字體:小 中 大

字體:小 中 大 |

|

|

|

| 2007/01/24 15:13:52瀏覽362|回應0|推薦0 | |

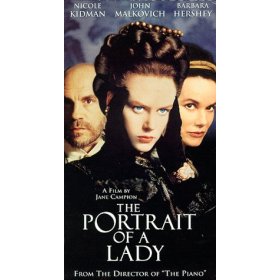

Lodge, David. Consciousness and the Novel. “Henry James and the Movies.” HENRY JAMES & THE MOVIES The heroine of the hit romantic comedy of 1999, Notting Hill, is an American movie star who comes to The usual explanation for this phenomenon is that James is the new Jane Austen—that the vogue for his novels in the movie world was triggered by the success of Sense and Sensibility and Emma. But there were several earlier movie adaptations of James’s fiction. In 1974 there was Daisy Miller, directed by Peter Bogdanovich. The Merchant-Ivory team made The Europeans in 1979 and The Bostonians in 1984. There have been three film versions of The Turn of the Screw, most recently one in 1992 which updates the action to the 1960s. And going even further back, there was a film of Over the same period there were several television adaptations of James’s books, especially in That Henry James’s novels should be so popular with modern filmmakers is both ironic and paradoxical. It is ironic because throughout his literary career James hankered after a great popular and commercial success, and never achieved it. His novels never sold in great quantities, and his effort to become a stage dramatist ended in disaster after a few attempts, when he was booed by the gallery on the first night of Guy Domville in 1895, the most humiliating event of his literary career. In his lifetime he was revered by other writers and the more discriminating critics, but was never a best-seller, or anything like one. In recent times, however, his work has reached millions of people all around the world through the medium of the most popular all around the world through the medium of the most popular and democratic art form of the twentieth century—the cinema. James was an uncompromisingly highbrow writer, an innovator in form, whose works, particularly the later ones, are difficult and demanding even for well-educated readers. He was one of the founding fathers of the modern or modernist novel, which is characterized by obscurity, ambiguity, and the presentation of experience as perceived by characters whose vision is limited or unreliable. These are not the usual ingredients of best-selling fiction—and they are equally alien to the cinema. This is why the popularity of James’s books with modern filmmakers is paradoxical as well as ironic. Henry James was supremely a novelist of consciousness. Consciousness was his subject: how individuals privately interpret the would, and often get it wrong; how the minds of sensitive, intelligent individuals are forever analysing, interpreting, anticipating, suspecting, and questioning their own motives and those of others. And consciousness of this kind, which is self-consciousness, is precisely what film as a medium finds most difficult to represent, because it is not visible. If you make the characters put their thoughts into speech, you destroy the essential feature of consciousness in James’s would-picture—its private, secret nature; if you have the characters articulate their thoughts in voice-over monologue, you go against the grain of the medium and produce an artificial, intrusive effect. Facial expression, body language, visual imagery, and music can all be powerfully expressive, but they lack precision and discrimination. They deal in broad basic emotions: fear, desire, joy. James’s fiction, by contrast, is full of the finest, subtlest psychological discriminations. An example: in chapter 41 of The Portrait of a Lady, Gilbert Osmond is discussing with his wife, Isabel, Lord Warburton’s interest in his young daughter, Pansy. Relations between Isabel and her husband are already bad by this point in the story. Osmond says: “My daughter has only to sit perfectly quiet to become Lady Warburton.” “Should you like that?” Isabel asked with a simplicity which was not so affected as it may appear. She was resolved to assume nothing, for Osmond had a way of unexpectedly turning her assumptions against her. The intensity with which he would like his daughter to become Lady Warburton had been the very basis of her own recent reflections. But that was for herself; she would recognize nothing until Osmond should have put it into words; she would not take for granted with him that he thought Lord Warburton a prize worth an amount of effort that was unusual among the Osmonds. It was Gilbert’s constant intimation that for him nothing in life was a prize; that he treated as from equal to equal with the most distinguished people in the world, and that his daughter had only to look about her to pick out a prince. It cost him therefore a lapse from consistency to say explicitly