字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2018/03/25 00:45:11瀏覽64|回應0|推薦0 | |

Special report: Nuclear energyThe dream that failedNuclear power will not go away, but its role may never be more than marginal, says Oliver MortonMar 10th 2012 | from the print edition

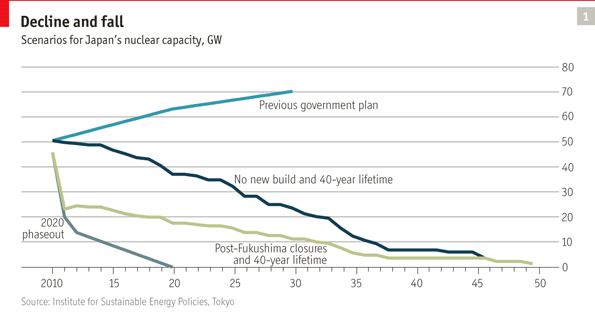

THE LIGHTS ARE not going off all over Japan, but the nuclear power plants are. Of the 54 reactors in those plants, with a combined capacity of 47.5 gigawatts (GW, a thousand megawatts), only two are operating today. A good dozen are unlikely ever to reopen: six at Fukushima Dai-ichi, which suffered a calamitous triple meltdown after an earthquake and tsunami on March 11th 2011 (pictured above), and others either too close to those reactors or now considered to be at risk of similar disaster. The rest, bar two, have shut down for maintenance or “stress tests” since the Fukushima accident and not yet been cleared to start up again. It is quite possible that none of them will get that permission before the two still running shut for scheduled maintenance by the end of April. Japan has been using nuclear power since the 1960s. In 2010 it got 30% of its electricity from nuclear plants. This spring it may well join the ranks of the 150 nations currently muddling through with all their atoms unsplit. If the shutdown happens, it will not be permanent; a good number of the reactors now closed are likely to be reopened. But it could still have symbolic importance. To do without something hitherto seen as a necessity opens the mind to new possibilities. Japan had previously expected its use of nuclear energy to increase somewhat. Now the share of nuclear power in Japan’s energy mix is more likely to shrink, and it could just vanish altogether. In this special report · »The dream that failed In most places any foretaste of that newly plausible future will barely be noticed. Bullet trains will flash on; flat panels will continue to shine; toilet seats will still warm up; factories will hum as they hummed before. Almost everywhere, when people reach for the light switches in their homes, the lights will come on. But not quite everywhere. In Futaba, Namie and Naraha the lights will stay off, and no factories will hum: not for want of power but for want of people. The 100,000 or so people that once lived in those and other towns close to the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant have been evacuated. Some 30,000 may never return. The triple meltdown at Fukushima a year ago was the world’s worst nuclear accident since the disaster at Chernobyl in the Ukraine in 1986. The damage extends far beyond a lost power station, a stricken operator (the Tokyo Electric Power Company, or Tepco) and an intense debate about the future of the nation’s nuclear power plants. It goes beyond the trillions of yen that will be needed for a decade-long effort to decommission the reactors and remove their wrecked cores, if indeed that proves possible, and the even greater sums that may be required for decontamination (which one expert, Tatsuhiko Kodama of Tokyo University, thinks could cost as much as ¥50 trillion, or $623 billion). It reaches deep into the lives of the displaced, and of those further afield who know they have been exposed to the fallout from the disaster. If it leads to a breakdown of the near-monopolies enjoyed by the country’s power companies, it will strike at some of the strongest complicities within the business-and-bureaucracy establishment.

