字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2007/02/23 18:19:12瀏覽936|回應0|推薦0 | |

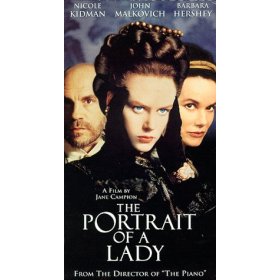

Horne, Philip. “Henry James: Varieties of Cinematic Experience.” Henry James on Stage and Screen. Ed. John R. Bradley. There is a better and more passionate fidelity, at a cost, in Jane Campion’s flawed, lugubrious, often gloriously beautiful The Portrait of a Lady (1996). Among those who know the book, the film is notorious for its deviations: the voices and images of modern Australian girls in a prologue, talking about love and kissing, or the three-in-a-bed sexual fantasy the heroine is given, at the end of which her suitors dematerialize a la ‘Star Trek’. But Laura Jones’s shooting script (published by Penguin) remains for the most part scrupulously close to James’s dialogue, and even to that of his more elaborate revised edition. Perversely, after all the care and imagination poured into sets, locations, costumes and manners, the effort of exactly recreating a physical, historical world, Jane Campion seems to have given the actors their head in gestural improvisation – with awkward results. For it is an anachronism (as well as a social solecism) when Nicole Kidman, a finely serious though not radiant Isabel, chatting to her cousin Ralph Touchett (a wonderful Martin Donovan) after a day out in London, takes off her boot, sticks her nose in it and sniffs. Portrait of a lady? P( 41) A more serious problem is the physical abuse Isabel suffers late in the film (not in book or shooting script) at the hands of her elegantly cruel husband Gilbert Osmond (John Malkovich), when she opposes him. To have Osmond go so far beyond the maliciously calculated mind-games at which he is expert as to rap her knuckles, trip her on a marble floor and –bizarrely-grind his head into her temples, is to play up the scene at the cost of the story. As a battered wife, Isabel (who weeps in nearly every scene) is instantly justified in rebelling, like In James, Isabel faces an ethical dilemma alongside her complex psychological compulsions; in the film, Campion’s masochistic reading of Isabel’s choice of Osmond empties out the debate and unbalances the drama (she seems to have been influenced by Alfred Habegger’s strong reading in Henry James and the ‘Woman Business’ [1989]). 22 The dying Ralph here hardly could tell Isabel (as in James) that Osmond ‘was greatly in love with you’. 23 It would be a richer film if he could have; Malkovich gives us instead one of his insolent villains, and it is a shame that William Hurt, who can convincingly do likeability as well as cold selfishness, did not, as originally intended, play the part.24 P( 42)

|

|

| ( 知識學習|語言 ) |