that he yearned for Lord Warburton and that if this nobleman should escape his equivalent might not be found; with which moreover it was another of his customary implications that he was never inconsistent. He would have liked his wife to glide over the point. But strangely enough, now that she was face to face with him and although an hour before she had almost invented a scheme for pleasing him, Isabel was not accommodating, would not glide. And yet she knew exactly the effect on his mind of her question: it would operate as an humiliation. Never mind; he was terribly capable of humiliating her—all the more so that he was also capable of waiting for great opportunities and of showing sometimes an almost unaccountable indifference to small ones. Isabel perhaps took a small opportunity because she would not have availed herself of a great one. Osmond at present acquitted himself very honourably. “I should like it extremely; it would be a great marriage.” The corresponding passage in the screenplay of the 1996 film reads simply: OSMOND: You see, I believe my daughter only has to sit perfectly quiet to become Lady Warburton. ISABEL: Should you like that? OSMOND: I should like it extremely. The long paragraph interpolated between Isabel’s question and Osmond’s answer in the novel is an extraordinarily subtle analysis of the games unhappily married people play when they talk to each other. Isabel pretends not to know how intensely Osmond desires the match in order to make him admit it and thus expose his own pretence of being aloof from such social vanities. This, we are reminded, is only one episode in the long war of attrition, of move and countermove, that their marriage has become. And although Isabel is the weaker party in this struggle, we see hat she has learned, as it were, to fight dirty; she has learned how to dissemble for the sake of a small conversational advantage. Osmond, however, escapes by an unusual and graceful display of honesty: “I should like it extremely.” James’s dialogue is faithfully reproduced in the film, but there is absolutely no way the actors in the film could convey the content of Isabel’s unvoiced thoughts or those she imputes to Gilbert Osmond in the text. Here is a second example, this time from Merchant-Ivory’s The Bostonians, one of the most faithful feature film adaptations of a James novel. The story concerns the women’s movement I in late nineteenth-century She knew, again, how noble and beautiful her scheme had been, but how it had all rested on an illusion, of which the very thought made her feel faint and sick. Then these feelings are overtaken by fears for Verena’s safety. Olive hurries back to the house and finds Verena returned, huddled on the sofa. She didn’t know what to make of her manner; she had never been like that before. She was unwilling to speak; she seemed crushed and humbled. This was the worst—if anything could be worse than what had gone before; and Olive took her hand with an irresistible impulse of compassion and reassurance. From the way it lay in her own she guessed her whole feeling—saw it was a kind of shame, shame for her weakness, her swift surrender, the insane gyration, in the morning. Verena expressed it by no protest and no explanation; she appeared not even to wish to hear the sound of her own voice. Her silence itself was an appeal—an appeal to Olive to ask no questions (she could trust her to inflict no spoken reproach); only to wait till she could lift up her head again. Olive understood, or thought she understood, and the woefulness of it all only seemed the deeper. She would just sit there and hold her hand; that was all she could do; they were beyond each other’s help in any other way now. Verena leaned her head back and closed her eyes, and for an hour, as nightfall settle in the room, neither of the young women spoke. Distinctly, it was a kind of shame. After a while the parlour-maid, very casual,…appeared on the threshold with a lamp; but Olive motioned her frantically away. She wished to keep the darkness. It was a kind of shame. In the film we have no way of knowing exactly what either woman is thinking at this or any other point in the whole sequence, which is almost entirely silent, without dialogue, interior monologue, or even music. Olive’s behaviour as she wanders along the shore expresses only anxiety about what has happened to Verena (she has a vision of the young girl’s body being washed ashore which makes the point, perhaps over-emphatically). We have no way of knowing that she is suffering bitter disillusionment, with women in general and with Verena in particular. Then when Olive returns home to find Verena there, her behaviour in the film expresses only relief, and a sudden release of