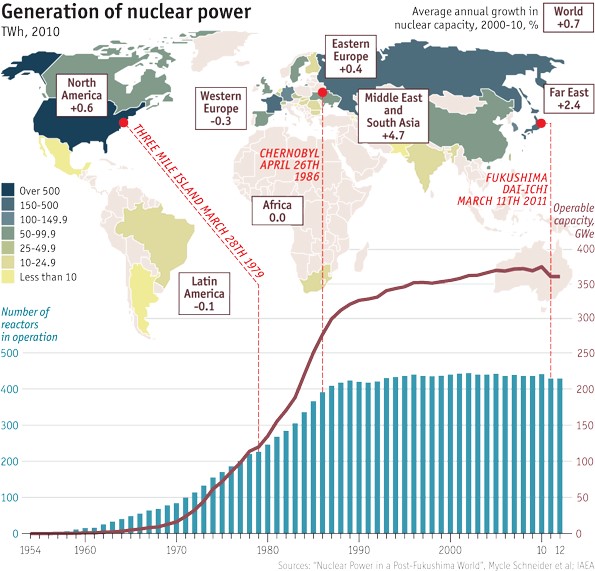

For parallels that do justice to the disaster, the Japanese find themselves reaching back to the second world war, otherwise seldom discussed: to the battle of Iwo Jima to describe the heroism of everyday workers abandoned by the officer class of company and government; to the imperial navy’s ill-judged infatuation with battleships, being likened to the establishment’s eagerness for ever more reactors; to the war as a whole as a measure of the sheer scale of the event. And, of course, to Hiroshima. Kiyoshi Kurokawa, an academic who is heading a commission investigating the disaster on behalf of the Japanese parliament, thinks that Fukushima has opened the way to a new scepticism about an ageing, dysfunctional status quo which could bring about a “third opening” of Japan comparable to the Meiji restoration and the American occupation after 1945. To the public at large, the history of nuclear power is mostly a history of accidents: Three Mile Island, the 1979 partial meltdown of a nuclear reactor in Pennsylvania caused by a faulty valve, which led to a small release of radioactivity and the temporary evacuation of the area; Chernobyl, the 1986 disaster in the Ukraine in which a chain reaction got out of control and a reactor blew up, spreading radioactive material far and wide; and now Fukushima. But the field has been shaped more by broad economic and strategic trends than sudden shocks. The renaissance that wasn’t America’s nuclear bubble burst not after the accident at Three Mile Island but five years before it. The French nuclear-power programme, the most ambitious by far of the 1980s, continued largely undisturbed after Chernobyl, though other countries did pull back. The West’s “nuclear renaissance” much bruited over the past decade, in part as a response to climate change, fizzled out well before the roofs blew off Fukushima’s first, third and fourth reactor buildings. Today’s most dramatic nuclear expansion, in China, may be tempered by Fukushima, but it will not be halted.

And if the blow is harder than the previous one, the recipient is less robust than it once was. In liberalised energy markets, building nuclear power plants is no longer a commercially feasible option: they are simply too expensive. Existing reactors can be run very profitably; their capacity can be upgraded and their lives extended. But forecast reductions in the capital costs of new reactors in America and Europe have failed to materialise and construction periods have lengthened. Nobody will now build one without some form of subsidy to finance it or a promise of a favourable deal for selling the electricity. And at the same time as the cost of new nuclear plants has become prohibitive in much of the world, worries about the dark side of nuclear power are resurgent, thanks to what is happening in Iran. Barring major technological developments, nuclear power will continue to be a creature of politics not economics. This will limit the overall size of the industry Nuclear proliferation has not gone as far or as fast as was feared in the 1960s. But it has proceeded, and it has done so hand in hand with nuclear power. There is only one state with nuclear weapons, Israel, that does not also have nuclear reactors to generate electricity. Only two non-European states with nuclear power stations, Japan and Mexico, have not at some point taken steps towards developing nuclear weapons, though most have pulled back before getting there. If proliferation is one reason for treating the spread of nuclear power with caution, renewable energy is another. In 2010 the world’s installed renewable electricity capacity outstripped its nuclear capacity for the first time. That does not mean that the world got as much energy from renewables as from nuclear; reactors run at up to 93% of their stated capacity whereas wind and solar tend to be closer to 20%. Renewables are intermittent and take up a lot of space: generating a gigawatt of electricity with wind takes hundreds of square kilometres, whereas a nuclear reactor with the same capacity will fit into a large industrial building. That may limit the contribution renewables can ultimately make to energy supply. Unsubsidised renewables can currently displace fossil fuels only in special circumstances. But nuclear energy, which has received large subsidies in the past, has not displaced much in the way of fossil fuels either. And nuclear is getting more expensive whereas renewables are getting cheaper.

