字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/05 09:41:30瀏覽19|回應0|推薦0 | |

Japan’s hiring practicesHello world Japanese firms are waking up to the merits of hiring globe-trotting recruitsAug 27th 2011 | TOKYO | from the print edition

RYOSUKE KOBAYASHI is the only Japanese undergraduate in his year at Harvard University. When he applied, he knew no one who could advise him on how to get in. So this week, in a rickety wooden inn in Tokyo, sitting cross-legged on tatamimats with Apple Macs on their laps, he and fellow Harvard students conducted seminars for Japanese high-school students on subjects ranging from animeto Thomas Hobbes. He was not encouraging students to go to America, he insists, just offering them an alternative to uchimuki, or the culture of looking inward, which pervades Japan. For example, in 1997 there were roughly equal numbers of Japanese, Korean and Chinese students at Harvard, including postgraduates. Now there are five times as many Chinese as Japanese, and three times as many Koreans. The story is similar at other foreign universities. Meanwhile, Japanese firms have lost ground to their Chinese and South Korean rivals. Some say this is no coincidence. Yasuyuki Nambu, the boss of Pasona, a Tokyo-based recruitment consultancy, says Japanese universities churn out students for old-fashioned businesses, rather than fast-growing global ones such as IT and retail. Japan Inc needs more creative thinkers and linguists. So several firms are courting young Japanese who have been abroad. In this section · The minister of magic steps down · »Hello world Jobs fairs for those who have studied abroad are suddenly popular. Mynavi, the sponsor of one, says the number of participating firms soared by almost 50% since last year, to 188. Keidanren, Japan’s big-business lobby, has promised to hold a special jobs exchange for students returning from abroad next summer, tacitly admitting that Japan’s traditional hiring schedule hobbles them: people are recruited in Japan to start work in April, which is during the academic year in America and Europe. The University of Tokyo, Japan’s best, is mulling starting in September instead, to fit in with the rest of the world. In other countries there has long been a market for footloose talent. But in Japan students usually have just one shot at securing a steady first-time job: in their third year at university. If they are abroad, they miss it, and may have to study an extra year in Japan to earn their chance. That has discouraged people from studying abroad. And corporate culture in Japan has tended to favour those who follow the rules: training is done “on-the-job”, which implies little respect for what was learned at college. Pasona reckons the change has accelerated since March, when Japan was hit by an earthquake that disrupted the nation’s supply chains and power plants. The population is ageing and shrinking; to avoid shrinking with it, Japanese firms must expand overseas. Recent months have seen a surge of foreign mergers and acquisitions. But while hiring trends may have started to reflect this shift, corporate culture has not. Hierarchy and pay remain rigid in many Japanese firms–you do what you are told and get what you are given. Well-travelled recruits may not like this. And if they don’t, they can go elsewhere. from the print edition | Business · Recommended · 30 Hello world Sep 1st 2011, 18:04

Look at these graduates full of vitality and know-how!

Compared with other big economy in Asia, Japanese still the top leader of innovation of IT or retail. Not only Japan’s enterpreneuer but also China’s tend to hire Japanese graduates. I recently chat with some prominent business leaders, requesting for their next action of expanding their territory as fast as Chinese People’s Liberation Army. One of them disclose the similar thinkings that they want to hire foreigners speeding up efficiency and wider range of sight.

It had been for a long time that the employee was hired by just one employer in all of his life “for once and all” from the end of World War II to Shinzo Abe couple’s inauguration. Apperant after 2007, Japan’s bussiness didn’t follow this custom and begin to be pressured by the near Asian growing business. One of the result is sure to re- evaluate the aspect of human resource. Meanwhile, new thinkings among the about 25-year-old generation are emerging, including the reflection of Japan’s history from 1868’s Meiji-restoration to the present of leaderless DPJ, and the understandings of BRIC’s rapid development. Accompanying the suffering of the age of the aged society, it is very hard for this country’s younger to choose “earlier going to be employed and earn their livings” or “more study or harder research than other in your life of university”.