sexual passion when she embraces Verena. The gesture of waving away the maidservant with the lamp is retained, but we have no way of knowing that this is to conceal Verena’s “shame.” The film is for the most part faithful to the novel in showing the episode from Olive’s point of view. But it does add a scene not in the book, in which we see Verena and Basil on the shore, beside a rowboat at the water’s edge. Verena, who has been wearing Basil’s jacket, gives it back to him, and he throws it into the boat in a gesture of frustration and defeat as she walks away. It is not at all clear whether they have just come back from a boat trip in the course of which Verena has told Basil that she does not love him, or whether she is refusing to go out in the boat with him, which he interprets as a gesture of rejection. In either case she appears to change her mind, runs back, and throws herself into his arms. They embrace passionately beside the breaking waves. The next we see of Verena (evidently some hours later, to judge by the change of light) she is discovered by Olive, huddled on the sofa looking traumatized. What has happened in the meantime to cause this extreme reaction? The embrace on the seashore doesn’t seem to account for it. If you didn’t know the book, and your Henry James, you might think that Verena had been a victim of date rape. I have given two examples where the film version cannot match the precision and subtlety of the representation of character and motive in the original novel simply because of the nature of the medium. So I come back to the question I raised earlier. Why have filmmakers been so attracted to James, when the difficulties of filming his work are so obvious and so formidable? There are several possible answers. Period or costume drama is popular with audiences, and the film industry is always looking for suitable books to adapt. Such films are expensive to make, because of all the historical detail that has to be recreated, but the works on which they are based are mostly out of copyright, so movie rights do not have to be paid for. James’s novels have great parts for American actors as well as British, which is important in an industry dominated financially by In his use of narrative, James was a transitional novelist, between the elaborately plotted novel of the high Victorian age—Dickens, Thackeray, George Eliot—and the modernist experimental novel of consciousness and the unconscious—Joyce, Woolf, Lawrence—in which plot is minimal. Commercial movies must have a strong narrative line. James’s novels do have stories with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and they are about subjects which have always fascinated movie makers and movie audiences: sexual desire and money, and the various ways in which these things can become intertwined. But James’s stories—even in the long novels—are fairly simple. There is not a lot of complication and subplotting. The essential narrative content of The Portrait of a Lady or The Wings of the Dove can be summarized, or “pitched” as they say in the movie industry, in a couple of sentences. This is an advantage in filmmaking. In adapting a Victorian classic, even as a TV mini-series, you have to discard a huge amount of plot, and a lot of characters. All you have to do with James is condense, and what gets left out is not narrative material, but psychological detail. The Portrait of a Lady is a very long novel—over 600 pages in my World’s Classics edition—but every significant character in it appears in the film, even (fleetingly) Henrietta Stackpole’s lover, Mr. Bantling. James was not an inherently cinematic novelist avant la lettre as, for example, Thomas Hardy was. James never describes situations of extreme physical jeopardy like that of Elfride and Knight on the cliff face in A Pair of Blue Eyes, nor visualizes a scene with the startling detail and unusual perspectives of Hardy’s authorial narrator. That doesn’t matter—the filmmaker can bring his own heightened visual effects to the story. James’s natural affinity was with the theatre, not with the new medium of moving pictures which emerged in the later part of his lifetime. He was a constant theatergoer and tried with very limited success to adapt his novels for the stage and to write original plays. This ambition is not surprising, because he was very good at dialogue—the dialogue of educated, upper-class people, mostly, but also on occasion lower-class American English—and he was good at imagining and orchestrating “scenes”—that is, people interacting in social situations, or confronting each other in private moments of conflict. He himself spoke of this as his “scenic method,” and attributed it to his long-standing interest in the theatre. In