Ulterior motives Nuclear power is not going to disappear. Germany, which in 2011 produced 5% of the world’s nuclear electricity, is abandoning it, as are some smaller countries. In Japan, and perhaps also in France, it looks likely to lose ground. But there will always be countries that find the technology attractive enough to make them willing to rearrange energy markets in its favour. If they have few indigenous energy resources, they may value, as Japan has done, the security offered by plants running on fuel that is cheap and easily stockpiled. Countries with existing nuclear capacity that do not share Germany’s deep nuclear unease or its enthusiasm for renewables may choose to buy new reactors to replace old ones, as Britain is seeking to do, to help with carbon emissions. Countries committed to proliferation, or at least interested in keeping that option open, will invest in nuclear, as may countries that find themselves with cash to spare and a wish to join what still looks like a technological premier league. Besides, nuclear plants are long-lived things. Today’s reactors were mostly designed for a 40-year life, but many of them are being allowed to increase it to 60. New reactor designs aim for a span of 60 years that might be extended to 80. Given that it takes a decade or so to go from deciding to build a reactor to feeding the resulting electricity into a grid, reactors being planned now may still be working in the early 22nd century.

Barring major technological developments, though, nuclear power will continue to be a creature of politics not economics, with any growth a function of political will or a side-effect of protecting electrical utilities from open competition. This will limit the overall size of the industry. In 2010 nuclear power provided 13% of the world’s electricity, down from 18% in 1996. A pre-Fukushima scenario from the International Energy Agency that allowed for a little more action on carbon dioxide than has yet been taken predicted a rise of about 70% in nuclear capacity between 2010 and 2035; since other generating capacity will be growing too, that would keep nuclear’s 13% share roughly constant. A more guarded IEA scenario has rich countries building no new reactors other than those already under construction, other countries achieving only half their currently stated targets (which in nuclear matters are hardly ever met) and regulators being less generous in extending the life of existing plants. On that basis the installed capacity goes down a little, and the share of the electricity market drops to 7%.

Explore our interactive guide to nuclear power around the world Developing nuclear plants only at the behest of government will also make it harder for the industry to improve its safety culture. Where a government is convinced of the need for nuclear power, it may well be less likely to regulate it in the stringent, independent way the technology demands. Governments favour nuclear power by limiting the liability of its operators. If they did not, the industry would surely founder. But a different risk arises from the fact that governments can change their minds. Germany’s plants are being shut down in response to an accident its industry had nothing to do with. Being hostage to distant events thus adds a hard-to-calculate systemic risk to nuclear development. The ability to split atoms and extract energy from them was one of the more remarkable scientific achievements of the 20th century, widely seen as world-changing. Intuitively one might expect such a scientific wonder either to sweep all before it or be renounced, rather than end up in a modest niche, at best stable, at worst dwindling. But if nuclear power teaches one lesson, it is to doubt all stories of technological determinism. It is not the essential nature of a technology that matters but its capacity to fit into the social, political and economic conditions of the day. If a technology fits into the human world in a way that gives it ever more scope for growth it can succeed beyond the dreams of its pioneers. The diesel engines that power the world’s shipping are an example; so are the artificial fertilisers that have allowed ever more people to be supplied by ever more productive farms, and the computers that make the world ever more hungry for yet more computing power.