Still, there are numerous business especially international consortiums advancing and leading innovation in the world. They are turning the startegies to the adjustment of supply-demand chain. For example, Uniqlo’s Tadashi Yanai is about to open the historic largest branch in New York to compete with Europe and America’s business. The next step of these conglomerates is to manage the risk of allocation. The consideration of this hiring practice doesn’t really mean the rest of Asian younger has more possibilities than Japanese. And traditionally thinking, Japan’s these big companies still use Tokyo University’s graduates first to keep the high quality, the high-rise building in Tokyo’s Ginza and the price of top brand so that I can continuously purchase the merchandise of Fujio’s Canon, Wada Kovo’s SONY, Norio Sasaki’s Toshiba, Yamamoto’s Fujitsu and listen to the disc of avex’s Ayumi Hamasaki and Ai Otsuka.

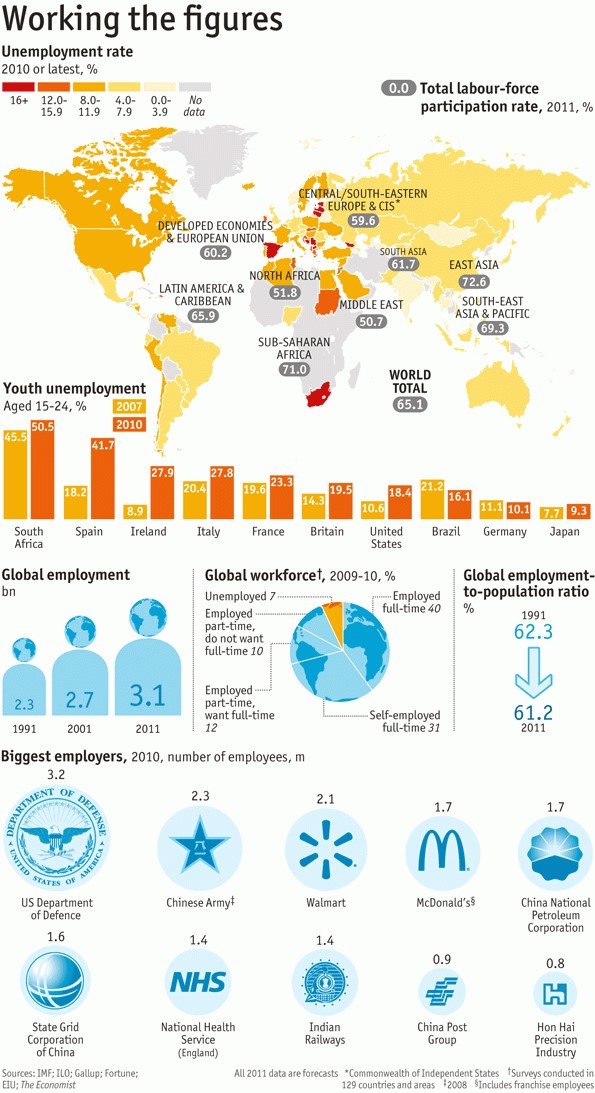

Recommended 8 Report Permalink 日本的年青活力的探討,基本上雖然通貨緊縮有,但是日本高等教育品質及年青20-30歲失業率的指標很良好,年輕人非得要海外工作像過幾年的台灣或南韓的情況不嚴重。那週日本首富柳井正的優衣庫在世界最大坪數的分店要在紐約市開張了,顯然日本企業的前景仍然很遠很好,繼續在世界各地擴大貿易。加上不差的基礎教育及世界常識與民族性,東京銀座仍居亞洲的地王。日本的企業領導雖然稍不比美國的智力與活力,但是老練及剛強個性挺住萊曼兄弟危機,相對上過幾年內國際間尋求hedge fund的時候,看上日本金融業的安定,會來日本作投資理財規畫,較為穩妥。日本的流行音樂以愛貝克思為首的濱崎步、安室奈美惠及大塚愛仍然主導亞洲流行音樂。雖然原來經濟學人的照片,日本東京大學畢業的年輕人還是有傳統束祔,至少願意放手一試,哈日風在世界各地仍然未衰。後來大塚愛還有Hello New Me的歌~每天日本的早安元氣十足在安倍晉三的兩次三支箭有了推陳出新。 以下這篇是經濟學者雜誌當年度很棒的特別報導,這篇筆者有作很深刻的心得,不過沒有貼出來,就不在這裡多說了。雖然這篇的主題因為工作無人化、機器人化及工作性質本身又因開發作了分化,世界的供應鏈也因數場政局變遷及經濟此消比長作了移位,但是原則到了七八年後的今天仍然大體適用。這篇筆者曾經拿給當時國務院的副總理李克強和總理溫家寶看過,從第二個圖表統計世界前十多人口組織,後來這給中共中央作了多方面勞動政策的進化啟示,其中的國有企業的跨國化、全球化部局,主要是人事主管上參考依據。 Special report: The future of jobsIn this special report · The great mismatch The great mismatch In the new world of work, unemployment is high yet skilled and talented people are in short supply. Matthew Bishop explainsSep 10th 2011 | from the print edition