short, he wrote novels which are full of characters and scenes that can be performed, and which would positively invite performance if they weren’t so heavily enveloped in introspection and analysis. It is tempting for filmmakers to suppose, therefore, that all you have to do with a Henry James novel is strip out all the psychologising. Then you will be left with a strong story, some interesting characters, and a lot of good lines, which sounds like a recipe for a satisfactory film. But of course it is not as easy as that. Without the psychologising, the plots can seem melodramatic, or difficult to follow, or simply uninteresting. Transferred from the page to the screen, the original dialogue can seem artificial. Ironically (in view of James’s failure as a dramatist), his fiction—at least in the case of the shorter works—has transferred rather more readily to the stage than to the big screen: for example, The Heiress, the Aspern Papers, and The Turn of the Screw. On the stage, melodrama and artificiality are at home. For those who know and love the novels of Henry James, the movie adaptations will always be more or less disappointing, because of the medium’s inability to do justice to what is arguably the most important component of the books—their detailed and subtle representation of the inner life. Even those who do not know the novels may sense that something is lacking in these films, and wonder why anyone bothered to make them. It is no coincidence that the most critically admired film adaptation, The Europeans, was based on a little-known, relatively slight early work, essentially comic and satiric in tone, with a lot of dialogue and relatively little psychological analysis. Of the four recent major film adaptations, the most successful with film critics and the general public was The Wings of the Dove. It was also the one which took the most liberties with the original text and is therefore most likely to dissatisfy or outrage devoted readers of Henry James’s novels. The films of both The least satisfactory and least interesting of these films in my opinion is The heroine is played by Jennifer Jason Leigh, who is completely miscast in terms of the original novel. Catherine is described in the blurb on the back of the videotape box as “a lovely young woman.” The whole point of the story is that she is not lovely, and is entirely lacking in any other obvious charm. “A dull plain girl, she was called by critics,” says the narrator. She is not even interestingly ugly or disabled. She is “stolid,” strong and healthy. Clearly the film producers could not bring themselves to cast a genuinely plain actress. Jennifer Jason Leigh is good-looking in a rather gamine way, so to make sense of her part in the story she has to play the young Catherine as gauche to the point of imbecility. When she is introduced to Townsend at her cousin’s engagement party, she stares at him like a hypnotized rabbit, totally incapable of speech, creating an embarrassing scene. In the novel, however, the scene is described like this: Catherine, though she felt tongue-tied, was conscious of no embarrassment: it seemed proper that he should talk, and that she should simply look at him. What made it natural was that he was so handsome, or rather, as she phrased it to herself, so beautiful. (chapter4) The film also fudges the character of Townsend. In that scene of their fist meeting, he seems as spontaneously taken with Catherine as she is with him. IN the book it is obvious from the way he artfully ingratiates himself with Catherine’s aunt on the same occasion that he is already conducting a calculated campaign to marry Catherine. The film, however, encourages us to think that the genuinely loves Catherine as well as her money. In a crucial scene in the book Dr. Sloper goes to see Townsend’s sister, with whom he is living, to try to confirm his suspicions about the young man’s true character. It’s a brilliantly written scene in which the honest woman tries not to be disloyal to her brother, but cannot in the end conceal his unscrupulousness. Her final word, wrung from her by the force of Sloper’s personality, is “Don’t let her marry him!” and it settles and lingering doubts the reader may have about Sloper’s judgement of Townsend. In the film, this line is moved forward in the scene to become part of a passage of verbal fencing: Sloper says he doesn’t consider Townsend a fit husband for his daughter, and the sister says lightly, “then don’t let her marry him.” The climax of the scene in the film is an attack by the sister on Sloper for arrogant abuse of his power and wealth. What makes the character of Sloper so interesting is that he is absolutely right about Townsend, but absolutely wrong in the way he treats Catherine. By blurring the first point, the film turns his character into a stereotype of the repressive father. Both the screenplay and the direction move the story relentlessly towards cinematic cliché. So when Townsend finally breaks off the relationship and drives away from the distraught Catherine in a cab, of course it happens in pouring rain and of course Catherine, running after him, falls flat on her face in the muddy street. The final scene of the film is a particularly gross travesty of the original. In the novel, some years after the engagement was broken off by Townsend, and Sploer has died. He comes back, encouraged by Aunt Lavinia, to ask for a reconciliation, but Catherine, how has not married, tells him he has hurt her too much for her to consider such a thing. Townsend leaves, and in the last few lines there is an exchange between him and Aunt Lavinia in the hall that makes it clear he is as self-seeking as ever: “You will not despair—you will come back?” “Come back? Damnation!” And Morris townsend strode out of the house, leaving Mrs Penniman staring. Catherine meanwhile, in the parlour, picking up her morsel of fancy work, had seated herself with it again—for life, as it were. That is the last, eloquent line of the tale. In the film, Townsend calls on Catherine when she is teaching or entertaining a large group of little children (presumably in compensation for or sublimation of frustrated maternal instincts), who are removed so that the interview can take place. Catherine declines his offer. Townsend leaves, subdued, and we glimpse aunt Lavinia in the hall. There is no exchange of words between them. Catherine sits down at the piano; a little girl comes up and stands beside her, and smiles timidly. Catherine smiles back and continues to play. An operatic soprano sings an aria on the sound track, the background goes dark, Catherine plays on, and she gives a faint reminiscent smile. Blackout. The Portrait of a Lady is a more interesting failure. Great things were expected of it. It was directed by Jane Campion, the Australian director of that remarkable film, The Piano. It had a mouthwatering cast: Nicole Kidman, John Malkovich, Barbara Hershey, Martin Donovan, Shelley winters, Richard E. Grant, and Sir John Gielgud. Yet it was badly received by most of the critics. Here are some review quotes I gathered from the Internet: “It’s all surface and no depth. There’s no heart to this story…many of the set-ups just take too long, none of the complications inherent in the plot are shown clearly enough, none of the dialogue does enough to emphasise the real evil involved in manipulating people…Poor Henry James. I thought of him rolling in his grave, as I sat squirming in my seat.” “Campion has sacrificed sense to style, leaving powerful characters only vaguely explored in a story that should be based on emotions, not looks.”

“Very little of this tragedy makes it to our hearts as a result of an inept screen adaptation, inconsistent directing, meaningless camera angles and pointless closeups.” What went wrong? One might begin to answer that question by considering why Campion’s the Piano went right. It was a director’s film through and through. She herself wrote the script, which has relatively little dialogue (partly because the heroine is dumb) and tells a very simple story of basic emotions. The film makes its impact almost entirely by images—juxtapositions of culture and nature. Nobody who has seen the film will forget the opening scene of the piano being unloaded onto the surf-pounded beach, or the climax when the heroine in her Victorian clothing is dragged down into the depths of the sea, tethered to the piano. The Portrait of a Lady is a very different proposition: a classic novel, full of subtle psychological twists and turns, in which intense emotions are almost entirely concealed behind a surface of upper-class manners and polite conversation. The film certainly tries to be faithful to James’s novel—perhaps the screenplay, written by Laura Jones in collaboration with Campion, tries too hard in this respect. Of course they and to condense drastically, but most of the dialogue is actually James’s, and there is no significant deviation from the original story. However, Jones and Campion make spasmodic attempts to escape from this reverential approach with occasional sequences in quite different styles. The film begins with shots of a number of young women of the 1990s lying languorously around on the grass and then fades into a close-up of Nicole Kidman as Isabel—evidently a clumsy attempt to establish the “relevance” of the story to the present day. There is an erotic fantasy sequence in which Isabel imagines herself being caressed simultaneously by the three men who have at that stage been attracted to her—Ralph Touchett, Lord Warburton, and Caspar Goodwood. Isabel’s tour of the Some reviewers thought that John Malkovich played Gilbert Osmond as such a creepy, sinister character that it was impossible to believe that Isabel would marry him. But it has to be said that there is a certain weakness in the original novel here—James never really shows us Isabel’s moment of decision, of commitment to Osmond. We see her being quite plausibly attracted to his intelligence, culture, and polished manners; we see him call on her and make his proposal of marriage, which she does not accept or reject. She postpones an answer because she is going abroad. Osmond leaves, and James describes Isabel’s feelings thus: Her agitation…was very deep. What had happened was something that for a week past her imagination had been going forward to meet; but here, when it came, she stopped. The working of this young lady’s spirit was strange, and I can only give it to you as I see it, not hoping to make it seem altogether natural. Her imagination…hung back: there was a last vague space it couldn’t cross—a dusky, uncertain tract which looked ambiguous and even slightly treacherous. This “last vague space” is surely sexual, and it is not so much Isabel’s imagination that cannot cross it as James’s. He more or less admits as much, “not hoping to make it seem altogether natural.” Then there is a gap in the narrative, and the next time we see her she is engaged. There is never a moment in the text when Isabel acknowledges that she is “in love” with Osmond. Jane Campion has attempted to deal with this problem by suggesting that Osmond casts a kind of erotic spell over Isabel. She sets the proposal scene not in a drawing room, but in the crypt of the cathedral in The endings of James’s novels often raise problems for filmmakers because he favoured open or ambiguous endings, whereas the expectation of a classic period film, especially if it is a love story, is that it will have a closed and preferably happy ending. The fatuous ending of Washington Square, which tries to compensate Catherine for her spinsterhood with a vicarious family of adoring children, is a case in point. The film of The Portrait of a Lady is more satisfactory in this respect. In James’s novel, Caspar Goodwood makes a final appeal to Isabel to leave her hateful husband and live with him. She is tempted, but refuses. In the very last scene of the book, Henrietta Stackpole enigmatically urges Goodwood to “wait.” In the screenplay Laura Jones attempts a more affirmative, if no more cheerful, ending by making Isabel’s motive fro returning to The door opens. PORTRESS: A visitor to see you. Isabel comes into the room. The door shuts behind her. Isabel steps into the lamplight. Pansy looks at her as if at an apparition. Pansy’s voice out of the shadows: PANSY: You’ve come back. Isabel—eyes dazzled by light—finds it hard to see the girl in the shadows beyond the lamplight. ISABEL: Yes, I’ve come for you. She holds out her hand towards Pansy. Pansy sees Isabel’s hand, held out, in the brightest part of the light. The End Apparently this scene was shot, but not used (wisely, I believe). In the final editing Campion chose to end the film earlier than either screenplay or novel. Isabel has her final meeting with Caspar Goodwood in the snow-covered grounds of the Touchetts’ country house, Gardencourt (the snow is a detail added by the film). Goodwood makes his passionate appeal, and takes Isabel in his arms. She responds to his kiss, but then breaks away and runs back to the door of the house. She stops with her hand on the door, turns, and looks back at him. Freeze frame: end of film. Isabel’s expression and body language in the freeze frame are ambiguous. Is she turning back to Goodwood, deciding not to open the door that leads back to social respectability and emotional sterility? Or is she asserting that she is not running away at all, but courageously “affronting her destiny”? (This is James’s phrase in the Preface to the New Your edition of the novel, using “affront” in the slightly archaic sense of to confront defiantly.) It is impossible to tell. But this indeterminate conclusion is preferable to the screenplay’s sentimental ending. The Wings of the Dove was the best received of the recent James films. Stephen Holden in the New York Times, for instance, said: “Few films have explored the human face this searchingly and found such complex psychological topography. That’s shy The Wings of the Dove succeeds where virtually every other film translation of a James novel has stumbled…the English director [Iain Softley] has found the equivalent of James’s elaborately analytical prose in the shadow