The way the future was

There has been no such expansive setting for nuclear technologies. Their history has for the most part been one of concentration not expansion, of options being closed rather than opened. The history of nuclear weapons has been defined by avoiding their use and constraining the number of their possessors. Within countries they have concentrated power. As the American political commentator Gary Wills argues in his book, “Bomb Power”, the increased strategic role of the American presidency since 1945 stems in significant part from the way that nuclear weapons have redefined the role and power of the “commander-in-chief” (a term previously applied only in the context of the armed forces, not the nation as a whole) who has his finger on the button. In the energy world, nuclear has found its place nourishing technophile establishments like the “nuclear village” of vendors, bureaucrats, regulators and utilities in Japan whose lack of transparency and accountability did much to pave the way for Fukushima and the distrust that has followed in its wake. These political settings govern and limit what nuclear power can achieve. from the print edition | Special report The dream that failed Mar 11th 2012, 14:07

It has been far away since the occurence of last year’s 311 Earthquake of Eastern-Japan. There are numerous articles, reports, memorandum and rituals in any form reflects the deep consoles and the willingness to better future. Most of what people talk of is the dilemma of exercising nuclear power plant, although there is fewly mutual solution to health, safety and economical principle. After I read the leader column’s article and this special report, the following is what I feel pitious and I would like to suggest.

In mid-1990s, some French and German started a chant of anti-nuclear by practicing politics, improving education and seeking support of enterprises. In Japan, the discussion about nuclear power plant has been flourishing because Japanese wants to not only make inner economy progressive but also live at few risk of environment.

Japans Newton Magazine, which I had read for six years, once reported a series of nuclear power plant concerned. As reported, about Prime minister’s tenure of late Keizo Obuchi and Mori Yoshiro, Mr. Keizo once ensured the safety of all Japanese nuclear power plant. It is Fukushima Dai-ichi that Mr. Keizo had confidence in. And it was estimated that this could sustain a magnitude 7.0 earthquake.

The urge to rise the awareness of eco-friendly life is partly because a runaway chain reaction at a uranium processing plant in Japan’s Tokaimura, which exposed nearly 70 people to radiation on Sep. 30, 1999, was the biggest nuclear power accident, even the worlds worst, since the 1986 Chernobyl’s catastrophe. Then governing Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) had critically examined all power plants letting Japanese public opinion increase the attention to the safer nation.

That is to say, there should have been no more serious incident than Tokaimura’s after 1999. Japan, where earthquake often happens as well as famous for the outstanding technology, still suffer horribly; therefore, the decision about life without nuclear energy seems to be the right way. More importantly, bureacracy, researchers, workers in the plant, emergency helpers and ordinaries should know how to urgently react to both normal situation and the emergency.

Until the present, the serious outcome of Fukushima’s radiation exposure still remains. Several weeks ago, for an instance, Taiwan’s SETTV visited the three prefectures. And unfortunately when leaving for Fukushima city’s centre, their team bumped into a car accident on the country road. The managing editor Chen Ya-lin had stayed for 5 hours (more than 2 hours) testing the location with the highly dangerous 9 mSv more than the Japan’s standard of 2 mSv. Meanwhile, Taiwanese donates NTD. 2.5 bn, most of which is gradually allocated to reconstruct the surroundings, to the local Japanese miserable for a year, said by the singer Ong Chien-yu (Judy Ongg).

Last week in Taiwan’s Liberty Times, Liu Li-er, a travel writer in Japan, discussed Japanese view of nuclear power plant, referring to the changing right-hand activist’s thought of nuclear energy. Like Kobayashi Yoshinori, many these activists, who carry banners with slogans of traditional nationalism, patriotism and highly economic growth, now express attitude toward anti-nuclear energy one after one, having not thought anymore that this kind of energy is equal to the guarantee of economic growth.

As the Economist talked in this issue, indeed, nuclear energy concerned is classified as politics issue rather than other aspects. Almost of developed countries have abandoned the notion of pro-nuclear energy if only counting the cost to taxpayer for the establishment of more expensive nuclear power plant. The only exception is United States, whose president Barack Obama tried to recover the interior economy by building more nuclear power plant for lowering unemployment rate last year.

In comparison, the developing country such as China plans to own more nuclear energy. The buildup of Guangdong’s Dayawan Nuclear Power Plant was one of Deng Xiao-ping’s prominent policy. Like Dayawan, there are six exercising ones and twelve ones under construction in mainland China. All the nation becoming strong wealth results from the efficient way to earn money rather than any other including environmental protection. But, for the same reason, more Chinese enterprises invest more development of renewable energy. In either profitable or eco-friendly way, these developing countries now also have the eco-friendly awareness so that the cost of renewable energy decreases. The twelfth five-year plan contains the importance of economically environmental protection.