“FAR AND AWAY the best prize that life offers is the chance to work hard at work worth doing,” observed Theodore Roosevelt, then America’s president, in a Labour day speech on September 7th 1903. Today the billions of people the world over who seek that prize are encountering simultaneous feast and famine. Even in developed economies that are currently struggling, many people, perhaps more than ever, are doing the job of their dreams, taking home both a good salary and a sense of having done something worthwhile. In booming emerging countries such as China and India, many at least have a better job than they ever thought possible. Yet at the same time in much of the world unemployment is persistently high and many of the jobs on offer are badly paid, onerous and unsatisfying. This has serious political implications, not least for America’s current president, Barack Obama, who risks losing his own dream job because of his perceived failure to have created enough work for his fellow citizens. As Mr Obama entered the White House in January 2009, the country’s unemployment rate was about to climb above 8%, up from around 5% a year earlier. It has not recovered since and is currently around 9%. Until the presidential election in November next year Mr Obama is likely to be dogged by the phrase “jobless recovery”—always assuming that the recovery does not double-dip into an even more jobless recession. In this special report · »The great mismatch Much as Americans complain, compared with some other countries their economy presents a picture of good health. In the weaker economies of the euro zone, jobs have been sacrificed in the name of austerity, especially in the public sector, to avoid defaulting on debts built up by free-spending governments. Anger at high unemployment has caused unrest and may have been a contributory factor in the riots in Britain last month. In late July thousands of unemployed young Spaniards, known as los indignados(the indignant), having protested in cities across their own country, began a long march to Brussels to draw attention to the shockingly high jobless rate of over 40% among their age group.

Outside the rich world, the Arab Spring that brought down the governments of Tunisia and Egypt earlier this year was triggered in part by the lack of decent work for young people. Even in booming China and India policymakers worry about how to ensure there are enough decent jobs, especially for young people and graduates. Both countries still have hundreds of millions of people living in abject poverty, especially in rural areas. A good job would be the best way out. Yet even as many people face a job famine, a minority is benefiting from an intensifying war for talent. That minority is well placed to demand interesting and fulfilling work and set its own terms and conditions. But above all the pay of such people—from executives to investment bankers and software engineers in Silicon Valley—is soaring. The most talented increasingly get a multiple of the salary of the average performer. This has led to rising inequality in incomes in many countries which may be increasing social tensions. Mr Obama can reasonably point out that he was elected in the wake of a financial meltdown that had threatened to bring about another Great Depression, with an unemployment rate that would make the current one look like a lucky escape. The co-ordinated global stimulus by members of the G20 in 2009, though far from perfect, helped save the world from something much worse—though that probably provides little comfort to the 205m people round the globe who are now unemployed. Nor is there much scope for further stimulus. But today’s jobs pain is about more than the aftermath of the financial crisis. Globalisation and technological innovation are bringing about long-term changes in the world economy that are altering the structure of the labour market. As a result, unemployment is likely to remain high in the rich economies even as it falls in the poorer ones. Edmund Phelps, a Nobel prize-winning economist, thinks that in America the “natural rate” of unemployment (below which higher demand would push up inflation) in the medium term is now around 7.5%, significantly higher than only a few years ago. Michael Spence, another Nobel prize-winning economist, in a recent article in Foreign Affairsagrees that technology is hitting jobs in America and other rich countries, but argues that globalisation is the more potent factor. Some 98% of the 27m net new jobs created in America between 1990 and 2008 were in the non-tradable sector of the economy, which remains relatively untouched by globalisation, and especially in government and health care—the first of which, at least, seems unlikely to generate many new jobs in the foreseeable future. At the same time, says Mr Spence, the mix of jobs available to Americans in the tradable sector (including manufacturing) that serves global markets is shifting rapidly, with a growing share of the positions suitable only for skilled and educated people. Fear of continuing high unemployment also made a bestseller of Tyler Cowen’s book, “The Great Stagnation: How America Ate All the Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History, Got Sick, and Will (Eventually) Feel Better”. It argues that for much of its history America (and to some extent other rich countries) enjoyed the benefits of free land, lots of immigrant labour and powerful new technologies. But over the past 40 years these advantages have faded and America has found itself on a technological plateau, he says. To the obvious question about the internet, he retorts that the web has provided lots of utility for users but much less in the way of profits—and relatively few new jobs. Lowering this new natural rate of unemployment will require structural reforms, such as changing education to ensure that people enter work equipped with the sort of skills firms are willing to fight over, adjusting the tax system and modernising the welfare safety net, and more broadly creating a climate conducive to entrepreneurship and innovation. None of these reforms is easy, and all will take time to produce results, but governments around the world should press ahead with them. As this special report will explain, the changes now under way will pose huge challenges not only to governments but also to employers and individual workers. Yet they also have the potential to create many new jobs and substantial new wealth. To understand why these changes are so exciting for some people and so scary for others, a good place to start is the oConomy section on the website of oDesk, one of several booming online marketplaces for freelance workers. In July some 250,000 firms paid some 1.3m registered contractors who ply their trade there for over 1.8m hours of work, nearly twice as many as a year earlier. ODesk, founded in Silicon Valley in 2003, is a “game-changer”, says Gary Swart, its chief executive. His marketplace takes outsourcing, widely adopted by big business over the past decade, to the level of the individual worker. According to Mr Swart, this “labour as a service” suits both employers, who can have workers on tap whenever they need them, and employees, who can earn money without the hassle of working for a big company, or even of leaving home. It is still small, but oDesk shows how globalisation and innovation in information technology, the two big trends that have been under way for some time, are moving the world nearer to a single market for labour. Much of the work on oDesk comes from firms in rich economies and goes to people in developing countries, above all the Philippines and India. Getting a job done through oDesk can bring the cost down to as little as 10% of the usual rate. So the movement of work abroad in search of lower labour costs is no longer confined to manufacturing but now also includes white-collar jobs, from computer programming to copywriting and back-office legal tasks. That is likely to have a big impact on pay rates everywhere.