play of eagerness, suspicion and self-doubt flickering across the face of its troubled three main characters.” Holden put his finger on the fundamental challenge of adapting James for the cinema. Not all of his colleagues were as impressed as this, but the film did well at the box office, and was nominated for two Oscars—for Helena Bonham Carter’s performance as Kate Croy and for Hossein amini’s screenplay. This screenplay has been published, with a short but very interesting introduction by the writer. I happen to know that Amini was commissioned to write the screenplay after the film had been in development for several years, beginning with a script by the biographer and critic Claire Tomalin, which was much more faithful to the original novel. Amini (who had previously scripted Jude, a feature film adaptation of Hardy’s Jude the Obscure), describes his first impression of James’s novel as follows: …an extraordinary book, but very long, very dense, and completely uncinematic. The story telling was internal, the key scenes were all reported after the event, and each character took on the narrative in a baton structure. But Amini had always been a fan of film noir, the generic term given by French film theorists to certain Hollywood films of the 1940s that dealt with stories of illicit love and crime from the point of view of the transgressors—films like Mildred Pierce, The postman Always rings Twice, and Double Indemnity. In The Wings of the Dove he perceived a “film noir in costume” waiting to be made: “two lovers deceive and betray a friend and corrupt their love in the process. It was irresistible to a noir buff.” Amini candidly admits that “by reducing the novel to its basic story spine we risked losing much of the texture and complexity of the original, and there was a danger of drifting into melodrama.” But, he claims, this was the only was to make a film of James’s novel that would engage a modern mass audience. And he was to a large extent justified by the result. “Where the book plays the major confrontations ‘off camera,’” Amini says, “I had to reinvent them.” In fact most of the scenes in the film are either invented by Amini, or deviate significantly from the corresponding scenes in the novel. Some examples of invented scenes: Kate tracking her father to an opium den; Densher being denied access to Aunt Maud’s house; Kate and Milly giggling over pornographic illustrations in a bookshop; Milly’s first meeting with Densher at a party which he attends with another woman on his arm—a deliberate provocation to Kate; Kate visiting Densher at his newspaper office; Kate visiting Densher in his lodgings. Lord Mark is transformed into a drunken villain, and he blunders into Kate’s bedroom in the middle of the night, when she is his guest, to say that he intends to marry Milly for her money but really desires Kate. The whole Venice carnival sequence, in which Milly excites Kate’ jealousy by dancing with Densher, provoking Kate into letting Densher have sex with her standing up against a wall on the canalside, is, needless to say, invented—and incidentally is taking place at the wrong time of year.

Washington Square, though it should be the easiest of the three to adapt. It is a short novel with a very dramatic story and lots of good scenes, as its previous adaptations for the stage and then the screen (as The Heiress) had shown. Catherine, the plain daughter of the rich Dr Sloper, is courted by a shallow adventurer, Morris Townsend, abetted by her Aunt Lavinia, and steadfastly opposed by her dominating father. For some inscrutable reason the American producers cast two British actors, Albert Finney and Maggie Smith, for two of these four Americn characters, and employed a Polish director, Agnieszka Holland, to direct. As one would expect, Finney and Maggie Smith give excellent performances, but there were surely several American actors who would have done just as well. Maggie Smith’s character, Aunt Lavinia, has been made less interesting than in the novel, where her vicarious romantic infatuation with Townsend is largely responsible for the tragedy. In the novel she is mischievous, in the film merely comic or pathetic. There is an absurd and totally incredible scene in the film when she arranges to meet Townsend clandestinely in a low dive (it is an oyster bar in the novel) where a couple are actually having noisy sexual intercourse behind a thin, tattered curtain at her back as she talks to Townsend. Washington Squareand The Portrait of a Lady, in different ways, fall between two stools: trying to be faithful to a classic and trying to make a commercially successful movie for a modern audience. The Golden Bowl comes closest to squaring this circle.

|

|

| ( 知識學習|語言 ) |