At the same time with my writing the above, Matsutoya Yumi’s “Haruyo, koi” (Coming in, Spring), chosen as one of songs in 2011’s 62th Kohaku Uta Gassen, may encourage Japanese as time goes by. The coming spring after the historically frozen winter in Japan tells people that the better life is worth chasing while balancing economics and the earth breathing forever.

Recommended 7 Report Permalink 筆者再回顧這篇時,隨興拿起中島美嘉的「櫻花紛飛時」,及「新音樂女王」松任谷由實及林亨柱的「春天●來吧」,這兩首相當於香港周華健的「花心」,春去春有回來之時,今天已是六年後的人間四月天,平凡而樸實的季節又一次的降臨人間。當年日本正逢311東日本大地震一週年,那一年間筆者透過日經中文網瞭解日本和中國相關經濟及大企業概況,偶爾還有社會面的新聞。 核能安全和經濟發展有一陣子是稍微對立的。筆者在這篇先回顧了1990年代中期興起的法德等國環保意識,後來在小渊惠三的任上曾有一起事故在1999年9月30日,照日本民族性應該有深究核能安全問題,但福島核災還是發生了。在這一年的思考中,根據劉黎兒曾經在自由時報投的稿,小林善紀這些日本強烈右翼已把永續家園列入愛國意識且高於經濟面,而在有能力維持和防災的前提,這重啟福島核電廠的問題仍然不得不往恢復供電的方向來走。這基礎建設的成本還是要照使用者付費來算。當時反觀美國本來也是重綠能家園的歐巴馬政府,因為萊曼兄弟的問題拖了經濟復甦,因此恢復核電廠的興建。 三立當時前總編輯陳雅琳,兼世新大學教授,前往附近作一週年回顧專題,在途中出車禍,趁員警處理現場時測到9毫西弗,高於日本政府標準2毫西弗甚多。至3月11日止,根據翁倩玉的說明,台灣人提供共新台幣25億的愛心捐款給日本政府。福島核災的食品安全至今仍然未平息,科學統計數據掩蓋不住真實案例和災民的長痛。筆者在此也有舉廣州大亞核能發電廠的例子,在這篇發表之後過了半年有一次原料外洩,還好沒有輻射洩出。這創百年紀錄的北極風暴給的嚴寒冬天也過了,在春意回暖大地時,寫這篇在經濟學人雜誌,希望日本當地的災民也看得到,能夠少一些恐懼,多一份信心。 *錄自Claude Debussy德布西的「Debussy: 3 Chansons de Charles dOrléans - 3. Yver, vous nestes quun vilian」的一段:「Salut, printemps」- Welcome, spring Welcome, spring, season of youth, God is giving the fields back their crown, the ardent sap begins to simmer, boils over and breaks free from its prison. The woods and fields are in flower, an invisible world is humming, the water flows over the ringing pebble, singing its clear song. Broom flowers turn the hillside gold, the snow of hawthorn blossom falls on to the green grass below; all is fresh growth, love, and light, and from the earths fertile breast rise up both songs and perfumes. Good morning, spring! Welcome, spring! *附當期Leader專欄相關文章一篇 Nuclear powerThe dream that failedA year after Fukushima, the future for nuclear power is not bright—for reasons of cost as much as safetyMar 10th 2012 | from the print edition

THE enormous power tucked away in the atomic nucleus, the chemist Frederick Soddy rhapsodised in 1908, could “transform a desert continent, thaw the frozen poles, and make the whole world one smiling Garden of Eden.” Militarily, that power has threatened the opposite, with its ability to make deserts out of gardens on an unparalleled scale. Idealists hoped that, in civil garb, it might redress the balance, providing a cheap, plentiful, reliable and safe source of electricity for centuries to come. But it has not. Nor does it soon seem likely to. Looking at nuclear power 26 years ago, this newspaper observed that the way forward for a somewhat moribund nuclear industry was “to get plenty of nuclear plants built, and then to accumulate, year after year, a record of no deaths, no serious accidents—and no dispute that the result is cheaper energy.” It was a fair assessment; but our conclusion that the industry was “safe as a chocolate factory” proved something of a hostage to fortune. Less than a month later one of the reactors at the Chernobyl plant in Ukraine ran out of control and exploded, killing the workers there at the time and some of those sent in to clean up afterwards, spreading contamination far and wide, leaving a swathe of countryside uninhabitable and tens of thousands banished from their homes. The harm done by radiation remains unknown to this day; the stress and anguish of the displaced has been plain to see. In this section · »The dream that failed Et tu, Japan Then, 25 years later, when enough time had passed for some to be talking of a “nuclear renaissance”, it happened again (see article). The bureaucrats, politicians and industrialists of what has been called Japan’s “nuclear village” were not unaccountable apparatchiks in a decaying authoritarian state like those that bore the guilt of Chernobyl; they had responsibilities to voters, to shareholders, to society. And still they allowed their enthusiasm for nuclear power to shelter weak regulation, safety systems that failed to work and a culpable ignorance of the tectonic risks the reactors faced, all the while blithely promulgating a myth of nuclear safety. Not all democracies do things so poorly. But nuclear power is about to become less and less a creature of democracies. The biggest investment in it on the horizon is in China—not because China is taking a great bet on nuclear, but because even a modest level of interest in such a huge economy is big by the standards of almost everyone else. China’s regulatory system is likely to be overhauled in response to Fukushima. Some of its new plants are of the most modern, and purportedly safest, design. But safety requires more than good engineering. It takes independent regulation, and a meticulous, self-critical safety culture that endlessly searches for risks it might have missed. These are not things that China (or Russia, which also plans to build a fair few plants) has yet shown it can provide. In any country independent regulation is harder when the industry being regulated exists largely by government fiat. Yet, as our special report this week explains, without governments private companies would simply not choose to build nuclear-power plants. This is in part because of the risks they face from local opposition and changes in government policy (seeing Germany’s nuclear-power stations, which the government had until then seen as safe, shut down after Fukushima sent a chilling message to the industry). But it is mostly because reactors are very expensive indeed. Lower capital costs once claimed for modern post-Chernobyl designs have not materialised. The few new reactors being built in Europe are far over their already big budgets. And in America, home to the world’s largest nuclear fleet, shale gas has slashed the costs of one of the alternatives; new nuclear plants are likely only in still-regulated electricity markets such as those of the south-east. A technology for a more expensive world For nuclear to play a greater role, either it must get cheaper or other ways of generating electricity must get more expensive. In theory, the second option looks promising: the damage done to the environment by fossil fuels is currently not paid for. Putting a price on carbon emissions that recognises the risk to the climate would drive up fossil-fuel costs. We have long argued for introducing a carbon tax (and getting rid of energy subsidies). But in practice carbon prices are unlikely to justify nuclear. Britain’s proposed carbon floor price—the equivalent in 2020 of €30 ($42) a tonne in 2009 prices, roughly four times the current price in Europe’s carbon market—is designed to make nuclear investment enticing enough for a couple of new plants to be built. Even so, it appears that other inducements will be needed. There is little sign, as yet, that a price high enough to matter can be set and sustained anywhere.

Whether it comes to benefit from carbon pricing or not, nuclear power would be more competitive if it were cheaper. Yet despite generous government research-and-development programmes stretching back decades, this does not look likely. Innovation tends to thrive where many designs can compete against each other, where newcomers can get into the game easily, where regulation is light. Some renewable-energy technologies meet these criteria, and are getting cheaper as a result. But there is no obvious way for nuclear power to do so. Proponents say small, mass-produced reactors would avoid some of the problems of today’s behemoths. But for true innovation such reactors would need a large market in which to compete against each other. Such a market does not exist. Nuclear innovation is still possible, but it will not happen apace: whales evolve slower than fruit flies. This does not mean nuclear power will suddenly go away. Reactors bought today may end up operating into the 22nd century, and decommissioning well-regulated reactors that have been paid for when they have years to run—as Germany did—makes little sense. Some countries with worries about the security of other energy supplies will keep building them, as may countries with an eye on either building, or having the wherewithal to build, nuclear weapons. And if the prices of fossil fuels rise and stay high, through scarcity or tax, nuclear may charm again. But the promise of a global transformation is gone. from the print edition | Leaders *附雜誌數週後相關文章一篇 Post-crisis JapanLingering agonyApr 24th 2012, 6:50 by H.T. | NIHONMATSU

“THEY can’t be Japanese!” a journalist from Tokyo whispered caustically into your correspondent’s ear on hearing the uncharacteristic volume of shouting and heckling at a well-attended town-hall meeting. This past weekend, the Japanese parliament’s Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission held a two-day hearing for villagers of Namie and Okuma, two of the evacuated towns close to the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear-power plant, which suffered a triple meltdown in March last year. On April 21st the Namie residents in Nihonmatsu, where they have been relocated since the evacuation, were shockingly outspoken. More than 13 months after the disaster, much of the news interest in Fukushima has faded. But the agony of evacuation, and the sense of helplessness and frustration that it has spawned, remain palpable. The testimony of Namie city officials, who complained repeatedly about the lack of official information they were given as radiation levels increased during the disaster, is available online. But ordinary villagers made particularly pertinent points about the after-effects. First, they demanded clarity on the safe level of radiation exposure, especially for children and pregnant mothers. The government has allowed the residents of some evacuated municipalities to return to areas where the annual dosage is 20 millisieverts (ie 20 mSv) or below, pending further efforts at decontamination. It has also said that some displaced residents will be able to return home during the day even where the dosage is up to 50 mSv/year. But for those with children, there remain stubborn doubts about the long-term health effects of living under such dosages. Such places include Nihonmatsu, to where many of Namie’s children have been evacuated. Radiation there, in some areas, is in the range of 5 mSv/year or higher (they have been checked only sporadically). The International Commission on Radiological Protection says an appropriate “normal” level is 1mSv/year, over the long term. Second, some asked the national government to exempt all evacuees from the cost of their medical checks, not just the under-18-year-olds, as was apparently offered. It was noted that it might take years for cancers to develop, if they do at all, by which time many of the children who were exposed to radiation after the accident would be over 18. There was widespread support for an idea, pushed by Namie officials, to give everyone books to keep track of their health history. It’s astounding this has not been done already. Third, one Namie man made the point that the government provides insufficient support to those evacuees who are living in rented housing, as opposed to temporary accommodation. He said the aid for those assigned to temporary housing was mandated by law following the 1995 Kobe earthquake. But the law had not been changed to reflect the fact that many of the 100,000 or so nuclear evacuees have rented homes for themselves, instead of moving into temporary accommodation—because they know their evacuation will be permanent. Fourth, there was widespread condemnation of a decision by the prime minister, Yoshihiko Noda, to press for the restart of suspended nuclear reactors in other parts of Japan, even before the various accident-investigation commissions had finished their work. Some people at the meeting said this was a clear sign the government had forgotten the toll the accident had taken on their lives; the sense of being considered expendable ran through much of the hearing. “We have been mentally, spiritually and morally destroyed,” shouted one man to loud applause. He said the only way parliament could be reminded of how badly their lives were affected would be to move the Diet to the radiated zone near Fukushima Dai-ichi. That recommendation will no doubt be omitted from the independent investigation’s final report. But it sums up how badly the people of Namie feel they have been abandoned by the central government—and that holds true for many elsewhere from within the nuclear-evacuation zone, too. In their outspoken anger, they may not sound very Japanese. But some wonder whether the government remembers they are citizens of Japan at all. (Picture credit: Yoshikazu Tsuno / AFP) |

|

| ( 心情隨筆|心情日記 ) |