Who ate my job? This is causing alarm among middle-grade white-collar workers in the rich world, who saw what happened to manufacturing jobs in their economies. But workers in emerging markets who have those sorts of skills and qualifications are delighted. “I’m making in a week on oDesk what I made in a month as a schoolteacher, and I get to spend far more time with my family,” says Ayesha Sadaf Kamal, a freelance copywriter in Islamabad. Conversely, Janet Vetter, who used to have a full-time job as a copywriter for a magazine in New York, lost her job and now moves between part-time and freelance work. “I feel isolated as a freelancer and have had no health insurance since the start of the year; it’s too expensive,” she says. It is tempting to think of the globalisation of the labour market as a zero-sum game in which Mrs Kamal in Pakistan is benefiting at the direct expense of Ms Vetter in America. But economists point out that such calculations suffer from the “lump of labour fallacy”—the belief that there is only a fixed amount of work to go round. A better explanation, they say, is the theory of comparative advantage, one of the least controversial ideas in economics, which suggests that free markets make the world better off because everyone can concentrate on doing what they are best at. A global labour market will not make every individual in the world better off: there will be losers as well as winners All the same, a global labour market will not make every individual in the world better off: there will be losers as well as winners, and they may put up stiff resistance to change if the losses prove too painful. For instance, total global GDP could double if all barriers to the free movement of labour were removed, argues Michael Clemens in a recent paper, “Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?”. Yet the political implications of such mass migration make it improbable that governments, especially in rich countries, would unconditionally open their doors. Compared with previous bursts of global integration and technological upheaval, the changes now taking place in the labour market may produce an unusually large number of losers, partly because they have coincided with a particularly deep recession and partly because they are happening exceptionally fast. The priority for policymakers must be to keep the number of losers as small as possible. This special report will look at what this new world of work means for individuals and what they can do to ensure they are on the winning side. It will also look at the challenges facing companies as they compete to recruit the best talent. And it will examine what governments can do, even in these tough economic times, to equip their citizens to claim the prize described by Mr Roosevelt—and to protect the losers. from the print edition | Special report · Recommended · 33 · inShare48

|

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |