四天安門事件時,這作者提及蘇聯主席戈巴契夫面見鄧小平時,曾經哀傷了一句要讀者長遠來看,鄧會老去而中國會變的。這當年的作者敏銳度很高,當時大力開放的蘇聯和這中國形成強烈對比,筆者從鮑彤的趙紫陽回憶錄「Prisoner of the State (國家的囚徒)」,於之後提及並引用時代雜誌「The Requiem of the reforrm (改革輓歌)」,曾經判斷在戈氏來華前一至兩天,鄧應該已經決定好過數天的政治軍事行動,甚至應在江澤民先生從四月底最後一次調解無望時就根本想出動軍隊作「直接處理」,由萬里曾經被拘禁十天以上的人身自由得之; 把當時人大常委長限制無異於凍結憲法的舉動,的確比帝制還令人心寒。 經濟學人這原文也順便提了「現在進行式」,即最新看成都和重慶附近的工人遷徙規模,似乎附近的產業升了級,也讓新一波的工人在這兩地附近有了作事和飯碗。不忘初心的雜誌,雖仍有些差強人意,仍很令人感動對於中國的分析及適切的態度。在六四天安門事件後,紙本的封面是共和衛隊的整隊畫面,主權和人權民主兩方面都有顧到,大方向和小遺憾遺落者也有所交代,這是其他西方和日本媒體當年沒有作到的事。 筆者回覆時,提及中國也可看成是各色各樣的人物、故事、文化、歷史及大脈絡交織而成的,有些偏提醒中華民族上有點存在主義的毛病,不過算偏謙沖自牧的特色也是一個很大的優點,反思就如唐太宗光祿大夫的一代名相諫臣魏徵所言:「以銅為鑒,可正衣冠;以古為鑒,可知興替;以人為鑒,可明得失。」也希望能記得報導中國的外國媒體有包括在這塊領域也頗富盛名的時代雜誌,1923年3月3日出刊後,第一個被刊出的是「洛陽王吳佩孚」在1924年9月8日,是當時中國軍閥亂政時的第一強人,此後如有(包括百大風雲人物)何振梁、蔣介石、馮玉祥、宋美齡、陳誠、吳國楨、毛澤東、周恩來、鄧小平、林彪、江青、李嘉誠、李登輝、楊振寧、達賴喇嘛十四世、傅成裕、章子怡、王建民、鞏莉、王維林、薄熙來、李娜、蔡英文等。年度風雲人物除了蔣及宋夫婦,還有鄧小平和何大一,時代雜誌的創辦人之一Henry Ruce就是在山東煙台登州出生,因此這本風格上一直有中國情結,甚至和蔣關係緊密而有反共基督情緒,相較下時代雜誌主觀許多,在美國尼克森總統訪華後態度也轉變,對於北京和華府的正式外交往來轉正面積極。經濟學人對中國比日本還要重視,就在日本1968年超越西德後壓倒性主導全球經濟後,雜誌並沒有獨立日本專欄於亞洲版以外,而日本這三四十年來政治家、財閥大老、學者和影視名人輩出數百名,勝於今天習近平及馬雲的能力與權勢,今天比較起來兩岸三地在李嘉誠之後也才多幾個,如郭台銘和兩岸2000年以來大概十個不到政要而已,就學問及研究性方面而言,馬雲和雷軍是否仍為表率現在還有問題。筆者當年希望延續之前萊曼兄弟的問題是早在2003年就被預測出可能的金融機制弱點,或稱大抉口之處,來分析中國黨政及經濟情勢,莫忘自由貿易對世界經濟的重要性。 筆者從此每週會詳細看除了Banyan即紙本Asia欄之外,就是這天新成立的Analect版China欄至今年的二月左右,每個禮拜文章幾乎不俗,社會面和政治面分析得都很透澈,包括香港的相關文章有時也是在China欄出現,而台灣方面的討論仍然在Asia欄內,以及中國正在成長的跨國企業及經濟情勢有的還是在Business的Schumpeter及Finance & Economics 的Buttonwood出現。筆者的文章此後,北京中央的要員是會過目的,大部份是亞洲企業、中日韓三國和一些東南亞的新聞,以及寫Books & Arts的歷史研究與新書書評,而台灣這邊的要聞和即時狀況是在兩年後的2014舊曆年後,因故(很討厭好幾年的台灣社會)跑去看東森新聞頻道,才比較恢復閱報習慣,就悶著寫,北京的中共領導的聲音和政治對筆者來講比較有歸屬感吧~而又過了好幾年了。 |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |